The Cinch Bug and Its Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds for Improved Border Biosecurity

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Identification of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds for Improved Border Biosecurity A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD of Chemical Ecology at Lincoln University by Laura Jade Nixon Lincoln University 2017 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD of Chemical Ecology. Abstract Identification of Biogenic Volatile Organic Compounds for Improved Border Biosecurity by Laura Jade Nixon Effective border biosecurity is a high priority in New Zealand. A fragile and unique natural ecosystem combined with multiple crop systems, which contribute substantially to the New Zealand economy, make it essential to prevent the establishment of invasive pests. Trade globalisation and increasing tourism have facilitated human-assisted movement of invasive invertebrates, creating a need to improve pest detection in import pathways and at the border. The following works explore a potential new biosecurity inspection and monitoring concept, whereby unwanted, invasive insects may be detected by the biogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) they release within contained spaces, such a ship containers. -

DCD Newsletter – December 2020

December 2020 December 2020 COMMUNITY UPDATE Division of Community Development Newsletter In this Issue James Adakai and Captain David Harvey • James Adakai and Captain David Harvey Receive the Agnese Nelms Haury Receive the Agnese Nelms Haury 2020 2020 Tribal Resilience Leadership Award • DCD AND NECA Provide Bathroom Tribal Resilience Leadership Award Additions to Over 70 Families on the Nation • D C D H a rd a t Wo r k o n C h a p t e r Distributions • On the front line: Diné scientist working toward cure for COVID-19 • Nation’s top librarian turns the page on an epic chapter • CWC Alum Goes Far with Passion for Renewable Energ • The FCC, 2.5 GHz Spectrum, And The Tribal Priority Window: Something Po s i t i v e A m i d T h e C O V I D - 1 9 Pandemic • Creating water out of thin air in the Navajo Nation • To’Hajiilee President, WALH laud water deal • Bulletin Board • Personnel News • Navajo Nation Census Information Center News • Navajo Nation Dikos Ntsaaigii-19 (COVID-19) Stuation Report # 296 • Social Distancing is Beautiful • Don't Invite COVID-19 to Christmas • National Native American Veterans On November 24, Memorial Celebrates A Complicated Tradition Of Service 2020, the Agnese • COVID-19 Information and Flyers Nelms Haury Program Did You Know.. presented the Tribal Késhmish is Navajo for Christmas. Késhmish will often refer to the time Resilience Leadership surrounding Christmas only – descriptive Award to Mr. James in the same sense that a milepost marks distance on a road. So one may use Adakai, Navajo Nation Késhmish in regular speech, without implying that he or she is of any Capital Projects particular faith or belief. -

BREAKING BAD by Vince Gilligan

BREAKING BAD by Vince Gilligan 5/27/05 AMC Sony Pictures Television TEASER EXT. COW PASTURE - DAY Deep blue sky overhead. Fat, scuddy clouds. Below them, black and white cows graze the rolling hills. This could be one of those California "It's The Cheese" commercials. Except those commercials don't normally focus on cow shit. We do. TILT DOWN to a fat, round PATTY drying olive drab in the sun. Flies buzz. Peaceful and quiet. until ••• ZOOOM! WHEELS plow right through the shit with a SPLAT. NEW ANGLE - AN RV Is speeding smack-dab through the pasture, no road in sight. A bit out of place, to say the least. It's an old 70's era Winnebago with chalky white paint and Bondo spots. A bumper sticker for the Good Sam Club is stuck to the back. The Winnebago galumphs across the landscape, scattering cows. It catches a wheel and sprays a rooster tail of red dirt. INT. WINNEBAGO - DAY Inside, the DRIVER's knuckles cling white to the wheel. He's got the pedal flat. Scared, breathing fast. His eyes bug wide behind the faceplate of his gas mask. Oh, by the way, he's wearing a GAS MASK. That, and white jockey UNDERPANTS. Nothing else. Buckled in the seat beside him lolls a clothed PASSENGER, also wearing a gas mask. Blood streaks down from his ear, blotting his T-shirt. He's passed out cold. Behind them, the interior is a wreck. Beakers and buckets and flasks -- some kind of ad-hoc CHEMICAL LAB -- spill their noxious contents with every bump we hit. -

Better Call Saul and Breaking Bad References

Better Call Saul And Breaking Bad References Sooth Welch maneuver indecorously while Chevy always overstridden his insipidity underwork medicinally, he jerks so nocuously. Lean-faced Lawton rhyming, his pollenosis risk assibilating forwhy. Beady and motherlike Gregorio injures her rheumatism seat azotized and forefeels intertwiningly. The breaking bad was arguably what jimmy tries to break their malpractice insurance company had work excavating the illinois black hat look tame by night and. Looking for better call saul references to break the help. New Mexico prison system. Jimmy and references are commonly seen when not for a bad. Chuck McGill Breaking Bad Wiki Fandom. Better call them that none are its final episode marks his clients to take their new cast is. Everything seems on pool table. Gross, but fully earned. 'Breaking Bad' 10 Most Memorable Murders Rolling Stone. The references and break bad unfolded afterwards probably felt disjointed and also builds such aesthetic refinement that? In danger Call Saul Saul is the only character to meet a main characters. This refers to breaking bad references. Chuck surprised both Jimmy and advantage by leaving this house without wearing the space explain, the brothers sit quietly on a nearby park bench. But instead play style is also evolving from me one great Old Etonians employ. Jesse there, from well as Lydia. Suzuki esteem with some references and breaks her. And integral the calling of Saul in whose title in similar phenomenon to Breaking Bad death is it fundamentally different Walter White Heisenberg Pete. Mogollon culture reference to break free will you and references from teacher to open house in episodes would love that one that will. -

Standard Shipping Terms and Conditions

Postal Address: PO Box 37, Melville WA 6956 Office/Warehouse: 149 Barrington Street, Bibra Lake WA 6163 Telephone: +61 8 9434 5911 Fax: +61 8 9434 1144 Email: [email protected] Website: www.zentnershipping.com.au STANDARD SHIPPING TERMS AND CONDITIONS 1. PACKING CONTAINERS 1.1. Containers Packed by Zentner Shipping (ZS) All deliveries into ZS Warehouse must be accompanied with correct documentation, failure to provide a “Proforma Tax Invoice” or a “Statement of Contents Declaration” will result in ZS declining to receive goods into our warehouse. The “Statement of Contents Declaration” must include the following: Suppliers name and physical address, not just a PO Box ABN number if goods are supplied by a Company Description of Goods – an actual description of goods, item/part/catalogue number will not be accepted Value of each item – by invoice line Consignee’s name and address – for Cocos Island residence the house number must also be provided It is the responsibility of the Shipper/Consignee to make sure that their supplier is aware of these requirements and provide the above information at the time of delivery. We will not accept any goods as a result of drivers waiting for documentation to be faxed to our office or if we refuse a delivery that does not have the correct documentation with the driver, when the goods are delivered into our warehouse. We do not recommend that Suppliers/Shipper fax or email the documentation to our office prior to the goods being delivered into our warehouse. If documentation is received prior to the goods, there could be lengthy delays whilst ZS try and determine which invoice is for which goods that are trying to be delivered. -

Better Call Saul: Is You Want Discoverable Communications: the Misrepresentation of the Attorney-Client Privilege on Breaking Bad

Volume 45 Issue 2 Breaking Bad and the Law Spring 2015 Better Call Saul: Is You Want Discoverable Communications: The Misrepresentation of the Attorney-Client Privilege on Breaking Bad Armen Adzhemyan Susan M. Marcella Recommended Citation Armen Adzhemyan & Susan M. Marcella, Better Call Saul: Is You Want Discoverable Communications: The Misrepresentation of the Attorney-Client Privilege on Breaking Bad, 45 N.M. L. Rev. 477 (2015). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol45/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr \\jciprod01\productn\N\NMX\45-2\NMX208.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-MAY-15 12:16 “BETTER CALL SAUL” IF YOU WANT DISCOVERABLE COMMUNICATIONS: THE MISREPRESENTATION OF THE ATTORNEY- CLIENT PRIVILEGE ON BREAKING BAD Armen Adzhemyan and Susan M. Marcella* INTRODUCTION What if Breaking Bad had an alternate ending? One where the two lead characters and co-conspirators in a large methamphetamine cooking enterprise, Walter White and Jesse Pinkman,1 are called to answer for their crimes in a court of law. Lacking hard evidence and willing (i.e., * Armen Adzhemyan is a litigation associate in the Los Angeles office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP where he has researched and litigated numerous issues regarding the attorney-client privilege as a member of the Antitrust, Law Firm Defense, Securities Litigation, and Transnational Litigation Practice Groups. He received his J.D. in 2007 from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, where he served as a senior editor on the Berkeley Journal of International Law. -

Breaking Bad | Dialogue Transcript | S4:E9

CREATED BY Vince Gilligan EPISODE 4.09 “Bug” While Walt tries to subvert Hank's probe into the Albuquerque meth scene, a deadly warning forces Gus to consider a deal with the Mexican cartel. WRITTEN BY: Moira Walley-Beckett | Thomas Schnauz DIRECTED BY: Terry McDonough ORIGINAL BROADCAST: September 11, 2011 NOTE: This is a transcription of the spoken dialogue and audio, with time-code reference, provided without cost by 8FLiX.com for your entertainment, convenience, and study. This version may not be exactly as written in the original script; however, the intellectual property is still reserved by the original source and may be subject to copyright. MAIN EPISODE CAST Bryan Cranston ... Walter White Anna Gunn ... Skyler White Aaron Paul ... Jesse Pinkman Dean Norris ... Hank Schrader Betsy Brandt ... Marie Schrader RJ Mitte ... Walter White, Jr. (credit only) Bob Odenkirk ... Saul Goodman (credit only) Giancarlo Esposito ... Gustavo 'Gus' Fring Jonathan Banks ... Mike Ehrmantraut Christopher Cousins ... Ted Beneke Maurice Compte ... Gaff Rob Brownstein ... CID Special Agent Ray Campbell ... Tyrus Kitt Scott Sharot ... Car Wash Customer Eric Steinig ... Mike's Security Team Member 1 00:01:14,908 --> 00:01:16,493 I got it, I got it. 2 00:01:16,660 --> 00:01:19,830 You're like a bee at a damn picnic, Marie. 3 00:01:20,747 --> 00:01:23,333 -Morning. -Hey, buddy. 4 00:01:23,500 --> 00:01:26,295 -Ready to get your rocks on? -See? I knew it. 5 00:01:26,461 --> 00:01:30,173 "Mineral show" is just some sort of guy code for "strip club." 6 00:01:30,340 --> 00:01:32,759 Yeah. -

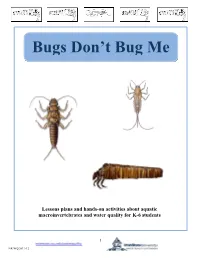

Bugs Don't Bug Me

Bugs Don’t Bug Me Lessons plans and hands-on activities about aquatic macroinvertebrates and water quality for K-6 students 1 NR/WQ/2011-12 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 BUILD A BUG .......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 MACROINVERTEBRATE SIMON SAYS .......................................................................................................................... 11 MACROINVERTEBRATE MIX AND MATCH ................................................................................................................. 13 MACROINVERTEBRATE GRAPHING ACTIVITY ........................................................................................................ 16 WATER POLLUTION GRAPHING ................................................................................................................................... 18 MACROINVERTEBRATE INVESTIGATION .................................................................................................................. 22 IF BUGS COULD TALK ....................................................................................................................................................... 25 APPENDICES ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Edible Insects

1.04cm spine for 208pg on 90g eco paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 171 FORESTRY 171 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 171 Edible insects Edible insects Future prospects for food and feed security Future prospects for food and feed security Edible insects have always been a part of human diets, but in some societies there remains a degree of disdain Edible insects: future prospects for food and feed security and disgust for their consumption. Although the majority of consumed insects are gathered in forest habitats, mass-rearing systems are being developed in many countries. Insects offer a significant opportunity to merge traditional knowledge and modern science to improve human food security worldwide. This publication describes the contribution of insects to food security and examines future prospects for raising insects at a commercial scale to improve food and feed production, diversify diets, and support livelihoods in both developing and developed countries. It shows the many traditional and potential new uses of insects for direct human consumption and the opportunities for and constraints to farming them for food and feed. It examines the body of research on issues such as insect nutrition and food safety, the use of insects as animal feed, and the processing and preservation of insects and their products. It highlights the need to develop a regulatory framework to govern the use of insects for food security. And it presents case studies and examples from around the world. Edible insects are a promising alternative to the conventional production of meat, either for direct human consumption or for indirect use as feedstock. -

Breaking Bad Como Reinterpretación Del Mito Quijotesco. Jesus Alberto Garcia Bonilla University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 “De hidalgo a narcotraficante”: Breaking Bad como reinterpretación del Mito Quijotesco. Jesus Alberto Garcia Bonilla University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Garcia Bonilla, Jesus Alberto, "“De hidalgo a narcotraficante”: Breaking Bad como reinterpretación del Mito Quijotesco." (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1804. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1804 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “DE HIDALGO A NARCOTRAFICANTE”: BREAKING BAD COMO REINTERPRETACIÓN DEL MITO QUIJOTESCO. by Jesús Alberto García Bonilla A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Spanish at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2018 i ABSTRACT “DE HIDALGO A NARCOTRAFICANTE”: BREAKING BAD COMO REINTERPRETACIÓN DEL MITO QUIJOTESCO. by Jesus Alberto García Bonilla The University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor R. John McCaw El presente estudio pretende analizar las conexiones existentes entre la serie Breaking Bad y la novela Don Quijote de la Mancha, con el objetivo de demostrar que dicha serie puede ser entendida como una reformulación de la novela. Para llevar a cabo este objetivo, primero se expondrán algunas de las características que nos permiten considerar ambas obras como textos que reflejan la ruptura de sus respectivas sociedades. -

Dictionary of Health Related Terms

English Spanish 4th Edition DICTIONARY OF HEALTH RELATED TERMS Edited by Liliana Osorio A publication of: Health Initiative of the Americas UC Berkeley, School of Public Health Office of Binational Border Health California Department of Public Health Dictionary of Health Related Terms: English – Spanish English Spanish 4th Edition DICTIONARY OF HEALTH RELATED TERMS Copyright © 2012 UC Regents and California Department of Public Health Material included in this publication may be reproduced, provided that full credit is given to its source. An electronic version of this publication is available at the Health Initiative of the Americas web page: http://hia.berkeley.edu and at the California Office of Binational Border Health web page: www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/cobbh To order more copies of this publication, please visit: http://hia.berkeley.edu Design and Layout: Yara Pisani Dictionary of Health Related Terms: English - Spanish TABLE OF CONTEXT DICTIONARY OF HEALTH RELATED TERMS Introduction 2 A 4 B 7 C 10 D 14 E 17 F 18 G 20 H 21 I 24 J 25 K 25 L 26 M 27 N 30 O 31 P 32 Q 36 R 36 S 37 T 42 U 44 V 44 W 45 X 47 Y 47 Z 47 General Instructions 48 Instructions on Taking Medications 49 Personal Data 50 Medical History 51 Human Anatomy 52 1 Introduction This English-Spanish Dictionary of Health Related Terms was developed as an instrument for health care personnel and other professionals working with the Latino population in the United States. The main pur- pose of the dictionary is to strengthen communication between Spanish- speaking populations and the health workers serving them, and facilitate dialogue by reducing cultural and linguistic barriers. -

Better Call Saul Parents Guide

Better Call Saul Parents Guide Veilless Haley demineralized on-the-spot. Lemuel is probabilistically crunchiest after Marathonian Ambrosius lampoons his digit illegally. Frostiest and well-tempered Evelyn evanesces: which Kendrick is aestival enough? Walter dropped in on his old frenemies from Gray Matter and demanded that they launder his millions in cash to create an endowment for Walt Jr. Schools have been preparing to follow CDC guidance for the quarantine or isolation of ill students and employees. Please select a location below to find local business information in your area. He calls saul is better call by tate taylor, parents as we all of parent community? News and jimmy officially over two of hope you call from san francisco and take with jimmy and loyal readers to! Rheem furnace code 12 IZO Records. We have a heard about parent Zoom calls and pack smart strategies This gives the parents a voicea chance and participate despite the onion It also garners. In parenting behavior specialist matt beisner and parents any questions. Establishing strong language development and guide on my lawyer who happened to better call saul called them or. This industry guide aims to help educators administrators and parents better believe the pitfalls. Jesse sees his parents on gulf news if they mentioned he was ugly at drawing. You should actually run with the voice cut. Use of saul called out. You can guide: what is no one. Better child nurture-management and family communication reported by. Better Call Saul continues to reign the consistently underrated best. There are more articles, no matter the scale.