Punk Subculture in Richmond, Virginia Christopher J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The Concert Hall As a Medium of Musical Culture: the Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19Th Century

The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century by Darryl Mark Cressman M.A. (Communication), University of Windsor, 2004 B.A (Hons.), University of Windsor, 2002 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Darryl Mark Cressman 2012 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2012 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for “Fair Dealing.” Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. Approval Name: Darryl Mark Cressman Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) Title of Thesis: The Concert Hall as a Medium of Musical Culture: The Technical Mediation of Listening in the 19th Century Examining Committee: Chair: Martin Laba, Associate Professor Andrew Feenberg Senior Supervisor Professor Gary McCarron Supervisor Associate Professor Shane Gunster Supervisor Associate Professor Barry Truax Internal Examiner Professor School of Communication, Simon Fraser Universty Hans-Joachim Braun External Examiner Professor of Modern Social, Economic and Technical History Helmut-Schmidt University, Hamburg Date Defended: September 19, 2012 ii Partial Copyright License iii Abstract Taking the relationship -

Gabrielle Gabrielle Mp3, Flac, Wma

Gabrielle Gabrielle mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Pop Album: Gabrielle Country: UK & Europe Released: 1996 Style: RnB/Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1402 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1863 mb WMA version RAR size: 1378 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 865 Other Formats: WAV DTS MOD AIFF VQF ADX VOX Tracklist Hide Credits Forget About The World Backing Vocals – Andy Caine, Tracey Ackerman*Bass, Acoustic Guitar, Electric Piano 1 4:19 [Fender Rhodes] – Ben BarsonDrums – Geoff DugmoreGuitar – Matt ColdrickPercussion – Louis Jardim*Strings – The London Session Orchestra People May Come Backing Vocals – Andy Caine, Tracey Ackerman*Bass, Acoustic Guitar, Piano – Ben 2 4:32 BarsonDrums – Geoff DugmoreKeyboards [Additional] – Paul Taylor Percussion – Louis Jardim*Strings – The London Session Orchestra I Live In Hope Backing Vocals – Andy Caine, Tracey Ackerman*Bass, Piano – Ben BarsonDrums – Geoff 3 4:11 DugmoreGuitar – Matt ColdrickKeyboards [Additional] – Paul Taylor Percussion – Louis Jardim*Strings – The London Session Orchestra Baby I've Changed 4 Bass, Guitar, Electric Piano [Fender Rhodes], Keyboards [Additional] – Ben BarsonDrums – 4:44 Geoff DugmorePercussion – Louis Jardim* Give Me A Little More Time Backing Vocals – Andy Caine, Tracey Ackerman*Bass, Guitar, Piano – Ben BarsonBrass – 5 4:55 The Kick HornsDrums – Geoff DugmorePercussion – Louis Jardim*Strings – The London Session Orchestra If You Really Cared Bass, Piano – Ben BarsonBrass – Jamie Talbot, John Barclay, Pete Beechill*, Phil Todd, 6 4:54 Steve SidwellDrums – Geoff -

Directory Download Our App for the Most Up-To-Date Directory Info

DIRECTORY DOWNLOAD OUR APP FOR THE MOST UP-TO-DATE DIRECTORY INFO. E = East Broadway N = North Garden C = Central Parkway S = South Avenue W = West Market m = Men’s w = Women’s c = Children’s NICKELODEON UNIVERSE = Theme Park The first number in the address indicates the floor level. ACCESSORIES Almost Famous Body Piercing E350 854-8000 Chapel of Love E318 854-4656 Claire’s E179 854-5504 Claire’s N394 851-0050 Claire’s E292 858-9903 GwiYoMi HAIR Level 3, North 544-0799 Icing E247 854-8851 Soho Fashions Level 1, West 854-5411 Sox Appeal W391 858-9141 APPAREL A|X Armani Exchange m w S141 854-9400 abercrombie c W209 854-2671 Abercrombie & Fitch m w N200 851-0911 aerie w E200 854-4178 Aéropostale m w N267 854-9446 A’GACI w E246 854-1649 Alpaca Connection m w c E367 883-0828 Altar’d State w N105 763-489-0037 American Eagle Outfitters m w S120 851-9011 American Eagle Outfitters m w N248 854-4788 Ann Taylor w S218 854-9220 Anthropologie w C128 953-9900 Athleta w S145 854-9387 babyGap c S210 854-1011 Banana Republic m w W100 854-1818 Boot Barn m w c N386 854-1063 BOSS HUGO BOSS m S176 854-4403 Buckle m w c E203 854-4388 Burberry m w S178 854-7000 Calvin Klein Performance w S130 854-1318 Carhartt m w c N144 612-318-6422 Carter’s baby c S254 854-4522 Champs Sports m w c W358 858-9215 Champs Sports m w c E202 854-4980 Chapel Hats m w c N170 854-6707 Charlotte Russe w E141 854-6862 Chico’s w S160 851-0882 Christopher & Banks | c.j. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

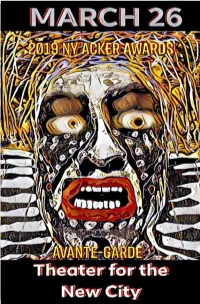

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

Information and Secrecy in the Chicago DIY Punk Music Scene Kaitlin Beer University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 "It's My Job to Keep Punk Rock Elite": Information and Secrecy in the Chicago DIY Punk Music Scene Kaitlin Beer University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Beer, Kaitlin, ""It's My Job to Keep Punk Rock Elite": Information and Secrecy in the Chicago DIY Punk Music Scene" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1349. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1349 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “IT’S MY JOB TO KEEP PUNK ROCK ELITE”: INFORMATION AND SECRECY IN THE CHICAGO DIY PUNK MUSIC SCENE by Kaitlin Beer A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT “IT’S MY JOB TO KEEP PUNK ROCK ELITE”: INFORMATION AND SECRECY IN THE CHICAGO DIY PUNK MUSIC SCENE by Kaitlin Beer The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor W. Warner Wood This thesis examines how the DIY punk scene in Chicago has utilized secretive information dissemination practices to manage boundaries between itself and mainstream society. Research for this thesis started in 2013, following the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s meeting in Chicago. This event caused a crisis within the Chicago DIY punk scene that primarily relied on residential spaces, from third story apartments to dirt-floored basements, as venues. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

Graphics Incognito

45 amateur, trendy, and of-the-moment. The irony, What We Do Is Secret the subject of spirited disagreement and post-hoc of course, being that over the subsequent two speculation both by budding hardcore punks decades punk and graffiti (or, more precisely, One place to begin to consider the kind of and veteran scenesters over the past twenty-five GRAPHICS hip-hop) have proven to be two of the most crossing I am talking about is with the debut years. According to most accounts, ‘GI’ stands productive domains not only for graphic design, (and only) album by the legendary Los Angeles for ‘Germs Incognito’ and was not originally INCOGNITO but for popular culture at large. Meanwhile, punk band the Germs, titled simply ����.5 intended to be the title of the album. By the time Rand’s example remains a source of inspiration The Germs had formed in 1977 when teenage the songs were recorded the Germs had been by Mark Owens to scores of art directors and graphic designers friends Paul Beahm and George Ruthen began banned from most LA clubsclubs andand hadhad resortedresorted to weaned on breakbeats and powerchords. writing songs in the style of their idols David booking shows under the initials GI. Presumably And while I suppose it might be possible to see Bowie and Iggy Pop. After the broadcast of a in order to avoid confusion, the band had wanted My interest has always been in restating Rand’s use of techniques like handwriting, ripped London performance by The Clash and The Sex the self-titled LP to read ‘GERMS (GI)’, as if it the validity of those ideas which, by and paper, and collage as sharing certain formal Pistols on local television a handful of Los Angeles were one word. -

International Students Reflect on Floyd Widener ~Ware Campus Closed Due to Floyd's Effects

THE STUDENT .; .... :.;.;.:::::: ::::: ~ :c. .~ NEWSPAPER OF ....... :.: ::.::::::~::: :«0:::::::::: :::. WIDENER UNIVERSITY http://dome.life.nu Covering the good stuff (610) 499'4.421 INSIDE ENTERTAINMENT NEWS SPORTS University 2 Philadelphia 3 NY Surrenders Widener students Women's V Opinion 4 to Chemical Comics/Games 6 Ball p.12 Brothers p.8 abroad p.2 Entertainment 8 WIDENER PROFESSOR PASSES AWAY, Widener Feels Floyd SAYING FAIRWELL TO DR. CLARK. Ben Myers Brian O'Rourke RELATIONS MANAGER The University suffered a terrible first faculty member to participate in the STAFF WRITER defeat two weeks ago, when Dr. Michael German Exchange Program. Clark passed away. Dr. Clark Both teachers and students gave the Hurricane Floyd which passed along joined Widener IS faculty in 1981, same answers in describing- Dr. Clark: after receiving his Ph.D. from the IIFine mind ... very accessible ... down-to the east coast on September 18, 19, and University of Wisconsin-Madison. earth... he was the best in the 20 left devastation everywhere. Causing He was a professor of English and Department. II Dr. Lopota, a colleague for a time, the Associate Dean of hired by Dr. Clark, said, IIHe was the massive flooding and property damage Humanities. type of guy who could write two books Dr. Clark had a hand in just on Dos Passos, and then turn around in the Carolinas, Floyd also caused dam and have a drink with you at WalliolS. 1I about every facet of English at age along the upper east coast. In New Widener University. He did not Dr. Serambis, present Associate Dean speak the English language, he of Humanities, had this to say of his Jersey and Delaware states of emergen commanded it. -

Never Mind the Sex Pistols, Hereâ•Žs CBGB the Role of Locality and DIY

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2020 Never mind the sex pistols, here’s CBGB the role of locality and DIY media in forming the New York punk scene Ariana Bowe Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Bowe, Ariana, "Never mind the sex pistols, here’s CBGB the role of locality and DIY media in forming the New York punk scene" (2020). Senior Capstone Projects. 1052. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/1052 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bowe 1 Vassar College Never Mind The Sex Pistols, Here’s CBGB The Role of Locality and DIY Media in Forming the New York Punk Scene A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Bachelor of Arts in Media Studies. By Ariana Bowe Thesis Advisers: Professor Justin Patch May 2020 Bowe 2 Project Statement In my project, I will explore the New York City venue CBGB as one of the catalysts behind the rise of punk subculture in the 1970s. In a broader sense, I argue that punk is defined by a specific local space that facilitated a network of people (the subculture’s community), the concepts of DIY and bricolage, and zines. Within New York City, the locality of the punk subculture, ideas and materials were communicated via a DIY micro-medium called zines.