Holy Island Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gateway West Local Amenities

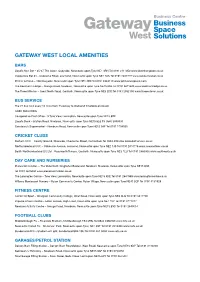

GATEWAY WEST LOCAL AMENITIES BARS Lloyd’s No1 Bar – 35-37 The Close, Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3RN Tel 0191 2111050 www.jdwetherspoon.co.uk Osbournes Bar 61 - Osbourne Road, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 2AN Tel 0191 2407778 www.osbournesbar.co.uk Pitcher & Piano – 108 Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3DX Tel 0191 2324110 www.pitcherandpiano.com The Keelman’s Lodge – Grange Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NL Tel 0191 2671689 www.keelmanslodge.co.uk The Three Mile Inn – Great North Road, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 2DS Tel 0191 2552100 www.threemileinn.co.uk BUS SERVICE The 22 bus runs every 10 mins from Throckley to Wallsend timetable enclosed CASH MACHINES Co-operative Post Office - 9 Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Lloyd’s Bank – Station Road, Newburn, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8LS Tel 0845 3000000 Sainsbury’s Supermarket - Newburn Road, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 9AF Tel 0191 2754050 CRICKET CLUBS Durham CCC – County Ground, Riverside, Chester-le-Street, Co Durham Tel 0844 4994466 www.durhamccc.co.uk Northumberland CCC – Osbourne Avenue, Jesmond, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 1JS Tel 0191 2810775 www.newcastlecc.co.uk South Northumberland CC Ltd – Roseworth Terrace, Gosforth, Newcastle upon Tyne NE3 1LU Tel 0191 2460006 www.southnort.co.uk DAY CARE AND NURSERIES Places for Children – The Waterfront, Kingfisher Boulevard, Newburn Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8NZ Tel 0191 2645030 www.placesforchildren.co.uk The Lemington Centre – Tyne View, Lemington, Newcastle upon Tyne NE15 8DE Tel 0191 2641959 -

Island Adventure 5A 14.5 Miles (23.3Km) - One Way

Island Adventure 5a 14.5 miles (23.3km) - one way Berwick-upon-Tweed to Holy Island (Lindisfarne) Lidisfarne Castle. Photo: © Ian Scott © Crown copyright 2019 OS 0100049048 One of the most popular rides in Northumberland; enjoy an START/FINISH 0m 1m inspirational ride from the beautiful town of Berwick‐upon‐Tweed to the historic and atmospheric Holy Island or Lindisfarne. 0km 1km 2km This route has some rough track sections so is not suitable for a road bike. Start/ End point car park: Castle Gate, Parade and Quay Wall car park, Berwick‐upon‐Tweed. Cocklawburn Beach and Spittal Distance: If you don't want to ride the whole distance, shorter options are: Berwick‐upon‐Tweed to Cocklawburn Beach 3.5 miles (one way) Cocklawburn Beach to Holy Island Causeway 7.5 miles (one way) Holy Island Causeway to Holy Island village 3.5 miles (one way) Bike hire: yes, in Berwick Toilets: available in Berwick and on Lindisfarne Where to eat: lots of places to eat and drink in Berwick, Spittal and on Lindisfarne itself Things to look out for: geology of coastline, Lindisfarne Castle Make a day of it: Berwick Barracks, Berwick Town Walls, Lindisfarne Castle, Lindisfarne Priory START/FINISH More information at: www.visitberwick.com www.visitnorthumberland.com/holy‐island www.northumberlandcoastaonb.org/ Holy Island is cut off twice a day from the mainland by fast moving tides. PLEASE CHECK THE CAUSEWAY TIMES BEFORE YOU START www.holy‐island.info/lindisfarnecastle/2019 1 Cycle map: Scale 1:50 000 - 2cm to 1km - 1 /4 inches to 1 mile based on Ordnance Survey 1:50 000 scale mapping. -

Landscape Sensitivity and Capacity Study August 2013

LANDSCAPE SENSITIVITY AND CAPACITY STUDY AUGUST 2013 Prepared for the Northumberland AONB Partnership By Bayou Bluenvironment with The Planning and Environment Studio Document Ref: 2012/18: Final Report: August 2013 Drafted by: Anthony Brown Checked by: Graham Bradford Authorised by: Anthony Brown 05.8.13 Bayou Bluenvironment Limited Cottage Lane Farm, Cottage Lane, Collingham, Newark, Nottinghamshire, NG23 7LJ Tel: +44(0)1636 555006 Mobile: +44(0)7866 587108 [email protected] The Planning and Environment Studio Ltd. 69 New Road, Wingerworth, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, S42 6UJ T: +44(0)1246 386555 Mobile: +44(0)7813 172453 [email protected] CONTENTS Page SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ i 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 Background ............................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Objectives of the Study ........................................................................................ 2 Key Views Study ........................................................................................................................ 3 Consultation .............................................................................................................................. 3 Format of the Report ............................................................................................................... -

53652 02 MG Lime Kiln Leaflet 8Pp:Layout 2

Slaked lime. What happened to the industry? The lime kilns today Discover What was To make clay soils more By the 1880s the lime trade was Today the lime kilns stand as a monument to the industrial era in a workable and to neutralise in decline and by 1900 seems to place not usually associated with such activity. In recent times, work the burnt lime acid soil.** have ceased production. Activity has been carried out by the National Trust which has involved parts of To make whitewash, had only been sporadic through the kilns being reinforced and altered. This is most evident around the used for? mortar and plaster.** the final years of the nineteenth The Castle Point south western pot, where the brick walls have been removed from century. On the 17th September above the draw arches and concrete lintels have been installed. Burnt lime from Lindisfarne was To destroy odours in mass probably used primarily in burials.** 1883, the Agnes left the Staithes; In 2010, the first phase of important improvements to access and agriculture. The alkali-rich slaked the last ship to depart Holy interpretation began. The old fences were improved to prevent sheep To make bleaching powder, lime kilns lime was perfect for neutralising Island laden with lime, This ship, a disinfectant.* from gaining access to the kilns, and a floor was laid in the central acidic soil and so improving along with others of Nicoll’s passageway. A new public access gate was also installed. fertility. It is also likely that some fleet, did return in the next few To make caustic soda used to Funding for this project came from National Trust Property Raffle sales of the slaked lime was used in make soap.* years but only, it seems, to in the Castle, Gift Aid on Entry money from visitors. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

Northumberland Coast Path

Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes Northumberland Coast Path The Northumberland Coast is best known for its sweeping beaches, imposing castles, rolling dunes, high rocky cliffs and isolated islands. Amidst this striking landscape is the evidence of an area steeped in history, covering 7000 years of human activity. A host of conservation sites, including two National Nature Reserves testify to the great variety of wildlife and habitats also found on the coast. The 64miles / 103km route follows the coast in most places with an inland detour between Belford and Holy Island. The route is generally level with very few climbs. Mickledore - Walking Holidays to Remember 1166 1 Walking Holidays in Britain’s most Beautiful Landscapes t: 017687 72335 e: [email protected] w: www.mickledore.co.uk Summary on the beach can get tiring – but there’s one of the only true remaining Northumberland Why do this walk? usually a parallel path further inland. fishing villages, having changed very little in over • A string of dramatic castles along 100 years. It’s then on to Craster, another fishing the coast punctuate your walk. How Much Up & Down? Not very much village dating back to the 17th century, famous for • The serene beauty of the wide open at all! Most days are pretty flat. The high the kippers produced in the village smokehouse. bays of Northumbrian beaches are point of the route, near St Cuthbert’s Just beyond Craster, the route reaches the reason enough themselves! Cave, is only just over 200m. imposing ruins of Dunstanburgh Castle, • Take an extra day to cross the tidal causeway to originally built in the 14th Century by Holy Island with Lindisfarne Castle and Priory. -

Assessing the Past the Following List Contains Details of Archaeological

Assessing the Past The following list contains details of archaeological assessments, evaluations and other work carried out in Northumberland in 2013-2015. They mostly result from requests made by the County Archaeologist for further research to be carried out ahead of planning applications being determined. Copies of these reports are available for consultation from the Archaeology Section at County Hall and some are available to download from the Library of Unpublished Fieldwork held by the Archaeology Data Service. Event Site Name Activity Organisation Commissioned by Start Parish No 15115 East House Farm, Guyzance, DESK BASED Wessex Archaeology Knight Frank LLP 2013 ACKLINGTON Northumberland: Archaeological Impact ASSESSMENT Assessment 15540 Lanton Quarry Phase 6 archaeological STRIP MAP AND Archaeological Lafarge Tarmac Ltd 2013 AKELD excavation SAMPLE Research Services 15340 Highburn House, Wooler WATCHING BRIEF Archaeological Services Sustainable Energy 2013 AKELD Durham University Systems Ltd 15740 Archaeological assessment of Allenheads DESK BASED Vindomora Solutions The North Pennines 2013 ALLENDALE Lead Ore Works and associated structures, ASSESSMENT AONB Partnership as Craigshield Powder House, Allendale part of the HLF funded Allen Valleys Partnership Project 15177 The Dale Hotel, Market Place, Allendale, EVALUATION Wardell Armstrong Countryside Consultants 2013 ALLENDALE Northumberland: archaeological evaluation 15166 An Archaeological Evaluation at Haggerston TRIAL TRENCH Pre-Construct Prospect Archaeology 2013 ANCROFT -

HOLY ISLAND, ALNWICK & the KINGDOM of NORTHUMBRIA Please Note That This Tour Includes a Crossing Over to Holy Island Via A

HOLY ISLAND, ALNWICK & THE KINGDOM OF NORTHUMBRIA Please note that this tour includes a crossing over to Holy Island via a causeway. Sometimes this route will be taken in reverse, depending on tidal timings. After leaving the city we travel through a county called East Lothian, full of rich farmland with a range of hills away to the right, the Lammermuirs. We pass by the town of Musselburgh, home of the world’s oldest golf course – it dates back to 1672 and has been the venue for the Open Championship six times. At Prestonpans a battle took place in 1745 between a government army and one led by a famous figure in Scottish history, Bonnie Prince Charlie. This was the fifth and last Jacobite Uprising which were attempts to regain the throne for the deposed House of Stewart. All the uprisings ultimately failed but this battle was won by the Jacobites. At this point you will see the Firth of Forth over to the left. This is an inlet of the North Sea that separates Britain from mainland Europe. Soon we drive inland and pass Haddington on our right, the county town for East Lothian and a pleasant market town. Soon we pass Dunbar away to our left. It has a ruined castle overlooking the harbour. There were two battles fought close to Dunbar in 1296 & 1650, both defeats for the Scots. A man called John Muir was born in Dunbar in 1838 - he emigrated to the USA aged 11 with his family and was to become a world-famous naturalist, environmentalist, explorer & geologist – he is known as the ‘Father of World Conservation’. -

Northern Counties Photographic Federation a Member Federation of the Photographic Alliance of Great Britain

Northern Counties Photographic Federation A Member Federation of the Photographic Alliance of Great Britain Report on the 2015 NCPF Annuals Club Competition Competitions Organiser: Cliff Banks ARPS EFIAP Prints Officer: John Twizell PDI Officer: Cliff Banks ARPS EFIAP Portfolio Secretary: Gerry Adcock. ARPS Judges for the 2015 Competition Open Sections: Jim Hartje, ARPS, DPAGB,APAGB, EFIAP Peter Rees, FRPS, MPAGB, EFIAP/p. Vince Rooker, DPAGB, APAGB, EFIAP. Beginners Section David Ord. PAGB Alliance Selection Jane Black, ARPS, FPSA, Hon. PAGB. (Tynemouth PS) Leo Palmer, FRPS, FPSA, GMPSA, EFIAP, APAGB. (Hexham PS) David Stout, EFIAP, DPAGB. (Ryton CC) Portfolio Selection Malcolm Blenkey. (Saltburn PS) Angela Ellis. (Durham PS) Gerry Adcock. ARPS (Hexham PS) May we begin by thanking the judges who did a magnificent job over a two day event and also the helpers who made the event take place successfully. Numbers info for the Print entry for 2015 Annuals Total No Clubs submitting entry`s: - 32 Total No Boxes received:- 35 Total No Prints for :- Bewick 567 Corder 434 Chalmers 79 Grand Total :- 1080 We are a total of 102 prints down from last year Bewick 78 Corder 19 Chalmers 5 Numbers info for the PDI entry for 2015 Annuals Total No Clubs submitting entry`s :- 32 Total No PDI for :- Myles Audas Trophy 776 Jane Black Trophy 109 Grand Total :- 885 We are up on the PDI entry Regards John Twizell and Cliff Banks Results of the Corder Trophy For the Best Club Entry of Monochrome Prints Club Score Position Carlisle CC 77 1st Morton CC 76 2nd Gateshead -

Berwick-Upon-Tweed Poor Law Union. Board of Guardians Correspondence Book GBR 78

Berwick-upon-Tweed Poor Law Union. Board of Guardians correspondence book GBR 78. GBR 78 Volume of incoming correspondence from the Poor Law Board 1856-1858 to the Berwick-upon-Tweed Poor Law Union. The Poor Law Board reference numbers, when included, are shown at the end of each entry. GBR 78/1-2 [One leaf torn out. Illegible.] Jan. 1856 GBR 78/3-4 Attention is drawn to the sale of a piece of land, mentioned in letter 11 Jan. 1856 from the Board 29 October 1855, called the “Burrs” in the Parish of Berwick. The Board wish to be supplied with a reply to their letter. 20864/55 GBR 78/5 Reference to letter of 3 January 1856 forwarding copy of letter [not 19 Jan. 1856 enclosed] received by the Board from the Committee of Council of Education respecting the apparatus for the infant school at the Workhouse. 2168/56 GBR 78/6-8 Letter from the Privy Council Office to the Poor Law Board forwarding 16 Jan. 1856 extract from a communication received from T B Browne, H M Inspector, stating that the present infant schoolroom is not fit for purpose, and the apparatus should not be provided until the new schoolroom is completed. 2168/56 GBR 78/9-10 Letter acknowledging that of 21 January 1856 regarding the proposed 26 Jan. 1856 exchange of land between the Burial Board for the Parish of Berwick and the Parish Officers. 2600/56 GBR 78/11-12 Letter acknowledging that of 22 January respecting proposed alteration 30 Jan. 1856 in the dietary for the inmates of the Union Workhouse. -

Norham and Islandshire Petty Sessions Register 1915 – 1923 ( Ref : Ps 6/1)

NORHAM AND ISLANDSHIRE PETTY SESSIONS REGISTER 1915 – 1923 ( REF : PS 6/1) PAGE DATE OF SENTENCE NO & OFFENCE/ COMPLAINANT DEFENDANT OFFENCE PLEA INC. FINES NOTES CASE DATE OF AND COSTS * NO TRIAL PS 6/1 7 April 1915 Ellen DIXON Thomas SMITH Application in Parents Costs £1 0s 6d page1/ Norham West Galagate Farm Bastardy, child Admitted 2s 6d per week till case Mains Servant born 25 May child attains 14 no.13 Single Woman 1914; Male years of age PS 6/1 27 March 1915 Sergeant John R Robert HARRISON Riding bicycle at No Fine 5s, Berwick Advertiser 9 April 1915, page 4, col 4. page1/ 7 April 1915 GRAY Twizel night with light, appearance allowed till 5 May Twizel Railway Station. Was riding at 10.20pm on highway case Cycle Fitter. in Cornhill Parish next, to pay or 5 between Cornhill and Coldstream Bridge. When questioned no.14 Aged 18 days in prison by PC SHORT, defendant said his lamp would not burn. PS 6/1 6 March 1915 Sergeant John R Ellen TAIT Drunk and No Fine 5s, Berwick Advertiser 9 April 1915, page 4, col 4 page1/ 7 April 1915 GRAY Scremerston disorderly at appearance allowed till 5 May Ellen TAIT of Richardson Steads was found by Sergeant case Widow Scremerston in next, to pay or 5 ELLIOTT at 5.30, very drunk, shouting and using bad no.15 Ancroft Parish days in prison language and annoying passers-by. PS 6/1 7 April 1915 Applicant: William Application for two Fees 5s. Granted. Berwick Advertiser 9 April 1915, page 4, col 4, Licence page1/ LILLICO Occasional granted to Mrs LILLICO, Nags Head, Berwick. -

Norham Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

Norham Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey The Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey Project was carried out between 1995 and 2008 by Northumberland County Council with the support of English Heritage. © Northumberland County Council and English Heritage 2009 Produced by Rhona Finlayson, Caroline Hardie and David Sherlock 1995-7 Revised by Alan Williams 2007-8 Strategic Summary by Karen Derham 2008 Planning policies revised 2010 All the mapping contained in this report is based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationary Office. © Crown copyright. All rights reserved 100049048 (2009) All historic mapping contained in this report is reproduced courtesy of the Northumberland Collections Service unless otherwise stated. Copies of this report and further information can be obtained from: Northumberland Conservation Development & Delivery Planning Economy & Housing Northumberland County Council County Hall Morpeth NE61 2EF Tel: 01670 620305 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.northumberland.gov.uk/archaeology Norham 1 CONTENTS PART ONE: THE STORY OF NORHAM 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Project Background 1.2 Location, Topography and Geology 1.3 Brief History 1.4 Documentary and Secondary Sources 1.5 Cartographic Sources 1.6 Archaeological Evidence 1.7 Protected Sites 2 PREHISTORIC AND ROMAN 2.1 Prehistoric Period 2.2 Roman Period 3 EARLY MEDIEVAL 3.1 Monastery and Church 3.2 The Ford 3.3 The Village 4 MEDIEVAL 4.1 Norham Castle 4.2 Mill and Aqueduct 4.3 Church of St Cuthbert