Justice and Non-Human Animals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foucault and Animals

Foucault and Animals Edited by Matthew Chrulew, Curtin University Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel, The University of Sydney LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Foreword vii List of Contributors viii Editors’ Introduction: Foucault and Animals 1 Matthew Chrulew and Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel PART 1 Discourse and Madness 1 Terminal Truths: Foucault’s Animals and the Mask of the Beast 19 Joseph Pugliese 2 Chinese Dogs and French Scapegoats: An Essay in Zoonomastics 37 Claire Huot 3 Violence and Animality: An Investigation of Absolute Freedom in Foucault’s History of Madness 59 Leonard Lawlor 4 The Order of Things: The Human Sciences are the Event of Animality 87 Saïd Chebili (Translated by Matthew Chrulew and Jefffrey Bussolini) PART 2 Power and Discipline 5 “Taming the Wild Profusion of Existing Things”? A Study of Foucault, Power, and Human/Animal Relationships 107 Clare Palmer 6 Dressage: Training the Equine Body 132 Natalie Corinne Hansen For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV vi CONTENTS 7 Foucault’s Menagerie: Cock Fighting, Bear Baiting, and the Genealogy of Human-Animal Power 161 Alex Mackintosh PART 3 Science and Biopolitics 8 The Birth of the Laboratory Animal: Biopolitics, Animal Experimentation, and Animal Wellbeing 193 Robert G. W. Kirk 9 Animals as Biopolitical Subjects 222 Matthew Chrulew 10 Biopower, Heterogeneous Biosocial Collectivities and Domestic Livestock Breeding 239 Lewis Holloway and Carol Morris PART 4 Government and Ethics 11 Apum Ordines: Of Bees and Government 263 Craig McFarlane 12 Animal Friendship as a Way of Life: Sexuality, Petting and Interspecies Companionship 286 Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel 13 Foucault and the Ethics of Eating 317 Chloë Taylor Afterword 339 Paul Patton Index 345 For use by the Author only | © 2017 Koninklijke Brill NV CHAPTER 8 The Birth of the Laboratory Animal: Biopolitics, Animal Experimentation, and Animal Wellbeing Robert G. -

It's a (Two-)Culture Thing: the Laterial Shift to Liberation

Animal Issues, Vol 4, No. 1, 2000 It's a (Two-)Culture Thing: The Lateral Shift to Liberation Barry Kew rom an acute and, some will argue, a harsh, a harsh, fantastic or even tactically naive F naive perspective, this article examines examines animal liberation, vegetarianism vegetarianism and veganism in relation to a bloodless culture ideal. It suggests that the movement's repeated anomalies, denial of heritage, privileging of vegetarianism, and other concessions to bloody culture, restrict rather than liberate the full subversionary and revelatory potential of liberationist discourse, and with representation and strategy implications. ‘Only the profoundest cultural needs … initially caused adult man [sic] to continue to drink cow milk through life’.1 In The Social Construction of Nature, Klaus Eder develops a useful concept of two cultures - the bloody and the bloodless. He understands the ambivalence of modernity and the relationship to nature as resulting from the perpetuation of a precarious equilibrium between the ‘bloodless’ tradition from within Judaism and the ‘bloody’ tradition of ancient Greece. In Genesis, killing entered the world after the fall from grace and initiated a complex and hierarchically-patterned system of food taboos regulating distance between nature and culture. But, for Eder, it is in Israel that the reverse process also begins, in the taboo on killing. This ‘civilizing’ process replaces the prevalent ancient world practice of 1 Calvin. W. Schwabe, ‘Animals in the Ancient World’ in Aubrey Manning and James Serpell, (eds), Animals and Human Society: Changing Perspectives (Routledge, London, 1994), p.54. 1 Animal Issues, Vol 4, No. 1, 2000 human sacrifice by animal sacrifice, this by sacrifices of the field, and these by money paid to the sacrificial priests.2 Modern society retains only a very broken connection to the Jewish tradition of the bloodless sacrifice. -

Liberation Survives Early Criticism and Is Pivotal to Public Health

Deckers J. Why "Animal (De)liberation" survives early criticism and is pivotal to public health. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 2017, 23(5), 1105-1112. Copyright: © 2017 The Authors. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12807 Date deposited: 02/10/2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Received: 3 April 2017 Revised: 23 June 2017 Accepted: 27 June 2017 DOI: 10.1111/jep.12807 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Why “Animal (De)liberation” survives early criticism and is pivotal to public health Jan Deckers PhD1 1 Senior Lecturer in Health Care Ethics, School of Medical Education, Newcastle University, Summary Newcastle upon Tyne, UK In 2016, the book Animal (De)liberation: Should the Consumption of Animal Products Be Banned? was published. This article aims to engage with the critique that this book has received and to Correspondence clarify and reinforce its importance for human health. It is argued that the ideas developed in the Jan Deckers, Newcastle University School of book withstand critical scrutiny. As qualified moral veganism avoids the pitfalls of other moral Medical Education, Ridley 1 Building positions on human diets, public health policies must be altered accordingly, subject to adequate Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK. Email: [email protected] political support for its associated vegan project. -

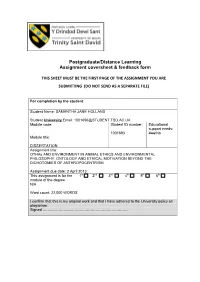

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment Coversheet & Feedback Form

Postgraduate/Distance Learning Assignment coversheet & feedback form THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by the student: Student Name: SAMANTHA JANE HOLLAND Student University Email: [email protected] Module code: Student ID number: Educational support needs: 1001693 Yes/No Module title: DISSERTATION Assignment title: OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Assignment due date: 2 April 2013 This assignment is for the 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th module of the degree N/A Word count: 22,000 WORDS I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed …………………………………………………………… Assignment Mark 1st Marker’s Provisional mark 2nd Marker’s/Moderator’s provisional mark External Examiner’s mark (if relevant) Final Mark NB. All marks are provisional until confirmed by the Final Examination Board. For completion by Marker 1 : Comments: Marker’s signature: Date: For completion by Marker 2/Moderator: Comments: Marker’s Signature: Date: External Examiner’s comments (if relevant) External Examiner’s Signature: Date: ii OTHAs AND ENVIRONMENT IN ANIMAL ETHICS AND ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY: ONTOLOGY AND ETHICAL MOTIVATION BEYOND THE DICHOTOMIES OF ANTHROPOCENTRISM Samantha Jane Holland March 2013 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Nature University of Wales, Trinity Saint David Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

Submission for the Inquiry Into the Impact of Animal Rights Activism on Victorian Agriculture

AA SUBMISSION 340 Submission for the Inquiry into the Impact of Animal Rights Activism on Victorian Agriculture 1. Term of reference a. the type and prevalence of unauthorised activity on Victorian farms and related industries, and the application of existing legislation: In Victoria, animal cruelty – including, but not limited to, legalised cruelty – neglect and violations of animal protection laws are a reality of factory farming. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986 (Vic) affords little protection to farm animals for a number of reasons, including the operation of Codes of Practice and the Livestock Management Act 2010 (Vic). The fact that farm animals do not have the same protection as companion animals justifies applying a regime of institutionalised and systematic cruelty to them every single day of their lives: see, for example, the undercover footage contained on Aussie Farms, ‘Australian Pig Farming: The Inside Story’ (2015) < http://www.aussiepigs.com.au/ >. It is deeply concerning and disturbing that in addition to the legalised cruelty farm animals are subjected to, farm animals are also subjected to illegal/unauthorised cruelty on Victorian farms. The type of unauthorised activity on Victorian farms is extremely heinous: this is evidenced by the fact that it transcends the systematic cruelty currently condoned by law and the fact that footage of incidences of such unauthorised activity is always horrific and condemned by the public at large. Indeed, speaking about footage of chickens being abused at Bridgewater Poultry earlier this year, even the Victorian Farmers Federation egg group president, Tony Nesci, told the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age that he was horrified by the footage and livid at what had happened. -

Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements

Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 5 2016 Free Tilly?: Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements Becky Boyle Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijlse Part of the Law Commons Publication Citation Becky Boyle, Free Tilly?: Legal Personhood for Animals and the Intersectionality of the Civil & Animal Rights Movements, 4 Ind. J. L. & Soc. Equality 169 (2016). This Student Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indiana Journal of Law and Social Equality Volume 4, Issue 2 FREE TILLY?: LEGAL PERSONHOOD FOR ANIMALS AND THE INTERSECTIONALITY OF THE CIVIL & ANIMAL RIGHTS MOVEMENTS BECKY BOYLE INTRODUCTION In February 2012, the District Court for the Southern District of California heard Tilikum v. Sea World, a landmark case for animal legal defense.1 The organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) filed a suit as next friends2 of five orca whales demanding their freedom from the marine wildlife entertainment park known as SeaWorld.3 The plaintiffs—Tilikum, Katina, Corky, Kasatka, and Ulises—were wild born and captured to perform at SeaWorld’s Shamu Stadium.4 They sought declaratory and injunctive relief for being held by SeaWorld in violation of slavery and involuntary servitude provisions of the Thirteenth Amendment.5 It was the first court in U.S. -

The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap

bs_bs_banner Journal of Applied Philosophy,Vol.31, No. 2, 2014 doi: 10.1111/japp.12051 The Scope of the Argument from Species Overlap OSCAR HORTA ABSTRACT The argument from species overlap has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics and speciesism. However, there has been much confusion regarding what the argument proves and what it does not prove, and regarding the views it challenges.This article intends to clarify these confusions, and to show that the name most often used for this argument (‘the argument from marginal cases’) reflects and reinforces these misunderstandings.The article claims that the argument questions not only those defences of anthropocentrism that appeal to capacities believed to be typically human, but also those that appeal to special relations between humans. This means the scope of the argument is far wider than has been thought thus far. Finally, the article claims that, even if the argument cannot prove by itself that we should not disregard the interests of nonhuman animals, it provides us with strong reasons to do so, since the argument does prove that no defence of anthropocentrism appealing to non-definitional and testable criteria succeeds. 1. Introduction The argument from species overlap, which has also been called — misleadingly, I will argue — the argument from marginal cases, points out that the criteria that are com- monly used to deprive nonhuman animals of moral consideration fail to draw a line between human beings and other sentient animals, since there are also humans who fail to satisfy them.1 This argument has been widely used in the literature on animal ethics for two purposes. -

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 Credits) Course Description

PHIL 221 – Ethical Theory (3 credits) Course Description: This course focuses on theories of morality rather than on contemporary moral issues (that is the topic of PHIL 120). That means that we will primarily be preoccupied with exploring what it means for an action—or a person—to be “good”. We will attempt to answer this question by looking at a mix of historical and contemporary texts primarily drawn from the Western European tradition, but also including some works from China and pre-colonial central America. We will begin by asking whether there are any universal and objectively valid moral rules, and chart several attempts to answer in both the affirmative and the negative: relativism, egoism, virtue ethics, consequentialism, deontology, the ethics of care, and contractarianism. We will consider the relationship between morality and the law, and whether morality is linked to human happiness. Finally, we will consider arguments for and against the idea that moral facts actually exist. Schedule of Readings Week 1 Introduction What are we trying to do? Charles L. Stevenson – The Nature of Ethical Disagreement Tom Regan – How Not to Answer Moral Questions Week 2 Relativism What counts as good depends on the moral standards of the group doing the evaluating. Mary Midgley – Trying Out One’s New Sword Martha Nussbaum – Judging Other Cultures: The Case of Genital Mutilation Plato – The Myth of Gyges (Republic II) Week 3 Egoism What’s good is just what’s good for me. Mencius – Mengzi (excerpts) James Rachels – Egoism and Moral Skepticism Week 4 Virtue Ethics Morality depends on having a virtuous character. -

Review Of" Science and Poetry" by M. Midgley

Swarthmore College Works Philosophy Faculty Works Philosophy 10-1-2003 Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley Hans Oberdiek Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy Part of the Philosophy Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Hans Oberdiek. (2003). "Review Of "Science And Poetry" By M. Midgley". Ethics. Volume 114, Issue 1. 187-189. DOI: 10.1086/376710 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-philosophy/121 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mary Midgley, Science and Poetry Science and Poetry by Mary. Midgley, Review by: Reviewed by Hans Oberdiek Ethics, Vol. 114, No. 1 (October 2003), pp. 187-189 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/376710 . Accessed: 09/06/2015 16:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethics. -

Death-Free Dairy? the Ethics of Clean Milk

J Agric Environ Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-018-9723-x ARTICLES Death-Free Dairy? The Ethics of Clean Milk Josh Milburn1 Accepted: 10 January 2018 Ó The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract The possibility of ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy produced without the need for cows—has been championed by several charities, companies, and individuals. One can ask how those critical of the contemporary dairy industry, including especially vegans and others sympathetic to animal rights, should respond to this prospect. In this paper, I explore three kinds of challenges that such people may have to clean milk: first, that producing clean milk fails to respect animals; second, that humans should not consume dairy products; and third, that the creation of clean milk would affirm human superiority over cows. None of these challenges, I argue, gives us reason to reject clean milk. I thus conclude that the prospect is one that animal activists should both welcome and embrace. Keywords Milk Á Food technology Á Biotechnology Á Animal rights Á Animal ethics Á Veganism Introduction A number of businesses, charities, and individuals are working to develop ‘‘clean milk’’—dairy products created by biotechnological means, without the need for cows. In this paper, I complement scientific work on this possibility by offering the first normative examination of clean dairy. After explaining why this question warrants consideration, I consider three kinds of objections that vegans and animal activists may have to clean milk. First, I explore questions about the use of animals in the production of clean milk, arguing that its production does not involve the violation of & Josh Milburn [email protected] http://josh-milburn.com 1 Department of Politics, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK 123 J. -

Animal Ethics and the Political

This is a repository copy of Animal Ethics and the Political. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/103896/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Cochrane, A. orcid.org/0000-0002-3112-7210, Garner, R. and O'Sullivan, S. (2016) Animal Ethics and the Political. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy. ISSN 1369-8230 https://doi.org/10.1080/13698230.2016.1194583 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy on 09/06/2016, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/13698230.2016.1194583. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Alasdair Cochrane, Robert Garner and Siobhan O’Sullivan Animal Ethics and the Political (forthcoming in Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy) Some of the most important recent contributions to normative debates concerning our obligations to nonhuman animals appear to be somehow ‘political’.i Certainly, many of those contributions have come from those working in the field of political, rather than moral, philosophy. -

Legal Research Paper Series

Legal Research Paper Series NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY By Rita K. Lomio and J. Paul Lomio Research Paper No. 6 October 2005 Robert Crown Law Library Crown Quadrangle Stanford, California 94305-8612 NON HUMAN ANIMALS AND THE LAW: A BIBLIOGRPAHY OF ANIMAL LAW RESOURCES AT THE STANFORD LAW LIBRARY I. Books II. Reports III. Law Review Articles IV. Newspaper Articles (including legal newspapers) V. Sound Recordings and Films VI. Web Resources I. Books RESEARCH GUIDES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES Hoffman, Piper, and the Harvard Student Animal Legal Defense Fund The Guide to Animal Law Resources Hollis, New Hampshire: Puritan Press, 1999 Reference KF 3841 G85 “As law students, we have found that although more resources are available and more people are involved that the case just a few years ago, locating the resource or the person we need in a particular situation remains difficult. The Guide to Animal Law Resources represents our attempt to collect in one place some of the resources a legal professional, law professor or law student might want and have a hard time finding.” Guide includes citations to organizations and internships, animal law court cases, a bibliography, law schools where animal law courses are taught, Internet resources, conferences and lawyers devoted to the cause. The International Institute for Animal Law A Bibliography of Animal Law Resources Chicago, Illinois: The International Institute for Animal Law, 2001 KF 3841 A1 B53 Kistler, John M. Animal Rights: A Subject Guide, Bibliography, and Internet Companion Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000 HV 4708 K57 Bibliography divided into six subject areas: Animal Rights: General Works, Animal Natures, Fatal Uses of Animals, Nonfatal Uses of Animals, Animal Populations, and Animal Speculations.