Comcast Ex Parte of 11-4-14 in GN Docket 14-28

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUE BLAINEY, ACE Editor

SUE BLAINEY, ACE Editor PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS POWER BOOK III: RAISING KANAN Various Directors STARZ / LIONSGATE TV Season 1 Tim Christenson, Bart Wenrich Shana Stein, Courtney Kemp, Sascha Penn THE WALKING DEAD: WORLD BEYOND Michael Cudlitz AMC Season 1, Episode 7 Jonathan Starch, Matt Negrete THE GOOD LORD BIRD Albert Hughes SHOWTIME / BLUMHOUSE Limited Series O’Shea Read, Olga Hamlet STRANGE ANGEL David Lowery SCOTT FREE / CBS Pilot & Season 1 - 2 David Zucker, Mark Heyman WHAT IF Various Directors WARNER BROS. / NETFLIX Series Mike Kelley 13 REASONS WHY Various Directors PARAMOUNT TV / NETFLIX Season 2 Kim Cybulski, Brian Yorkey ANIMAL KINGDOM Various Directors WARNER BROS. / TNT Season 1 Terri Murphy, Lou Wells 11/22/63 Kevin MacDonald BAD ROBOT / HULU Series Jill Risk, Bridget Carpenter THE MAGICIANS Mike Cahill SYFY / Desiree Cadena, John McNamara Pilot Michael London MOZART IN THE JUNGLE Paul Weitz AMAZON Season 1 Caroline Baron, Roman Coppola Jason Schwartzman, Paul Weitz UN-REAL Roger Kumble LIFETIME Pilot Sarah Shapiro, Marti Noxon IN PLAIN SIGHT Various Directors NBC Season 3 Dan Lerner, John McNamara Consulting Producer Karen Moore HAPPY TOWN Darnell Martin ABC Season 1 Mick Garris Paul Rabwin, Josh Appelbaum John Polson André Nemec EASY VIRTUE Stephan Elliott EALING STUDIOS Toronto Film Festival Barnaby Thompson, Alexandra Ferguson THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2 Martin Weisz FOX / ATOMIC Co-Editor Wes Craven, Marianne Maddalena SIX DEGREES David Semel BAD ROBOT / ABC Series Wendey Stanzler J.J. Abrams, Jane Raab, Bryan Burke LOST Jack Bender ABC Season 2 Finale J.J. Abrams, Ra’uf Glasgow, Bryan Burke Nomination, Best Editing – ACE Eddie Awards Nomination, Best Editing – Emmy Awards HOUSE Greg Yaitanes FOX Series Keith Gordon Katie Jacobs, David Shore SIX FEET UNDER Kathy Bates HBO Series Migel Arteta Alan Ball, Alan Poul Lisa Cholodenko THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA Stephan Elliott POLYGRAM QUEEN OF THE DESERT Al Clark, Michael Hamlyn Cannes Film Festival INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

The Polygram, April 25, 1924

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DigitalCommons@CalPoly v : . • ■ .. a, . -s__ _ . J / 916—Birthday Number— 1924 Tiie News School and Josh Spirit Box Is Is Poly’s Calling Best You Asset Volume IX , , SAN MMS OMISl'O, APRIL 25. PCI No. 15 ~ eFght y e a r s bu>! I' ROM FIRST POLYGRAM THE SCHOOL PLAY - - JL STAYING ROWER On Tuesday, April 2<r>t Ml HI, the Character Counts After much deliberation, the school (From the Placement Bureau) flnt- Polygram appeared on our cam- That you may develop the power to pus, It was only a small puper, being. Richard Cohden once asked h pluy was finally decided-upon. It Is to con- lie a snappy, Interesting one, entlfM stick, stick, to ydur word, stick to 8 by 11 in slzu, having four pages but ccrn from which he bought Roods, your ideals, stick to the right, stick no advertisements. However, It was "The Seven Keys to Huldpate," having "Why do you extend to me over plenty of action which cannot help but to your job. One of the most out a lively edition and the students were hold the audience's attention. It is standing characteristics which must insured that in time a real puper $2(10,000 worth of credit when you know that I urn worth only $10,000 in not a cheap production and must lie be corrected in our American boy* and would represent the school. Every girls is their desire to ehange and my own righ t?” backed by the whole student body. -

Samuelson Clinic Files Amicus Brief in Sony V. Cox

USCA4 Appeal: 21-1168 Doc: 29-1 Filed: 06/01/2021 Pg: 1 of 43 Case No. 21-01168 _____________________________________________________________ IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT ____________________________________________________ SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, ET AL., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. COX COMMUNICATION, INC. and COXCOM, LLC, Defendants-Appellants. (see full caption on inside cover) _____________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION, CENTER FOR DEMOCRACY AND TECHNOLOGY, AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION, ASSOCIATION OF COLLEGE AND RESEARCH LIBRARIES, ASSOCIATION OF RESEARCH LIBRARIES, AND PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS- APPELLANTS AND REVERSAL ____________________________________________________ On Appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia Case No. 1:18-cv-950-LO-JFA Hon. Liam O’Grady _____________________________________________________________ Mitchell L. Stoltz Corynne McSherry ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION 815 Eddy Street San Francisco, California 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae (Additional counsel listed on signature page) USCA4 Appeal: 21-1168 Doc: 29-1 Filed: 06/01/2021 Pg: 2 of 43 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT; ARISTA MUSIC; ARISTA RECORDS, LLC; LAFACE RECORDS LLC; PROVIDENT LABEL GROUP, LLC; SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT US LATIN LLC; VOLCANO ENTERTAINMENT III, LLC; ZOMBA RECORDINGS LLC; SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING LLC; EMI AL GALLICO MUSIC CORP.; EMI ALGEE MUSIC CORP.; EMI APRIL MUSIC INC.; EMI BLACKWOOD MUSIC INC.; COLGEMS-EMI MUSIC INC.; EMI CONSORTIUM MUSIC PUBLISHING INC., d/b/a EMI Full Keel Music; EMI,CONSORTIUM SONGS, INC., d/b/a EMI Longitude Music; EMI FEIST CATALOG INC.; EMI MILLER CATALOG INC.; EMI MILLS MUSIC, INC.; EMI UNART CATALOG INC.; EMI U CATALOG INC.; JOBETE MUSIC CO. -

Annual Financial Report and Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the Year Ended December 31, 2007

Annual Financial Report and Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the Year ended December 31, 2007 VIVENDI Société anonyme with a Management Board and Supervisory Board with a share capital of €6,406,087,710.00 Head Office: 42 avenue de Friedland – 75380 PARIS CEDEX 08 – FRANCE IMPORTANT NOTICE: READERS ARE STRONGLY ADVISED TO READ THE IMPORTANT DISCLAIMERS AT THE END OF THIS FINANCIAL REPORT. Annual Financial Report and Audited Consolidated Financial Statements for the Year Ended December 31, 2007 Vivendi /2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SELECTED KEY CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL DATA........................................................................................................................................6 I – 2007 FINANCIAL REPORT ...............................................................................................................................................................................7 1 MAIN DEVELOPMENTS..............................................................................................................................................................................8 1.1 MAIN DEVELOPMENTS IN 2007......................................................................................................................................................................8 1.2 MAIN DEVELOPMENTS SINCE DECEMBER 31, 2007 ........................................................................................................................................11 1.3 TRANSACTIONS UNDERWAY AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2007 .................................................................................................................................11 -

TIU S5E4 Transcript

The Liquid Workforce Krissy Clark: Hey it’s Krissy. This is the Uncertain Hour. If you’ve been listening to our whole season (which, if you’re not, you should), you’ll know the last few episodes have been about Jerry Vazquez, a former janitor who was not employed by the company whose name was on his uniform, or by the companies whose offices he cleaned. At one point most corporations, schools, churches - had their own in-house janitors who were their employees. Not so much anymore. And on today’s episode we’re looking at how did that come to be? Not just for janitors, but for so many people. Which is why Uncertain Hour producer Peter Balonon-Rosen and I sat down with a guy named Bryan Peña. Peter Balonon-Rosen: And Bryan told us how, decades ago, he worked beneath the bright fluorescent lights at a 7-Eleven in San Diego. BP: You wanna learn about people? You know that’s a great job to learn about people. Peter: Why do you say that? BP: Because you see people of all shapes, sizes and colors in different states. Peter: It was the early ‘90s and Bryan was paying his way through college, working the graveyard shift at 7-Eleven. He was majoring in economics, minoring in acting, so Bryan was fascinated with human behavior. And at 7-Eleven, he got to see that up close. BP: We'd have the guy who had no teeth who would buy 17 cans of easy cheese every Tuesday. Peter: OK BP: We had the guy who lived in back who would get donuts. -

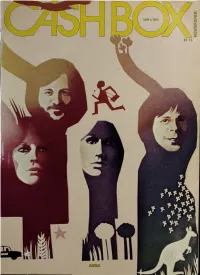

CB-1978-04-01.Pdf

This is the twentieth anni- versary of Bobby Bare s first hit. It was “The All-American Boy,” and though the name on the label read Bill Parsons, the man who did the singing was Bare. After a long series of “straight” hits like “Detroit City” and “500 Miles (Away From Home)’ Bobby Bare fell in with Shel Silverstein and began having hits in the lighthearted, funky, narra- tive style that Bare originally in- vented on “The All-American Boy.” Last year Bare scored big with “The Winner.” This year he’s delivered a totally winning album... his first on Columbia... including the single “Too Many Nights Alone.” Listen to the new single and album and we think you’ll agree that the future looks Bare. “Bare*.’ KC 35314 Including the single “Too Many Nights Alone? The new Bobby Bare on Columbia Records and Tapes. "Columbia!’ ^ are trademarks of CBS Inc. © 1978 CBS Inc. VOLUME XXXIX — NUMBER 46 — April 1, 1378 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC RECORD WEEKLY G4SHBCK GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher EDITORIAL MEL ALBERT General Manager Back To The Basics DAVE FULTON Clive Davis’ keynote address at the recent NARM we cannot afford for the human element to be miss- Editor In Chief convention contained a number of controversial ing.” J, B. CARMICLE statements that still have the industry buzzing. During the convention the president of a major General Manager, East Coast However, to dwell only on the controversies is a mis- record company told Cash Box that he didn’t have to East Coast Editorial take because the crux of Davis’ speech concerned spend millions of dollars to purchase a major artist KEN TERRY. -

Authorized Catalogs - United States

Authorized Catalogs - United States Miché-Whiting, Danielle Emma "C" Vic Music @Canvas Music +2DB 1 Of 4 Prod. 10 Free Trees Music 10 Free Trees Music (Admin. by Word Music Group, 1000 lbs of People Publishing 1000 Pushups, LLC Inc obo WB Music Corp) 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers SESAC Designee 10000 MINUTES 1012 Rosedale Music 10KF Publishing 11! Music 12 Gate Recordings LLC 121 Music 121 Music 12Stone Worship 1600 Publishing 17th Avenue Music 19 Entertainment 19 Tunes 1978 Music 1978 Music 1DA Music 2 Acre Lot 2 Dada Music 2 Hour Songs 2 Letit Music 2 Right Feet 2035 Music 21 Cent Hymns 21 DAYS 21 Songs 216 Music 220 Digital Music 2218 Music 24 Fret 243 Music 247 Worship Music 24DLB Publishing 27:4 Worship Publishing 288 Music 29:11 Church Productions 29:Eleven Music 2GZ Publishing 2Klean Music 2nd Law Music 2nd Law Music 2PM Music 2Surrender 2Surrender 2Ten 3 Leaves 3 Little Bugs 360 Music Works 365 Worship Resources 3JCord Music 3RD WAVE MUSIC 4 Heartstrings Music 40 Psalms Music 442 Music 4468 Productions 45 Degrees Music 4552 Entertainment Street 48 Flex 4th Son Music 4th teepee on the right music 5 Acre Publishing 50 Miles 50 States Music 586Beats 59 Cadillac Music 603 Publishing 66 Ford Songs 68 Guns 68 Guns 6th Generation Music 716 Music Publishing 7189 Music Publishing 7Core Publishing 7FT Songs 814 Stops Today 814 Stops Today 814 Today Publishing 815 Stops Today 816 Stops Today 817 Stops Today 818 Stops Today 819 Stops Today 833 Songs 84Media 88 Key Flow Music 9t One Songs A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd A Beautiful Liturgy Music A Few Good Tunes A J Not Y Publishing A Little Good News Music A Little More Good News Music A Mighty Poythress A New Song For A New Day Music A New Test Catalog A Pirates Life For Me Music A Popular Muse A Sofa And A Chair Music A Thousand Hills Music, LLC A&A Production Studios A. -

RENTRAK Worldwide Film Distributors

RENTRAK Worldwide Film Distributors ABBREVIATED NAME FULL NAME 518 518 Media 757 7-57 Releasing 1211 1211 Entertainment 2020 2020 Films @ENT At Entertainment @MOV @MOVIE JAPAN +me +me 01 DIST 01 Distribution 104 FLM 104 Films 11ARTS Eleven Arts 120D 120 Degree Films 13DIST Les Films 13 Distribution 1A FLM 1A Films 1CUT 1st Cut 1M60FILM 1meter60 Film 1MRFM 1 More Film 1ST INDP First Independent 1stRUN First Run 21ST 21st Century 21ST CENT Twenty First Century Films 24BD 24 Bilder 24FRMS 24 Frames 2Corzn Dos Corazones 2GN 2nd Generation 2MN Two Moon 2ND GEN Second Generation Films 2RIVES Les Films des Deux Rives 2SR 2 Silks Releasing 35MI 35 Milim Filmcilik 360 DEGREE 360 Degrees Film 3DE 3D Entertainment 3ETAGE Productions du 3e Etage 3L 3L 3MONDE La Médiathèque des Trois Mondes 3RD WINDOW Third Window Fims 3ROS 3Rosen 41Inc 41 Inc 42FILM 42film 45RDLC 45 RDLC 4DIGITAL 4Digital Media Ltd 4STFM Four Star Film 4TH 4th & Broadway 4TH DIG 4TH Digital Asia 5&2 Five & Two Pictures 50TH 50th Street 5PM Five Points Media 5STR Five Star Trading 5STRET Five Star Entertainment 6PCK Sixpack-Film 791C 791 Cine 7ARTS Seven Arts Distribution 7FLR The 7th Floor 7PP 7th Planet Prods 7TH ART Seventh Art Production 8X 8X Entertainment A B FILM A.B. Film Distributors A. LEONE Andrea Leone Films A3DIST A3 Distribution AA AA Films AAA Acteurs Auteurs Associés (AAA) AAAM Arts Alliance America AAC Alliance Atlantis Communications AAM Arts Alliance Media Aanna Aanna Films AARDMAN Aardman Animations AB&GO AB & GO ABBEY Abbey Home Entertainment ABCET ABC Entertainment ABCF ABC-Films ABFI Absinthe Films ABH Abhi Films ABKCO ABKCO Films ABLO Ablo ABR Abramorama Entertainment ABS ABS-CBN ABSOLUT Absolut media ACADRA ACADRA Distribution ACAF Acacia Films Acajou Acajou Films ACCDIS Accatone Distribution ACCTN Accatone ACD Academy ACE Ace Films ACHAB Achab Film AchimHae Achim Hae Nori ACM Access Motion Picture Group ACME ACME ACOMP A Company ACONTRA A contracorriente ACROB Acrobate Films ACT/TDT Actions Cinémas/Théâtre du Temple ACTAEON Actaeon Film Ltd. -

Final Order and Oppinion of the Commission

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS: Timothy J. Muris, Chairman Sheila F. Anthony Mozelle W. Thompson Orson Swindle Thomas B. Leary In the Matter of POLYGAAM HOLDING, INC., a corporation DECCA MUSIC GROUP LIMITED, a corporation, UMG RECORDINGS, INC., Docket No. 9298 . a corporation, and UNIVERSAL MUSIC & VIDEO DISTRIBUTION CORP., a corporation. FINAL ORDER The Commssion has heard this matter on Respondents ' appeal from the Initial Decision and on briefs and oral argument in support of and in opposition to the appeal. For the reasons stated in the accompanying Opinion of the Commssion, the Commission has determned to affirm the Initial Decision and enter the following order. Accordingly, IT IS ORDERED that, as used in this order, the following definitions shall apply: 1. "PolyGram Holding" means PolyGram Holding, Inc., its directors officers, employees, agents, representatives, successors, and assigns; its subsidiaries, divisions, groups, and affiliates controlled by PolyGram Holding, Inc.; and the respective directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives successors, and assigns of each. 2. "Decca Music" means Decca Music Group Limited, its directors officers employees agents, representatives, successors, and assigns; its subsidiaries, divisions, groups, and affiliates controlled by Decca Music Group Limited; and the respective directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives successors, and assigns of each. 3. "UMG" means UMG Recordings, Inc., its directors, officers employees, agents, representatives, successors, and assigns'; its subsidiaries divisions, groups, and affiliates controlled by UMG Recordings, Inc.; and the respective directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives, successors, and assigns of each. 4. "UMVD" means Universal Music & Video Distrbution Corp. , its directors, officers, employees, agents, representatives, successors, and 'assigns; its subsidiaries, divisions, groups, and affiliates controlled by Universal Music & Video Distrbution Corp. -

Download the Pdf

LETTER TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS TOGETHER SEPTEMBER 2019 EARNINGS P. 3 NEWS P. 4 DIARY P. 8 — 2019 half-year — Universal Music Group, close links — Shareholders’ diary results between cinema and music Vivendi and you EDDY DE PRETTO_2018@MELCHIOR TERSEN LADY GAGA_A STAR IS BORN ©2018 WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT INC. LANGLANG_2018 @DR-UNIVERSAL MUSIC GROUP QUEEN_BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY Photos DR Photos SOLID PERFORMANCE FOR THE FIRST HALF OF 2019 Yannick Bolloré, Chairman of the Supervisory Board, and Arnaud de Puyfontaine, Chairman of the Management Board Dear Shareholders, t was with enthusiasm that, at the end of July, we published the results of your group for the first half of 2019: a very strong performance that confirms the solid growth dynamic observed for several months. Revenue exceeded €7.3 billion, up 6.7% compared to the first half of 2018, at constant currency and perimeter. This performance was driven by all our businesses. Universal Music Group (UMG) once again delivered outstanding results and propelled its artists to the top of the worldwide charts. Additionally, on August 6, Vivendi entered into preliminary negotiations with Tencent for a strategic investment of 10% in UMG at a preliminary equity evaluation of €30 billion and a one-year call option to acquire an additional 10%. This partnership would open up new opportunities for the group on the Chinese market. The process for the sale of an additional minority stake in UMG to other Ipotential partners is ongoing. Canal+ Group pursued its international expansion and announced its acquisition of pay- TV operator M7, allowing it to reach 20 million subscribers and establish itself in seven new countries. -

Estudis I Productores Amb Cobertura Sota La Llicència Umbrella MPLC

Productoras de la Licencia Umbrella MPLC® • 20th Century Fox Film • United International Company Pictures o 20th Century Fox Films o Universal o Fox Search Light o Paramount Pictures o Fox 2000 Films o Paramount Classics o Paramount Vantage o DreamWorks Animation SKG o DreamWorks Pictures o Republic Pictures o Dimension Films • Metro Goldwyn Mayer o United Artists o Orion o Polygram o Cannon • Warner Bros. * Relación de títulos disponible aquí o Warner Independent Pictures 3DD Entertainment A Contracorriente Films 9 Story Enterprises A&E Channel Home Video Acacia BogeyDom Enterprises ACI Boom Pictures Productions Acorn Group Border Television Acorn Media Boreales Films Actaeon Films Breakthrough Entertainment After Dark Films Bridgestone Multimedia Group/Alpha Omega Publishing Ager Film British and Foreign Bible Society Alameda Films Brook Lapping Productions All3media International Brown Eyed Boy Productions Allegro Pictures Burbank Animations Studios Alley Cat Films C3 Entertainment Alliance Atlantis Releasing C4i (DRG) American Portrait Films Cable Ready Anglia Television Cactus TV Animal Planet Video Cafe Productions Arte France Cake Entertainment Artemis Films Calon Ltd Associated Television Cambium Catalyst International (CCI) Athena Candlelight Media Atlantic Productions Cannon Pictures Australian Children's Television Foundation Carey Films Ltd Autlook Films Sales Cartoon One AV Pictures Caryn Mandabach Productions AWOL Animation Castle Hill Productions Baby Cow Productions Cats and Docs SAS Bankside Films CCI Releasing Bard Entertainment -

Vivendi 438X273 Ai.Pdpage 1 28/06/06 10:56:52

couverture_vivendi_438x273_ai.pdPage 1 28/06/06 10:56:52 C M J CM MJ CJ CMJ N VIVENDI - 2005 FORM 20-F FORM 20-F 2005 20-FAN2005 Head Office 42 avenue de Friedland - 75380 Paris cedex 08 - France Tel. : + 33 1 71 71 10 00 - Fax : + 33 1 71 71 10 01 New York Office 800 Third Avenue - New York, NY 10022 - USA Tel.: 1 (212) 572 - 7000 www.vivendi.com As Ñled with the Securities and Exchange Commission on June 29, 2006 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F n REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ¥ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Ñscal year ended December 31, 2005 OR n TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to n SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission File Number: 001-16301 VIVENDI S.A. (Exact name of Registrant as speciÑed in its charter) N/A Republic of France (Translation of Registrant's name into English) (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 42 avenue de Friedland 75380 Paris Cedex 08 France (Address of principal executive oÇces) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class on which registered Ordinary Shares, nominal value 45.50 per share New York Stock Exchange* American Depositary Shares (as evidenced by American Depositary Receipts), each representing one share, nominal value 45.50 per share New York Stock Exchange * Listed, not for trading or quotation purposes, but only in connection with the registration of American Depositary Shares, pursuant to the requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission.