Summary of Legislative Budget Board Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAP Crystal Reports

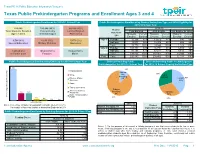

Texas PK-16 Public Education Information Resource Texas Public Prekindergarten Programs and Enrollment Ages 3 and 4 Public Prekindergarten Enrollment for 2015-16 School Year Public Prekindergarten Enrollment by Student Instruction Type and ADA Eligibility for 2015-16 School Year 220,640 190,848 (86%) 88,295 (40%) 2015-16 Student Total Students Enrolled Economically Limited English Total Enrolled ADA Eligible Not Eligible for ADA Instruction Ages 3 and 4 Disadvantaged Proficiency Type Students Percent Students Percent Students Percent Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled Enrolled 8,594 (4%) 6,611 (3%) 5,471 (2%) Age 3 Full-day 12,206 47% 11,616 47% 590 50% Special Education Military Children Homeless Half-day 13,573 53% 12,974 53% 599 50% Total 25,779 100% 24,590 100% 1,189 100% Age 4 Full-day 103,380 53% 96,791 53% 6,589 60% 1,695 (0.8%) 109,816 (50%) 110,824 (50%) Half-day 91,481 47% 87,071 47% 4,410 40% In Foster Care Females Males Total 194,861 100% 183,862 100% 10,999 100% Total Total 220,640 100% 208,452 100% 12,188 100% Public Prekindergarten Enrollment by Ethnicity for 2015-16 School Year Districts Providing Public Districts Providing Public Prekindergarten Prekindergarten for 2015-16 School Year for 2015-16 School Year by Instruction Type 64% 13% Hispanic/Latino Districts 30% White Not Full & Providing Half-day 40% Black or African PK Full-Day American Only Asian Two or more races Districts American Indian or Providing 15% 15% Alaska Nat Half-Day PK Native Hawaiian/Other Only Percentage of Students Enrolled Students of -

Texas Youth Commission (TYC) and Transferred All Functions, Duties and Responsibilities of These Former Agencies to TJJD

Comprehensive Report Youth Reentry and Reintegration December 1, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................................... 1 ASSESSMENTS ............................................................................................................................ 1 PROGRAMS ................................................................................................................................ 2 NETWORK OF TRANSITION PROGRAMS .................................................................................... 5 IDENTIFICATION OF LOCAL PROVIDERS AND TRANSITIONAL SERVICES .................................... 7 Children’s Aftercare Reentry Experience (CARE) ................................................................ 9 Gang Intervention Treatment: Reentry Development for Youth (GitRedy) ....................... 9 SHARING OF INFORMATION .................................................................................................... 10 OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................................. 10 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................ 14 APPENDICES .............................................................................................................................. -

The Texas Youth Commission

JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE OPERATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE TEXAS YOUTH COMMISSION PRELIMINARY REPORT OF INITIAL FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS A REPORT TO THE LT. GOVERNOR AND THE SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE 80TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE JOHN WHITMIRE JERRY MADDEN SENATE CO-CHAIRMAN HOUSE CO-CHAIRMAN Joint Select Committee on the Operation and Management of the Texas Youth Commission Preliminary Report of Initial Findings and Recommendations Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Preliminary Report III. Proclamation IV. Attachment One - Recommended Action Plan by Committee V. Attachment Two - Statistical Breakdown by TDCJ-OIG VI. Attachment Three - Filed Legislation VII. Attachment Four - State Auditor's Report 07-022 VIII. Attachment Five - McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility - Case File Review EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The Texas Youth Commission (TYC) is the state agency responsible for the care, custody and rehabilitation of the juvenile offenders who have been committed by the court. The ages of youth committed to TYC ranges from 10 to 17. The TYC can maintain custody of the youth until the age of twenty-one (21). Allegations of mistreatment, disturbances and abuse began to surface and the TYC came under federal scrutiny due to the riot at the Evins Regional Juvenile Center in Edinburg, Texas. The U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, began an investigation at the Evins facility in September 2006 and issued their report on March 15, 2007, stating "certain conditions at Evins violate the constitutional rights of the youth". The Senate Criminal Justice Committee, the House Corrections Committee and the Juvenile Justice and Family Issues Committee conducted separate public hearings allowing staff, youth, family members, child advocacy groups, the ACLU and other concerned citizens to be heard. -

Texas Education Agency Overview

Texas Education Agency Overview 100 - Office of the Commissioner; Senior Policy Advisor The Commissioner's Office provides leadership to schools, manages the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and provides coordination with the state legislature and other branches of state government as well as the U. S. Department of Education. SBOE activities and rules, commissioner rules and regulations, commissioner hearing decisions, coordinates with state legislature, Commissioner’s Correspondence and Complaints Management. Number of FTEs: 6 Correspondence Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to correspondence received by members of the public, local education agencies (LEAs), legislature, and other state agencies. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 03-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function serves as a review and distribution center for correspondence assigned to other offices in coordination with Complaints Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. Complaints Management Function Description: This function serves to oversee, coordinate, and conduct activities associated with managing and responding to complaints received by members of the public. Through various activities, this function ensures that the operations of the Agency’s complaint system is compliant with applicable regulations and policy and effectively meets identified needs of the Agency. This function operates under the authority of Agency OP 04-01, for which the Office of the Commissioner is the Primary Office of Responsibility (OPR). This function mainly serves as a review and distribution center for complaints assigned to other offices in coordination with Correspondence Management and the Public Information Coordination Office. -

Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS

STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS Report to the Governor October 2009 Jerry Patterson, Commissioner Texas General Land Office General Land Office Texas STATE AGENCY PROPERTY RECOMMENDED TRANSACTIONS REPORT TO THE GOVERNOR OCTOBER 2009 TEXAS GENERAL LAND OFFICE JERRY PATTERSON, COMMISSIONER INTRODUCTION SB 1262 Summary Texas Natural Resources Code, Chapter 31, Subchapter E, [Senate Bill 1262, 74th Texas Legislature, 1995] amended two years of previous law related to the reporting and disposition of state agency land. The amendments established a more streamlined process for disposing of unused or underused agency land by defining a reporting and review sequence between the Land Commissioner and the Governor. Under this process, the Asset Management Division of the General Land Office provides the Governor with a list of state agency properties that have been identified as unused or underused and a set of recommended real estate transactions. The Governor has 90 days to approve or disapprove the recommendations, after which time the Land Commissioner is authorized to conduct the approved transactions. The statute freezes the ability of land-owning state agencies to change the use or dispose of properties that have recommended transactions, from the time the list is provided to the Governor to a date two years after the recommendation is approved by the Governor. Agencies have the opportunity to submit to the Governor development plans for the future use of the property within 60 days of the listing date, for the purpose of providing information on which to base a decision regarding the recommendations. The General Land Office may deduct expenses from transaction proceeds. -

Comparison of Colorado, Texas and Missouri Juvenile Rehabilitation

COMPARISON OF COLODARO TEXAS AND MISSOURI JUVENILE REHABILITATION PROGRAMS SUMMER 2004 Colorado, Texas and Missouri all claim to have exemplary youth correctional facilities in regards to the successful rehabilitation of severe youth offenders. A comparison of the three systems shows that there are similarities between the facilities, but there are also key differences. These key differences help define the different programs from each other, as well as their performance and success rates. This report looks at how the facilities operate, the operating costs, how the youth get placed there, who the youth typically are, and the recidivism rates of the different programs in comparison to the costs. FACILITIES AND OPERATIONS] To understand the difference in performance among the three states one must understand the different ways the state facilities operate. One of the main differences between the three states’ programs, deals with the specific department jurisdiction of the rehabilitation program. COLORADO YOUTH OFFENDER SERVICES In Colorado the YOS program is operated by the adult correctional commission know as the Colorado Department of Corrections. The YOS program is only open to those youth who are adjudicated as adults and then meet the offense standards. Currently if a juvenile commits a class one felony or specific class two felonies, they are not eligible for the Colorado YOS program, and carry out their sentence in the adult prison system. Kids who do enter the YOS system go through 4 phases. First, offenders are admitted to the IDO or the Intake, Diagnostic and Orientation Program where they spend the first 30 days learning how the entire program works, and developing certain behavioral skills similar to a basic training regiment of the armed services. -

Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas

JuvenilesJuveniles inin thethe AdultAdult CriminalCriminal JusticeJustice SystemSystem inin TexasTexas by Michele Deitch Special Project Report Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas By Project Director Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc., Senior Lecturer LBJ School of Public Affairs Student Participants Emily Ling, LBJ School of Public Affairs Emma Quintero, University of Texas School of Law Suggested citation for this report: Michele Deitch (2011). Juveniles in the Adult Criminal Justice System in Texas, Austin, TX: The University of Texas at Austin, LBJ School of Public Affairs A Special Project Report from the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin Applied Research in Juvenile and Criminal Justice—Fall Semester 2010 March 2011 © 2011 by The University of Texas at Austin All rights reserved. Cover design by Doug Marshall, LBJ School Communications Office Cover photo by Steve Liss/The AmericanPoverty.org Campaign TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures v Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary x Part I: Introduction 1 A. Purpose of Report 1 B. Methodology 2 C. Structure of Report 2 Part II: Overview 3 A. Historical Background 3 B. Sentencing and Transfer Options for Serious Juvenile Offenders Under Texas Law 4 C. Problems with Confining Juveniles in Adult Prisons and Jails 6 Part III: Findings 9 A. Numbers of adult certification cases vs. juvenile determinate sentencing 9 B. Characteristics of certified and determinate sentence populations 10 (1) Demographics 10 Age 10 Gender 11 Ethnicity 12 County of Conviction 12 (2) Criminal Offense 13 (3) Criminal History 16 Prior Referrals to Juvenile Court 17 Prior Referrals to Juvenile Court for Violent Offenses 17 Prior TYC Commitments 18 C. -

Chapter 10. Texas Dispositional Alternatives Danny Pirtile Introduction Juvenile Judges and District Attorneys Play an Important

Chapter 10. Texas Dispositional Alternatives Danny Pirtile Introduction Juvenile judges and district attorneys play an important role in determining appropriate and often-necessary sanctions for those youth deemed delinquent and incorrigible. In the late 1980s, there was a transitional period for the juvenile justice system, where state legislatures began to institute policies aimed at violent, serious, and chronic juvenile offenders (Snyder & Sickmund, 1995; TJPC, 2003). Texas was not immune to the dramatic policy shifts being initiated during the late 1980s and early 1990s that was due to an overwhelming increase in juvenile crime and public fear of habitual and violent youthful offenders. Cox, Conrad, Allen and Hanser (2007) present a plethora of programs and dispositional choices available to juvenile justice officials. This chapter presents dispositional programs available to Texas juvenile officials and the milieu of these dispositions. Texas lawmakers developed policies that sought to decrease the non-adversarial nature of the juvenile court and replace them with increased procedural similarities to the adult criminal justice system. These legislative changes resulted in the creation of laws that significantly altered dispositions or adjudicatory outcomes in the juvenile justice system. Juvenile judges and prosecutors received increased authority and were provided with a wide range of dispositional alternatives which included placing a youth on probation to transferring the case to the adult system. Thus, the new goal was to focus more on providing tougher, offense based sanctions, while still retaining some of the safeguards provided in the juvenile justice system, which ultimately rely on the parens patriae doctrine of rehabilitation and focus on the best interests of the child. -

Juvenile Justice Reform in Texas: the Onc Text, Content & Consequences of Senate Bill 1630 Sara A

Journal of Legislation Volume 42 | Issue 2 Article 5 5-27-2016 Juvenile Justice Reform in Texas: The onC text, Content & Consequences of Senate Bill 1630 Sara A. Gordon Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Family Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Juvenile Law Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Sara A. Gordon, Juvenile Justice Reform in Texas: The Context, Content & Consequences of Senate Bill 1630, 42 J. Legis. 232 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg/vol42/iss2/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journal of Legislation at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Legislation by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUVENILE JUSTICE REFORM IN TEXAS: THE CONTEXT, CONTENT & CONSEQUENCES OF SENATE BILL 1630 Sara A. Gordon* INTRODUCTION In 2003, Jimmy Martinez, a resident of San Antonio, entered the Texas criminal justice system after missing his school bus.1 Charged with truancy and destruction of property, Jimmy was sent to live in a county juvenile detention center for six months.2 Five months into his sentence, he was transferred to a secure state facility four hun- dred miles from his home and managed by the Texas Youth Commission (hereinafter TYC) (now the Texas Juvenile Justice Department).3 While a prisoner of that facil- ity, Jimmy witnessed his best friend’s murder and was regularly -

UNT-0020-0177.Pdf

TxD Y200.6 J826 95/09 i1OCUMEN!TSW0 :VTRV 95-28JAN0. i9; Texas Youth Commission September 1995, Fall Issue 4900 N. Lamar, Austin, TX 78765 News and Information from throughout the Agency Lindgren resigns; Briscoe named acting de puty director In this issue: ay Lindgren, Deputy Executive Direc- Lindgren's duties in Rhode Island will tor of the Youth Ccommission since include responsibility for youth correction Marlin 'Reception January 15, 1988, as resigned to ac- juvenile probation, pretrial detention, men- cept the position of Director of the Rhode tal health services for children, and child Center' opens Island Department of Children, Youth and protective services. His appointment was Story on page 7. Families, effective August 15. made by Rhode Island Governor Lincoln Executive Director Steve Robinson ap- Almond. pointed Judy Briscoe, TYC's Director of "It has been an honor to serve on what Outstanding 1995 Delinquency Prevention, as acting deputy I am certain is the best juvenile corrections director. Employees Honored (rontinuedd o"rpage ) Stories and photospages 11-16. IN THIS ISSUE Legislation.................................. 3 Annual Workshop.........................11 Construction Contract .................. 15 RIF Policy......................................23 New Administrators.................23 m SanctionSancion Unit......25nit.................................2 Former TYC Board Member Lary York, center was honored when the TYC halfway house in Corpus Christi was renamed York House. Also pictured are current Board Chairman Gary D. Project RIO....................................26 Compton ofAmarillo, left, and State Senator John Montford ofLubbock; keynote speaker SECTIONS Halfway house renamed to Around TYC ............................... 3 honor former Board Member Volunteers ............. 18 e Corpus Christi halfway house, formerly called Nueces House for the county in Youth g ........................ -

Understanding and Addressing Youth Violence in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department

UNDERSTANDING AND ADDRESSING YOUTH VIOLENCE IN THE TEXAS JUVENILE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT Report to the Office of the Independent Ombudsman by Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc. Amy Madore Kate Vickery Alycia Welch SPECIAL PROJECT REPORT Understanding and Addressing Youth Violence in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department Report to the Office of the Independent Ombudsman by Project Director Michele Deitch, J.D., M.Sc. Senior Lecturer, LBJ School of Public Affairs LBJ School Student Participants Amy Madore Kate Vickery Alycia Welch Special Project Report Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 ISBN: 978-89940-924-5 © 2013 by the University of Texas at Austin All rights reserved. Table of Contents Acknowledgements vii Executive Summmary ix List of Findings xix List of Tables and Figures xxv Chapter I: Introduction 1 A. Origins of the Report 1 B. Purpose of the Report 2 C. Methodology 2 D. Structure of the Report 4 Chapter II: Background 7 A. TYC Crisis of 2007 7 B. Reform Efforts Since 2007 8 (1) Senate Bill 103 8 (2) Reduction in Population and Closure of Facilities 9 (3) Shift Towards Treatment-Oriented Approach 10 C. Major Operational Changes and Challenges at TYC 11 (1) Use of Force and Use of Pepper Spray 11 (2) Staffing Shortages 11 (3) Sexual Assault Allegations 12 D. Creation of Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) 12 E. Recent Reports about Violence in TJJD 13 v Understanding and Addressing Youth Violence in the Texas Juvenile Justice Department Chapter III: A Profile of Violence in TJJD’s Secure Facilities 15 A. -

Process Evaluation of the Texas Youth Commission's Chemical, Dependency Treatment Program*

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Process Evaluation of the Texas Youth Commission’s Chemical Dependency Treatment Program – Final Report Author(s): William R. Kelly Document No.: 182367 Date Received: May 15, 2000 Award Number: 97-RT-VX-K016 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. A PROCESS EVALUATION OF THE TEXAS YOUTH COMMISSION'S CHEMICAL, DEPENDENCY TREATMENT PROGRAM* Final Report Submitted to: National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs U.S. Department of Justice Submitted b)): Dr. William R. Kelly, Principal Investigator March 29,2000 *Direct correspondence to Dr. William R. Kelly (Principal Investigator), Professor and Director, Center for Criminology and Criminal Justice Research, University of Texas at Austin, Burdine 336, Austin, Texas 78712-1088, phone (512-471-1 122), fax (512-471-1748), e-mail ([email protected]). This research was supported by a National Institute of Justice research grant (#97-RT-VX-KO 16). Data were provided by the Texas Youth Commission. The Principal Investigator alone is responsible for all analyses and interpretations provided herein. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice.