A History of Juvenile Justice Policy in Texas – Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAP Crystal Reports

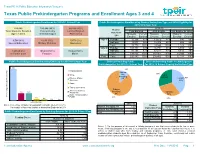

Texas PK-16 Public Education Information Resource Texas Public Prekindergarten Programs and Enrollment Ages 3 and 4 Public Prekindergarten Enrollment for 2015-16 School Year Public Prekindergarten Enrollment by Student Instruction Type and ADA Eligibility for 2015-16 School Year 220,640 190,848 (86%) 88,295 (40%) 2015-16 Student Total Students Enrolled Economically Limited English Total Enrolled ADA Eligible Not Eligible for ADA Instruction Ages 3 and 4 Disadvantaged Proficiency Type Students Percent Students Percent Students Percent Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled 8,594 (4%) 6,611 (3%) 5,471 (2%) Age 3 Full-day 12,206 47% 11,616 47% 590 50% Special Education Military Children Homeless Half-day 13,573 53% 12,974 53% 599 50% Total 25,779 100% 24,590 100% 1,189 100% Age 4 Full-day 103,380 53% 96,791 53% 6,589 60% 1,695 (0.8%) 109,816 (50%) 110,824 (50%) Half-day 91,481 47% 87,071 47% 4,410 40% In Foster Care Females Males Total 194,861 100% 183,862 100% 10,999 100% Total Total 220,640 100% 208,452 100% 12,188 100% Public Prekindergarten Enrollment by Ethnicity for 2015-16 School Year Districts Providing Public Districts Providing Public Prekindergarten Prekindergarten for 2015-16 School Year for 2015-16 School Year by Instruction Type 64% 13% Hispanic/Latino Districts 30% White Not Full & Providing Half-day 40% Black or African PK Full-Day American Only Asian Two or more races Districts American Indian or Providing 15% 15% Alaska Nat Half-Day PK Native Hawaiian/Other Only Percentage of Students Enrolled Students of -

Texas Youth Commission (TYC) and Transferred All Functions, Duties and Responsibilities of These Former Agencies to TJJD

Comprehensive Report Youth Reentry and Reintegration December 1, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................... 1 ASSESSMENTS ............................................................................................................................ 1 PROGRAMS ................................................................................................................................ 2 NETWORK OF TRANSITION PROGRAMS .................................................................................... 5 IDENTIFICATION OF LOCAL PROVIDERS AND TRANSITIONAL SERVICES .................................... 7 Children’s Aftercare Reentry Experience (CARE) ................................................................ 9 Gang Intervention Treatment: Reentry Development for Youth (GitRedy) ....................... 9 SHARING OF INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 10 OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................................. 10 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................ 14 APPENDICES .............................................................................................................................. -

The Texas Youth Commission

JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE OPERATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE TEXAS YOUTH COMMISSION PRELIMINARY REPORT OF INITIAL FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS A REPORT TO THE LT. GOVERNOR AND THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE 80TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE JOHN WHITMIRE JERRY MADDEN SENATE CO-CHAIRMAN HOUSE CO-CHAIRMAN Joint Select Committee on the Operation and Management of the Texas Youth Commission Preliminary Report of Initial Findings and Recommendations Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Preliminary Report III. Proclamation IV. Attachment One - Recommended Action Plan by Committee V. Attachment Two - Statistical Breakdown by TDCJ-OIG VI. Attachment Three - Filed Legislation VII. Attachment Four - State Auditor's Report 07-022 VIII. Attachment Five - McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility - Case File Review EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The Texas Youth Commission (TYC) is the state agency responsible for the care, custody and rehabilitation of the juvenile offenders who have been committed by the court. The ages of youth committed to TYC ranges from 10 to 17. The TYC can maintain custody of the youth until the age of twenty-one (21). Allegations of mistreatment, disturbances and abuse began to surface and the TYC came under federal scrutiny due to the riot at the Evins Regional Juvenile Center in Edinburg, Texas. The U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, began an investigation at the Evins facility in September 2006 and issued their report on March 15, 2007, stating "certain conditions at Evins violate the constitutional rights of the youth". The Senate Criminal Justice Committee, the House Corrections Committee and the Juvenile Justice and Family Issues Committee conducted separate public hearings allowing staff, youth, family members, child advocacy groups, the ACLU and other concerned citizens to be heard. -

Texas Education Agency Overview

Texas Education Agency Overview 100 - Office of the Commissioner; Senior Policy Advisor The Commissioner's Office provides leadership to schools, manages the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and provides coordination with the state legislature and other branches of state government as well as the U. S. Department of Education. SBOE activities and rules, commissioner rules and regulations, commissioner hearing decisions, coordinates with state legislature, Commissioner’s Correspondence and Complaints Management. Number of FTEs: 6 Correspondence Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to correspondence received by members of the public, local education agencies (LEAs), legislature, and other state agencies. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 03-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function serves as a review and distribution center for correspondence assigned to other offices in coordination with Complaints Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. Complaints Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to complaints received by members of the public. Through various activities, this function ensures that the operations of the Agency’s complaint system is compliant with applicable regulations and policy and effectively meets identified needs of the Agency. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 04-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function mainly serves as a review and distribution center for complaints assigned to other offices in coordination with Correspondence Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. -

Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS

STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS Report to the Governor October 2009 Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR OCTOBER 2009 TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE JERRY PATTERSON, COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION SB 1262 Summary Texas Natural Resources Code, Chapter 31, Subchapter E, [Senate Bill 1262, 74th Texas Legislature, 1995] amended two years of previous law related to the reporting and disposition of state agency land. The amendments established a more streamlined process for disposing of unused or underused agency land by defining a reporting and review sequence between the Land Commissioner and the Governor. Under this process, the Asset Management Division of the General Land Office provides the Governor with a list of state agency properties that have been identified as unused or underused and a set of recommended real estate transactions. The Governor has 90 days to approve or disapprove the recommendations, after which time the Land Commissioner is authorized to conduct the approved transactions. The statute freezes the ability of land-owning state agencies to change the use or dispose of properties that have recommended transactions, from the time the list is provided to the Governor to a date two years after the recommendation is approved by the Governor. Agencies have the opportunity to submit to the Governor development plans for the future use of the property within 60 days of the listing date, for the purpose of providing information on which to base a decision regarding the recommendations. The General Land Office may deduct expenses from transaction proceeds. -

20-21 Proposed Budget Narrative

FISCAL YEAR 2021 (2020-2021) PROPOSED BUDGET & PLAN OF MUNICIPAL SERVICES JULY 30, 2020 Declarations required by the State of Texas: This budget will raise more revenue from property taxes than last year’s budget by $84,818.16 (3.5 percent) and of that amount $28,997.08 is tax revenue to be raised from new property added to the tax roll this year. The City of Gatesville proposes to use the increase in the total tax revenue for the purpose of equipment for the additional School Resource Officers and new equipment for the Street Department. This notification statement complies with Texas Local Government Code § 102.005 This budget raises more property tax revenue compared to the previous year’s budget. The Gatesville City Council adopted the budget with the following voting record: City Council Ward 1, Place 1: Vacant City Council Ward 1, Place 2: Randy Hitt City Council Ward 1, Place 3/Mayor Pro-Tem: Meredith Rainer City Council Ward 2, Place 4: William Robinette City Council Ward 2, Place 5: Greg Casey City Council Ward 2, Place 6: Jack Doyle Ordinance 2020-___, dated September __, 2020 This notification statement complies with Texas Local Government Code § 102.007 Information regarding the City’s property tax rate follows: Fiscal Year 2020 (preceding): $0.5600/$100 valuation Fiscal Year 2021 (current): TBD/$100 valuation Fiscal Year 2021: Adopted Rate: $0.TBD/$100 valuation No-New-Revenue Tax Rate: $0.5509/$100 valuation No-New-Revenue Maintenance and Operations Tax Rate: $0.583/$100 valuation Voter Approval Tax Rate: $0.6588/$100 valuation Debt Tax Rate: $0.2399/$100 valuation De Minimis Rate: $0.7602/$100 valuation Total Debt Obligations Secured by Property Taxes: $961,017 CITY MANAGER July 30, 2020 The Honorable Mayor Gary Chumley, Mayor Pro Tem Rainer, and Members of the City Council, I am pleased to submit the proposed budget for Fiscal Year 2021 which begins on October 1, 2020 and ends on September 30, 2021. -

Of the Reformatory Inmate Tory at Cheshire, Conn

+~++++++1'+11!~ -~- ~*********~+ + NOVEMBER 1914 + ~ ~ t T E CHRON CLE ; + + r A Monthly journal devoWd Edited by and Published in :!: ~ to the Spirit of Reform and to the Interest of the Inmates ~ + the Onward and Upward Lift of the Connecticut Refonna- + + of the Reformatory Inmate tory at Cheshire, Conn. + ~ + + + + + -.~r .... ~. ' . ,( > v · SPECIAL NUMBER DEDICATED TO THE WELFARE OF THE MEN ON PAROLE FU -4 1916 GREETINGS The Chronicle believes that the Press, as a moulder of public opin ion, can be, if so utilized, the great est force for good in the world. In accord with its belief, a copy of this issue is being mailed to every news paper of importance in the State of Connecticut. mqr <t!f1rnnirlr DEVOTED TO THE BEST INTERESTS OF THE REFORMATORY, "WITH MALICE TOWARD NONE AND CHARITY FOR ALL." VoL. I CHESHIRE, CONN., NOVEMBER 1, 1914 No.lO OPPORTUNITY ~ ~~~~;?,~!~.uE,.~~~!:!;!!. DIFFERENT VIEWS OF WHAT THE REFORMATORY OFFERS I of the Reformatory-especially the membe1·s of the I teachmg force--are requested to read the followittg in BY AN OPTIMIST BY THE EDITOR I the sincere hope that theymoybenefit thereby.--Editor) HE COURT sentences you to the Co'1necticut Re· A YEAR is but a period of time by which man mea- A MAN may resolve and decide to put aside evil T furmatory, where it is hoped you may learn by its sures his life. As our year here draws to a close and to lead a better life; he mc.y exhort, preach. advantages to turn from a poor beginning to a life of we can not help but think v. -

Comparison of Colorado, Texas and Missouri Juvenile Rehabilitation

COMPARISON OF COLODARO TEXAS AND MISSOURI JUVENILE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS SUMMER 2004 Colorado, Texas and Missouri all claim to have exemplary youth correctional facilities in regards to the successful rehabilitation of severe youth offenders. A comparison of the three systems shows that there are similarities between the facilities, but there are also key differences. These key differences help define the different programs from each other, as well as their performance and success rates. This report looks at how the facilities operate, the operating costs, how the youth get placed there, who the youth typically are, and the recidivism rates of the different programs in comparison to the costs. FACILITIES AND OPERATIONS] To understand the difference in performance among the three states one must understand the different ways the state facilities operate. One of the main differences between the three states’ programs, deals with the specific department jurisdiction of the rehabilitation program. COLORADO YOUTH OFFENDER SERVICES In Colorado the YOS program is operated by the adult correctional commission know as the Colorado Department of Corrections. The YOS program is only open to those youth who are adjudicated as adults and then meet the offense standards. Currently if a juvenile commits a class one felony or specific class two felonies, they are not eligible for the Colorado YOS program, and carry out their sentence in the adult prison system. Kids who do enter the YOS system go through 4 phases. First, offenders are admitted to the IDO or the Intake, Diagnostic and Orientation Program where they spend the first 30 days learning how the entire program works, and developing certain behavioral skills similar to a basic training regiment of the armed services. -

Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas

JuvenilesJuveniles inin thethe AdultAdult CriminalCriminal JusticeJustice SystemSystem inin TexasTexas by Michele Deitch Special Project Report Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas By Project Director Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc., Senior Lecturer LBJ School of Public Affairs Student Participants Emily Ling, LBJ School of Public Affairs Emma Quintero, University of Texas School of Law Suggested citation for this report: Michele Deitch (2011). Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas, Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, LBJ School of Public Affairs A Special Project Report from the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin Applied Research in Juvenile and Criminal Justice—Fall Semester 2010 March 2011 © 2011 by The University of Texas at Austin All rights reserved. Cover design by Doug Marshall, LBJ School Communications Office Cover photo by Steve Liss/The AmericanPoverty.org Campaign TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary x Part I: Introduction 1 A. Purpose of Report 1 B. Methodology 2 C. Structure of Report 2 Part II: Overview 3 A. Historical Background 3 B. Sentencing and Transfer Options for Serious Juvenile Offenders Under Texas Law 4 C. Problems with Confining Juveniles in Adult Prisons and Jails 6 Part III: Findings 9 A. Numbers of adult certification cases vs. juvenile determinate sentencing 9 B. Characteristics of certified and determinate sentence populations 10 (1) Demographics 10 Age 10 Gender 11 Ethnicity 12 County of Conviction 12 (2) Criminal Offense 13 (3) Criminal History 16 Prior Referrals to Juvenile Court 17 Prior Referrals to Juvenile Court for Violent Offenses 17 Prior TYC Commitments 18 C. -

Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio History Faculty Publications College of Arts and Sciences 2004 Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas William S. Bush Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/hist_faculty Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Copyright by William Sebastian Bush 2004 The Dissertation Committee for William Sebastian Bush Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas Committee: Mark C. Smith, Supervisor Janet Davis Julia Mickenberg King Davis Sheldon Ekland-Olson Representing the Juvenile Delinquent: Reform, Social Science, and Teenage Troubles in Postwar Texas by William Sebastian Bush, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2004 Dedication For Mary and Alexander Acknowledgements Researching and writing a dissertation tests the emotions as well as the intellect. The two become so closely intertwined that scholarly advice invariably doubles as a salve for personal anxieties. Whether they knew it or not, practically everyone mentioned below bolstered my ever-flagging confidence even as they talked out ideas or problems that seemed bound within the more detached constraints of a dissertation project. Others just listened patiently to barely coherent thesis ideas, anxious brainstorming outbursts, and the usual angry tirades against academia. -

Juvenile Justice Reform in Texas: the Onc Text, Content & Consequences of Senate Bill 1630 Sara A

Journal of Legislation Volume 42 | Issue 2 Article 5 5-27-2016 Juvenile Justice Reform in Texas: The onC text, Content & Consequences of Senate Bill 1630 Sara A. Gordon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Family Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Sara A. Gordon, Juvenile Justice Reform in Texas: The Context, Content & Consequences of Senate Bill 1630, 42 J. Legis. 232 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg/vol42/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journal of Legislation at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Legislation by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUVENILE JUSTICE REFORM IN TEXAS: THE CONTEXT, CONTENT & CONSEQUENCES OF SENATE BILL 1630 Sara A. Gordon* INTRODUCTION In 2003, Jimmy Martinez, a resident of San Antonio, entered the Texas criminal justice system after missing his school bus.1 Charged with truancy and destruction of property, Jimmy was sent to live in a county juvenile detention center for six months.2 Five months into his sentence, he was transferred to a secure state facility four hun- dred miles from his home and managed by the Texas Youth Commission (hereinafter TYC) (now the Texas Juvenile Justice Department).3 While a prisoner of that facil- ity, Jimmy witnessed his best friend’s murder and was regularly -

Towards a Public History of the Ohio State Reformatory Veronica Bagley University of Akron, [email protected]

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Spring 2018 Towards a Public History of the Ohio State Reformatory Veronica Bagley University of Akron, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Bagley, Veronica, "Towards a Public History of the Ohio State Reformatory" (2018). Honors Research Projects. 750. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/750 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Towards a Public History of the Ohio State Reformatory Veronica Bagley The University of Akron Honors Thesis Spring 2018 Bagley 2 Abstract This Honors Project is a combination of a written Honors Thesis and my own work for The Ohio State Reformatory Historic Site (OSRHS), and is being submitted to The University of Akron in pursuit of an undergraduate degree in history. I completed archival work for my internship at OSRHS as a part of my Certificate in Museum and Archive Studies.