Memorializing Other Prominent Citizens, Especially Monarchs. in the Context of the “Edinburgh” Gardens, Named in Honour of the Royal Heir, It Is Even More Significant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Entire Document

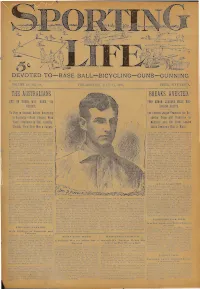

DEVOTED TO BASE BALL BICYCLING GUNS VOLUME 29, NO. 18. PHILADELPHIA, JULY 24, 1897. PRICE, FIVE CENTS. BREAKS AVERTED. ARE ON THEIR WAY HOME YIA TWO MINOR LEAGUES MAKE MID- EUROPE. SEASON SHIFTS, To Play in England Before Returning The Eastern League Transfers the Ro to Australia Much Pleased With chester Team and Franchise to Their Treatment in This Country, Montreal and the Texas League Though Their Trip Was a Failure, Shifts Denison©s Clnl) to Waco, Thirteen members of the Australian base For the first time in years a mid-season ball team sailed ou the 15th inst. from New change has been made in the Eastern York ou the American liner "St. Paul" for League circuit. Some time ago a stock England. Those in the party were: Man company was organized in Montreal by Mr. ager Harry Musgrove, Charles Over, Charles W. H. Rowe, with ample capital, with a Kemp, Walter G. Ingleton, Harry S. Irwin, view to purchasing an Eastern League fran Peter A. McAllister, Rue Ewers, Arthur chise. Efforts were made to buy either tlie K. Wiseman, Alfred S. Carter, J. H. Stuck- "Wilkesbarre or Kochester Clubs, both of ey, John Wallace and Frank Saver. which were believed to be in distress. The MU SGKOVE© S PLANS. former, however, was braced up and "We shall carry out our original inten will play out the season. Rochester tion ,of a trip around the world," said Mr. was on the fence regarding the Musgrove. ©-We shall probably play some proposition made when fate stepped in and de games in London and other parts of iCngland cided the question. -

Variety Timeline: 1900-1999

AUSTRALIAN VARIETY AND POPULAR CULTURE ENTERTAINMENT: TIMELINE 1900-1999 Symbols Theatres ˟ Works (stage, film and music) ₪ Industry issues • People, troupes and acts ۩ ₣ Film 1900 ₪ Cato and Co: Herbert Cato sets up his own theatrical agency in Sydney. Tivoli Theatre [1] (Adelaide): Harry Rickards converts the Bijou Theatre into the Tivoli. It opens on 20 June ۩ with a company that includes Pope and Sayles, Prof Fred Davys and his Giant Marionettes, Neva Carr-Glynn and Adson, Craydon and Holland.1 .Toowoomba Town Hall [3] (Queensland): Toowoomba's third Town Hall opens on 12 December ۩ ˟ Australia; Or, The City of Zero: (extravaganza) Written especially for Federation by J.C. Williamson and Bernard Espinasse, the story is a fantasy set 100 years in the future - the year 2000. It premieres at Her Majesty's Theatre, Sydney, on 26 December. Australis; Or, The City of Zero (Act 1, Scene 2) From production program. Fryer Library, University of Queensland. • Henry Burton: The veteran circus proprietor dies at the Dramatic Homes, Melbourne, on 9 March. • Harry Clay: Tours Queensland with his wife, Katherine, and daughter, Essie, for Walter Bell's Boer War and London Vaudeville Company. It is to be his last for another manager. • The Dartos: French dancers Francois and Aida Darto (aka Mr and Mrs Chabre) arrived in Australia in December for what will be an 11 month tour of Australasia, initially for George Musgrove and later for Harry Rickards and P.R. Dix (New Zealand). The couple reportedly raised the bar for partner dance acts, with Aida Darto in particular stunning audiences with her flexibility and grace. -

Edinburgh Gardens Conservation Management Plan 2004

EDINBURGH GARDENS BRUNSWICK STREET NORTH FITZROY CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN EDINBURGH GARDENS BRUNSWICK STREET NORTH FITZROY CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN Prepared for The City of Yarra Allom Lovell & Associates Conservation Architects 35 Little Bourke Street Melbourne 3000 In association with John Patrick Pty Ltd 324 Victoria Street Richmond 3121 Revised January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS i LIST OF FIGURES iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii PROJECT TEAM ix 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and Brief 1 1.2 Methodology 1 1.3 Constraints and Opportunities 1 1.4 Location 2 1.5 Listings and Classification 2 1.6 Terminology 3 2.0 HISTORY 5 2.1 Introduction 5 2.2 Geomorphology 5 2.3 North Fitzroy – the development of a suburb 5 2.4 Sport as the Recreation of Gentlemen 6 2.5 The Establishment of the Reserve: 1859-1882 7 2.6 Paths, Tree Avenues and the Railway: 1883-1900 15 2.7 The Growth of Fitzroy 20 2.8 Between the Wars: 1917-1944 22 2.9 The Post-War Years: 1945-1969 27 2.10 Recent Developments: 1970-1999 31 3.0 PHYSICAL SURVEY OF HARD LANDSCAPE ELEMENTS 34 3.1 Introduction 34 3.2 Documentation 34 3.3 Levels of Significance 34 3.4 Hard Landscape Elements 35 4.0 PHYSICAL SURVEY OF SOFT LANDSCAPE ELEMENTS 77 4.1 Introduction 77 4.2 Soft Landscape Elements 77 5.0 ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 107 5.1 Assessment Criteria and Methodology 107 5.2 Comparative Analysis 107 5.3 Edinburgh Gardens – Historical and Social Significance 114 5.4 Edinburgh Gardens – Aesthetic Significance 116 5.5 Statement of Significance 117 5.5 Applicable -

The Salt Lake Herald

t i 1 tI I tt == THE f SALT LAKE HERALD f PWENTYSEVENTJI YEAR SALT 10 S LAKE CITY WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 1897 iIDtLa R 79 I and Attorney I P L Williams of Salt in the next race and he called out I Lake represent the receivers and At ¬ NO IMPORTANT NEWS- pended as they were only being car-¬ OF i REORGAIUZED- torney Carroll winner the bookies almosta fainted WAS A FIENDISH PLAN ried on with the WRECK FAST MAIL- of Omaha and P L Payment was refused by Walsh and understanding that Williams of Salt Lake the Union Pa ¬ the political status quo would be re- ¬ cific company later by the other but not until the spected on both sides r police had to quell an incipient riot Public feeling runs high at Cayenne CHECKED THE DAUNTLESS Now Arrival of Dan The party had about 7000 to its where the governor is blamed for not SHORT waiting credit on Palmerston which will have Dynamite Placed Under a Train- sending out a punitive expedition even Ran Into an Open Switch at ME Captain Stuart to be paid before any of the mulcted at the risk of creating another Mapa Kilgora Would Not Permit firms can call a race today if every in Jamaica Omaha Moved accident > Her thing is regular All information is J New York Feb special distributed to the books from New ROUTE AROUND THE 9A World York EARTH from Jacksonville Fla says The tug QUARTERS CORBETT- and it is thought the plunger Dauntless was caught trying to escape- FOR beat beat the book time a few minutes SCHEME HAPPILY FAILED Completion of the Russian They S Road TWO MEN WERE KILLED General Manager Bancroft to sea last -

International Tourists: W

INTERNATIONAL TOURISTS: W WHIMSICAL WALKER [1] UK (1851-1934) British clown, acrobat, animal trainer. [Born: Thomas Henry Walker] [1904] The son of a circus advance rep, Thomas Walker was apprenticed to Pablo Fanque's circus at age eight and continued in the business for around 70 years. During his career he worked with many leading circuses, including Barnum and Bailey, and became a huge star in English pantomime as a harlequin specialist. He also travelled the world three times and toured America on at least 16 occasions. Although he toured Australia only once, arriving here in September 1904 under contract to Harry Rickards, Walker's life and aspects of his career were well-known throughout the region courtesy of regular newspaper reports. Further Reference: Walker, Whimsical. From Sawdust to Windsor Castle (1922) - available online at the Internet Archive's Open Library project [sighted 18/12/2013]. OOO Courtesy of www.fulltable.com WORLD'S ENTERTAINERS [1] aka Lee and Rial's World's Entertainers [1901-1902] In 1901 J.C. Williamson, thinking to expand his already considerable theatrical empire, contracted American actor/impersonator Henry Lee and producer/entrepreneur James G. Rial to bring a company of US vaudeville acts to Australia. The tour, produced under the auspices of Williamson, Lee and Rial, was initially managed by James H. Love (1852-1902), with Lee taking on the duties of stage director. The plan was to take the company to most of the capital cities, with the major seasons naturally being produced in Sydney and Melbourne. A number of select regional centres were also chosen for short visits, while New Zealand was also seen as a likely destination at some stage. -

Base Ball Uniforms Cap, Shirt, Pants Stockings and Jbj?£T

TRADEMAHKED BY THE SPORTIWQ LIFE FCTB. CO. ENTERED AT PHILA. P. O. AS SECOND CLASS MATTER VOLUME -29, NO. PHILADELPHIA, APRIL 10, 1897. PRICE, FIVE CENTS. THENUTMEGLEAGUE. INTHECOALREGIOKS. THE FINISHING TOUCHES PUT TO THE ANTHRACITE LEAGUE AGAIN PUT THE ORGANIZATION. IN THE FIELD. The Veteran Jack Chapman Secures the Six Towns fill Have a Championship Meriden Franchise Jim O©Rourke, Season Among Themselves A Pre Jerry Denny and Jack Piggott Also liminary Organization Formed at Figure Among the Magnates. Hazleton. Derby, April 5. Editor "Sporting Life:" Hazleton, Pa., April 6. Editor "Sporting --The new Connecticut State Base Ball Life:" A meeting of the representatives Leogue, which is composed of Bridgeport- of the Anthracite Base Ball League was Meriden, Waterbury. Derby. Torrington and held here Sunday afternoon, for the purpose Bristol, held its schedule meeting Saturday PITCHER STEPHEN ASHB, of reorganization and the arrangement of here. The season will be from May 1 to a schedule. Tn the absence of President September 15. The League will lie run oil strict McMonigle Charles (lallagher, of Drif- business principles, and promises to be a suc ton. was chosen chairman. The clubs cess. represented were: Hazleton, by John Sturgis Whitlock, one of the wealthiest men Turnbach and John Graff; Drif ton, by John Boner in Connecticut, is the president, and James H. and Charles Gallaguer: Lattimer, by Jacob Dough- O©Uourke, of Bridgeport, secretary and treas~ erty and Joseph Costello. Milnesville, McAdoo iirer. The directois are John Fruin, Thos. H. and Freeland, which towns were in the League Graham, James H. O©llourke, J. -

Just for Fun Rohan Storey Celebrates a Century of Seaside Excitement

The Spring–Summer 2012 journal of Vol.13 No.4 Just for fun Rohan Storey celebrates a century of seaside excitement. n the night of the 13 December on the River Caves, the thrill of the Big Luna Park was aimed squarely 1912, the gates of Melbourne’s Dipper, or the barrels and slides of the at young adults, rather than families OLuna Park opened to an Giggle Palace, all now gone. or children, opening every evening expectant throng, drawn by extensive But what was it like 100 years ago? throughout the summer season, when the advertising and the sparkle of 30 000 tiny …The outside was exactly as it is today, thousands of globes created a magical electric globes. It was a triumph; crowds with the face, towers, and the framework fairyland. Children were not left out – had to be turned away, and the Park has of the scenic railway wrapping around the special weekend ‘matinée’ afternoon drawn crowds ever since. site, enclosing a fantasyland inside. But openings allowed all ages to enjoy the That mad huge face on the St Kilda the inside was quite different in the years Park together. foreshore, housed between towers topped before WWI. Instead of many mechanical Many of the attractions involved thrills by pavilions like something from the rides, there were attractions and sideshows and wonder, as well as the chance to be Arabian Nights, has been a familiar lining the perimeter, leaving an open with members of the opposite sex, in a landmark on the St Kilda landscape to central space which was dominated by a place somehow removed from everyday generations of Melbournians. -

Variety Timeline 1900-1999

AUSTRALIAN VARIETY AND POPULAR CULTURE ENTERTAINMENT: TIMELINE 1900-1999 Symbols Theatres ˟ Works (stage, film and music) ₪ Industry issues • People, troupes and acts ۩ ₣ Film 1900 ₪ Cato and Co: Herbert Cato sets up his own theatrical agency in Sydney. Tivoli Theatre [1] (Adelaide): Harry Rickards converts the Bijou Theatre into the Tivoli. It opens on 20 June ۩ with a company that includes Pope and Sayles, Prof Fred Davys and his Giant Marionettes, Neva Carr-Glynn and Adson, Craydon and Holland.1 .Toowoomba Town Hall [3] (Queensland): Toowoomba's third Town Hall opens on 12 December ۩ ˟ Australia; Or, The City of Zero: (extravaganza) Written especially for Federation by J.C. Williamson and Bernard Espinasse, the story is a fantasy set 100 years in the future - the year 2000. It premieres at Her Majesty's Theatre, Sydney, on 26 December. Australis; Or, The City of Zero (Act 1, Scene 2) From production program. Fryer Library, University of Queensland. • T.C. Ambrose: Baritone/actor. A ten-year veteran of the Royal Comic Opera Company (ca. 1887-1897), and occasional entertainer at variety establishments, Thomas Ambrose dies in Sydney's St Vincent's Hospital on 30 November from an as yet unestablished cause. • Henry Burton: The veteran circus proprietor dies at the Dramatic Homes, Melbourne, on 9 March. • Harry Clay: Tours Queensland with his wife, Katherine, and daughter, Essie, for Walter Bell's Boer War and London Vaudeville Company. It is to be his last for another manager. • The Dartos: French dancers Francois and Aida Darto (aka Mr and Mrs Chabre) arrived in Australia in December for what will be an 11 month tour of Australasia, initially for George Musgrove and later for Harry Rickards and P.R. -

![[1920-1935] and Bibliography](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4205/1920-1935-and-bibliography-12914205.webp)

[1920-1935] and Bibliography

1920 OH YOU BABY DOLL: [musical playlet] Txt/Mus. [n/e] 1919: Palace Gardens (Bris); 2-8 Jan. - Dir/Mngr. Carlton Max; M Dir. Eric John. - Troupe: Follies Costume Comedy Company. - Cast incl. Carlton Max, Bert Dudley, Evelyn Dudley, Will Rollow, Myrtle Charleton, Lilla Spear, Harry Marshall. THE GENERAL AND HIS ARMY: [revusical] Txt. Walter Johnson; Mus. [n/e] Described in advertising as an Eastern comedy. 1920: Cremorne Theatre (Bris); 10-16 Jan. - Dir. Walter Johnson; Prod/Prop. John N. McCallum (Dandies Qld); M Dir. Fred Whaite; Cost. Mary Glynn. - Troupe: Walter Johnson's Town Topics. - Cast incl. Elton Black, Yorke Gray, Alice Bennetto, Belle Millette, Lou Vernon, Leslie Jephcott, Gladys Raines. TOO MANY WIVES: [revusical] Txt. Harry Burgess; Mus. [n/e]. This revusical deals with the plight of Izzy Getz, who has promised to marry half a dozen women, and is plunged into despair when they all, believing him to be the owner of some prosperous oil wells, appear to claim the fulfilment of this promise. Songs incorporated into the 1920 Fuller's Theatre season included: "When I was a Dreamer" (sung by Ernest Lashbrooke), "Somebody Knows" (Lydia Carne) and "Peaches Down in Georgia" (Hilda Cripps). 1920: Fullers Theatre (Syd); 17-23 Jan. - Dir. Harry Burgess; Prod. Fullers' Theatres Ltd. - Troupe: Harry Burgess Revue Company. - Cast incl. Gus Franks (Izzy Getz), Harry Burgess, Les Warton, Ernest Crawford, Ernest Lashbrooke, Lola Hunt, Florrie Horan, Lydia Carne, Hilda Cripps, Annie Douglas, plus chorus and ballet. "Fuller's Theatre." SMH: 19 Jan. (1920), 9. 2 PEAS IN A POD: [revusical] Txt. Al Bruce; Mus. -

The Capitol: Its Producer, Director, Auteurs and Given Circumstances

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1998 The aC pitol: its producer, director, auteurs and given circumstances : an epic of a "lucky" theatre Lynne Dent University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Dent, Lynne, The aC pitol: its producer, director, auteurs and given circumstances : an epic of a "lucky" theatre, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, , University of Wollongong, 1998. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2114 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. The Capitol: Its Producer, Director, Auteurs and Given Circumstances: An epic of a "lucky" theatre. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree MA (HONS) from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by LYNNE DENT BA (HONS) FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1998 Abstract Sydney's Capitol theatre stands on the oldest site on which there has been theatrical activity. It is significant for its historic architecture, distinctive interior and place in popular entertainment. Using a theatre-based analogy, this study sought to explore the history of the site, building and theatres focussing on the involvement of the City Council, Chief Secretary's Department and its Lessees, from the height of its popularity to its loss of public favour and through changing circumstances. Research was undertaken in the archives of Sydney City Council, Department of Local Government and Cooperatives and National Trust of Australia, as well as newspaper sources held by many libraries. Secondary sources included texts of authorities in the areas of architecture, theatre, cinema, related government legislation and publications of the Australian Theatre Historical Society (now the Australian Cinema and Theatre Society). -

La Mama Down but Not Out…Yet Is It Almost Curtains for Melbourne’S—And Australia’S—Iconic Theatre Incubator?

ON STAGE The Summer 2007 newsletter of Vol.8 No.1 La Mama down but not out…yet Is it almost curtains for Melbourne’s—and Australia’s—iconic theatre incubator? ronically, the recent revelation that La about $34 000 a year. VicHealth has also ‘Every theatre—from the MTC down—is Mama had lost its triennial Australia extended its audience access grant of worried about its budget, but the present ICouncil Theatre Board grant and been $60 000 annually to the end of 2008. tight times particularly affect smaller told its future funding was not guaranteed, The Age’s Arts writer Alison Croggan companies, which are the engines of came at the same time as an announcement pointed out that the Theatre Board is innovation in any culture.’ that the Victorian Government has increased searching for ways to stretch an increasingly Melbourne University senior theatre its annual grant to what it described as ‘this tight budget across an increasingly active lecturer Denise Varney described the * crucible of Australian theatre’ by 20 per cent theatre sector. ‘Arts —up $35 000 to $200 000. funding is not The bewildered La Mama artistic indexed, and this director Liz Jones told The Age: ‘They were means that the virtually the same submissions, but they led average grant for a to very different conclusions. Arts Victoria small-to-medium was as taken aback as I was at the Australia company has, in real Council’s decision.’ terms, fallen by 24 Jones said the Theatre Board had two per cent since 1998. complaints—that La Mama’s submission was ‘Melbourne is not ‘strategically relevant’ and that the experiencing a theatre company’s reserves were too low.