New Algiers Terreform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keepin' Your Head Above Water

Know Your Flood Protection System Keepin’ Your Head Above Water Middle School Science Curriculum Published by the Flood Protection Authority – East floodauthority.org Copyright 2018 Keepin’ Your Head Above Water: Know Your Flood Protection System PREFACE Purpose and Mission Our mission is to ensure the physical and operational integrity of the regional flood risk management system in southeastern Louisiana as a defense against floods and storm surge from hurricanes. We accomplish this mission by working with local, regional, state, and federal partners to plan, design, construct, operate and maintain projects that will reduce the probability and risk of flooding for the residents and businesses within our jurisdiction. Middle School Science Curriculum This Middle School Science Curriculum is part of the Flood Protection Authority – East’s education program to enhance understanding of its mission. The purposes of the school program are to ensure that future generations are equipped to deal with the risks and challenges associated with living with water, gain an in-depth knowledge of the flood protection system, and share their learning experiences with family and friends. The curriculum was developed and taught by Anne Rheams, Flood Protection Authority – East’s Education Consultant, Gena Asevado, St. Bernard Parish Public Schools’ Science Director, and Alisha Capstick, 8th grade Science Teacher at Trist Middle School in Meraux. La. The program was encouraged and supported by Joe Hassinger, Board President of the Flood Protection Authority – East and Doris Voitier, St. Bernard Parish Public Schools Superintendent. The curriculum was developed in accordance with the National Next Generation Science Standards and the Louisiana Department of Education’s Performance Expectations. -

New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina. II: the Central Region and the Lower Ninth Ward

New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina. II: The Central Region and the Lower Ninth Ward R. B. Seed, M.ASCE;1; R. G. Bea, F.ASCE2; A. Athanasopoulos-Zekkos, S.M.ASCE3; G. P. Boutwell, F.ASCE4; J. D. Bray, F.ASCE5; C. Cheung, M.ASCE6; D. Cobos-Roa7; L. Ehrensing, M.ASCE8; L. F. Harder Jr., M.ASCE9; J. M. Pestana, M.ASCE10; M. F. Riemer, M.ASCE11; J. D. Rogers, M.ASCE12; R. Storesund, M.ASCE13; X. Vera-Grunauer, M.ASCE14; and J. Wartman, M.ASCE15 Abstract: The failure of the New Orleans regional flood protection systems, and the resultant catastrophic flooding of much of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, represents the most costly failure of an engineered system in U.S. history. This paper presents an overview of the principal events that unfolded in the central portion of the New Orleans metropolitan region during this hurricane, and addresses the levee failures and breaches that occurred along the east–west trending section of the shared Gulf Intracoastal Waterway/ Mississippi River Gulf Outlet channel, and along the Inner Harbor Navigation Channel, that affected the New Orleans East, the St. Bernard Parish, and the Lower Ninth Ward protected basins. The emphasis in this paper is on geotechnical lessons, and also broader lessons with regard to the design, implementation, operation, and maintenance of major flood protection systems. Significant lessons learned here in the central region include: ͑1͒ the need for regional-scale flood protection systems to perform as systems, with the various components meshing well together in a mutually complementary manner; ͑2͒ the importance of considering all potential failure modes in the engineering design and evaluation of these complex systems; and ͑3͒ the problems inherent in the construction of major regional systems over extended periods of multiple decades. -

2015 Awards Finalists

Press Club of New Orleans 2015 Awards Finalists SPORTS FEATURE - TV Sean Fazende WVUE-TV Home Patrol Garland Gillen WVUE-TV Changing the Game Tom Gregory WLAE-TV Flyboarding: The New Extreme Sport SPORTS ACTION VIDEOGRAPHY Adam Copus WWL-TV Boston Marathon Runners Edwin Goode WVUE-TV Saints vs. 49ers Carlton Rahmani WGNO-TV Ivana Coleman - Boxer SPORTS SHOW William Hill WLAE-TV Inside New Orleans Sports Doug Mouton, Danny Rockwell WWL-TV Fourth Down on Four Staff WVUE-TV FOX 8 Live Tailgate - Detroit Lions SPORTSCAST - TV Sean Fazende WVUE-TV Fox8 Sports at 10pm Doug Mouton WWL-TV Eyewitness Sports Chad Sabadie, John Bennett WVUE-TV Fox8 Sports at 10pm SPORTS STORY - WRITING Larry Holder NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune Seattle Seahawks obliterate Peyton Manning, Denver Broncos 43-8 in Super Bowl 2014 Randy Rosetta NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune LSU toughs out a 2-0 pitchers' duel win over Florida for the 2014 SEC Tournament crown Lyons Yellin WWL-TV Saints embarrassed in 41-10 home loss SPORTS FEATURE - WRITING Thomas Leggett Louisiana Health and Fitness Magazine The Sailing Life Randy Rosetta NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune Juggling life as an active-duty Marine and a LSU football player is a rewarding challenge for Luke Boyd Ramon Antonio Vargas New Orleans Advocate Still Running: Khiry Robinson's ability on the football field helped him escape his troubles off it SPORTS BLOG - INTERNET Larry Holder NOLA.com | The Times-Picayune Larry Holder’s Entries Chris Price Biz New Orleans The Pennant Chase Staff Bourbon Street Shots, LLC Bourbon Street -

Algiers Point Historic District

CITY OF NEW ORLEANS Historic District Landmarks Commission Algiers Point Historic District Designated 1993 Jurisdiction: New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission The Algiers Point Historic District is bounded by the curve of the Mississippi River on two sides and by Atlantic and Newton Streets on the other two. Named for a navigation bend in the Mississippi River, The town of Algiers was annexed by the City of New Algiers Point was an independent municipality for 30 years Orleans on March 14, 1870 and continued to develop from its founding, and even today it retains a quiet small into the early 20th century. Martin Behrman, the longest town atmosphere. Bordered by the Mississippi River on serving mayor of New Orleans (1904-1920, 1925-1926), two sides, and lying directly across the river from the was an Algiers native who preferred his home office at 228 Vieux Carré, Algiers Point continued to develop as a largely Pelican Avenue to City Hall. independent town well into the 20th century. Some of the early buildings from the 1840s still exist Algiers Point’s economic origins began in a boatyard today, but the District is dominated by buildings in the established in 1819 by Andre Seguin. The Algiers-Canal Greek Revival, Italianate and Victorian styles, reflecting Street Ferry began in 1827 and has been in continuous Algiers Point’s period of greatest growth and development operation ever since. Shipbuilding, repair and other from 1850 to 1900. A devastating fire in 1895 destroyed riverfront endeavors flourished, and in 1837 a dry dock, hundreds of buildings in Algiers, and replacements were said to be the first on the Gulf Coast, was established built in the styles of the time. -

Chapter 3: the Context: Previous Planning and the Charter Amendment

Volume 3 chapter 3 THE CONTEXT: PREVIOUS PLANNING AND THE CHARTER AMENDMENT his 2009–2030 New Orleans Plan for the 21st Century builds on a strong foundation of previous planning and a new commitment to strong linkage between planning and land use decision making. City Planning Commission initiatives in the 1990s, the pre-Hurricane Katrina years, and the neighborhood-based recovery plans created after Hurricane Katrina inform this long-term Tplan. Moreover, the City entered a new era in November 2008 when voters approved an amendment to the City Charter that strengthened the relationship between the city’s master plan, the comprehensive zoning ordinance and the city’s capital improvement plan, and mandated creation of a system for neighborhood participation in land use and development decision-making—popularly described as giving planning “the force of law.” A Planning Districts For planning purposes, the City began using a map in 1970 designating the boundaries and names of 73 neighborhoods. When creating the 1999 Land Use Plan, the CPC decided to group those 73 neighborhoods into 13 planning districts, using census tract or census block group boundaries for statistical purposes. In the post-Hurricane Katrina era, the planning districts continue to be useful, while the neighborhood identity designations, though still found in many publications, are often contested by residents. This MAP 3.1: PLANNING DISTRICTS Lake No 2 Lake Pontchartrain 10 Michou d Canal Municipal Yacht Harbor 9 6 5 Intracoastal W aterway Mississippi River G ulf O utlet 11 Bayou Bienvenue 7 l 4 bor r Cana Ha l a v nner Na I 8 11 10 1b 9 6 1a Planning Districts ¯ 0 0.9 1.8 3.6 0.45 2.7 Miles 3 2 12 13 Mississippi River master plan uses the 13 planning districts as delineated by the CPC. -

Redundant Hydraulic and Control System at the Seabrook Gate Complex, New Orleans, LA

Redundant Hydraulic and Control System at the Seabrook Gate Complex, New Orleans, LA Robert Ferrara, President Thomas Behling, Systems Engineer Abstract The Seabrook Floodgate complex utilizes a 95-foot opening sector gate flanked by two 50-foot opening vertical lift gates that tie into T walls connecting to the existing levee system surrounding the city. The project is located at the northern end of the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC), near Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans, Louisiana. The project was constructed for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The major objective of the project was to work in tandem with the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Surge Barrier on the Gulf Overhead view of sector and lift gates at Intercoastal Waterway at Lake Borgne to block storm surge from Seabrook Gate Complex Lake Borgne and Lake Pontchartrain during storm events. The USACE required that the gates provide 100-year-level of protection against the 1 percent exceedance, meaning +16.0 feet level coverage for all gates. The lift gates at the Seabrook complex are driven by hydraulic systems integrated with closed loop controls for controlled motion. Six different hydraulic power units in conjunction with eight separate remote control stations and consoles and an integrated redundant control drive the gates to required storm position. Introduction The Seabrook Floodgate Complex is located at the mouth of the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal, also called the Industrial Canal, at Lake Pontchartrain. Alberici Constructors were selected to engineer, construct, install, commission and, for the 2012 hurricane season, operate the gate. The original design had only one sector gate set at the complex. -

Federal Register/Vol. 75, No. 224/Monday, November 22, 2010

71142 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 224 / Monday, November 22, 2010 / Notices All RAC meetings are open to the ALASKA Chaco Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor Ovens MPS), Chalan Josen Milagro St., public. The public may present written Skagway-Hoonah-Angoon comments to the RAC. Each formal RAC Agat, 10000967 Windfall Harbor CCC Shelter Cabin, Cruz Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor Ovens meeting will also have time allocated for Admiralty Island National Monument, hearing public comments. Depending on MPS), Route 16, Barrigada, 10000966 Angoon, 95001299 Flores Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor the number of persons wishing to Ovens MPS), Matcella Dr., Agana Heights, comment and time available, the time [FR Doc. 2010–29286 Filed 11–19–10; 8:45 am] BILLING CODE 4312–51–P 10000965 for individual oral comments may be Jinaspan Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor limited. Ovens MPS), Beach Rd., Andersen AFB, FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Yigo, 10000968 David Abrams, Western Montana Paulino Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor National Park Service Ovens MPS), Afgayan Bay, Bear Rock Ln., Resource Advisory Council Coordinator, Inarajan, 10000971 Butte Field Office, 106 North Parkmont, Quan Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor Ovens Butte, Montana 59701, telephone 406– National Register of Historic Places; Notification of Pending Nominations MPS), J.C. Santos St., Piti, 10000970 533–7617. Won Pat Outdoor Oven, (Guam’s Outdoor and Related Actions 2280–665 Ovens MPS), Between 114 and 126 Richard M. Hotaling, Mansanita Ct., Sinajana, 10000969 District Manager, Western Montana District. Nominations for the following [FR Doc. 2010–29328 Filed 11–19–10; 8:45 am] properties being considered for listing ILLINOIS BILLING CODE 4310–DN–P or related actions in the National Champaign County Register were received by the National Mattis, George and Elsie, House, 900 W Park Park Service before October 23, 2010. -

Download New Orleans Jazz Tour #1

NEW ORLEANS JAZZ TOUR (#1) RIDE THE CANAL STREET/ALGIERS POINT FERRY FROM THE FRENCH QUARTER ACROSS THE MIGHTY MISSISSPPI RIVER TO ALGIERS “OVER DA RIVER” - TO HISTORIC ALGIERS TAKE A FREE SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR, AND VISIT THE FORMER HOMES OF ALGIERS’ JAZZ MUSICIANS, THE VENUES THEY PLAYED IN, AND THE ROBERT E. NIMS JAZZ WALK OF FAME, AND GET THE BEST VIEW OF NEW ORLEANS’ SKYLINE COPYRIGHT © 2016, KEVIN HERRIDGE www.risingsunbnb.com Jazz musicians of the 1920s referred to Algiers as “over da river” or the “Brooklyn of the South,” the latter for its proximity to New Orleans as compared to New York and Brooklyn, both separated by a river. This tour concentrates on the Algiers Point neighborhood, that has a long, rich history of African American, French, Spanish, German, Irish, and Italian/Sicilian residents. Algiers, the second oldest neighborhood in New Orleans after the French Quarter, was the site of the slave holding areas, newly arrived from Africa, the powder magazine, and slaughterhouse of the early 18th century. John McDONOGH, the richest man, and largest landowner in New Orleans, lived here. Algiers was famous countrywide in the African American communities for its “Voodoo” and “Hoodoo” practitioners, and is celebrated in songs on this subject. The earliest bands containing Algiers’ musicians included the Pickwick Brass Band (1873-1900s), the Excelsior Brass Band (1880-1928), Jim DORSEY’s Band (1880s), Prof. MANETTA’s String Band (1880s), BROWN’s Brass Band of McDonoghville (1880s), and Prof. A. L. TIO’s String Band (aka the Big Four) (1880s), the Pacific Brass Band (1900-1912), and Henry ALLEN’s Brass Band (1907-1940s). -

Port NOLA PIER Plan

Port NOLA PIER Plan DRAFT Port Inner Harbor Economic Revitalization Plan (PIER Plan) DRAFT February 2020 DRAFT FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CEO Together with the Board of Commissioners of the Port of New Orleans, I am pleased to share the Port Inner Harbor Economic Revitalization Plan (PIER Plan) — a collaborative vision to revitalize the Inner Harbor District, increase commercial activity and create quality jobs for area residents. The Port NOLA Strategic Master Plan, adopted in 2018, laid out a bold vision for the next 20 years and a roadmap for growth that identified a need for regional freight-based economic development. This planning effort provided the framework for the PIER Plan. Brandy D. Christian President and CEO, Evolution in global shipping trends, changes in investment Port of New Orleans and New Orleans Public Belt Railroad strategies and multiple natural disasters have left the Port’s Corporation Inner Harbor in need of a new plan that aligns with our strategic vision and supports our economic mission. Port NOLA’s role as a port authority is to plan, build, maintain and support the infrastructure to grow jobs and economic opportunitiesDRAFT related to trade and commerce. We know that revitalization and future development cannot be done in a vacuum, so collaboration is at the core of the PIER Plan as well. True to our values, we engaged and worked with a diverse range of stakeholders in the process — including government agencies, industry, tenants, and neighboring communities as hands-on, strategic partners. The PIER Plan sets a course for redevelopment and investment in the Inner Harbor that reverberates economic prosperity beyond Port property and throughout the entire region. -

The Stories of Five Communities

SURVIVING CANCER ALLEY The Stories of Five Communities Report supported by the Climate Advocacy Lab CANCER ALLEY The Mississippi River Chemical Corridor produces one-fifth of the United States' petrochemicals and transformed one of the poorest, slowest-growing sections of Louisiana into working class communities. Yet this growth has not come without a cost: the narrow corridor absorb more toxic substances annually than do most entire states.1 An 85-mile stretch along the corridor, infamously known as "Cancer Alley," is home to more than 150 heavy industrial facilities, and the air, water, and soil along this corridor are so full of carcinogens and mutagens that it has been described as a "massive human experiment."2 According to the Centers for Disease Control, Louisiana has consistently ranked among the states with the highest rates of cancer. Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping by the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice not only shows a correlation between industrial pollution and race in nine Louisiana parishes along the Corridor, but also finds that pollution sources increase as the population of African Americans increases. MAP OF COMMUNITIES IN LOUISIANA Cancer Alley 1 Norco 3 1 4 2 Convent 2 3 Mossville 4 New Orleans East 2 INTRO HISTORY OF LOUISIANA’S MISSISSIPPI RIVER CHEMICAL CORRIDOR The air, soil, and water along the Mississippi River Chemical Corridor absorb more toxic substances annually than do most entire states. We look briefly at the history and development of this corridor, as well as the founding of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice (DSCEJ), to provide the background and context for the case studies that follow. -

Orleans Parish

PARISH FACT SHEET ORLEANS PARISH Orleans Parish is located south of Lake Pontchartrain and is the POPULATION POPULATION ECONOMIC smallest parish by land area in Louisiana, but one of the largest in CHANGE DRIVERS total population. The City of New Orleans and the parish of Orleans 389,617 operate as a unified city-parish government. New Orleans has one of TRANSPORTATION & the largest and busiest ports in the world and the greater New Orleans NAVIGATION area is a center of maritime industry and accounts for a significant -29% TOURISM BUSINESS portion of the nation’s oil refining and petrochemical production. New OIL & GAS Orleans also serves as a white-collar corporate base for onshore and offshore petroleum and natural gas production, in addition to being a Information from: 1) U.S. Census Quick Facts (2015 Estimate) 2) U.S. Census (2000-2010); city with several universities and other arts and cultural centers. and 3) City of New Orleans Economic Development. FUTURE WITHOUT ACTION LAND LOSS AND FLOOD RISK YEAR 50, MEDIUM ENVIRONMENTAL SCENARIO Flood depths from a 100-year storm event for initial conditions (year 0). Land change (loss or gain) for year 50 under the medium environmental scenario with no future protection or restoration actions taken. Orleans Parish faces significantly increased wetland loss over the next 50 years under the medium environmental scenario. With no further coastal protection or restoration actions, the parish could lose an additional 51 square miles, or 32% of the parish land primarily in the New Orleans East area. Additionally, with no further action, areas outside of the hurricane protection system face severe future storm surge based flood risk. -

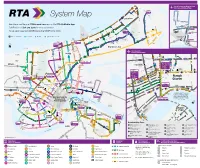

System Map 63 Paris Rd

Paris Rd. 60 Morrison Hayne 10 CurranShorewood Michoud T 64, 65 Vincent Expedition 63 Little Woods Paris Rd. Michoud Bullard North I - 10 Service Road Read 62 Alcee Fortier Morrison Lake Pontchartrain 17 Vanderkloot Walmart Paris Rd. T 62, 63, Lake Forest Crowder 64, 65 510 Dwyer Louis Armstrong New Orleans Lakefront Bundy Airport Read 63 94 60 International Airport Map Bullard Hayne Morrison US Naval 16 Joe Yenni 65 Joe Brown Reserve 60 Morrison Waterford Dwyer 64 Hayne 10 Training Center North I - 10 Service Road Park Michoud Old Gentilly Rd. Michoud Lakeshore Dr. Springlake CurranShorewood Bundy Pressburg W. Loyola W. University of SUNO New Orleans East Hospital 65 T New Orleans Downman 64, 65 T 57, 60, 80 62 H Michoud Vincent Loyola E. UNO Tilford Facility Expedition 80 T 51, 52, Leon C. Simon SUNO Lake Forest64 Blvd. Pratt Pontchartrain 55, 60 Franklin Park Debore Harbourview Press Dr. New Orleans East Williams West End Park Dwyer 63 Academy Robert E. Lee Pressburg Park s Paris St. Anthony System Map 63 Paris Rd. tis Pren 45 St. Anthony Odin Little Woods 60 10 H Congress Michoud Gentilly 52 Press Bullard W. Esplanade Bucktown Chef Menteur Hwy. Fillmore Desire 90 57 65 Canal Blvd. Mirabeau 55 32nd 51 Old Gentilly Bonnabel 15 See Interactive Maps at RTAforward.com and on the RTA GoMobile App. Duncan Place City Park y. Chef Menteur / Desire North I - 10 Service Road 5 Hw 62 Pontchartrain Blvd. Harrison Gentilly 94 ur Read 31st To Airport Chef Mente T 62, 63, 64, 65, 80, 94 Alcee Fortier 201 Clemson 10 Gentilly To Downtown MetairieMetairie Terrace Elysian Fields Fleur de Lis Lakeview St.