Pine Nuts As an Aboriginal Food Source in California and Nevada: Some Contrasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinus Sabiniana) in Oregon Frank Callahan PO Box 5531, Central Point, OR 97502

Discovering Gray Pine (Pinus sabiniana) in Oregon Frank Callahan PO Box 5531, Central Point, OR 97502 “Th e tree is remarkable for its airy, widespread tropical appearance, which suggest a region of palms rather than cool pine woods. Th e sunbeams sift through even the leafi est trees with scarcely any interruption, and the weary, heated traveler fi nds little protection in their shade.” –John Muir (1894) ntil fairly recently, gray pine was believed to be restricted to UCalifornia, where John Muir encountered it. But the fi rst report of it in Oregon dates back to 1831, when David Douglas wrote to the Linnaean Society of his rediscovery of Pinus sabiniana in California. In his letter from San Juan Bautista, Douglas claimed to have collected this pine in 1826 in Oregon while looking for sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana) between the Columbia and Umpqua rivers (Griffin 1962). Unfortunately, Douglas lost most of his fi eld notes and specimens when his canoe overturned in the Santiam River (Harvey 1947). Lacking notes and specimens, he was reluctant to report his original discovery of the new pine in Oregon until he found it again in California (Griffin 1962). Despite the delay in reporting it, Douglas clearly indicated that he had seen this pine before he found it in California, and the Umpqua region has suitable habitat for gray pine. John Strong Newberry1 (1857), naturalist on the 1855 Pacifi c Railroad Survey, described an Oregon distribution for Pinus sabiniana: “It was found by our party in the valleys of the coast ranges as far north as Fort Lane in Oregon.” Fort Lane was on the eastern fl ank of Blackwell Hill (between Central Point and Gold Hill in Jackson County), so his description may also include the Th e lone gray pine at Tolo, near the old Fort Lane site, displays the characteristic architecture of multiple Applegate Valley. -

GRAY PINE Gray Squirrels

GRAY PINE gray squirrels. Mule and white-tailed deer browse Pinus sabiniana Dougl. ex the foliage and twigs. Dougl. Status plant symbol = PISA2 Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s Contributed By: USDA, NRCS, National Plant Data current status, such as, state noxious status, and Center wetland indicator values. Alternative Names Description General: Pine Family (Pinaceae). This native tree reaches 38 m in height with a trunk less than 2 m wide. The gray-green foliage is sparse and it has three needles per bundle. Each needle reaches 9-38 cm in length. The trunk often grows in a crooked fashion and is deeply grooved when mature. The seed cone of gray pine is pendent, 10-28 cm, and opens slowly during the second season, dispersing winged seeds. Distribution Charles Webber © California Academy of Sciences It ranges in parts of the California Floristic Province, @CalPhotos the western Great Basin and western deserts. For foothill pine, bull pine, digger pine, California current distribution, please consult the Plant Profile foothill pine page for this species on the PLANTS Web site. Uses Establishment Ethnobotanic: The seeds of gray pine were eaten by Adaptation: This tree is found in the foothill many California Indian tribes and are still served in woodland, northern oak woodland, chaparral, mixed Native American homes today. They can be eaten conifer forests and hardwood forests from 150- fresh and whole in the raw state, roasted, or pounded 1500m. into flour and mixed with other types of seeds. The seeds were eaten by the Pomo, Sierra Miwok, Extract seeds from the cones and gently rub the Western Mono, Wappo, Salinan, Southern Maidu, wings off, and soak them in water for 48 hours, drain Lassik, Costanoan, and Kato, among others. -

Conifer Communities of the Santa Cruz Mountains and Interpretive

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ CALIFORNIA CONIFERS: CONIFER COMMUNITIES OF THE SANTA CRUZ MOUNTAINS AND INTERPRETIVE SIGNAGE FOR THE UCSC ARBORETUM AND BOTANIC GARDEN A senior internship project in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS in ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES by Erika Lougee December 2019 ADVISOR(S): Karen Holl, Environmental Studies; Brett Hall, UCSC Arboretum ABSTRACT: There are 52 species of conifers native to the state of California, 14 of which are endemic to the state, far more than any other state or region of its size. There are eight species of coniferous trees native to the Santa Cruz Mountains, but most people can only name a few. For my senior internship I made a set of ten interpretive signs to be installed in front of California native conifers at the UCSC Arboretum and wrote an associated paper describing the coniferous forests of the Santa Cruz Mountains. Signs were made using the Arboretum’s laser engraver and contain identification and collection information, habitat, associated species, where to see local stands, and a fun fact or two. While the physical signs remain a more accessible, kid-friendly format, the paper, which will be available on the Arboretum website, will be more scientific with more detailed information. The paper will summarize information on each of the eight conifers native to the Santa Cruz Mountains including localized range, ecology, associated species, and topics pertaining to the species in current literature. KEYWORDS: Santa Cruz, California native plants, plant communities, vegetation types, conifers, gymnosperms, environmental interpretation, UCSC Arboretum and Botanic Garden I claim the copyright to this document but give permission for the Environmental Studies department at UCSC to share it with the UCSC community. -

Pinus Sabiniana – Gray Pine (Also Known As Foothill Pine, Digger Pine

Pinus sabiniana – gray pine (also known as foothill pine, digger pine*, bull pine, ghost pine, and grayleaf pine) It is fast growing when young and slow growing with age. It is moderately long-lived – 100 years+. It grows in an upright form to a height of 80 feet. The foliage is gray-green, lacy, fairly open and it is sometimes called the see- through pine. Native to dry, western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains and mostly the inner coast ranges. Gray Pine will grow in full or part sun and it is very drought tolerant. Its open structure gives light shade and if the bottom branches are pruned off, you can garden under it. The large seed is edible. Indians used the root fibers for baskets. Taxodium distichum – bald cypress a long-lived, pyramidal conifer which grows 50-70'+ tall. Although it looks like a needled evergreen in summer, it is deciduous ("bald" as the common name suggests) and drops its needles in the fall. The Bald Cypress grows well in wet areas, but it's also adaptable to dry areas. It can handle a wide variety of soil types and grows beautifully in either full sun or partial sun. In spring, radiant, new green needles develop. The fern-like foliage is soft. The soft, short and feathery needles turn a gorgeous cinnamon-red for autumn. Aesculus hippocastanum – horse chestnut Beautiful, 5"-12" oblong clusters of white flowers with a yellow and red tint appear in early to mid-May. This large flowering tree is perfect for large areas. -

Vegetation Mapping of Eastman and Hensley Lakes and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California

Vegetation Mapping of Eastman and Hensley Lakes and Environs, Southern Sierra Nevada Foothills, California By Sara Taylor, Daniel Hastings, Jaime Ratchford, Julie Evens, and Kendra Sikes of the 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento CA, 95816 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To Those Who Generously Provided Support and Guidance: Many groups and individuals assisted us in completing this report and the supporting vegetation map/data. First, we expressly thank an anonymous donor who provided financial support in 2010 for this project’s fieldwork and mapping in the southern foothills of the Sierra Nevada. We also are thankful of the generous support from California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW, previously Department of Fish and Game) in funding 2008 field survey work in the region. We are indebted to the following additional staff and volunteers of the California Native Plant Society who provided us with field surveying, mission planning, technical GIS, and other input to accomplish this project: Jennifer Buck, Andra Forney, Andrew Georgeades, Brett Hall, Betsy Harbert, Kate Huxster, Theresa Johnson, Claire Muerdter, Eric Peterson, Stu Richardson, Lisa Stelzner, and Aaron Wentzel. To Those Who Provided Land Access: Angela Bradley, Ranger, Eastman Lake, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Bridget Fithian, Mariposa Program Manager, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Chuck Peck, Founder, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Diana Singleton, private landowner Diane Bohna, private landowner Duane Furman, private landowner Jeannette Tuitele-Lewis, Executive Director, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Kristen Boysen, Conservation Project Manager, Sierra Foothill Conservancy Park staff at Hensley Lake, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers i This page has been intentionally left blank. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. -

Vegetation Classification, Descriptions, and Mapping of The

Vegetation Classification, Descriptions, and Mapping of the Clear Creek Management Area, Joaquin Ridge, Monocline Ridge, and Environs in San Benito and Western Fresno Counties, California Prepared By California Native Plant Society And California Department of Fish and Game Final Report Project funded by Funding Source: Resource Assessment Program California Department of Fish and Game And Funding Source: Resources Legacy Fund Foundation Grant Project Name: Central Coast Mapping Grant #: 2004-0173 February 2006 Vegetation Classification, Descriptions, and Mapping of the Clear Creek Management Area, Joaquin Ridge, Monocline Ridge, and Environs in San Benito and Western Fresno Counties, California Final Report February 2006 Principal Investigators: California Native Plant Society staff: Julie Evens, Senior Vegetation Ecologist Anne Klein, Vegetation Ecologist Jeanne Taylor, Vegetation Assistant California Department of Fish and Game staff: Todd Keeler-Wolf, Ph.D., Senior Vegetation Ecologist Diana Hickson, Senior Biologist (Botany) Addresses: California Native Plant Society 2707 K Street, Suite 1 Sacramento, CA 95816 California Department of Fish and Game Biogeographic Data Branch 1807 13th Street, Suite 202 Sacramento, CA 95814 Reviewers: Bureau of Land Management: Julie Anne Delgado, Botanist California State University: John Sawyer, Professor Emeritus TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................. 1 BACKGROUND........................................................................................................................................... -

A New Conifer Herbarium

Reprinted from Taxon 15(6): 217-218. July 1966. A NEW CONIFER HERBARIUM William B. Critchfield (Berkeley, Calif.) * At the Institute of Forest Genetics, Placerville, California *), we have recently or ganized a specialized herbarium of pines (Pinus) and firs {Abies). Incorporated in it. are the many specimens that have accumulated since the Institute was established in 1925. Like die Eddy Arboretum, the herbarium is an integral part of our research program, which is concerned with the genetic improvement of conifers native to the western United States. Interspecific hybridization and geographic variability are important parts of the program, and the herbarium is particulary useful in documen ting this research. Because we deal exclusively with coniferous materials, our techniques have been adapted to their bulky nature. For mounting specimens, we use herbarium plastic and sheets of high-grade cardboard cut to the standard size of herbarium paper. Most cones, bark, and other unmounted materials are stored in heavy-duty (0.004-inch thick) polyethylene bags. Fir cones are prevented from disintegrating by several in terconnected straps of thickened herbarium plastic. Our general pine collection includes cones, foliage, seeds, and seedlings of most of the 95 to 100 species in this genus — about 3,000 specimens in all. The regions best represented are the western United States, Mexico and Central America, and east and southeast Asia. The extensive collection of Mexican pines includes specimens collected by E. L. Little, Jr., M. Martinez, N. T. Mirov, and the 1962 North Carolina State College expedition to Mexico (publ. 1963). The newer general collection of Abies includes about 500 specimens; only the western North American firs are adequately represented in it. -

Conifers of the Sierra

California Forests: Presentation to the California Naturalists September 18, 2015 Susie Kocher, Forestry Advisor, Central Sierra [email protected] Presentation Goals • Overview of forests in California, status and threats • Familiarity with Sierra conifer species and forest types • Basic understanding of – Sierra forest ecology Interaction / growth of different species – Forest fuels reduction projects – Insects and disease 33 million acres of Forest in California • 19 million acres (57%) federal agencies (Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management National Park Service) • < 1 million acres (3%) State and local agencies (CalFire, local open space, park /water districts, land trusts • 14 million acres (40%) private ─ 5 million acres (14%) Industrial timber companies ─ 9 million acres individuals where 90% own < 50 acres Sierra Nevada Conifers • Any of various mostly needle-leaved or scale- leaved, chiefly evergreen, cone-bearing gymnospermous trees or shrubs • Pines (pinus spp.) – Needles in bundles – Seeds carried on cones that fall to ground whole – Two families are yellow and white pines • Firs (abies spp.) – Needles individually attached to stems – Cones do not fall whole to the ground Foothill pine Pinus sabiniana • Needles in bundles of 3, pale gray-green, sparse and drooping, 8 to 13 inches long • Cones large and heavy, 5-14 inches long • California Indians used its seeds, cones, bark, and buds as food, and twigs, needles, cones, and resin in basket and drum construction and medicine Ponderosa pine Pinus Ponderosa • 2-3 needles per bundle - 3 to 5 inches long • Cone bracts long and “prickly” • Orange puzzle piece bark Jeffrey pine Pinus Jeffreyi • 2-3 needles per bundle - 3 to 5 inches long • Cone stouter with bracts turned in “gentle” • Resin scent described as vanilla or butterscotch. -

Angeles National Forest

Bigcone Douglas-Fir Mapping and Monitoring Report Angeles National Forest By Michael Kauffmann1, Ratchford, Jaime2, Julie Evens3, 4 5 Lindke, Ken , and Barnes, Jason In collaboration with Diane Travis, Fuels Planner, Angeles National Forest Anton Jackson, USDA Forest Service Enterprise Program January, 2017 1. Kauffmann, Michael E., California Native Plant Society, 2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816, [email protected] 2. Ratchford, Jaime, California Native Plant Society, 2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816, [email protected] 3. Evens, Julie, California Native Plant Society, 2707 K Street, Suite 1, Sacramento, CA 95816, [email protected] 4. Lindke, Ken - Environmental Scientist, CA Dept. Fish and Wildlife, 5341 Ericson Way, Acata 95521 [email protected] 5. Barnes, Jason - GIS Analyst, 1030 C Street, Arcata, CA 95521, [email protected] Photo on cover page: Pseudostuga macrocarpa in the San Gabriel Wilderness, Angeles National Forest All photos by Michael Kauffmann unless otherwise noted All figures by Michael Kauffmann unless otherwise noted Acknowledgements: • CNPS field staff including Daniel Hastings, Josyln Curtis, and Kendra Sikes • TEAMS biological technicians including Zya Levy, Jim Dilley, and Erica Lee who helped with the field work. • TEAMS Field Operations Supervisor Jeff Rebitzke. • USDA Forest Service Southern Province Ecologist Nicole Molinari for project design considerations and re viewing drafts of the document. Special thanks to Shaun and RT Hawke, Stuart Baker, Mike Radakovich, Sylas Kauffmann and Allison Poklemba for ad- venturing into the wilds and helping with field work. Suggested citation: Kauffmann, M., J. Ratchford, J. Evens, K. Lindke, J. Barnes. 2017. Angeles National Forest: Bigcone Douglas-fir Mapping and Monitoring Report. -

How to Look at Pines

How to Look at Pines Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: multi-branched shrub single-stemmed tree Leaves: Can you fnd both scale leaves and needle leaves? Number of needles per bundle: 1 2 3 4 5 Needle length: __________ Foliage: drooping or not drooping Female Cones: Persistent on tree?: yes or no Cone symmetry: asymmetrical symmetrical Cone prickle: present absent Cone length: __________ Seeds: wing longer than seed or wing shorter than seed Other Notable Features: Key to California’s Commonly Cultivated Pines 1. Most bundles (fascicles) with 2 needles (occasionally with 3 needles) 2. Mature plant a shrub or multi branched small tree—Mugo Pine (P. mugo) 2’ Mature plant a large, single-stemmed tree 3. Bark on old trunk breaking into large plates, some orangish in color, seed wing shorter than seed, tree crown rounded, umbrella-like—Italian Stone Pine (P. pinea) 3’ Bark on old trunk breaking into small or elongated plate, all brown or gray in color, seed wing longer than seed, tree shape varying 4. Cones persisting for years (old branches with many cones) 5. Needles mostly less than 3 inches long, cones recurved on stems—Aleppo Pine (P. halepensis) 5’ Needles mostly 3 inches long or more, cones erect to forward pointing on stems— Mondell Pine (P. eldarica) 4’ Cones falling at maturity (old cones not found on branches) 6. Twigs ofen glaucous, buds chestnut brown, bark in upper part of tree orangish- red, faky—Japanese Red Pine (P. densifora) 6’ Twigs not glaucous, buds conspicuously white, bark dark brown with deep longitudinal fssures—Japanese Black Pine (P. -

Technical Memorandum 13-1

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM 13-1 Native American Traditional Cultural Properties Yuba River Development Project FERC Project No. 2246 December 2012 ©2012, Yuba County Water Agency All Rights Reserved Yuba County Water Agency Yuba River Development Project FERC Project No. 2246 TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM 13-1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Yuba County Water Agency (YCWA) conducted a Native American Traditional Cultural Properties (TCP) Study for the Yuba River Development Project (Project), Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) Project Number 2246, from March 2009 through July 2012. The Area of Potential Effects (APE) encompassed 4,306 acres, including the FERC Project Boundary and a 200-foot radius surrounding New Bullards Bar Reservoir. YCWA requested the State Historic Preservation Officer’s (SHPO) concurrence on the APE in a letter dated March 21, 2012, and received SHPO’s concurrence in a letter dated April 19, 2012, in accordance with 36 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Section (§) 800. For relicensing of the Project, FERC designated YCWA as FERC’s non-federal representative for purposes of consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, and the implementing regulations found in 36 CFR § 800.2(c)(4). YCWA conducted several consultation meetings with tribes and agencies beginning in 2009 and continuing into 2012. YCWA, tribes, and agencies collaboratively developed study proposals and selection of the TCP Study ethnographer, Albion Environmental, Inc. Invitations to participate in each meeting were sent to tribal representatives, FERC, SHPO, Plumas National Forest, and Tahoe National Forest. Most of these individuals and organizations participated in the meetings. On October 19, 2011, YCWA convened a meeting of tribal groups and agencies to introduce members of YCWA’s team, discuss the FERC-approved study, and to initiate field consultation with the tribes. -

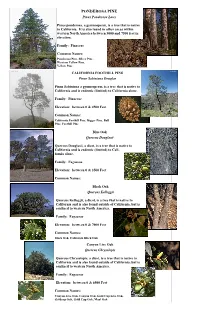

Trees-Shrubs.Pdf

PONDEROSA PINE Pinus Ponderosa Laws Pinus ponderosa, a gymnosperm, is a tree that is native to California. It is also found in other areas within western North America between 3000 and 7500 feet in elevation. Family: Pinaceae Common Names: Ponderosa Pine, Silver Pine, Western Yellow Pine, Yellow Pine CALIFORNIA FOOTHILL PINE Pinus Sabiniana Douglas Pinus Sabiniana a gymnosperm, is a tree that is native to California and is endemic (limited) to California alone. Family: Pinaceae Elevation: between 0 & 4500 Feet Common Names: California Foothill Pine, Digger Pine, Bull Pine, Foothill Pine Blue Oak Quercus Douglasii Quercus Douglasii, a dicot, is a tree that is native to California and is endemic (limited) to Cali- fornia alone. Family: Fagaceae Elevation: between 0 & 3500 Feet Common Names: Black Oak Quercus Kelloggii Quercus Kelloggii, a dicot, is a tree that is native to California and is also found outside of California, but is confined to western North America. Family: Fagaceae Elevation: between 0 & 7000 Feet Common Names: Black Oak, California Black Oak Canyon Live Oak Quercus Chrysolepis Quercus Chrysolepis, a dicot, is a tree that is native to California and is also found outside of California, but is confined to western North America. Family: Fagaceae Elevation: between 0 & 6500 Feet Common Names: Canyon Live Oak, Canyon Oak, Gold Cup Live Oak, Goldcup Oak, Gold Cup Oak, Maul Oak Valley Oak Quercus Lobata Quercus lobata, a dicot, is a tree that is native to California and is endemic (limited) to California Alone. Family: Fagaceae Elevation: between 0 & 2000 Feet Common Names: California White Oak, Valley Oak White Alder Alnus Rhombifolia Alnus Rhombifolia, a dicot, is a tree that is native to California and is also found outside of California, but is confined to Western North America.