The Dynamic Nature of Kata an Interview with Steven R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WPB Judo Academy Parents and Judoka Handbook

WPB Judo Academy 2008 Parents and Judoka Handbook Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques O-soto-otoshi O-soto-gari Ippon-seio-nage De-ashi-barai Tai-otoshi Major Outer Drop Major Outer One Arm Shoulder Advancing Foot Body Drop Throw Sweep O-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gake Ko-soto-gake Ko-soto-gari Major Inner Reaping Minor Inner Reaping Minor Inner Hook Minor Outer Hook Minor Outer Reap Uki-goshi O-goshi Tsuri-goshi Floating Hip Throw Major Hip Throw Lifting Hip Throw Osae-Waza - Holding Techniques Kesa-gatame Yoko-shiho-gatame Kuzure-kesa-gatme Scarf Hold Side 4 Quarters Broken Scarf Hold Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques Morote-seio-nage O-goshi Uki-goshi Tsuri-goshi Koshi-guruma Two Arm Shoulder Major Hip Throw Floating Hip Throw Lifting Hip Throw Hip Whirl Throw Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi Tsuri-komi-goshi Sasae-tsuri-komi-ashi Tsubame-gaeshi Okuri-ashi-barai Sleeve Lifting Pulling Lifting Pulling Hip Lifting Pulling Ankle Swallow’s Counter Following Foot Hip Throw Throw Block Sweep Shime-Waza - Strangulations Nami-juji-jime Normal Cross Choke Ko-soto-gake Ko-soto-gari Ko-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gake Minor Outer Hook Minor Outer Reap Minor Inner Reap Minor Inner Hook Osae-Waza - Holding Techniques Kansetsu-Waza - Joint Locks Gyaku-juji-jime Reverse Cross Choke Kami-shiho-gatame Kuzure-kami-shiho-gatame Upper 4 Quarters Hold Broken Upper 4 Quarters Hold Ude-hishigi-juji-gatme Cross Arm Lock Tate-shiho-gatame Kata-juji-jime Mounted Hold Half Cross Choke Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques Harai-goshi Kata-guruma Uki-otoshi Tsuri-komi-goshi Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi -

Kodomo-No-Kata – Forms for Children Llŷr Jones July 2020

Issue No. 45 Kodomo-no-kata – Forms for Children Llŷr Jones July 2020 Introduction Contents Kodomo means “child/children” in Japanese, so the literal translation of Kodomo- • Kodomo-no-kata – Forms for Chil- no-kata 子どもの形 is “Forms for children”. The exercise has been created as the dren by Llyr̂ Jones result of a concentrated and cooperative effort by the Kodokan Judo Institute, the • Yukichi Fukuzawa (1835–1901) by International Judo Federation (IJF) and the French Judo Federation to help children Brian Watson; learn the basics of judo in a safe and progressive manner. Kodomo-no-kata sys- • The Essence of Judo: Turning Nega- temises what children should learn first when they begin practicing judo and one of tives into Positives by Brian Watson; the specific motivations behind its creation was to provide a tool for judo teachers working in countries where there are very few experienced instructors [1]. • The Richard Bowen Collection. In This Edition This edition of “The Bulletin” features an article on the new children’s kata – Kodomo-no-kata by Llyr̂ Jones; one on the Japanese author, educator, and pub- lisher, Yukichi Fukuzawa by Brian Wat- son; and one reflecting on the essence of judo and turning negatives into positives, again by Brian Watson. Thank you both. Publisher’s Comments As this issue of “The Bulletin” (produced by guest editor Llyr̂ Jones) is published, the Covid-19 public health crisis contin- ues to upend all aspects of our lives. It has brought a major hiatus to the physi- cal practice of judo in almost every coun- try in the world and even when re- strictions start to be eased, a return to how practice was at the start of 2020 is undoubtedly still some way off. -

BJA Kata Award Scheme

BRITISH JUDO ASSOCIATION KATA AWARD SCHEME 1st June 2020 KATA AWARD SCHEME INTRODUCTION This document comes into effect on 1st June 2020 and supersedes all previously published material. KATA Kata are prearranged and abstract attack/defence choreographic forms, which represent the grammar of judo. The Kodokan Judo Institute define kata as: • Formal movement pattern exercises containing idealised model movements illustrating specific combative principles . Source: Kodokan New Japanese-English Dictionary of Judo THE KATA RECOGNISED KATA The British Judo Association (BJA) recognises and provides certification for the following eight kata: Kata English Translation Heritage Nage-no-Kata Forms of Throwing Kodokan Katame-no-Kata Forms of Control Kodokan Ju-no-Kata Forms of Gentleness and Flexibility Kodokan Kime-no-Kata Forms of Decisive Techniques Kodokan Kodokan Goshin-jutsu Kodokan Skills of Self-defence Kodokan Itsutsu-no-Kata Kodokan Koshiki-no-Kata Forms of Classics Kodokan (BJA) Gonosen-no-Kata (BJA) Forms of Counterattack Non-Kodokan NAGE-NO-KATA FORMS OF THROWING Nage-no-Kata was established to help understanding of the theoretical basis of judo and learn the processes involved in Kuzushi, Tsukuri, Kake that is how to assume the correct position for applying a throwing technique once the opponents balance has been broken, and how to apply and complete a technique. Nage-no-Kata consists of 15 representative throwing techniques as follows, with each technique being executed from both sides. Te-waza (Hand Techniques) • Uki-otoshi (Floating -

COMPETITION DE KATA Critères D'évaluation

COMPETITION DE KATA Critères d’évaluation FÉDÉRATION INTERNATIONALE DE JUDO COMMISSION KATA JANVIER 2019 ÉLÉMENTS GÉNÉRAUX L’évaluation de chacune des techniques des kata doit prendre en considération le principe et l’opportunité d’exécution: l’évaluation (comprenant les cérémonies d’ouverture et de fermeture) doit être globale. Les éléments observés sont la manière correcte de faire les techniques, au cas où vous remarqueriez une erreur, pénalisez en fonction du type d’erreurs dans ce document. Définition des erreurs: • Technique oubliée Une technique oubliée sera notée zéro, de plus le score final du couple de kata sera réduit de moitié. Si plus d’une technique est oubliée, la note pour cette technique sera aussi de zéro, mais le résultat final du couple ne sera plus réduit de moitié une autre fois. Tori ne fait pas la technique appropriée après l'attaque de Uke = Technique oubliée. • Grande erreur Quand l’exécution d’un principe est incorrecte (5 points sont déduits, le maximum de croix est 1). • Erreur moyenne Quand un ou plusieurs éléments d’un principe ne sont pas appliqués correctement (3 points sont déduits, le maximum de croix est 1). • Petite erreur Imperfection dans l’application d’une technique (1 point est déduit, le nombre maximum de croix est 2). Pour chacune des techniques sans grande erreur, le résultat minimum doit être 4.5 . Pour chaque technique, une évaluation de 0,5 peut être ajoutée (+) ou soustraite (-). Dans le Nage no kata, les techniques à droite et à gauche seront évaluées globalement (1 seul résultat sera inscrit). Le score pour la fluidité, les déplacements et le rythme sont inclus dans chaque technique . -

Nokido Ju-Jitsu & Judo Student Handbook

Nokido Ju-Jitsu & Judo Student Handbook North Port, Florida Shihan Earl DelValle HISTORY OF JU-JITSU AND NOKIDO JU-JITSU Ju-Jitsu (Japanese: 柔術), is a Japanese Martial Art and a method of self defense. The word Ju- Jitsu is often spelled as Jujutsu, Jujitsu, Jiu-jutsu or Jiu-jitsu. "Jū" can be translated to mean "gentle, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding." "Jitsu" can be translated to mean "art" or "technique" and represents manipulating the opponent's force against himself rather than directly opposing it. Ju-Jitsu was developed among the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and unarmed opponent in which one uses no weapon. There are many styles (ryu) and variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches, but you will find that the different styles have similar, if not the same techniques incorporated into their particular style. Ju-Jitsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree (i.e. throwing, trapping, restraining, joint locks, and hold downs, disengagements, escaping, blocking, striking, and kicking). Japanese Ju-Jitsu grew during the Feudal era of Japan and was expanded by the Samurai Warriors. The first written record of Ju-Jitsu was in 1532 by Hisamori Takeuchi. Takenouchi Ryu Ju-Jitsu is the oldest style of Ju-jitsu and is still practiced in Japan. There are hundreds of different Ju-Jitsu styles that have been documented and are practiced today, one of which is our modern style of Ju-Jitsu, Nokido Ju-Jitsu. Ju-Jitsu is said to be the father of all Japanese Martial Arts. -

WD PG Kyu Grading Syllabus

Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus A Trail Form White Belt To Brown Belt Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus 5th Kyu YELLOW Belt KIHON (Basics) REI (Bow) Ritsu-rei: Standing bow Za-rei: Sitting bow SHISEI (Postions) Shizen-hon-tai: Basic natural guard (Migi/Hidari-shizen-tai: Right/Left) Jigo-hon-tai: Basic defensive guard (Migi/Hidari-jigo-tai: Right/Left) SHINTAI (walks, movements) Tsuri-ashi: Feet shuffling (in common with Ayumi-ashi, Tsugi-ashi and Tai-sabaki) Ayumi-ashi: Normal walk, “foot passes foot” (Mae/Ushiro: Forwards/Backwards) Tsugi-ashi: Walk “foot chases foot” (Mae/Ushiro, Migi/Hidari) Tai-sabaki: Pivot (90/180°, Mae-Migi/Hidari, Ushiro-Migi/Hidari); KUMI-KATA: Grips (Hon-Kumi-Kata, Basic grip, Migi/Hidari-K.-K., Right/Left) WAZA: Technique KUZUSHI, TSUKURI, KAKE: Unbalancing, Positioning, Throw (Phases of the techniques) HAPPO-NO-KUZUSHI: The eight directions of unbalancing UKEMI (Break-falls) Ushiro-ukemi: Backwards break-fall Yoko-ukemi: Side break-fall (Migi/Hidari-yoko-ukemi) Mae-ukemi: Forward break-fall Mae-mawari-ukemi: Rolling break-fall Zempo-kaiten-ukemi: Leaping rolling break-fall KEIKO (Training exercises) Uchi-komi: Repetitions of entrances (lifting) Butsukari: Repetitions of impacts (no lifting) Kakke-ai: Repetitions of throws Yakusoku-geiko: One technique each without any reaction from Uke Kakari-geiko: One attacking, the other defending using the gentle way Randori: Free training exercise Shiai: Competition fight 2 Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus NAGE-WAZA -

Judo Federation of Australia

JFA National Grading Policy Judo Federation of Australia National Grading Policy Version 1 “If there is effort, there is always accomplishment” – Jigoro Kano Page | 1 JFA National Grading Policy JFA National Grading Policy The teaching of Kano Jigoro Shihan Judo is the way of using one’s mental and physical strength in the most efficient manner. Through training and practicing techniques for offense and defense, one disciplines and cultivates body and spirit, and thereby masters the essence of this way. Thus, the ultimate goal of Judo is to strive for personal perfection by means of this and to benefit the world. JFA National Grading Policy TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1- NATIONAL GRADING POLICY OVERVIEW……………………………………………..1 1.1 INTERNATIONAL JUDO FEDERATION GRADING RATIONALE ............................................... 1 1.2 JUDO FEDERATION OF AUSTRALIA INTRODUCTION ............................................................. 1 1.3 PURPOSE OF THIS POLICY ........................................................................................................ 1 1.4 MISSION STATEMENT ................................................................................................................. 2 1.5 JFA VALUES ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.6 OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.7 GRADING AUTHORITIES ............................................................................................................ -

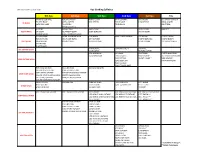

Kyu Grading Syllabus Summary

Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus 5th Kyu 4th Kyu 3rd Kyu 2nd Kyu 1st Kyu Extra MOROTE SEOI NAGE KUCHIKI DAOSHI MOROTE GARI KATA GURUMA UKI OTOSHI UCHI MATA SUKASHI ERI SEOI NAGE KIBISU GAESHI SEOI OTOSHI SUKUI NAGE SUMI OTOSHI YAMA ARASHI TE WAZA KATA SEOI NAGE TAI OTOSHI TE GURUMA OBI OTOSHI IPPON SEOI NAGE O GOSHI HARAI GOSHI HANE GOSHI TSURI GOSHI DAKI AGE KOSHI WAZA UKI GOSHI TSURIKOMI GOSHI KOSHI GURUMA UTSURI GOSHI USHIRO GOSHI SODE TSURIKOMI GOSHI DE ASHI BARAI SASAE TSURIKOMI ASHI UCHI MATA ARAI TSURIKOMI ASHI O GURUMA O UCHI GAESHI HIZA GURUMA OKURI ASHI BARAI ASHI GURUMA O SOTO GURUMA O SOTO GAESHI ASHI WAZA KO UCHI GARI KO SOTO GARI O SOTO OTOSHI KO SOTO GAKE UCHI MATA GAESHI O UCHI GARI O SOTO GARI TOMOE NAGE HIKIKOMI GAESHI URA NAGE MA SUTEMI WAZA SUMI GAESHI TAWARA GAESHI UCHI MAKIKOMI UKI WAZA YOKO GAKE O SOTO MAKIKOMI SOTO MAKIKOMI TANI OTOSHI KANI BASAMI * UCHI MATA MAKIKOMI YOKO OTOSHI KAWAZU GAKE * DAKI WAKARE YOKO SUTEMI WAZA YOKO GURUMA HARAI MAKIKOMI YOKO WAKARE YOKO TOMOE NAGE HON KESA GATAME KATA GATAME SANKAKU GATAME KUZURE KESA GATAME KAMI SHIHO GATAME YOKO SHIHO GATAME KUZURE KAMI SHIHO GATAME OSAE KOMI WAZA KUZURE YOKO SHIHO GATAME USHIRO KESA GATAME TATE SHIHO GATAME MAKURA KESA GATAME KUZURE TATE SHIHO GATAME KATA JUJI JIME HADAKA JIME OKURI ERI JUME TSUKKOMI JIME RYO TE JIME NAMI JUJI JIME KATA HA JIME SODE GURUMA JIME KATA TE JIME SHIME WAZA GYAKU JUJI JIME SANKAKU JIME DO JIME * UDE HISHIGI JUJI GATAME UDE HISHIGI HARA GATAME UDE GARAMI UDE HISHIGI UDE GATAME UDE HISHIGI ASHI GATAME UDE -

Nage No Kata in the Current Competitive Judo

STUDIA UBB EDUCATIO ARTIS GYMN., LIX, 3, 2014, pp. 79 - 84 (RECOMMENDED CITATION) NAGE NO KATA IN THE CURRENT COMPETITIVE JUDO ION-PETRE BARBOŞ1 ABSTRACT. In the context of current judo coaches focus on exceptional tactical and physical training, but omit one of the main aspects in full and complete fighting techniques, namely Kata. Approaching strictly shiai techniques has many negative results. From small or large accidents to abandon sports activity, capping being the main cause. In recent years Japanese judo school has addressed Kata with great seriousness as a form of technical training. Taking the example of Kodokan Judo, federations around the world have begun to pay increasingly higher importance to Kata, which led to organizing national, continental and world championships. In Romania, Kata is practiced at a high level also. Our athletes, couple Surlă and Fleis, trained by the reputed professor Alexandru Chirila (5 Dan) won all European and World Championship titles in the last six years. Sports Club "University Dinamo Cluj" coach - assist. univ. dr. Barboş Ion Petre (2 Dan) has achieved remarkable results in the past three years (2010-2013) at the national level, with over 10 medals (gold, silver and bronze) won by athletes at Nage no Kata, Katame no Kata, Ju no Kata, Kodokan Goshin Jutsu. This article attemps to highlight the overwhelming importance of addressing Kata judo in training juniors, seniors and veterans judo athletes. Keywords: Judo shiai, kata, Nage no Kata, kyu, Shisei, shizentai, jigotai, Ma ai, Kodokan Judo Kata Kum, Kasumi, Mae-Mawar-sabaki REZUMAT. Kata în Judo competiţional actual. În contextul judo-ului actual antrenorii pun accent pe pregătirea tactică şi fizică de excepţie, dar omit unul dintre principalele aspecte ale realizării depline şi complete a unei tehnici de luptă, şi anume, Kata. -

Seishin Judo Promotion Requirements

SEISHINJUDO AT SANDIA JUDO CLUB LINDA YIANNAKIS, 5TH DAN (USA-TKJ); 5TH DAN (USA JUDO) Requirements for Promotion The serious study of judo requires regular attendance, much persistence, an understanding of principles both physical and philosophical, and practice, practice, practice. Seishin Judo is committed to the study of the larger judo: judo as a way of life and a path as well as a powerful martial way. Classes focus on the principles that drive techniques and their application in various contexts. Students may advance in rank by meeting time in grade criteria and by demonstrating technical competence and theoretical and background knowledge. Randori, kata (formal and informal) and competition are the three main areas of judo application. Expectations and requirements in all three areas are stated at each grade level. In addition, attending clinics and seminars and providing supervised teaching (when appropriate) are required. Each test below includes a representative sampling of principles and techniques from judo. The tests do not represent a complete syllabus of judo. They also include techniques that are outside of the standard Kodokan program. This document is intended as a reference and study guide for the student. GOKYU (5th Kyu) Yellow Belt (All Testing is from Japanese Terminology) 1. Sound character and maturity 2. Minimum age of 14 years 3. Minimum time practicing Judo: 3 months 4. Regular dojo attendance 5. Good dojo hygiene 6. Good Judo/Jujutsu etiquette 7. Demonstrate competence in basic breakfalls 8. Demonstrate kiai and understanding of Judo spirit 9. Proper wearing and folding of the Judogi 10. Demonstrate standing and kneeling bows (ritsurei and zarei) 11. -

Midwest Academy Fundamentals Kihon Glossary

Midwest Academy of Martial Arts (630) 836 – 3600 Naperville, Il www.TheMidwestAcademy.com Seizan Ryu Kempo Jujutsu Fundamentals / Kihon English Japanese Positioning Tsukuri Notes Stances Shisei 1. Neutral stance 1. Chuitsu dachi 1. 2. Foundation stance 2. Kiso dachi 2. 3. Natural ready stance 3. Shizen yoi dachi 3. 4. Forward stance 4. Zenkutsu dachi 4. 5. Forward hook stance 5. Manji dachi 5. 6. Back stance 6. Kokutsu dachi 6. 7. Cat stance 7. Neko ashi dachi 7. 8. Crane Stance 8. Tsuru dachi 8. 9. Cross Stance 9. Juji dachi 9. 10. Hourglass Stance 10. Sunadokei dachi 10. 11. Pyramid 11. Shiho shisei 11. 12. Triangle/Offset triangle 12. Sankaku shisei 12. 13. Hurdler 13. Shogai shisei 13. Postures / Guards Kamae 1. Salutation Posture 1. Gassho gamae 1. 2. Standing attention posture 2. Kiritsu chumoku gamae 2. 3. Standing bow 3. Kiritsu rei 3. 4. Seated attention posture 4. Suwari chumoku gamae 4. 5. Seated bow 5. Suwari rei 5. 6. Meditation posture 6. Seiza gamae 6. 7. Fundamental posture 7. Kihon gamae 7. 8. High ready guard 8. Jodan yoi gamae 8. 9. Middle ready guard 9. Chudan yoi gamae 9. 10. Low ready guard 10. Gedan yoi gamae 10. 11. Single knee guard 11. Ippon hizamazuki gamae 11. Dodges Sorashi 1. Side dodge 1. Yoko sorashi 1. 2. Circular dodge 2. Marui sorashi 2. 3. Half Turn 3. Han tenkan 3. 4. Leg wave 4. Nami ashi 4. 5. Backwards dodge 5. Sorimi 5. 6. Pull in dodge 6. Hikimi 6. Footwork Ashi waza 1. Gliding step 1. -

What You Will Be Tested on for Each Rank

What you will be tested on for each rank White 1S Osoto Otoshi Ogoshi Yellow Osoto Otoshi Ogoshi Ippon Seoi Nage Osoto Gari Kesa Gatame Kuzure Kesa Gatame Yellow 1S Ippon Seoi Nage Osoto Gari Kesa Gatame Kuzure Kesa Gatame Tai otoshi Koshi Guruma Makura Kesa Gatame Ushiro Kesa Gatame Yellow 2S Tai otoshi Koshi Guruma Makura Kesa Gatame Ushiro Kesa Gatame Morote Seoi Nage Uki Goshi Yoko Shiho Gatame Kuzure Yoko Shihi Gatame Orange Morote Seoi Nage Uki Goshi Yoko Shiho Gatame Kuzure Yoko Shihi Gatame Ouchi Gari Hiza Guruma Kami Shiho Gatame Kazure Kami Shiho Gatame Orange 1S Ouchi Gari Hiza Guruma Kami Shiho Gatame Kazure Kami Shiho Gatame Kouchi Gari Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Tate Shiho Gatame Kuzure Tate Shiho Gatame Orange 2S Kouchi Gari Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Tate Shiho Gatame Kuzure Tate Shiho Gatame Tsurikomi Goshi Sode Tsurikomi Goshi Kata Gatame Green Tsurikomi Goshi Sode Tsurikomi Goshi Kata Gatame Harai Goshi Okuri Ashi Barai Hadaka Jime Green 1S Harai Goshi Okuri Ashi Barai Hadaka Jime Uchi Mata Deashi Barai Okuri Eri Jime Kata Ha Jime Green 2S Uchi Mata Deashi Barai Okuri Eri Jime Kata Ha Jime Kosoto Gari Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Ryote Jime Blue Kosoto Gari Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Ryote Jime Hane Goshi Ushiro Goshi Gyaku Juji Jime Nami Juji Jime Kata Juji Jime Blue 1S Hane Goshi Ushiro Goshi Gyaku Juji Jime Nami Juji Jime Kata Juji Jime Ashi Guruma Tomoe Nage Ashi Gatame Jime Sode Guruma Jime Blue 2S Ashi Guruma Tomoe Nage Ashi Gatame Jime Sode Guruma Jime Kata Guruma Oguruma Ude Gatame Purple Kata Guruma Oguruma Ude Gatame Uki Waza Yoko Guruma Juji Gatame Ude Garami Purple 1S Uki Waza Yoko Guruma Juji Gatame Ude Garami Soto Makikomi Yoko Otoshi Hiza Gatame Purple 2S Soto Makikomi Yoko Otoshi Hiza Gatame Sukui Nage Utsuri Goshi Waki Gatame Hara Gatame.