3.0 HISTORIC PERSPECTIVE on FRINK PARK “Although I Have Been Familiar with Frink Park in a General Way, in Consequence of My S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks and Recreation

PARKS AND RECREATION Parks and Recreation Overview of Facilities and Programs The Department of Parks and Recreation manages 400 parks and open areas in its approximately 6,200 acres of property throughout the City, works with the public to be good stewards of the park system, and provides safe and welcoming opportunities for the public to play, learn, contemplate, and build community. The park system comprises about 10% of the City’s land area; it includes 485 buildings, 224 parks, 185 athletic fields, 122 children's play areas, 24 community centers, 151 outdoor tennis courts, 22 miles of boulevards, an indoor tennis center, two outdoor and eight indoor swimming pools, four golf courses, studios, boat ramps, moorage, fishing piers, trails, camps, viewpoints and open spaces, a rock climbing site, a conservatory, a classical Japanese garden, and a waterfront aquarium. The development of this system is guided by the Seattle Parks & Recreation Plan 2000, the 38 neighborhood plans, the Joint Athletic Facilities Development Program with the Seattle School District, the 1999 Seattle Center and Community Centers Levy, the 2000 Parks Levy, and DPR’s annual update to the Major Maintenance Plan. 2000 Parks Levy In November 2000, Seattle voters approved a $198.2 million levy lid lift for Parks and Recreation. The levy closely follows the plan forged by the Pro Parks 2000 Citizens Planning Committee. The levy is designed to fund more than 100 projects to improve maintenance and enhance programming of existing parks, including the Woodland Park Zoo; acquire, develop and maintain new neighborhood parks, green spaces, playfields, trails and boulevards; and add out-of-school and senior activities. -

A Driving Force

N011V&Then byPaulDorpat T H E N : A caravan of motorcars featuring the Seattle Press Club in at least one pennant proceeds north past Mount Baker on a new Lake Washington Boulevard. The lakeshore was considerably changed in 1916 when the lake was lowered for the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. NOW: Cars still make the scenic loop along the lake. A Driving Force 0 5 the parkway the Olmsted Brothers envisioned ~ ~~~~~!~~;~rs~ ~~e ~a~~~~~e~~~~~e~~ when they planned the city's parks and boule gers or even the occasion that prompted such vards in the early 20th century. Their highest a long caravan to snake along Lake Wash ambitions were to purchase the entire west ington Boulevard through the Mount Baker side of the lake up to the ridge between Col cutves and into Colman Park. man and Leschi parks and carry the boulevard I do, however, speculate. The year may be to a scenic "crestline." Instead, the parkway 1909, when thispartofthe boulevard was new. was developed into a string of parks that often If so, then the motorcade is probably headed meanders with the boulevard. for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, which When the lake was lowered 9 feet in 1916, opened chat spring on the University of Wash the concrete and riprap seawalls were exposed. ington campus. Pieces of the boulevard were Here at Mount Baker the seawall was kept, and rushed to completion so processions like this a new, landscaped slope drops from it to the one could cover the distance from Wetmore shoreline. -

Frommer's Seattle 2004

01 541277 FM.qxd 11/17/03 9:37 AM Page i Seattle 2004 by Karl Samson Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers 01 541277 FM.qxd 11/17/03 9:37 AM Page ii About the Author Karl Samson makes his home in the Northwest. He also covers the rest of Wash- ington for Frommer’s. In addition, Karl is the author of Frommer’s Arizona. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report

City of Madison, Wisconsin Underrepresented Communities Historic Resource Survey Report By Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB, Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA and Robert Short, Associate AIA Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 and Jason Tish Archetype Historic Property Consultants 2714 Lafollette Avenue Madison, Wisconsin 53704 Project Sponsoring Agency City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development 215 Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard Madison, Wisconsin 53703 2017-2020 Acknowledgments The activity that is the subject of this survey report has been financed with local funds from the City of Madison Department of Planning and Community and Economic Development. The contents and opinions contained in this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the city, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the City of Madison. The authors would like to thank the following persons or organizations for their assistance in completing this project: City of Madison Richard B. Arnesen Satya Rhodes-Conway, Mayor Patrick W. Heck, Alder Heather Stouder, Planning Division Director Joy W. Huntington Bill Fruhling, AICP, Principal Planner Jason N. Ilstrup Heather Bailey, Preservation Planner Eli B. Judge Amy L. Scanlon, Former Preservation Planner Arvina Martin, Alder Oscar Mireles Marsha A. Rummel, Alder (former member) City of Madison Muriel Simms Landmarks Commission Christina Slattery Anna Andrzejewski, Chair May Choua Thao Richard B. Arnesen Sheri Carter, Alder (former member) Elizabeth Banks Sergio Gonzalez (former member) Katie Kaliszewski Ledell Zellers, Alder (former member) Arvina Martin, Alder David W.J. McLean Maurice D. Taylor Others Lon Hill (former member) Tanika Apaloo Stuart Levitan (former member) Andrea Arenas Marsha A. -

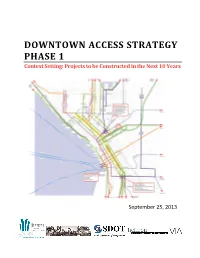

Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to Be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents

DOWNTOWN ACCESS STRATEGY PHASE 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years Table of Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 II. Review of Existing Plans, Projects, and Programs ......................................... 2 III. Potential Construction Concerns and Opportunities .................................. 3 A. Existing Construction Planning Tools 3 B. SDOT’s Construction Hub Coordination Program 4 C. Construction Mitigation Strategies Used by Other Cities 7 D. Potential Construction Conflicts and Opportunities 10 IV. Future Transportation Network Opportunities ......................................... 12 A. North Downtown 12 B. Denny Triangle / Westlake Hub 14 C. Pioneer Square / Chinatown-ID 15 D. Downtown Core and Waterfront 16 V. Future Phases of Downtown Access Strategy ............................................. 18 A. Framework for Phase 2 (2014 through 2016) 18 B. Framework for Phase 3 (Beyond 2016) 19 - i - September 25, 2013 Downtown Access Strategy Phase 1 Context Setting: Projects to be Constructed in the Next 10 Years I. INTRODUCTION Many important and long planned transportation and development projects are scheduled for con- struction in Downtown Seattle in the coming years. While these investments are essential to support economic development and job growth and to enhance Downtown’s stature as the region’s premier location to live, work, shop and play, in the short-term they present complicated challenges for con- venient and reliable access to and through Downtown. The Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) and its partners, Historic South Downtown (HSD) and the Seat- tle Department of Transportation (SDOT), seek to ensure that Downtown Seattle survives and prospers during the extraordinarily high level of construction activity that will occur in the coming years. -

Copy of Censusdata

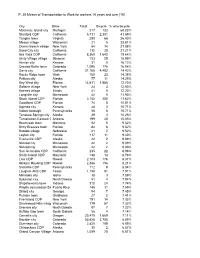

P. 30 Means of Transportation to Work for workers 16 years and over [16] City State Total: Bicycle % who bicycle Mackinac Island city Michigan 217 132 60.83% Stanford CDP California 5,711 2,381 41.69% Tangier town Virginia 250 66 26.40% Mason village Wisconsin 21 5 23.81% Ocean Beach village New York 64 14 21.88% Sand City city California 132 28 21.21% Isla Vista CDP California 8,360 1,642 19.64% Unity Village village Missouri 153 29 18.95% Hunter city Kansas 31 5 16.13% Crested Butte town Colorado 1,096 176 16.06% Davis city California 31,165 4,493 14.42% Rocky Ridge town Utah 160 23 14.38% Pelican city Alaska 77 11 14.29% Key West city Florida 14,611 1,856 12.70% Saltaire village New York 24 3 12.50% Keenes village Illinois 41 5 12.20% Longville city Minnesota 42 5 11.90% Stock Island CDP Florida 2,152 250 11.62% Goodland CDP Florida 74 8 10.81% Agenda city Kansas 28 3 10.71% Volant borough Pennsylvania 56 6 10.71% Tenakee Springs city Alaska 39 4 10.26% Tumacacori-Carmen C Arizona 199 20 10.05% Bearcreek town Montana 52 5 9.62% Briny Breezes town Florida 84 8 9.52% Barada village Nebraska 21 2 9.52% Layton city Florida 117 11 9.40% Evansville CDP Alaska 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% Nimrod city Minnesota 22 2 9.09% San Geronimo CDP California 245 22 8.98% Smith Island CDP Maryland 148 13 8.78% Laie CDP Hawaii 2,103 176 8.37% Hickam Housing CDP Hawaii 2,386 196 8.21% Slickville CDP Pennsylvania 112 9 8.04% Laughlin AFB CDP Texas 1,150 91 7.91% Minidoka city Idaho 38 3 7.89% Sykeston city North Dakota 51 4 7.84% Shipshewana town Indiana 310 24 7.74% Playita comunidad (Sa Puerto Rico 145 11 7.59% Dillard city Georgia 94 7 7.45% Putnam town Oklahoma 27 2 7.41% Fire Island CDP New York 191 14 7.33% Shorewood Hills village Wisconsin 779 57 7.32% Grenora city North Dakota 97 7 7.22% Buffalo Gap town South Dakota 56 4 7.14% Corvallis city Oregon 23,475 1,669 7.11% Boulder city Colorado 53,828 3,708 6.89% Gunnison city Colorado 2,825 189 6.69% Chistochina CDP Alaska 30 2 6.67% Grand Canyon Village Arizona 1,059 70 6.61% P. -

The Artists' View of Seattle

WHERE DOES SEATTLE’S CREATIVE COMMUNITY GO FOR INSPIRATION? Allow us to introduce some of our city’s resident artists, who share with you, in their own words, some of their favorite places and why they choose to make Seattle their home. Known as one of the nation’s cultural centers, Seattle has more arts-related businesses and organizations per capita than any other metropolitan area in the United States, according to a recent study by Americans for the Arts. Our city pulses with the creative energies of thousands of artists who call this their home. In this guide, twenty-four painters, sculptors, writers, poets, dancers, photographers, glass artists, musicians, filmmakers, actors and more tell you about their favorite places and experiences. James Turrell’s Light Reign, Henry Art Gallery ©Lara Swimmer 2 3 BYRON AU YONG Composer WOULD YOU SHARE SOME SPECIAL CHILDHOOD MEMORIES ABOUT WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO SEATTLE? GROWING UP IN SEATTLE? I moved into my particular building because it’s across the street from Uptown I performed in musical theater as a kid at a venue in the Seattle Center. I was Espresso. One of the real draws of Seattle for me was the quality of the coffee, I nine years old, and I got paid! I did all kinds of shows, and I also performed with must say. the Civic Light Opera. I was also in the Northwest Boy Choir and we sang this Northwest Medley, and there was a song to Ivar’s restaurant in it. When I was HOW DOES BEING A NON-DRIVER IMPACT YOUR VIEW OF THE CITY? growing up, Ivar’s had spokespeople who were dressed up in clam costumes with My favorite part about walking is that you come across things that you would pass black leggings. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. ___X___ New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Seattle’s Olmsted Parks and Boulevards (1903–68) B. Associated Historic Contexts None C. Form Prepared by: name/title: Chrisanne Beckner, MS, and Natalie K. Perrin, MS organization: Historical Research Associates, Inc. (HRA) street & number: 1904 Third Ave., Suite 240 city/state/zip: Seattle, WA 98101 e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] telephone: (503) 247-1319 date: December 15, 2016 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. _______________________________ ______________________ _________________________ Signature of certifying official Title Date _____________________________________ State or Federal Agency or Tribal government I hereby certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Leschi/Judkins Park

LESCHI/JUDKINS PARK DEVELOPMENT SITE SEATTLE SBD CAPITOL HILL PIONEER SQUARE JUDKINS PARK CENTRAL DISTRICT LESCHI KIRKLAND REDMOND UNIVERSITY DISTRICT FREMONT WALLINGFORD MADISON VALLEY QUEEN ANNE CAPITOL SLU MADISON HILL PARK MADRONA SEATTLE CBD CENTRAL BELLEVUE DISTRICT LESCHI LESCHI/JUDKINS PARK DEVELOPMENT SITE FUTURE JUDKINS PARK LIGHT RAIL STATION (2023) MT. BAKER BEACON HILL MERCER ISLAND INDUSTRIAL DISTRICT OFFERING Amazing Leschi/Judkins Park Opportunity! How often do you find a perfect project that literally bridges Seattle & Eastside Employment Hubs & is smartly sited in a charming neighborhood w/ coveted amenities & parks? It’s rare. This sizeable, partially permitted 20 townhouse project w/ an unbeatable location is a mere .5 mi to upcoming Eastlink Light Rail station, which will seamlessly connect Seattle & Eastside employment options. Your end-user pool just doubled. Look to the post-COVID urban lifestyle demand this project offers. 3 tax parcels- 25,451 sq ft in total, zoned LR2. If Light Rail & local mixed-use redevelopment hubs don’t excite you, perhaps the short 15 min drive to all Major employment centers of DT Seattle, SLU & Bellevue will. Seller is pursuing permits for a 20-unit townhouse project currently in the entitlement process, past Design Review with the City of Seattle. NAME Leschi/Judkins Park Development Site 800 28th Ave S, Seattle, WA 98144 ADDRESS 811 29th Ave S, Seattle, WA 98144 2801 S Dearborn St, Seattle, WA 98144 PARCEL NUMBERS 636290-0265, 056700-0612, 056700-0614 LOT SQUARE FEET 9,779 + 7,946 + 7,726 = 25,451 Square Feet ZONING LR2 (M) PRICE $6,300,000 PRICE PER LOT FOOT $246 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 20 Townhouses TERMS Cash Out This information has been secured from sources we believe to be reliable, but we make no representations or warranties, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy of the information. -

ALASKAN WAY VIADUCT REPLACEMENT PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement

ALASKAN WAY VIADUCT REPLACEMENT PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX L Economics Discipline Report Submitted by: PARSONS BRINCKERHOFF Prepared by: PARSONS BRINCKERHOFF J U L Y 2 0 1 1 Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project Final EIS Economics Discipline Report The Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project is a joint effort between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), and the City of Seattle. To conduct this project, WSDOT contracted with: Parsons Brinckerhoff 999 Third Avenue, Suite 3200 Seattle, WA 98104 In association with: Coughlin Porter Lundeen, Inc. EnviroIssues, Inc. GHD, Inc. HDR Engineering, Inc. Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. Magnusson Klemencic Associates, Inc. Mimi Sheridan, AICP Parametrix, Inc. Power Engineers, Inc. Shannon & Wilson, Inc. William P. Ott Construction Consultants SR 99: Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project July 2011 Economics Discipline Report Final EIS This Page Intentionally Left Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction and Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Build Alternatives Overview ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Overview of Bored Tunnel Alternative (Preferred) .......................................................................... -

Minutes – Annual Run/Walk/Ride Meeting Wednesday, November 13, 2019 10:00Am – 12:00Pm Seattle Municipal Tower, Room 4050/4060

Special Events Committee Meeting Minutes – Annual Run/Walk/Ride Meeting Wednesday, November 13, 2019 10:00am – 12:00pm Seattle Municipal Tower, Room 4050/4060 Special Events Committee Attendees: Angela Rae Department of Neighborhoods Glenn Bartolome KC Metro A/Lt. Morlon Malveaux Medic One Carl Bergquist Parks Rosemary Byrne Public Health Dan Powers SDCI Noise Abatement Mike Shea SDOT Gretchen Lenihan Seattle Center, Acting Chair Lt. Phil Hay SPD Traffic James Olson SPD Pat Kaufman Seattle Public Utilities Julie Borden Special Events Jonelle Mogi Special Events Capt. Tom Dixon WSLCB Lt. Rob Rieder WSLCB Run/Walk/Ride Organizer Attendees: Valerie Robinson American Cancer Society Carla Gochicoa American Heart Association Tom Anderson AndEvents, Inc Ashley Moise Arthritis Foundation Sue Verduin Ballard Foundation, Running of the Beavers P. Alex Comeau Cascade Bicycle Club David Douglas Cascade Bicycle Club Jared Lorganger Fizz Events Nancy Polichene Gray Day Events Aissa Perez Komen Puget Sound Lisa Miller Montlake Turkey Trot Lauren Kelly National MS Society Natalie Plutt National MS Society Ashley Lee Orca Running Danette Felt Resolution to End Homelessness Ilana Balint Run for Good Sue Verduin Running of the Beavers 700 5th Avenue, Suite 5752, PO Box 94708, Seattle, WA 98124 Tel: 206-684-8017 Fax: 206-684-7025 Seattle Special Events Committee Meeting – 11/13/2019 Grant Harrington Snohomish Running Company Jaclyn Rodriguez Swedish Amanda Schulte Swedish Chad Evans The Color Run Additional Attendees: Katy Willis – Visit Seattle Introduction The purpose of the annual run/walk/ride meeting is to (1) review dates, locations, and conflicts between the historic and proposed new events each year, and (2) identify construction, other events or work that may impact run/walk/ride events. -

This City of Ours

THIS CITY OF OURS By J. WILLIS SAYRE For the illustrations used in this book the author expresses grateful acknowledgment to Mrs. Vivian M. Carkeek, Charles A. Thorndike and R. M. Kinnear. Copyright, 1936 by J. W. SAYRE rot &?+ *$$&&*? *• I^JJMJWW' 1 - *- \£*- ; * M: . * *>. f* j*^* */ ^ *** - • CHIEF SEATTLE Leader of his people both in peace and war, always a friend to the whites; as an orator, the Daniel Webster of his race. Note this excerpt, seldom surpassed in beauty of thought and diction, from his address to Governor Stevens: Why should I mourn at the untimely fate of my people? Tribe follows tribe, and nation follows nation, like the waves of the sea. It is the order of nature and regret is useless. Your time of decay may be distant — but it will surely come, for even the White Man whose God walked and talked with him as friend with friend cannot be exempt from the common destiny. We may be brothers after all. Let the White Man be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead — I say? There is no death. Only a change of worlds. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1. BELIEVE IT OR NOT! 1 2. THE ROMANCE OF THE WATERFRONT . 5 3. HOW OUR RAILROADS GREW 11 4. FROM HORSE CARS TO MOTOR BUSES . 16 5. HOW SEATTLE USED TO SEE—AND KEEP WARM 21 6. INDOOR ENTERTAINMENTS 26 7. PLAYING FOOTBALL IN PIONEER PLACE . 29 8. STRANGE "IFS" IN SEATTLE'S HISTORY . 34 9. HISTORICAL POINTS IN FIRST AVENUE . 41 10.