Screen1900 Schulze Diss Phal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXIGENCY of INDIAN CINEMA in NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

Raja Harishchandra Is a Most Thrilling Story from Indian Mythology. Harishchandra Was a Great King of India, Who Flourished Several Centuries Before the Christian Era

Notes The Times of India gave pre-screening publicity as follows: 'Raja Harishchandra is a most thrilling story from Indian mythology. Harishchandra was a great king of India, who flourished several centuries before the Christian era. He (sic) and his wife's names were household words in every Indian home for their truthfulness and chastity respectively. Their son Rohidas was a marvellous type of noble manhood. What Job was in Christian (sic) Bible, so Harischandra was in the Indian mythology. The patience of this king was tried so much that he was reduced to utter poverty and he had to pass his days in jungles in the company of cruel beasts. The same fate overcame his faithful wife and the dutiful son. But truth tri- umphed at last and they came out successfully through the ordeal. Several Indian scenes as depicted in this film are sim- ply marvellous. It is really a pleasure to see this piece of Indian workmanship'. The Bombay Chronicle, while reviewing Raja Harishchandra in its issue of Monday, 5th May 1913 said, 'An interesting de- parture is made this week by the management of Coronation Cinematographer. The first great Indian dramatic film on the lines of the great epics of the western world ... it is curious that the first experiment in this direction was so long in com- ing (sic) ... all the stories of Indian mythology era will long make their appearance ... followed by representations of modern dramas and comedies, another field which opens up vast possibilities ... it is to Mr Phalke that Bombay owes this .. -

A Delightful Panchatantra Polonium, Named After Blowing for Nicole and I

HINDUSTAN TIMES, NEW DELHI 04 hindustantimes FRIDAY, APRIL 21, 2017 ht kaleidoscope thisdaythatera S W I M M I N G LEGEND CURIES ISOLATE YOUR SHOT RADIUM Might make a comeback if I get the itch, says Phelps Michael Phelps hasn’t gotten the urge to return to swimming. Not yet anyway. THE WINNINGEST ATHLETE IN The winningest athlete in Olympic history is OLYMPIC HISTORY IS CLEARLY clearly enjoying marriage, fatherhood and a ENJOYING MARRIAGE, FATHERHOOD newfound willingness to speak out on conten- tious issues such as doping. AND A NEWFOUND WILLINGNESS TO n Marie Curie But, in a tantalising concession that he hasn’t SPEAK OUT ON CONTENTIOUS totally closed the door on another comeback, n On April 20, 1902, Marie and Phelps said that it might be tough to stay away ISSUES SUCH AS DOPING. Pierre Curie isolated from the pool - especially if he attends the world BUT PHELPS SAID HE HASN’T radioactive radium from the championships in Budapest, Hungary, in July. mineral pitchblende in their “The true test will be, if I do end up going over TOTALLY CLOSED THE DOOR ON laboratory in Paris. In 1898, to the worlds this summer, do I have that itch the Curies discovered the ANOTHER COMEBACK again?” Phelps said Tuesday during a telephone existence of radium and interview. more. This is a really cool opportunity for me to polonium in pitchblende. They shared the 1903 Nobel He was already strongly considering his first do some things I was not able to do when I was Prize in physics with French comeback when he attended the 2013 champion- swimming.” scientist A Henri Becquerel ships in Barcelona, and there was no doubt he’d That includes lending his still-considerable for work on radioactivity. -

Travel Log #1: an Ode to the City of Death (Varanasi; November-December 2019) Alexander Mark Kinaj

Travel Log #1: An Ode to the City of Death (Varanasi; November-December 2019) Alexander Mark Kinaj Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: American journeys to India with the hope of finding peace, enlightenment, nirvana—whatever you’d like to call it. Ostensibly, not a novel plan, I know. But this wasn’t my first time in India, so I was already self-aware about the Sisyphean nature of my aspirations. That is, searching for something that could be found in my backyard of upstate New York—and really, within myself—yet trekking back to India each time a new existential crisis cropped up. I was also self-aware of another potential pitfall: namely, using travel as a means of escaping my problems or fears, rather than confronting them. However, after my first trip to India back in 2016, I realized traveling, real traveling, brought you closer to your fears and really, yourself. I think one of my favorite authors, James Baldwin, summed it up best when he said, “I met a lot of people in Europe. I even encountered myself.” When I arrived in Delhi on November 1st, beleaguered from a 24-hour journey that included a layover in Russia, I was greeted by a familiar, albeit grown, face: Sparsh. It had been four years since I had seen the cousin of my highschool classmate, Monica, and he had grown as much as one can from 13 to 17. He was the only child of the Dutt family, and we became very close during the short amount of time I spent in Delhi. -

The Influence of Raja Ravi Varma's Mythological Subjects in Popular

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2016 The nflueI nce of Raja Ravi Varma’s Mythological Subjects in Popular Art Rachel Cooksey SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Graphic Design Commons Recommended Citation Cooksey, Rachel, "The nflueI nce of Raja Ravi Varma’s Mythological Subjects in Popular Art" (2016). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2511. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2511 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Influence of Raja Ravi Varma’s Mythological Subjects in Popular Art Rachel Cooksey India: National Identity & the Arts December 9th, 2016 Cooksey 2 Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………….…. 3 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….… 4 Dedication………………………………………………………………………………….……. 5 The Power of Images …………….. …………………………………………………….………. 6 Ravi Varma and His Influences…..……………………………………………………….………9 Ravi Varma’s Style …..…………………………………………………………………….……13 The Shift from Paintings to Prints…………………..………………………………………….. 17 Other Artists……….………………………………………………………………….………… -

The Survival of Hindu Cremation Myths and Rituals

THE SURVIVAL OF HINDU CREMATION MYTHS AND RITUALS IN 21ST CENTURY PRACTICE: THREE CONTEMPORARY CASE STUDIES by Aditi G. Samarth APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Riccio, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Richard Brettell, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Melia Belli-Bose ___________________________________________ Dr. David A. Patterson ___________________________________________ Dr. Mark Rosen Copyright 2018 Aditi G. Samarth All Rights Reserved Dedicated to my parents, Charu and Girish Samarth, my husband, Raj Shimpi, my sons, Rishi Shimpi and Rishabh Shimpi, and my beloved dogs, Chowder, Haiku, Happy, and Maya for their loving support. THE SURVIVAL OF HINDU CREMATION MYTHS AND RITUALS IN 21ST CENTURY PRACTICE: THREE CONTEMPORARY CASE STUDIES by ADITI G. SAMARTH, BFA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank members of Hindu communities across the globe, and specifically in Bali, Mauritius, and Dallas for sharing their knowledge of rituals and community. My deepest gratitude to Wayan at Villa Puri Ayu in Sanur, Bali, to Dr. Uma Bhowon and Professor Rajen Suntoo at the University of Mauritius, to Pandit Oumashanker, Pandita Barran, and Pandit Dhawdall in Mauritius, to Mr. Paresh Patel and Mr. Ashokbhai Patel at BAPS Temple in Irving, to Pandit Janakbhai Shukla and Pandit Harshvardhan Shukla at the DFW Hindu Ekta Mandir, and to Ms. Stephanie Hughes at Hughes Family Tribute Center in Dallas, for representing their varied communities in this scholarly endeavor, for lending voice to the Hindu community members they interface with in their personal, professional, and social spheres, and for enabling my research and documentation during a vulnerable rite of passage. -

English Language and Literature Core Course VIII – Film Studies

English Language and Literature SEMESTER V Core Course VIII – Film Studies (EN 1543) Part 2 FILM MOVEMENTS SOVIET MONTAGE (1924-1930) • Montage is a technique in film editing in which a series of shorts are edited into a sequence to compact space, time, and information. • Visual montage may combine shots to tell a story chronologically or may juxtapose images to produce an impression or to illustrate an association of ideas. • Montage technique developed early in cinema, primarily through the work of the American directors Edwin S. Porter and D.W. Griffith. Soviet Montage • Soviet Montage Montage describes cutting together images that aren’t in spatial or temporal continuity. • Director Lev Kulshov first conceptualized montage theory on the basis that one frame may not be enough to convey an idea or an emotion • •The audience are able to view two separate images and subconsciously give them a collective context. • In the 1920s, a lack of film stock meant that Soviet filmmakers often re-edited existing films or learned how to make films by deconstructing old ones rather than shooting new material. • When they did shoot film, they often had only short lengths of film left over from other productions, so they not only used short shots, they often planned them in great detail. Kuleshov Effect • Kuleshov experiment is a good example. • The basic notion that a subsequent image could affect the viewer’s interpretation of the previous one was supported by behavioral psychology theories popular at the time. • Kuleshov concluded from his experiment that editing created the opportunity to link entirely unrelated material in the minds of the viewers, who were no longer seen as simply absorbing meaning from the images, but actually creating meaning by associating the different images and drawing meaning from their juxtaposition. -

The “Bollywoodization” of Popular Indian Visual Culture: a Critical Perspective

tripleC 12(1): 277-285, 2014 http://www.triple-c.at The “Bollywoodization” of Popular Indian Visual Culture: A Critical Perspective Keval J. Kumar Adjunct Professor, Mudra Institute of Communications, Ahmedabad, India. kevalku- [email protected] Abstract: The roots of popular visual culture of contemporary India can be traced to the mythological films produced by D. G. Phalke during the decades of the ‘silent’ era from 1912 to 1934. The era of the “talkies” of the 1930s ushered in the “singing’” or musical genre, which together with Phalke’s visual style remains the hallmark of Bollywood cinema. The history of Indian cinema is replete with films made in other genres and styles (e. g., social realism, satires, comedies, fantasy, horror, or stunt) in the numerous languages of the country. However, it is the popular Hindi cinema (now generally termed Bollywood) that has dominated national Indian cinema and its audiovisual culture. It has hegemonized the entire film industry as well as other popular technology-based art forms including the press, radio, television, music, advertising, the worldwide web, the social media, and telecommunica- tions media. The form and substance of these modern art forms, while adapting to the demands of the new media technologies, continued to be rooted in the visual arts and practices of folk and classical traditions of earlier times. Keywords: Visual Culture, Hegemony, Visual Style, Indian Cinema, Indian Television, Indian Advertising 1. Introduction Infinite diversity, plurality and multiplicity are the primary features that mark popular Indian visual culture. This culture has come about through centuries of absorption, integration and acculturation, as the subcontinent evolved at its own leisurely pace engaging with invaders, settlers and colonialists who brought with them audio and visual cultures of their own. -

SAGA of BIRTH of FIRST INDIAN MOVIE Dadasaheb

SAGA OF BIRTH OF FIRST INDIAN MOVIE Dadasaheb returned from London. A convenient and spa- cious place was necessary for the filming of movies. He be- gan a search for it. By then, Laxmi Printing Art Works had shifted from Mathuradas Makanji's Mathura Bhavan to Sankli Street at Byculla, so that his bungalow at Dadar was vacant. While in Mumbai, Dadasaheb had lived in this bun- galow for seven years. He now called on Mathuradasseth, who was glad that a painstaking, imaginative artist like Dadasaheb wished to start a new venture in his bungalow. He handed it over to Dadasaheb who then shifted his family from Ismail Building at Charni Road to this bungalow. This birthplace of Indian Film Industy still stands at Dadasaheb Phalke Road, Dadar, with the name 'Mathura Bhavan'. The subject for a movie was already under consideration. In his magazine Suvarnamala, Dadasaheb had already written a story, 'Surabaichi Kahani', depicting the ill effects of drinking. Before selecting the story, Dadasaheb saw the American movies screened in Mumbai such as Singomar, Protect, etc. in order to get a proper idea of the type of movies which the audiences like. He found that movies based on mystery and love were patronised by Europeans, Parsis and people in the lower strata of society. So, if a movie is to be public-oriented, its subject should be such as would appeal to the middle class people and women, so that they would see it in large numbers, and it should also highlight Indian culture. SAGA OF BIRTH OF FIRST INDIAN MOVIE Dadasaheb knew well that cultural and religious feel- ings were rooted deep in the heart. -

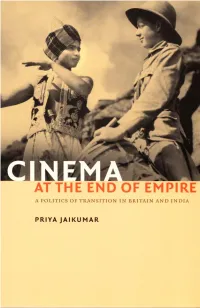

Cinema at the End of Empire: a Politics of Transition

cinema at the end of empire CINEMA AT duke university press * Durham and London * 2006 priya jaikumar THE END OF EMPIRE A Politics of Transition in Britain and India © 2006 Duke University Press * All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Quadraat by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data and permissions information appear on the last printed page of this book. For my parents malati and jaikumar * * As we look back at the cultural archive, we begin to reread it not univocally but contrapuntally, with a simultaneous awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts. —Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism CONTENTS List of Illustrations xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1. Film Policy and Film Aesthetics as Cultural Archives 13 part one * imperial governmentality 2. Acts of Transition: The British Cinematograph Films Acts of 1927 and 1938 41 3. Empire and Embarrassment: Colonial Forms of Knowledge about Cinema 65 part two * imperial redemption 4. Realism and Empire 107 5. Romance and Empire 135 6. Modernism and Empire 165 part three * colonial autonomy 7. Historical Romances and Modernist Myths in Indian Cinema 195 Notes 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Films 309 General Index 313 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Reproduction of ‘‘Following the E.M.B.’s Lead,’’ The Bioscope Service Supplement (11 August 1927) 24 2. ‘‘Of cource [sic] it is unjust, but what can we do before the authority.’’ Intertitles from Ghulami nu Patan (Agarwal, 1931) 32 3. -

![The Vedic-Aryan Entry Into Contemporary Nepal [A Pre-Historical Analysis Based on the Study of Puranas]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3032/the-vedic-aryan-entry-into-contemporary-nepal-a-pre-historical-analysis-based-on-the-study-of-puranas-4313032.webp)

The Vedic-Aryan Entry Into Contemporary Nepal [A Pre-Historical Analysis Based on the Study of Puranas]

The Vedic-Aryan Entry Into Contemporary Nepal [A Pre-Historical Analysis Based on the Study Of Puranas] - Shiva Raj Shrestha "Malla' [Very little is known about pre-historical Nepal, Kumauni Brahmans (after I, 100 A.D.) were the first ils people and Aryan entry into Nepal. A hazy picture Aryans to enter Nepal and settle down. But there are of Aryan invasion of Nepal and the contemporary some very clear indications that the Pre-Vedic and aborigines people of Nepal can be drawn with the Vedic Aryans had already entered Nepal much help of Sata-Patha Brahman records and various earlier.] Puranas. In these mythological records one can also The Back-Drop find sufficient details about Yakshays, Kinnars and Some 3, 500 to 4,000 years "Before Present' Naga-Kiratas and Indo-austroloids like Nishadhas. (B.P.) Hari-Hara Chhetra (of present day Gandaki By the middle of 20th century, many scholars had Basins, including Mukti Nath, Deaughat andTriveni realized that original versions of Puranas contain of Western Nepal), was one of the most important historical oral traditionsof thousandsofyears. Famous centers of Vedic Aryans, who had already expanded scholars and historians like Pargiter, Kirfel, K.P. Swarswat Vedic Civilization. Just before this time, Jaiswal and Dr. Satya Ketu Vidyalankar etc. have Raja Harishchandra was ruling northern India, from very firmly opined that on the basis of Puranas an his capital of Ayodhya in those days. Raja Dasharata outline of Vedic Aryan civilization and its clash with (Lord Rama's father) was born in the famous Raghu Harappa Sindha civilization (Hari-Upa according to dynasty after some 29 generations from King Rig-Veda) can be drawn. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. The Aesthetics of Emotional Acting: An Argument for a Rasa-based Criticism of Indian Cinema and Television PIYUSH ROY PhD South Asian Studies The University of Edinburgh 2016 1 DECLARATION This thesis has been composed by me and is my own work. It has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Piyush Roy 25 February 2017 2 For Thakuba (Aditya Prasanna Madhual), Aai (Malatilata Rout), Julki apa and Pramila Panda aunty II संप्रेषण का कोई भी माध्यम कला है और संप्रेषण का संदेश ज्ञान है. जब संदेश का उद्येश्य उत्तेजना उत्पन करता हो तब कला के उस 셂प को हीन कहते हℂ. जब संदेश ननश्वार्थ प्रेम, सत्य और महान चररत्र की रचना करता हो, तब वह कला पनवत्र मानी जाती है II ननदेशक चंद्रप्रकाश निवेदी, उपननषद् गंगा, एप.