Women As Law School Students Beth L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

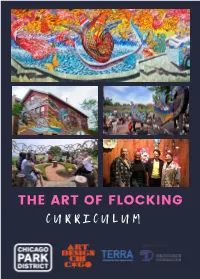

THE ART of FLOCKING CURRICULUM the Art of Flocking Curriculum

THE ART OF FLOCKING CURRICULUM The Art of Flocking Curriculum “There is an art to flocking: staying close enough not to crowd each other, aligned enough to maintain a shared direction, and cohesive enough to always move towards each other.” - adrienne maree brown The Art of Flocking: Cultural Stewardship in the Parks is a celebration of Chicago’s community-based art practices co-facilitated by the Chicago Park District and the Terra Foundation for American Art. A proud member of Art Design Chicago, this initiative aims to uplift Chicago artists with deep commitments to social justice, cultural preservation, community solidarity, and structural transformation. Throughout the summer of 2018, The Art of Flocking engaged 2,500 youth and families through 215 public programs and community exhibitions exploring the histories and legacies of Mexican-American public artist Hector Duarte and Sapphire and Crystals, Chicago's first and longest-standing Black women's artist collective.The Art of Flocking featured two beloved Chicago Park District programs: ArtSeed, designed to engage children ages 3 and up as well as their families and caretakers in 18 parks and playgrounds; and Young Cultural Stewards a multimedia youth fellowship centering young people ages 12–14 with regional hubs across the North, West, and South sides of Chicago. ArtSeed: Mobile Creative Play ArtSeed engages over 2,000 youth (ages 3-12) across 18 parks through storytelling, music, movement, and nature play rooted in neighborhood stories. Children explore the histories and legacies of Chicago's community-based artists and imagine creative solutions to challenges in their own neighborhoods. Teaching artists engage practice of social emotional learning, foundations in social justice, and trauma-informed pedagogy to cultivate children and families invested in fostering the cultural practices and creative capital of their parks and communities. -

37<? /V/ £ /D V3^5" the AGOLMIRTH CONSPIRACY DISSERTATION

37<? /v/ £ /d V3^5" THE AGOLMIRTH CONSPIRACY DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By James Cary Elston, B.A., B.B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas December, 1996 37<? /v/ £ /d V3^5" THE AGOLMIRTH CONSPIRACY DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By James Cary Elston, B.A., B.B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas December, 1996 Elston, James C. The Agolmirth Conspiracy. Doctor of Philosophy (English), December, 1996, 506 pages. Written in the tradition of the classic spy novels of Ian Fleming and the detective novels of Raymond Chandler, The Agolmirth Conspiracy represents the return to the thriller of its traditional elements of romanticism, humanism, fast-moving action, and taut suspense, and a move away from its cynicism and dehumanization as currently practiced by authors such as John Le Carre' and Tom Clancy. Stanford Torrance, an ex-cop raised on "old-fashioned" notions of uncompromising good and naked evil and largely ignorant of computer systems and high-tech ordinance, finds himself lost in a "modern" world of shadowy operatives, hidden agendas, and numerous double-crosses. He is nevertheless able to triumph over that world when he puts his own honor, his own dignity, and his very life on the line, proving to himself and to his adversaries that such things can still make things easier to see amid today's swirling moral fog. -

Making Music and Enriching Lives: a Guide for All Music Teachers

Blanchard Music | Education $24.95 “Beginning and experienced teachers will find new tricks and inspiration here to rekindle their love of teaching and music. Bonnie’s tips and stories will show how to run a photo by yuen lui studios, inc. studio, motivate students, deal with stage fright, teach artistry, and involve the whole family in music. This book M MAKING is serious about music, but it’s also fun—something that should always be part of good music instruction.” A —Sir James Galway KIN and “The Music for Life series stands alone as an incredible re- MUSIC source for all professional musicians—whether performing G or teaching. Music for Life deserves a standing ovation!” —Gerard Schwarz, Conductor, Seattle Symphony MUSIC Bonnie Blanchard ENRICHING “Bonnie Blanchard shares the teaching tricks that have worked so well in her own studio to produce successful students who are energized about their lessons and their music. Ms. Blanchard’s entertaining style makes this series a thoroughly enjoyable read.” LIVES —Bradley Garner, Professor of Flute, University of Cincinnati A College, Conservatory of Music, and Pre-Collegiate Faculty, ND Juilliard School A GUIDE FOR ALL MUSIC TEACHERS ENRICHIN Making Music and Enriching Lives is unlike any other in- Bonnie Blanchard structional book in the way it addresses comprehensive issues that affect all teachers, students, and musicians. In this book, with you will find specifics not only about how to teach music, but Cynthia Blanchard Acree also about how to motivate and inspire students of any age. Blanchard shares successful approaches with both students and teachers that have worked wonders in her own studio to produce successful students who are energized about their G INDIANA lessons and their music. -

8 Grade Science at Home Learning Packet

8th Grade Science At Home Learning Packet Table of Contents • Daily Assignments • Vocabulary Games • Day1 L.8.4 • Days 2-4 E.8.7 • Days 5 -11 E.8.9.A • Days 12-15 P.8.6 8th Grade Daily Science Assignments: Day 1. Read and answer questions from - Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Day 2. Use Earth’s Student Guides to Create Vocabulary Flashcards – define and use word in a sentence. You can use flashcards to play any of the vocabulary games on Vocabulary Game Sheet: Weathering, Erosion, Deposition, Sedimentary, Igneous, Metamorphic, Plates Answer Questions: What causes rock to change? How are rocks classified? What do fossils provide ? Day 3. Use Earth’s Student Guide to draw and label the stages of the rock cycle. Explain how Each type of rock is formed. (Sedimentary, Igneous and Metamorphic) Day 4. Work Fossil Layers worksheet and Rock Cycle crossword Day 5. Use the Earth Student Guide to draw and label the layers of the Earth. Also list each layer and what it is made up of. Day 6. Make three columns on your paper. In the 1st column write the word, in the 2nd column put the definition , in the 3rd column draw a picture or illustration. (You can cut apart and use for a game after completing ) Use the following terms : tectonic plate, crust, Alfred Wegener, convection current, Pangaea, inner core, Ring of Fire, ocean trench, transform boundary , earthquake, divergent boundary , convergent boundary, subduction zone, volcano Day 7. Read Plate Boundaries and answer questions Day 8. Work Plate Tectonics Sheet – on the back list examples of each type of boundary and draw an example Day 9. -

3. Dancing Lessons: Hearing the Beat and Understanding the Body

Learning to Listen, Learning to Be: African-American Girls and Hip-Hop at a Durham, NC Boys and Girls Club by Jennifer A. Woodruff Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ John L. Jackson ___________________________ Mark Anthony Neal ___________________________ Diane Nelson ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT Learning to Listen, Learning to Be: African-American Girls and Hip-Hop at a Durham, NC Boys and Girls Club by Jennifer A. Woodruff Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ John L. Jackson ___________________________ Mark Anthony Neal ___________________________ Diane Nelson ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jennifer A. Woodruff 2009 Abstract This dissertation documents African-American girls’ musical practices at a Boys and Girls Club in Durham, NC. Hip-hop is the cornerstone of social exchanges at John Avery, and is integrated into virtually all club activities. Detractors point to the misogyny, sexual exploitation and violence predominant in hip-hop’s most popular incarnations, suggesting that the music is a corrupting influence on America’s youth. Girls are familiar with these arguments, and they appreciate that hip-hop is a contested and sometimes illicit terrain. Yet they also recognize that knowledge about and participation in hip-hop-related activities is crucial to their interactions at the club, at school, and at home. -

American Art

American Art The Art Institute of Chicago American Art New Edition The Art Institute of Chicago, 2008 Produced by the Department of Museum Education, Division of Teacher Programs Robert W. Eskridge, Woman’s Board Endowed Executive Director of Museum Education Writers Department of American Art Judith A. Barter, Sarah E. Kelly, Ellen E. Roberts, Brandon K. Ruud Department of Museum Education Elijah Burgher, Karin Jacobson, Glennda Jensen, Shannon Liedel, Grace Murray, David Stark Contributing Writers Lara Taylor, Tanya Brown-Merriman, Maria Marable-Bunch, Nenette Luarca, Maura Rogan Addendum Reviewer James Rondeau, Department of Contemporary Art Editors David Stark, Lara Taylor Illustrations Elijah Burgher Graphic Designer Z...ART & Graphics Publication of American Art was made possible by the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Woman’s Board of the Art Institute of Chicago. Table of Contents How To Use This Manual ......................................................................... ii Introduction: America’s History and Its Art From Its Beginnings to the Cold War ............... 1 Eighteenth Century 1. Copley, Mrs. Daniel Hubbard (Mary Greene) ............................................................ 17 2. Townsend, Bureau Table ............................................................................... 19 Nineteenth Century 3. Rush, General Andrew Jackson ......................................................................... 22 4. Cole, Distant View of Niagara Falls .................................................................... -

NBTT: Transitions, Chris Bronstein

Nothing But the Truth So Help Me God Nothing But the Truth So Help Me God 73 Women on Life’s Transitions Author ABOW Editors Mickey Nelson and Eve Batey SAN FRANCISCO © 2014 Nothing But The Truth, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechan- ical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permissions in writing from the publisher, Nothing But The Truth, LLC. Nothing But The Truth, LLC 980 Magnolia Avenue, Suite C-6 Larkspur, CA 94939 Nothing But The Truth So Help Me God: 73 Women on Life’s Transitions™ and Nothing But The Truth So Help Me God: 73 Women on Life’s Transitions Cover Design are trademarks of Nothing But The Truth, LLC. For information about book purchases please visit the Nothing But The Truth website at NothingButtheTruth.com Also available in ebook. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936237 Nothing But The Truth So Help Me God: 73 Women on Life’s Transitions Compiled by A Band of Women Eve Batey, Editor. Mickey Nelson, Editor. ISBN 978-0-9883754-6-8 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-9883754-7-5 (ePub ebook) ISBN 978-0-9883754-8-2 (Kindle ebook) Printed in the United States of America Cover design by theBookDesigners, Fairfax, CA First Edition Contents Introduction Shasta Nelson / ix Section One: Moving On, Letting Go Love You Hard Abby Maslin / 1 The Shopping Trip Leslie Lagerstrom / 5 The Last Drop Sierra Godfrey / 9 Finally Fall Ashley Collins / 13 Home(less) and Gardens Heather Kristin / 16 I Think I’ll Make It Kat Hurley / 20 One Thought to Keep Sierra Trees / 25 Bloom Where You Are Planted Christine A. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Welcome To Jermaine Local 1 Atlanta (Clean 5:03 Instructions 2 2001 Rap 128 Dupri Disk Remix) Nas & Ill Will Oochie Wally Local 2 QB's Finest 3:58 Records Presents 4 2000 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk Queensbr Local 3 Jay Z La-La-La (Clean) 4:40 Bad Boys II 3 2003 Rap 1 171 Disk Destiny's Local 4 Cater 2 U 4:09 Destiny Fulfilled 3 2004 Pop 5 128 Child Disk Local 5 Ja Rule Wonderful 4:26 R.U.L.E. 3 2004 Rap 128 Disk Local 6 Bob Acri Sleep Away 3:20 Bob Acri 3 2004 Jazz 3 128 Disk We Takin' Over Local 7 DJ Khaled 4:28 We The Best 13 2007 Rap 128 (Remix) Disk Light Poles and Pine Local 8 Field Mob So What (Clean) 3:36 3 2006 Rap 128 Trees Disk Always On Time Local 9 Ja Rule 4:06 Pain Is Love 2001 Rap 3 128 (Clean) Disk Welcome To Tha Local 10 Snoop Dogg Fly (Clean) 4:08 19 2005 Rap 2 200 Chuuch, Vol.3 Disk Feelin' On Yo Local 11 R Kelly 4:05 TP-2.com 18 2000 RnB 128 Booty Disk Local 12 YG Rack On Racks 4:45 We In School 2002 Rap 128 Disk Brian For The Rest Of Local 13 3:34 U Turn 9 2003 RnB 128 Mcknight My Life Disk Donnie Donnie McClurkin... Local 14 I'm Walking 5:19 8 2003 Gospel 128 Mcclurkin Again Disk Local 15 Baby Bash What Is It (Clean) 3:20 Cyclone 5 2007 Rap 128 Disk From Tha Paid tha Cost to Be Local 16 Snoop Dogg Chuuuch Ta Da 4:40 4 2002 Rap 128 da Bo$$ Disk Palace Jermaine Dupri Jermaine Gotta Get'cha Presents...Young Fly Local 17 2:49 2 2005 Rap 128 Dupri (Clean) and Flashy, Vol. -

Dear Honor Students, This Summer 7Th Grade Honor Classes Will Read a Single Shard Written by Linda Sue Park

Dear Honor Students, This summer 7th grade Honor classes will read A Single Shard written by Linda Sue Park. You are responsible for purchasing a copy of the book. Please read the novel and complete both an essay as well as one of the following activities. Both project and essay are due August 08, 2019. A copy of this letter has been placed on the CMS website. **HINT: Once you return to school, you will take a test on this novel. A Single Shard test will be August 13, 2019. Poster Requirements: 1. Posters should be neat, creative, and colorful. 2. Posters must have two-inch border on all sides. (This can be decorated or left on white.) 3. The entire poster must be covered with content and graphics and should show no white spaces (except for the two-inch border.) (USE A NORMAL SIZE POSTER) 4. The poster should have the title and author displayed largely and creatively at the top of the poster. 5. The poster should include AT LEAST THREE QUOTATIONS FROM THE NOVEL. EACH QUOTATION MUST BE EXPLAINED AND MUST INCLUDE WHO SAID IT. 6. The poster should include at least three hand-drawn graphics AND at least three pictures from a magazine, newspaper, snapshot, etc. that connects to the novel in some way. Or Photo Album: 1. Album should include at least 10 pictures. Pictures must be both hand drawn and cut from a magazine, book, or newspaper, snapshot, etc. Under each picture a description of the photo and the importance of the photo are required. -

THE EARLY DAYS: a Sourcebook of Southwestern Region History

THE EARLY DAYS: A Sourcebook of Southwestern Region History Book 1 Compiled by Edwin A. Tucker Supervisory Management Analyst Division of Operations Cultural Resources Management Report No. 7 USDA Forest Service Southwestern Region September 1989 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover: An open pine forest covering Smith's Butte, Tusayan National Forest, October 18, 1913. Photo by A. Gaskill. This publication is part of a Southwestern Region series detailing the cultural resources of the Region. Tables Figures Foreword Acknowledgements Editor's Foreword SECTIONS Setting The Scene Correspondence National Forests The Waha Memorandum The Fred Winn Papers Personal Stories Fred Arthur Leon F. Kneipp Richard H. Hanna Tom Stewart Frank E. Andrews Roscoe G. Willson Henry L. Benham Elliott S. Barker Lewis Pyle Robert Springfel C. V. Shearer F. Lee Kirby William H. Woods Edward G. Miller Henry Woodrow Benton S. Rogers Jesse I. Bushnell John D. Guthrie Apache Ranger Meeting Short Histories Over Historic Ground by John D. Guthrie History of Datil National Forest (Anon.) History of Grazing on the Tonto, by Fred Croxen Interviews Fred W. Croxen Quincy Randles Fred Merkle Edward Ancona Morton C. Cheney Stanley F. Wilson Paul Roberts TABLES 1. National Forests in District 3 in 1908 FIGURES 1. Santa Fe Forest Reserve Office in 1902 2. The first Ranger meeting, in 1903 on the Gila Forest Reserve 3. Gila Supervisor McClure and Forest Officers in 1903 4. Old Bear Canyon Ranger Station. Gila National Forest in 1907 5. Supervisor McGlone, Chiricahua N. F. in 1904 6. Tonto Supervisor's cottage at Roosevelt in 1913 7. The combined Gila and Datil Ranger Meeting at Silver City in 1908 8. -

Icons of Hip Hop: an Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, Volumes 1 & 2

Icons of Hip Hop: An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture, Volumes 1 & 2 Edited by Mickey Hess Greenwood Press ICONS OF HIP HOP Recent Titles in Greenwood Icons Icons of Horror and the Supernatural: An Encyclopedia of Our Worst Nightmares Edited by S.T. Joshi Icons of Business: An Encyclopedia of Mavericks, Movers, and Shakers Kateri Drexler ICONS OF HIP HOP An Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, And Culture VOLUME 1 Edited by Mickey Hess Greenwood Icons GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut . London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Icons of hip hop : an encyclopedia of the movement, music, and culture / edited by Mickey Hess p. cm. – (Greenwood icons) Includes bibliographical references, discographies, and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33902-8 (set: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33903-5 (vol 1: alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33904-2 (vol 2: alk. paper) 1. Rap musicians—Biography. 2. Turntablists—Biography. 3. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. 4. Hip-hop. I. Hess, Mickey, 1975– ML394. I26 2007 782.421649'03—dc22 2007008194 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright Ó 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007008194 ISBN-10: 0-313-33902-3 (set) ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33902-8 (set) 0-313-33903-1 (vol. 1) 978-0-313-33903-5 (vol. 1) 0-313-33904-X (vol. 2) 978-0-313-33904-2 (vol. -

Punk Subculture in Richmond, Virginia Christopher J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2006 Underground in the Confederate Capital: Punk Subculture in Richmond, Virginia Christopher J. Dalbom Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dalbom, Christopher J., "Underground in the Confederate Capital: Punk Subculture in Richmond, Virginia" (2006). LSU Master's Theses. 2955. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2955 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNDERGROUND IN THE CONFEDERATE CAPITAL: PUNK SUBCULTURE IN RICHMOND, VIRGINIA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Christopher J. Dalbom B.A., University of Kansas, 2001 December, 2006 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Dydia DeLyser, and my committee members, Dr. Miles Richardson and Dr. Kent Mathewson, for their enduring guidance and support. Friends Paul Watts, Christopher Hurst, David Farritor, Frances Currin, Dr. Joshua Gunn, and many others shared their views and experiences so that I might better my own research. Richmond punks provided their time and energy, especially Donna, Mark, Michelle, Andrew, Cloak/Dagger, I Live with Zombies, Army of Fun, and the Fortress of Solid Dudes.