Contributions to the Mosquito Fauna of Southeast Asia II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mosquito Species Identification Using Convolutional Neural Networks With

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Mosquito species identifcation using convolutional neural networks with a multitiered ensemble model for novel species detection Adam Goodwin1,2*, Sanket Padmanabhan1,2, Sanchit Hira2,3, Margaret Glancey1,2, Monet Slinowsky2, Rakhil Immidisetti2,3, Laura Scavo2, Jewell Brey2, Bala Murali Manoghar Sai Sudhakar1, Tristan Ford1,2, Collyn Heier2, Yvonne‑Marie Linton4,5,6, David B. Pecor4,5,6, Laura Caicedo‑Quiroga4,5,6 & Soumyadipta Acharya2* With over 3500 mosquito species described, accurate species identifcation of the few implicated in disease transmission is critical to mosquito borne disease mitigation. Yet this task is hindered by limited global taxonomic expertise and specimen damage consistent across common capture methods. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are promising with limited sets of species, but image database requirements restrict practical implementation. Using an image database of 2696 specimens from 67 mosquito species, we address the practical open‑set problem with a detection algorithm for novel species. Closed‑set classifcation of 16 known species achieved 97.04 ± 0.87% accuracy independently, and 89.07 ± 5.58% when cascaded with novelty detection. Closed‑set classifcation of 39 species produces a macro F1‑score of 86.07 ± 1.81%. This demonstrates an accurate, scalable, and practical computer vision solution to identify wild‑caught mosquitoes for implementation in biosurveillance and targeted vector control programs, without the need for extensive image database development for each new target region. Mosquitoes are one of the deadliest animals in the world, infecting between 250–500 million people every year with a wide range of fatal or debilitating diseases, including malaria, dengue, chikungunya, Zika and West Nile Virus1. -

Data-Driven Identification of Potential Zika Virus Vectors Michelle V Evans1,2*, Tad a Dallas1,3, Barbara a Han4, Courtney C Murdock1,2,5,6,7,8, John M Drake1,2,8

RESEARCH ARTICLE Data-driven identification of potential Zika virus vectors Michelle V Evans1,2*, Tad A Dallas1,3, Barbara A Han4, Courtney C Murdock1,2,5,6,7,8, John M Drake1,2,8 1Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 2Center for the Ecology of Infectious Diseases, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 3Department of Environmental Science and Policy, University of California-Davis, Davis, United States; 4Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, United States; 5Department of Infectious Disease, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 6Center for Tropical Emerging Global Diseases, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 7Center for Vaccines and Immunology, University of Georgia, Athens, United States; 8River Basin Center, University of Georgia, Athens, United States Abstract Zika is an emerging virus whose rapid spread is of great public health concern. Knowledge about transmission remains incomplete, especially concerning potential transmission in geographic areas in which it has not yet been introduced. To identify unknown vectors of Zika, we developed a data-driven model linking vector species and the Zika virus via vector-virus trait combinations that confer a propensity toward associations in an ecological network connecting flaviviruses and their mosquito vectors. Our model predicts that thirty-five species may be able to transmit the virus, seven of which are found in the continental United States, including Culex quinquefasciatus and Cx. pipiens. We suggest that empirical studies prioritize these species to confirm predictions of vector competence, enabling the correct identification of populations at risk for transmission within the United States. *For correspondence: mvevans@ DOI: 10.7554/eLife.22053.001 uga.edu Competing interests: The authors declare that no competing interests exist. -

The Introduction of Toxorhynchites Brevipalpis Theobald Into the Purpose of This Brief Paper Is to Place on Record an Account Of

Vol. XIV, No. 2, March, 1951 237 The Introduction of Toxorhynchites brevipalpis Theobald into the Territory of Hawaii By DAVID D. BONNET MEDICAL ENTOMOLOGIST, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, HONOLULU and STEPHEN M. K. HU CHIEF, BUREAU OF MOSQUITO CONTROL, HONOLULU The purpose of this brief paper is to place on record an account of the introduction of the South African mosquito Toxorhynchites (= Megarhinus) * brevipalpis Theobald into the Territory of Hawaii. The importation of this insect and its establishment would, it is believed, aid in the control of the forest day mosquito, Aedes albopictus Skuse. Any type of container, whether it be a natural container such as a tree hole, bamboo stump, pineapple lily (Bilbergia sp.) or rock hole; or an artificial container such as a vine bowl, tin can, tub, auto tire or bottle, when filled with water, can serve as a breeding location for Aedes albopictus. This varied breeding habit complicates control as it neces sitates the treatment or elimination of a multitude of large and small water-holding containers. Adequate control has been obtained in the urban areas of Hawaii by premises-to-premises inspection, and house holder cooperation, following usual Aedes aegypti (L.) control pro cedures. There are, however, large areas outside the cities where such control measures are not feasible. These areas are principally mountain forest regions which contain a sufficient number of natural breeding situations to maintain a large mosquito population. This population of Aedes albopictus serves not only as a health menace and as a reservoir for reinvasion, but also discourages extensive use of many fine recreation areas. -

Cezzial ...Of Anophezes

Mosquito Systematics Vol. 18(l) 1986 THE MOSQUITO FAUNA OF THE RYUKYU ARCHIPELAGO WITH IDENTIFICATION KEYS, PUPAL DESCRIPTIONS AND NOTES ON BIOLOGY, MEDICAL IMPORTANCE AND DISTRIBUTION* TAKAKO TOMA AND ICHIRO MIYAGI** CONTENTS Abstract. ...................................................... Introduction. ................................................... Place and method. .............................................. Morphology and terminology. .................................... Keys to genera of Culicidae in the Ryukyu Archipelago. ......... Keys to subgenera of AnopheZes. ............................. ..l 1 Keys to species of AnopheZes (CeZZiaL ........................ 11 Keys to species of AnopheZes (AnopheZesl. ................... ..ll Keys to species of Toxorhynchites. .......................... ..lZ Keys to subgenera of Uranotaenia. ........................... ..13 Keys to species of Uranotaenia Wranotaenial. ............... ..13 Keys to species of Uranotaenia (PseudoficaZbial. ............ ..13 Keys to species of CoquCZZettidia. .......................... ..I 4 Keys to species of Mmomyia (BtorZeptiomyiaL ............... ..15 Keys to subgenera of Aedes. ................................. ..15 Keys to species of Aedes (FinZayaL ......................... ..I 7 Keys to species of Aedes (VerraZZinaL ...................... ..18 Keys to species of Aedes (StegomyiaL ....................... ..18 2 Keys to subgenera of CuZex. .................................. .1g Key to species of CuZex hhtziaL ............................. 21 Keys to -

A Checklist of Mosquitoes (Diptera: Pondicherrx India with Notes On

Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, ZO(3):22g_232,2004 Copyright @ 20M by the American Mosquito Control Association, Inc. A CHECKLIST OF MOSQUITOES (DIPTERA: CULICIDAE) OF PONDICHERRX INDIA WITH NOTES ON NEW AREA RECORDS A. R. RAJAVEL, R. NATARAJAN AND K. VAIDYANATHAN Vector Control Research Centre (ICMR), pondicherry 6O5 0O6, India ABSTRACT A checklist of mosquito species for Pondicherry, India, is presented based on collections made from November 1995 to September 1997. Mosquitoes of 64 species were found belonging to 23 subgenera and 14 genera, Aedeomyia, Aedes, Anopheles, Armigeres, Coquitlettidia, Culex, Ficalbia,- Malaya, Maisonia, Mi- momyia, Ochlerotatus, Toxorhynchites, {lranotaenia, and Verrallina. We report 25 new speciLs for pondicherry. KEY WORDS Mosquitoes, check list, new area records, pondicherry, India INTRODUCTION season. The period from December to February is Documentation of species is a critically impor- relatively cool. tant component of biodiversity studies and has great significance in conservation of genetic re- MATERIALS AND METHODS sources as well as control of pests and vectors. In India, mosquito fauna of several states has been Mosquito surveys were made from November documented, but comprehensive information on 1995 to September 1997 . Each of the 6 communes, species diversity is not available for Pondicherry. Ariankuppam, Bahour, Mannadipet, Nettapakkam, A recent update on the distribution of Aedini mos- Ozhukarai, and Villianur, were considered as dis- quitoes in India by Kaur (2003) included all the tinct units to ensure complete coverage of the re- states except Pondicheny. The 14 species of mos- gion, and collections were made in a total of 97 quitoes collected by Nair (1960) during the filarial villages among these and in the old town of Pon- survey in Pondicherry settlement is the earliest dicherry. -

Spongeweed-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Are Highly Effective

Environ Sci Pollut Res (2016) 23:16671–16685 DOI 10.1007/s11356-016-6832-9 RESEARCH ARTICLE Eco-friendly drugs from the marine environment: spongeweed-synthesized silver nanoparticles are highly effective on Plasmodium falciparum and its vector Anopheles stephensi, with little non-target effects on predatory copepods Kadarkarai Murugan1,2 & Chellasamy Panneerselvam3 & Jayapal Subramaniam1 & Pari Madhiyazhagan1 & Jiang-Shiou Hwang4 & Lan Wang5 & Devakumar Dinesh1 & Udaiyan Suresh1 & Mathath Roni1 & Akon Higuchi6 & Marcello Nicoletti7 & Giovanni Benelli8,9 Received: 13 April 2016 /Accepted: 4 May 2016 /Published online: 16 May 2016 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2016 Abstract Mosquitoes act as vectors of devastating pathogens (EDX), and X-ray diffraction (XRD). In mosquitocidal assays, and parasites, representing a key threat for millions of humans the 50 % lethal concentration (LC50)ofC. tomentosum extract and animals worldwide. The control of mosquito-borne dis- against Anopheles stephensi ranged from 255.1 (larva I) to eases is facing a number of crucial challenges, including the 487.1 ppm (pupa). LC50 of C. tomentosum-synthesized emergence of artemisinin and chloroquine resistance in AgNP ranged from 18.1 (larva I) to 40.7 ppm (pupa). In lab- Plasmodium parasites, as well as the presence of mosquito oratory, the predation efficiency of Mesocyclops aspericornis vectors resistant to synthetic and microbial pesticides. copepods against A. stephensi larvae was 81, 65, 17, and 9 % Therefore, eco-friendly tools are urgently required. Here, a (I, II, III, and IV instar, respectively). In AgNP contaminated synergic approach relying to nanotechnologies and biological environment, predation was not affected; 83, 66, 19, and 11 % control strategies is proposed. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Oral Presentation Abstracts ............................................................................................................................... 3 Plenary Session ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Adult Control I ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Mosquito Lightning Symposium ...................................................................................................................... 5 Student Paper Competition I .......................................................................................................................... 9 Post Regulatory approval SIT adoption ......................................................................................................... 10 16th Arthropod Vector Highlights Symposium ................................................................................................ 11 Adult Control II .......................................................................................................................................... 11 Management .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Student Paper Competition II ...................................................................................................................... 17 Trustee/Commissioner -

A Review of the Mosquito Species (Diptera: Culicidae) of Bangladesh Seth R

Irish et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:559 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1848-z RESEARCH Open Access A review of the mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) of Bangladesh Seth R. Irish1*, Hasan Mohammad Al-Amin2, Mohammad Shafiul Alam2 and Ralph E. Harbach3 Abstract Background: Diseases caused by mosquito-borne pathogens remain an important source of morbidity and mortality in Bangladesh. To better control the vectors that transmit the agents of disease, and hence the diseases they cause, and to appreciate the diversity of the family Culicidae, it is important to have an up-to-date list of the species present in the country. Original records were collected from a literature review to compile a list of the species recorded in Bangladesh. Results: Records for 123 species were collected, although some species had only a single record. This is an increase of ten species over the most recent complete list, compiled nearly 30 years ago. Collection records of three additional species are included here: Anopheles pseudowillmori, Armigeres malayi and Mimomyia luzonensis. Conclusions: While this work constitutes the most complete list of mosquito species collected in Bangladesh, further work is needed to refine this list and understand the distributions of those species within the country. Improved morphological and molecular methods of identification will allow the refinement of this list in years to come. Keywords: Species list, Mosquitoes, Bangladesh, Culicidae Background separation of Pakistan and India in 1947, Aslamkhan [11] Several diseases in Bangladesh are caused by mosquito- published checklists for mosquito species, indicating which borne pathogens. Malaria remains an important cause of were found in East Pakistan (Bangladesh). -

Diptera: Culicidae) in Southern Iran Accepted: 07-02-2017

International Journal of Mosquito Research 2017; 4(2): 27-38 ISSN: 2348-5906 CODEN: IJMRK2 IJMR 2017; 4(2): 27-38 Larval habitats, affinity and diversity indices of © 2017 IJMR Received: 06-01-2017 Culicinae (Diptera: Culicidae) in southern Iran Accepted: 07-02-2017 Ahmad-Ali Hanafi-Bojd Ahmad-Ali Hanafi-Bojd, Moussa Soleimani-Ahmadi, Sara Doosti and Department of Medical Entomology and Vector Control, Shahyad Azari-Hamidian School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Abstract Tehran, Iran. An investigation was carried out studying the ecology of the larvae of Culicinae (Diptera: Culicidae) in Moussa Soleimani-Ahmadi Bashagard County, Hormozgan Province, southern Iran. Larval habitat characteristics were recorded Social Determinants in Health according to habitat situation and type, vegetation, sunlight situation, substrate type, turbidity and water Promotion Research Center, depth during 2009–2011. Physicochemical parameters of larval habitat waters were analyzed for Hormozgan University of electrical conductivity (µS/cm), total alkalinity (mg/l), turbidity (NTU), total dissolved solids (mg/l), Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, total hardness (mg/l), acidity (pH), water temperature (°C) and ions such as calcium, chloride, Iran. magnesium and sulphate. In total, 1479 third- and fourth-instar larvae including twelve species representing four genera were collected and identified: Aedes vexans, Culex arbieeni, Cx. Sara Doosti bitaeniorhynchus, Cx. mimeticus, Cx. perexiguus, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx. sinaiticus, Cx. theileri, Cx. Department of Medical tritaeniorhynchus, Culiseta longiareolata, Ochlerotatus caballus and Oc. caspius. All species, except Cx. Entomology and Vector Control, bitaeniorhynchus, were reported for the first time in Bashagard County. Culiseta longiareolata (37.5%), School of Public Health, Tehran Cx. -

MS V18 N2 P199-214.Pdf

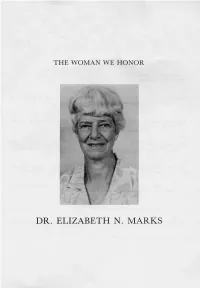

Mosquito Systematics Vol. 18(2) 1986 199 Biography of Elizabeth Nesta Marks Elizabeth Marks was born in Dublin, Ireland, on 28th April 1918 and was christened in St. Patrick's Cathedral (with which a parson ancestor had been associated), hence her nick-name Patricia or Pat. Her father, an engineering graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, had worked as a geologist in Queensland before returning to Dublin to complete his medical course. In 1920 her parents took her to their home town, Brisbane, where her father practiced as an eye specialist. Although an only child, she grew up in a closely knit family of uncles, aunts and cousins. Her grandfather retired in 1920 in Camp Mountain near Samford, 14 miles west of Brisbane, to a property known as "the farm" though most of it was under natural forest. She early developed a love of and interest in the bush. Saturday afternoons often involved outings with the Queensland Naturalists' Club (QNC), Easters were spent at QNC camps, Sundays and long holidays at the farm. Her mother was a keen horsewoman and Pat was given her first pony when she was five. She saved up five pounds to buy her second pony, whose sixth generation descendant is her present mount. In 1971 she inherited part of the farm, with an old holiday house, and has lived there since 1982. Primary schooling at St. John's Cathedral Day School, close to home, was followed by four years boarding at the Glennie Memorial School, Toowoomba, of which she was Dux in 1934. It was there that her interest in zoology began to crystallize. -

MOSQUITOES of the SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES

L f ^-l R A R > ^l^ ■'■mx^ • DEC2 2 59SO , A Handbook of tnV MOSQUITOES of the SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES W. V. King G. H. Bradley Carroll N. Smith and W. C. MeDuffle Agriculture Handbook No. 173 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE \ I PRECAUTIONS WITH INSECTICIDES All insecticides are potentially hazardous to fish or other aqpiatic organisms, wildlife, domestic ani- mals, and man. The dosages needed for mosquito control are generally lower than for most other insect control, but caution should be exercised in their application. Do not apply amounts in excess of the dosage recommended for each specific use. In applying even small amounts of oil-insecticide sprays to water, consider that wind and wave action may shift the film with consequent damage to aquatic life at another location. Heavy applications of insec- ticides to ground areas such as in pretreatment situa- tions, may cause harm to fish and wildlife in streams, ponds, and lakes during runoff due to heavy rains. Avoid contamination of pastures and livestock with insecticides in order to prevent residues in meat and milk. Operators should avoid repeated or prolonged contact of insecticides with the skin. Insecticide con- centrates may be particularly hazardous. Wash off any insecticide spilled on the skin using soap and water. If any is spilled on clothing, change imme- diately. Store insecticides in a safe place out of reach of children or animals. Dispose of empty insecticide containers. Always read and observe instructions and precautions given on the label of the product. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Agriculture Handbook No. -

The Role of Landmarks in Territory

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2014 The Role of Landmarks in Territory Maintenance by the Black Saddlebags Dragonfly, Tramea lacerata Jeffrey Lojewski Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Biological Sciences at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Lojewski, Jeffrey, "The Role of Landmarks in Territory Maintenance by the Black Saddlebags Dragonfly, Tramea lacerata" (2014). Masters Theses. 1305. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1305 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thesis Reproduction Certificate Page 1of1 THESIS MAINTENANCE AND REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses An important part of Booth Library at Eastern Illinois University's ongoing mission is to preserve and provide access to works of scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all theses produced at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. By signing this form: • You confirm your authorship of the thesis. • You retain the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis .