Edinburgh Gardens Conservation Management Plan 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 October 2019

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, 17 OCTOBER 2019 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education ......................... The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Transport Infrastructure ............................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice and Minister for Victim Support .................... The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ............................................ The Hon. MP Foley, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Workplace Safety ................. The Hon. J Hennessy, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Ports and Freight -

This Entire Document

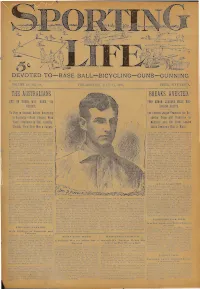

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL BICYCLING GUNS VOLUME 29, NO. 18. PHILADELPHIA, JULY 24, 1897. PRICE, FIVE CENTS. BREAKS AVERTED. ARE ON THEIR WAY HOME YIA TWO MINOR LEAGUES MAKE MID- EUROPE. SEASON SHIFTS, To Play in England Before Returning The Eastern League Transfers the Ro to Australia Much Pleased With chester Team and Franchise to Their Treatment in This Country, Montreal and the Texas League Though Their Trip Was a Failure, Shifts Denison©s Clnl) to Waco, Thirteen members of the Australian base For the first time in years a mid-season ball team sailed ou the 15th inst. from New change has been made in the Eastern York ou the American liner "St. Paul" for League circuit. Some time ago a stock England. Those in the party were: Man company was organized in Montreal by Mr. ager Harry Musgrove, Charles Over, Charles W. H. Rowe, with ample capital, with a Kemp, Walter G. Ingleton, Harry S. Irwin, view to purchasing an Eastern League fran Peter A. McAllister, Rue Ewers, Arthur chise. Efforts were made to buy either tlie K. Wiseman, Alfred S. Carter, J. H. Stuck- "Wilkesbarre or Kochester Clubs, both of ey, John Wallace and Frank Saver. which were believed to be in distress. The MU SGKOVE© S PLANS. former, however, was braced up and "We shall carry out our original inten will play out the season. Rochester tion ,of a trip around the world," said Mr. was on the fence regarding the Musgrove. ©-We shall probably play some proposition made when fate stepped in and de games in London and other parts of iCngland cided the question. -

One of the Boys: the (Gendered) Performance of My Football Career

One of the Boys: The (Gendered) Performance of My Football Career Ms. Kasey Symons PhD Candidate 2019 The Institute for Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities (ISILC), Victoria University, Australia. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Abstract: This PhD via creative work comprises an exegesis (30%) and accompanying novel, Fan Fatale (70%), which seek to contribute a creative and considered representation of some women who are fans of elite male sports, Australian Rules football in particular. Fictional representations of Australian Rules football are rare. At the time of submission of this thesis, only three such works were found that are written by women aimed to an older readership. This project adds to this underrepresented space for women writing on, and contributing their experiences to, the culture of men’s football. The exegesis and novel creatively addresses the research question of how female fans relate to other women in the sports fan space through concepts of gender bias, performance, and social surveillance. Applying the lens of autoethnography as the primary methodology to examine these notions further allows a deeper, reflexive engagement with the research, to explore how damaging these performances can be for the relationships women can have to other women. In producing this exegesis and accompanying novel, this PhD thesis contributes a new and creative way to explore the gendered complications that surround the sports fan space for women. My novel, Fan Fatale, provides a narrative which raises questions about the complicit positions women can sometimes occupy in the name of fandom and conformity to expected gendered norms. -

Variety Timeline: 1900-1999

AUSTRALIAN VARIETY AND POPULAR CULTURE ENTERTAINMENT: TIMELINE 1900-1999 Symbols Theatres ˟ Works (stage, film and music) ₪ Industry issues • People, troupes and acts ۩ ₣ Film 1900 ₪ Cato and Co: Herbert Cato sets up his own theatrical agency in Sydney. Tivoli Theatre [1] (Adelaide): Harry Rickards converts the Bijou Theatre into the Tivoli. It opens on 20 June ۩ with a company that includes Pope and Sayles, Prof Fred Davys and his Giant Marionettes, Neva Carr-Glynn and Adson, Craydon and Holland.1 .Toowoomba Town Hall [3] (Queensland): Toowoomba's third Town Hall opens on 12 December ۩ ˟ Australia; Or, The City of Zero: (extravaganza) Written especially for Federation by J.C. Williamson and Bernard Espinasse, the story is a fantasy set 100 years in the future - the year 2000. It premieres at Her Majesty's Theatre, Sydney, on 26 December. Australis; Or, The City of Zero (Act 1, Scene 2) From production program. Fryer Library, University of Queensland. • Henry Burton: The veteran circus proprietor dies at the Dramatic Homes, Melbourne, on 9 March. • Harry Clay: Tours Queensland with his wife, Katherine, and daughter, Essie, for Walter Bell's Boer War and London Vaudeville Company. It is to be his last for another manager. • The Dartos: French dancers Francois and Aida Darto (aka Mr and Mrs Chabre) arrived in Australia in December for what will be an 11 month tour of Australasia, initially for George Musgrove and later for Harry Rickards and P.R. Dix (New Zealand). The couple reportedly raised the bar for partner dance acts, with Aida Darto in particular stunning audiences with her flexibility and grace. -

The Salt Lake Herald

t i 1 tI I tt == THE f SALT LAKE HERALD f PWENTYSEVENTJI YEAR SALT 10 S LAKE CITY WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 1897 iIDtLa R 79 I and Attorney I P L Williams of Salt in the next race and he called out I Lake represent the receivers and At ¬ NO IMPORTANT NEWS- pended as they were only being car-¬ OF i REORGAIUZED- torney Carroll winner the bookies almosta fainted WAS A FIENDISH PLAN ried on with the WRECK FAST MAIL- of Omaha and P L Payment was refused by Walsh and understanding that Williams of Salt Lake the Union Pa ¬ the political status quo would be re- ¬ cific company later by the other but not until the spected on both sides r police had to quell an incipient riot Public feeling runs high at Cayenne CHECKED THE DAUNTLESS Now Arrival of Dan The party had about 7000 to its where the governor is blamed for not SHORT waiting credit on Palmerston which will have Dynamite Placed Under a Train- sending out a punitive expedition even Ran Into an Open Switch at ME Captain Stuart to be paid before any of the mulcted at the risk of creating another Mapa Kilgora Would Not Permit firms can call a race today if every in Jamaica Omaha Moved accident > Her thing is regular All information is J New York Feb special distributed to the books from New ROUTE AROUND THE 9A World York EARTH from Jacksonville Fla says The tug QUARTERS CORBETT- and it is thought the plunger Dauntless was caught trying to escape- FOR beat beat the book time a few minutes SCHEME HAPPILY FAILED Completion of the Russian They S Road TWO MEN WERE KILLED General Manager Bancroft to sea last -

NEWSLETTER Wednesday 22 January 2020

NEWSLETTER Wednesday 22 January 2020 Happy New Year to all our past players and officials from UPCOMING EVENTS Fitzroy, Bears, and the Brisbane Lions. 17-24 JAN: Tassie Training Camp We hope you enjoy our new-look newsletter for 2020, Various venues in Hobart designed to keep our past players and officials informed on the relevant news, events and updates from around Mon 9 MAR: VIC Family Fun Day the Club and the AFL. 9:30am - 12:30pm @ Venue TBC If you have anything you might like to include in a future Fri 19 APR: AFL CPPOA Golf Day edition, please email us at [email protected] From 8:15am @ Settlers Run Golf Club State of Origin Returns Earlier this month, the AFL announced that a landmark State of Origin match will be played to raise funds for the Australian bushfire disaster. Three players from each Club will participate in a special match that will pit Victoria’s best against a team of All Stars at Marvel Stadium on Friday February 28. All money raised will boost a Community Relief Fund set-up to help rebuild facilities ripped apart by the national crisis. CLICK HERE for more information Draftees’ History Lesson The Brisbane Lions’ four newest draftees - Keidean Coleman, Brock Smith, Deven Robertson and Jaxon Prior - took a private tour of the Historical Society Museum at Marvel Stadium earlier this month to learn more about our Club’s unique and rich history. It’s a critical part of our new players’ induction process that they understand the background of Fitzroy and the Bears, and how the two clubs merged to form the Brisbane Lions. -

Grand Finals Volume I—1897-1938

aMs Er te e rEMi eAGU ind the PBALL L Es beh FOOT Tori RIAN THE s TO of the VIC Volume II 1 939-1978 Companion volume to Grand Finals Volume I—1897-1938 Introduction by Geoff Slattery visit slatterymedia.com The Slattery Media Group 1 Albert Street, Richmond Victoria, Australia, 3121 visit slatterymedia.com Copyright © The Slattery Media Group, 2012 Images copyright © Newspix / News Ltd First published by the The Slattery Media Group, 2012 ®™ The AFL logo and competing team logos, emblems and names used are all trade marks of and used under licence from the owner, the Australian Football League, by whom all copyright and other rights of reproduction are reserved. Australian Football League, AFL House, 140 Harbour Esplanade, Docklands, Victoria, Australia, 3008. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Grand finals : the stories behind the premier teams of the Victorian Football League. Volume II, 1939-1978 / edited by Geoff Slattery. ISBN: 9781921778612 (hbk.) Subjects Victorian Football League--History. Australian football--Victoria--History. Australian football--Competitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Slattery, Geoff Dewey Number: 796.33609945 Group Publisher: Geoff Slattery Sub-editors: Bernard Slattery, Charlie Happell Statistics: Cameron Sinclair Creative Director: Guy Shield -

Liveability and the Vegetated Urban Landscape

LIVEABILITY AND THE VEGETATED URBAN LANDSCAPE An investigation of opportunities for water-related interventions to drive improved liveability in metropolitan Melbourne August 2015 LIVEABILITY AND THE VEGETATED URBAN LANDSCAPE Acknowledgements Urban Initiatives Pty Ltd., an urban design and landscape architecture practice based in Melbourne, led a consortium to undertake the project. The consultant team included: Aquatic Systems Management (whole of water cycle and stormwater management) Homewood Consulting (arboriculture, vegetation assessment) G & M Connellan Consultants (irrigation management) Van De Graaff and Associates (soil science expertise) Fifth Creek Studio (urban heat management and preventative health) Paroissien Grant and Associates (contemporary subdivisional servicing advice) Environment & Land Management Pty Ltd. (town planning, planning regulation). Urban Initiatives Project Manager: Kate Heron Urban Initiatives Pty. Ltd. would also like to acknowledge the significant contributions of David Taylor (City of Yarra, formerly DELWP), Chris Porter (DELWP), Nicky Kindler (Melbourne Water) and Andrew Brophy. Members of project Technical Working Group: Anne Barker (City West Water Ben Harries (Whittlesea CC) Caitlin Keating (MPA) – chair) Clare Lombardi & Simon Sarah Buckley & Jennifer Lee Greg Moore (University of Wilkinson (GTW & CWW) (Stonnington CC) Melbourne Mark Hammett (Moonee Jason Summers (Hume CC) Alan Watts (SEW) Valley CC) Yvonne Lynch (Melbourne Peter May (University of Kein Gan & Simon Newberry CC) Melbourne -

International Tourists: W

INTERNATIONAL TOURISTS: W WHIMSICAL WALKER [1] UK (1851-1934) British clown, acrobat, animal trainer. [Born: Thomas Henry Walker] [1904] The son of a circus advance rep, Thomas Walker was apprenticed to Pablo Fanque's circus at age eight and continued in the business for around 70 years. During his career he worked with many leading circuses, including Barnum and Bailey, and became a huge star in English pantomime as a harlequin specialist. He also travelled the world three times and toured America on at least 16 occasions. Although he toured Australia only once, arriving here in September 1904 under contract to Harry Rickards, Walker's life and aspects of his career were well-known throughout the region courtesy of regular newspaper reports. Further Reference: Walker, Whimsical. From Sawdust to Windsor Castle (1922) - available online at the Internet Archive's Open Library project [sighted 18/12/2013]. OOO Courtesy of www.fulltable.com WORLD'S ENTERTAINERS [1] aka Lee and Rial's World's Entertainers [1901-1902] In 1901 J.C. Williamson, thinking to expand his already considerable theatrical empire, contracted American actor/impersonator Henry Lee and producer/entrepreneur James G. Rial to bring a company of US vaudeville acts to Australia. The tour, produced under the auspices of Williamson, Lee and Rial, was initially managed by James H. Love (1852-1902), with Lee taking on the duties of stage director. The plan was to take the company to most of the capital cities, with the major seasons naturally being produced in Sydney and Melbourne. A number of select regional centres were also chosen for short visits, while New Zealand was also seen as a likely destination at some stage. -

Amateur Footballer Rd 1 2009

LET THE GAMES BEGIN Welcome to season 2009. While our clubs go at it for In the week before Easter, real for the first time today, many hundreds of we launched the season at administrators and volunteers at club and VAFA level the MCG. It was fitting that have been hard at work for months to ensure that this Luke Beveridge was selected year will be memorable. Already, much has happened to to make the toast to our indicate that it will be. great competition. His Nick Bourke humility in speaking to the PRESIDENT From the bushfires that ravaged Victoria in February gathering cannot hide his arose a renewed sense of community. It was gratifying success. To coach St Bede’s Mentone Tigers to flags in indeed to see the efforts of so many, in tough economic C, B and A Section in successive years is an times, in coming to the aid of the afflicted. Naturally, extraordinary feat. It has never been done before and as a community organisation with ever-extending it may not be again. tentacles, the VAFA was part of this response. I salute the years of service to our game by our three Late last month, in a long-awaited and much new VAFA life members, John Bell, Bruce Ivey and anticipated tussle, the VAFA Representative team faced Peter Rhoden off against the Eastern Football League. The event raised many thousands of dollars that will be spent to We have our own ways in the Amateurs. We foster restore the fortunes of country football clubs affected family football, with our policy of no alcohol during by the fires. -

Winter Brochure (Mar19-Oct19)

EveryoneEveryone Melbourne Park WelcomeWelcome and Street OrienteeringOrienteering Winter Series 2019 vicorienteering.asn.au WINTER 2019 PARK & STREET ORIENTEERING IN AND NEAR MELBOURNE Get some fresh air and a fresh perspective by exploring your local parks and streets with a map. Park and Street Orienteering is a fun, social way to give your body and mind a great workout. Park and Street Orienteering is enjoyed by hundreds of people of all ages and abilities, from toddlers to eighty-somethings, from elite athletes to social strollers. Be as competitive or as casual as you like. Walk or run; compete individually or in a group. All events have runners’ courses ranging from 5 to 10 km, or a 1 hour course for walkers. Events are on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays during the non daylight saving period. Arrive 30 minutes before the start time, to register and prepare. Wear some comfortable clothes and shoes, and a watch; bring a torch for night events. PLEASE PARK ON ONE SIDE OF STREETS ONLY. Entry Fees For Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Saturday Series Pay on the Day: Adults – $5.00 Juniors – $3.00 Season Tickets: Season tickets are a fantastic way to save money, along with the convenience of a single payment at the start of the season. You can pay by cash, cheque, or bank transfer. Season tickets will be on sale to club members at the first three events of each series. Costs: Monday $90 for adults, $54 for juniors Tuesday $35 for adults, $21 for juniors Wednesday $90 for adults, $54 for juniors Saturday $75 for adults, $45 for juniors • Cheques should be made out to ‘Dandenong Ranges Orienteering Club’. -

Recommendation of the Executive Director and Assessment of Cultural Heritage Significance Under Part 3 of the Heritage Act 2017

Page | 1 Recommendation of the Executive Director and assessment of cultural heritage significance under Part 3 of the Heritage Act 2017 Current Name Fitzroy Cricket Ground Grandstand Location Brunswick Street, Fitzroy North, Yarra City Council Date Registered 27 June 1990 VHR Number VHR H0751 VHR Category Registered Place Hermes Number 447 Fitzroy Cricket Ground Grandstand (February 2020) EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR RECOMMENDATION TO THE HERITAGE COUNCIL: That the Heritage Council amends the existing registration of VHR H0751 in accordance with s.62 of the Heritage Act 2017 by: 1. Including additional land under s.49(1)(d)(i) and (ii). 2. Determining categories of works or activities which may be carried out in relation to the Fitzroy Cricket Ground Grandstand for which a permit is not required (permit exemptions), under s.49(3). STEVEN AVERY Executive Director Recommendation Date: Monday 16 March 2020 Advertising Period: Friday 20 March – Monday 18 May 2020 This recommendation report has been issued by the Executive Director, Heritage Victoria under s.37 of the Heritage Act 2017. 1 Current Name: Fitzroy Cricket Ground Grandstand VHR number: VHR H0751 Hermes number: 447 Page | 2 REASONS FOR REGISTRATION IN JUNE 1990 The State-level historical and architectural cultural heritage significance of the Fitzroy Cricket Ground Grandstand was recognised in June 1990 by its inclusion in the Register of Historic Buildings (VHR H0751). The registration recognised the place’s historical significance as an early surviving grandstand with associations with the development of cricket and Australian Rules football in metropolitan Melbourne. It also recognised its architectural significance as a fine example of a nineteenth-century timber grandstand.