The “Bollywoodization” of Popular Indian Visual Culture: a Critical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Art in Indian Context

Artistic Narration, Vol. IX, 2018, No. 2: ISSN (P) : 0976-7444 (e) : 2395-7247Impact Factor 6.133 (SJIF) Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Richa Singh Asso. Prof., Research Scholar Deptt. of Drawing & Painting M.F.A. M.M.H. College B.Ed. Ghaziabad, U.P. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Abstract: This article has a focus on Contemporary Art in Indian context. Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai Through this article emphasizesupon understanding the changes in Richa Singh, Contemporary Art over a period of time in India right from its evolution to the economic liberalization period than in 1990’s and finally in the Contemporary Art in current 21st century. The article also gives an insight into the various Indian Context, techniques and methods adopted by Indian Contemporary Artists over a period of time and how the different generations of artists adopted different techniques in different genres. Finally the article also gives an insight Artistic Narration 2018, into the current scenario of Indian Contemporary Art and the Vol. IX, No.2, pp.35-39 Contemporary Artists reach to the world economy over a period of time. key words: Contemporary Art, Contemporary Artists, Indian Art, 21st http://anubooks.com/ Century Art, Modern Day Art ?page_id=485 35 Contemporary Art in Indian Context Dr. Hemant Kumar Rai, Richa Singh Contemporary Art Contemporary Art refers to art – namely, painting, sculpture, photography, installation, performance and video art- produced today. Though seemingly simple, the details surrounding this definition are often a bit fuzzy, as different individuals’ interpretations of “today” may widely vary. -

The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama in John Osborne's

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (September. 2018) 77-80 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama In John Osborne’s “ Look Back In Anger” Sadaf Zaman Lecturer University of Bisha Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Sadaf Zaman ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission:16-09-2018 Date of acceptance: 01-10-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------- John Osborne was born in London, England in 1929 to Thomas Osborne, an advertisement writer, and Nellie Beatrice, a working class barmaid. His father died in 1941. Osborne used the proceeds from a life insurance settlement to send himself to Belmont College, a private boarding school. Osborne was expelled after only a few years for attacking the headmaster. He received a certificate of completion for his upper school work, but never attended a college or university. After returning home, Osborne worked several odd jobs before he found a niche in the theater. He began working with Anthony Creighton's provincial touring company where he was a stage hand, actor, and writer. Osborne co-wrote two plays -- The Devil Inside Him and Personal Enemy -- before writing and submittingLook Back in Anger for production. The play, written in a short period of only a few weeks, was summarily rejected by the agents and production companies to whom Osborne first submitted the play. It was eventually picked up by George Devine for production with his failing Royal Court Theater. Both Osborne and the Royal Court Theater were struggling to survive financially and both saw the production of Look Back in Anger as a risk. -

Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock

The Hitchcock 9 Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock Justin Mckinney Presented at the National Gallery of Art The Lodger (British Film Institute) and the American Film Institute Silver Theatre Alfred Hitchcock’s work in the British film industry during the silent film era has generally been overshadowed by his numerous Hollywood triumphs including Psycho (1960), Vertigo (1958), and Rebecca (1940). Part of the reason for the critical and public neglect of Hitchcock’s earliest works has been the generally poor quality of the surviving materials for these early films, ranging from Hitchcock’s directorial debut, The Pleasure Garden (1925), to his final silent film, Blackmail (1929). Due in part to the passage of over eighty years, and to the deterioration and frequent copying and duplication of prints, much of the surviving footage for these films has become damaged and offers only a dismal representation of what 1920s filmgoers would have experienced. In 2010, the British Film Institute (BFI) and the National Film Archive launched a unique restoration campaign called “Rescue the Hitchcock 9” that aimed to preserve and restore Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films — The Pleasure Garden (1925), The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), Easy Virtue (1927), The Ring (1927), Champagne (1928), The Farmer’s Wife (1928), The Manxman (1929), and Blackmail (1929) — to their former glory (sadly The Mountain Eagle of 1926 remains lost). The BFI called on the general public to donate money to fund the restoration project, which, at a projected cost of £2 million, would be the largest restoration project ever conducted by the organization. Thanks to public support and a $275,000 dona- tion from Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation in conjunction with The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the project was completed in 2012 to coincide with the London Olympics and Cultural Olympiad. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

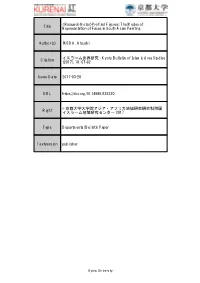

The Modes of Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting

<Research Notes>Profiled Figures: The Modes of Title Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting Author(s) IKEDA, Atsushi イスラーム世界研究 : Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies Citation (2017), 10: 67-82 Issue Date 2017-03-20 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/225230 ©京都大学大学院アジア・アフリカ地域研究研究科附属 Right イスラーム地域研究センター 2017 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University イスラーム世界研究 第 10 巻(2017 年 3 月)67‒82 頁 Profiled Figures Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies, 10 (March 2017), pp. 67–82 Profiled Figures: The Modes of Representation of Faces in South Asian Painting IKEDA Atsushi* Introduction This paper argues that South Asian people’s physical features such as eye and nose prompted Hindu painters to render figures in profile in the late medieval and early modern periods. In addition, I would like to explore the conceptual and theological meanings of each mode i.e. the three quarter face, the profile view, and the frontal view from both Islamic and Hindu perspectives in order to find out the reasons why Mughal painters adopted the profile as their artistic standard during the reign of Jahangīr (1605–27). Various facial modes characterized South Asian paintings at each period. Perhaps the most important example of paintings in South Asia dates from B.C. 1 to A.C. 5 century and is located in the Ajantā cave in India. It depicts Buddhist ascetics in frontal view, while other figures are depicted in three quarter face with their eyes contained within the line that forms the outer edge (Figure 1). Moving to the Ellora cave paintings executed between the 5th and 7th century, some figures show the eye in the far side pushed out of the facial line. -

EXIGENCY of INDIAN CINEMA in NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Culturalistic Design: Design Approach to Create Products

CULTURALISTIC DESIGN: DESIGN APPROACH TO CREATE PRODUCTS FOR SPECIFIC CULTURAL AND SUBCULTURAL GROUPS Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this thesis is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This thesis does not include proprietary or classified information. Brandon J. Allen Certificate of Approval: Bret Smith Tin Man Lau, Chair Professor Professor Industrial Design Industrial Design Tsai Lu Liu George T. Flowers Assistant Professor Dean Industrial Design Graduate School CULTURALISTIC DESIGN: DESIGN APPROACH TO CREATE PRODUCTS FOR SPECIFIC CULTURAL AND SUBCULTURAL GROUPS Brandon J. Allen A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Industrial Design Auburn, Alabama May 9, 2009 CULTURALISTIC DESIGN: DESIGN APPROACH TO CREATE PRODUCTS FOR SPECIFIC CULTURAL AND SUBCULTURAL GROUPS Brandon J. Allen Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. Signature of Author Date of Graduation iii THESIS ABSTRACT CULTURALISTIC DESIGN: DESIGN APPROACH TO CREATE PRODUCTS FOR SPECIFIC CULTURAL AND SUBCULTURAL GROUPS Brandon J. Allen Master of Industrial Design, May 9, 2009 (B.I.D., Auburn University, 2005) 93 Typed Pages Directed by Tin Man Lau Designers have a unique process for solving problems commonly referred to as design thinking. Design thinking, especially on a cultural level can be used to tackle a wide range of creative and business issues. Design thinking with true cultural infusion is known as “Culturalistic Design”, and can have profound and varying effects on product designs. -

Huq, Rupa. "Pastoral Paradises and Social Realism: Cinematic Representations of Suburban Complexity." Making Sense of Suburbia Through Popular Culture

Huq, Rupa. "Pastoral Paradises and Social Realism: Cinematic Representations of Suburban Complexity." Making Sense of Suburbia through Popular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. 83–108. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472544759.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 04:19 UTC. Copyright © Rupa Huq 2013. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 Pastoral Paradises and Social Realism: Cinematic Representations of Suburban Complexity I never wanted to get into this rat-race but now that I’m in it I think I’d be a fool not to play it just like everyone else plays it. (Gregory Peck as Tom Rath, Th e Man in the Gray Flannel Suit , 1956) Th e cinema in its literal sense has been both a landmark of the suburban-built environment and staple source of popular culture in the post-war era: with the Regals, Gaumonts, UCGs and ABCs off ering relatively cheap escapism from everyday mundanity and routine. Th e cinema has served the function of a venue for suburban courtship for couples and entertainment for fully formed family units with the power to move audiences to the edge of their seats in suspense or to tears – be that laughter or of sadness. While the VHS and advent of domestic video recorders was seen to threaten the very existence of the cinema, many suburban areas have seen the old high street picture palaces replaced/displaced/ succeeded by out-of-town complexes where suburbia has sometimes been the subject on the screen as well as the setting of the multiplex they are screened in. -

Carol Zemel, Looking Jewish: Visual Culture and Modern Diaspora, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015, 216 Pp. 72 B/W Illus

Document généré le 30 sept. 2021 02:25 RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne Canadian Art Review Carol Zemel, Looking Jewish: Visual Culture and Modern Diaspora, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015, 216 pp. 72 b/w illus. $ 45 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-253-01542-6 Nicholas Chare Volume 43, numéro 1, 2018 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050830ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1050830ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Association d'art des universités du Canada) ISSN 0315-9906 (imprimé) 1918-4778 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer ce compte rendu Chare, N. (2018). Compte rendu de [Carol Zemel, Looking Jewish: Visual Culture and Modern Diaspora, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015, 216 pp. 72 b/w illus. $ 45 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-253-01542-6]. RACAR : Revue d'art canadienne / Canadian Art Review, 43(1), 111–113. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050830ar Tous droits réservés © UAAC-AAUC (University Art Association of Canada | Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des Association d'art des universités du Canada), 2018 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ der bildenden Künste (1843). -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Indian Art History from Colonial Times to the R.N

The shaping of the disciplinary practice of art Parul Pandya Dhar is Associate Professor in history in the Indian context has been a the Department of History, University of Delhi, fascinating process and brings to the fore a and specializes in the history of ancient and range of viewpoints, issues, debates, and early medieval Indian architecture and methods. Changing perspectives and sculpture. For several years prior to this, she was teaching in the Department of History of approaches in academic writings on the visual Art at the National Museum Institute, New arts of ancient and medieval India form the Delhi. focus of this collection of insightful essays. Contributors A critical introduction to the historiography of Joachim K. Bautze Indian art sets the stage for and contextualizes Seema Bawa the different scholarly contributions on the Parul Pandya Dhar circumstances, individuals, initiatives, and M.K. Dhavalikar methods that have determined the course of Christian Luczanits Indian art history from colonial times to the R.N. Misra present. The spectrum of key art historical Ratan Parimoo concerns addressed in this volume include Himanshu Prabha Ray studies in form, style, textual interpretations, Gautam Sengupta iconography, symbolism, representation, S. Settar connoisseurship, artists, patrons, gendered Mandira Sharma readings, and the inter-relationships of art Upinder Singh history with archaeology, visual archives, and Kapila Vatsyayan history. Ursula Weekes Based on the papers presented at a Seminar, Front Cover: The Ashokan pillar and lion capital “Historiography of Indian Art: Emergent during excavations at Rampurva (Courtesy: Methodological Concerns,” organized by the Archaeological Survey of India). National Museum Institute, New Delhi, this book is enriched by the contributions of some scholars Back Cover: The “stream of paradise” (Nahr-i- who have played a seminal role in establishing Behisht), Fort of Delhi. -

Chapter Thirty Visual Culture/Visual Studies James D. He"Bert

Chapter Thirty Visual Culture/Visual Studies James D. He"bert "Visual culture" has emerged of late as a term meant to encom pass all h Ulnan products with a pronounced visual as pect-including those that do not, as a matter of social practice, carry the imprimatur of art. "Visual studies" (which I select from a number of cognate designations currently in use) serves as a convenient name for the academic discipline that takes visual cul ture as its object of study. The day has passed, however, when a nascent discipline such as visual studies can justify itself simply by gathering more goodies behind its disciplinary parapets: art ... and much more! Practical considerations aside (and such consid erations are far from trifling in the modern university), the exer cise smacks of unreasonable acquisitiveness, of academic hubris. Visual studies, rather than engaging in the science of accounting for a massive collection of fresh data points, must embark on the historical and social analysis of the hierarchies whose formation and operation have generated-and will continue to generate, even under the aegis of visual studies-greater interest in some artifacts than in others. To enlarge the compass of the study of vi sual artifacts beyond art does not force scholars to homogenize away the differences between art (or other favored categories) and things not thus endowed. Visual studies, rather than leveling all artifacts into the meaningless commonality of "the visuaL" treats the field of the visual as a place to examine the social mech"ni51115 of differentiation. Let me, then, offer an abbreviated sketch of the expanded tcr ritory-the necessarily and self-consciously artificial territory across which visual studies hopes to chart the production of hier archies among artifacts.