Properties of Minerals I. Crystal Habits II. Cleavage and Fracture in Minerals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz

Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz September 10 – 13, 2005 Golden, Colorado Sponsored by Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter; Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum; and U.S. Geological Survey 2 Cover Photos {top left} Fortification agate, Hinsdale County, Colorado, collection of the Geology Museum, Colorado School of Mines. Coloration of alternating concentric bands is due to infiltration of Fe with groundwater into the porous chalcedony layers, leaving the impermeable chalcedony bands uncolored (white): ground water was introduced via the symmetric fractures, evidenced by darker brown hues along the orthogonal lines. Specimen about 4 inches across; photo Dan Kile. {lower left} Photomicrograph showing, in crossed-polarized light, a rhyolite thunder egg shell (lower left) a fibrous phase of silica, opal-CTLS (appearing as a layer of tan fibers bordering the rhyolite cavity wall), and spherulitic and radiating fibrous forms of chalcedony. Field of view approximately 4.8 mm high; photo Dan Kile. {center right} Photomicrograph of the same field of view, but with a 1 λ (first-order red) waveplate inserted to illustrate the length-fast nature of the chalcedony (yellow-orange) and the length-slow character of the opal CTLS (blue). Field of view about 4.8 mm high; photo Dan Kile. Copyright of articles and photographs is retained by authors and Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter; reproduction by electronic or other means without permission is prohibited 3 Symposium on Agate and Cryptocrystalline Quartz Program and Abstracts September 10 – 13, 2005 Editors Daniel Kile Thomas Michalski Peter Modreski Held at Green Center, Colorado School of Mines Golden, Colorado Sponsored by Friends of Mineralogy, Colorado Chapter Colorado School of Mines Geology Museum U.S. -

Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana

Report of Investigation 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg 2015 Cover photo by Richard Berg. Sapphires (very pale green and colorless) concentrated by panning. The small red grains are garnets, commonly found with sapphires in western Montana, and the black sand is mainly magnetite. Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences in Montana Richard B. Berg Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology MBMG Report of Investigation 23 2015 i Compilation of Reported Sapphire Occurrences, RI 23 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 Descriptions of Occurrences ..................................................................................................7 Selected Bibliography of Articles on Montana Sapphires ................................................... 75 General Montana ............................................................................................................75 Yogo ................................................................................................................................ 75 Southwestern Montana Alluvial Deposits........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Rock Creek sapphire district ........................................................................ 76 Specifi cally Dry Cottonwood Creek deposit and the Butte area .................................... -

Microstructural, Mechanical, Corrosion and Cytotoxicity Characterization of Porous Ti-Si Alloys with Pore-Forming Agent

materials Article Microstructural, Mechanical, Corrosion and Cytotoxicity Characterization of Porous Ti-Si Alloys with Pore-Forming Agent Andrea Školáková 1,*, Jana Körberová 1 , Jaroslav Málek 2 , Dana Rohanová 3, Eva Jablonská 4, Jan Pinc 1, Pavel Salvetr 1 , Eva Gregorová 3 and Pavel Novák 1 1 Department of Metals and Corrosion Engineering, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (P.N.) 2 UJP Praha a.s., Nad Kamínkou 1345, 156 10 Prague 16, Czech Republic; [email protected] 3 Department of Glass and Ceramics, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] (D.R.); [email protected] (E.G.) 4 Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, Technická 5, 166 28 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-220-444-055 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 7 December 2020; Published: 9 December 2020 Abstract: Titanium and its alloys belong to the group of materials used in implantology due to their biocompatibility, outstanding corrosion resistance and good mechanical properties. However, the value of Young’s modulus is too high in comparison with the human bone, which could result in the failure of implants. This problem can be overcome by creating pores in the materials, which, moreover, improves the osseointegration. Therefore, TiSi2 and TiSi2 with 20 wt.% of the pore-forming agent (PA) were prepared by reactive sintering and compared with pure titanium and titanium with the addition of various PA content in this study. -

On Palaeozoic–Mesozoic Brittle Normal Faults Along the SW Barents Sea Margin: Fault Processes and Implications for Basement Permeability and Margin Evolution

research-articleResearch ArticleXXX10.1144/jgs2014-018K. Indrevær et al.Brittle Faults on the SW Barents Sea Margin 2014 Downloaded from http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on October 9, 2021 Journal of the Geological Society, London. http://dx.doi.org/10.1144/jgs2014-018 Published Online First © 2014 The Authors On Palaeozoic–Mesozoic brittle normal faults along the SW Barents Sea margin: fault processes and implications for basement permeability and margin evolution KJETIL INDREVÆR1,2*, HOLGER STUNITZ1 & STEFFEN G. BERGH1 1Department of Geology, University of Tromsø, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway 2DONG E&P Norge AS, Roald Amundsens Plass 1, N-9257 Tromsø, Norway *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Palaeozoic–Mesozoic brittle normal faults onshore along the SW Barents Sea passive margin off northern Norway give valuable insight into fault and fluid flow processes from the lower brittle crust. Micro- structural evidence suggests that Late Permian–Early Triassic faulting took place during multiple phases, with initial fault movement at minimum P–T conditions of c. 300 °C and c. 240 MPa (c. 10 km depth), followed by later fault movement at minimum P–T conditions of c. 275 °C and c. 220 MPa (c. 8.5 km depth). The study shows that pore pressures locally reached lithostatic levels (240 MPa) during faulting and that faulting came to a halt during early (deep) stages of rifting along the margin. Fault permeability has been controlled by heal- ing and precipitation processes through time, which have sealed off the core zone and eventually the damage zones after faulting. A minimum average exhumation rate of c. -

Experimental and Computational Study of Fracturing in an Anisotropic Brittle Solid

Mechanics of Materials 28Ž. 1998 247±262 Experimental and computational study of fracturing in an anisotropic brittle solid Abbas Azhdari 1, Sia Nemat-Nasser ) Center of Excellence for AdÕanced Materials, Department of Applied Mechanics and Engineering Sciences, UniÕersity of California-San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0416, USA Received 21 November 1996; revised 26 August 1997 Abstract For isotropic materials, stress- and energy-based fracture criteria lead to fairly similar results. Theoretical studies show that the crack-path predictions made by these criteria are not identical in the presence of strong material anisotropy. Therefore, experiments are performed to ascertain which criterion may apply to anisotropic materials. Notched specimens made from sapphire, a microscopically homogeneous and brittle solid, are used for the experiments. An attempt is made to locate the notch on different crystallographic planes and thus to examine the fracture path along different cleavage planes. The experimental observations are compared with the numerical results of the maximum tensile stress and the maximum energy-release rate criteria. It is observed that most of the notched specimens are fractured where the tensile stress is maximum, whereas the energy criterion fails to predict the fracture path of most of the specimens. For the tensile-stress Žn. s p s r g s fracture criterion, a dimensionless parameter, A ''2 R0 nn a Enn, is introduced, where nnand E nn, respectively, are the tensile stress and Young's modulus in the direction normal to the cleavage plane specified by the angle a Žthe fracture surface energy of this plane is ga . and R0 is a characteristic length, e.g. -

Activity 21: Cleavage and Fracture Maine Geological Survey

Activity 21: Cleavage and Fracture Maine Geological Survey Objectives: Students will recognize the difference between cleavage and fracture; they will become familiar with planes of cleavage, and will use a mineral's "habit of breaking" as an aid to identifying common minerals. Time: This activity is intended to take one-half (1/2) period to discuss cleavage planes and types and one (1) class period to do the activity. Background: Cleavage is the property of a mineral that allows it to break smoothly along specific internal planes (called cleavage planes) when the mineral is struck sharply with a hammer. Fracture is the property of a mineral breaking in a more or less random pattern with no smooth planar surfaces. Since nearly all minerals have an orderly atomic structure, individual mineral grains have internal axes of length, width, and depth, related to the consistent arrangement of the atoms. These axes are reflected in the crystalline pattern in which the mineral grows and are present in the mineral regardless of whether or not the sample shows external crystal faces. The axes' arrangement, size, and the angles at which these axes intersect, all help determine, along with the strength of the molecular bonding in the given mineral, the degree of cleavage the mineral will exhibit. Many minerals, when struck sharply with a hammer, will break smoothly along one or more of these planes. The degree of smoothness of the broken surface and the number of planes along which the mineral breaks are used to describe the cleavage. The possibilities include the following. Number of Planes Degree of Smoothness One Two Three Perfect Good Poor Thus a mineral's cleavage may be described as perfect three plane cleavage, in which case the mineral breaks with almost mirror-like surfaces along the three dimensional axes; the mineral calcite exhibits such cleavage. -

Correlation of the Mohs's Scale of Hardness with the Vickers' S Hardness Numbers

718 Correlation of the Mohs's scale of hardness with the Vickers' s hardness numbers. By E. WILFRED TAYLOR, C.B.E., F.R.M.S., F. Inst. P. Messrs. Cooke, Troughton & Simms, Ltd., York. [Read June 23, 1949.] INERALOGISTS have long been accustomed to describe hard- M ness with the aid of a scale devised by Friedrich Mohs, who lived from 1773 to 1839. The test is qualitative, each mineral in the scale being capable of scratching those that precede it, but the ten minerals have held their ground as a useful representative series with which it is now interesting to compare another method of estimating hard- ness. In the metallurgical world hardness is now usually expressed by means of the Vickers's hardness numbers or their equivalent, and the figures are derived from the size of the impression made by a diamond indenter in the form of a four-sided pyramid with the opposite faces worked to an included angle of 136 ~ More recently micro-hardness testers have been devised to enable minute impressions to be formed under light loads on small individual crystals of a metallic alloy, 1 and it occurred to the author to obtain hardness figures for the various types of optical glass by means of a scratch test with such an instrument. The intention was to draw a lightly loaded diamond across a polished glass surface and to measure the width of the resulting furrow. This method proved to be promising, but as an experiment a static indenter was also used, and it was dis- covered that glass was sufficiently plastic to take good impressions, so long as the load did not exceed 50 grams or thereabouts. -

Non-Stoichiometric Magnesium Aluminate Spinel

NON-STOICHIOMETRIC MAGNESIUM ALUMINATE SPINEL: MICROSTRUCTURE EVOLUTION AND ITS EFFECT ON PROPERTIES by J. Aaron Miller A thesis submitted to the Faculty and the Board of Trustees of the Colorado School of Mines in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Materials Science). Golden, Colorado Date _________________________ Signed: __________________________________ J. Aaron Miller Signed: __________________________________ Ivar E. Reimanis Thesis Advisor Golden, Colorado Date _________________________ Signed: _________________________ Dr. Angus Rockett Professor and Head Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering ii ABSTRACT Magnesium aluminate spinel is a material of interest for transparent armor applications. Owing to its unique combination of transparency to large portions of the electromagnetic spectrum and mechanical robustness, spinel is among the front runners for applications including transparent armor windows for military vehicles and space craft windows, missile radomes, and infrared windows. However, failure in such applications may lead to severe outcomes, creating motivation to further improve the mechanical reliability of the materials used. In this thesis, potential toughening mechanisms that utilize unique control over the evolution of second phase particles are explored. Al-rich spinel (MgO•nAl2O3) with a composition of n = 2 is investigated. First, it is demonstrated that precipitation of second phase Al2O3 from single phase spinel can be achieved by modifying the densification -

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota

Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalj of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the , » Commission Geology and Beryl Deposits of the Peerless Pegmatite Pennington County South Dakota By DOUGLAS M. SHERllDAN, HAL G. STEPHENS, MORTIMER H. STAATZ and JAMES J. NORTON PEGMATITES AND OTHER PRECAMBRIAN ROCKS IN THE SOUTHERN BLACK HILLS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 297-A This report concerns work done partly on behalf of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission and is published with the permission of the Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1957 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.50 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract.__________________________________________ 1 Geology Continued Introduction _______________________________________ 1 Peerless pegmatite Continued Location_____________________________________ 1 Chemical composition......____________ 17 History and production________________________ 2 Origin________ ____________________ _. 18 Past and present investigations.__________________ 3 Mineral deposits_____________________________ 21 Acknowledgments__________________________ 4 Mica__ _________ _________________________ 21 Mine workings _____________________________________ -

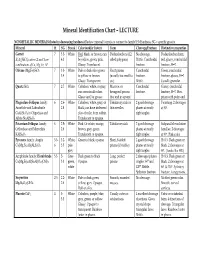

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE

Mineral Identification Chart – LECTURE NONMETALLIC MINERALS (listed in decreasing hardness) Review mineral formula to connect to family! H=Hardness; SG = specific gravity Mineral H SG Streak Color (and/or luster) Form Cleavage/Fracture Distinctive properties Garnet 7 3.5- White Red, black, or brown; can Dodecahedrons (12- No cleavage. Dodecahedron form, X3Y2(SiO4)3 where X and Y are 4.3 be yellow, green, pink. sided polygons) Brittle. Conchoidal red, glassy, conchoidal combinations of Ca, Mg, Fe, Al Glassy. Translucent. fracture. fracture, H=7. Olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 7 3.3- White Pale or dark olive green Short prisms Conchoidal Green, conchoidal 3.4 to yellow or brown. (usually too small to fracture. fracture, glassy, H=7. Glassy. Transparent. see). Brittle. Usually granular. Quartz SiO2 7 2.7 White Colorless, white, or gray; Massive; or Conchoidal Glassy, conchoidal can occur in all colors. hexagonal prisms fracture. fracture, H=7. Hex. Glassy and/or greasy. that end in a point. prism with point end. Plagioclase Feldspar family: 6 2.6- White Colorless, white, gray, or Tabular crystals or 2 good cleavage Twinning. 2 cleavages Anorthite and Labradorite 2.8 black; can have iridescent thin needles planes at nearly at 90°. CaAl2Si2O8 to Oligoclase and play of color from within. right angles. Albite NaAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. Potassium Feldspar family: 6 2.5- White Pink. Or white, orange, Tabular crystals 2 good cleavage Subparallel exsolution Orthoclase and Microcline 2.6 brown, gray, green. planes at nearly lamellae. 2 cleavages KAlSi3O8 Translucent to opaque. right angles. at 90°. Pink color. Pyroxene family: Augite 5.5- 3.2- White, Green to black; opaque. -

Methods Used to Identifying Minerals

METHODS USED TO IDENTIFYING MINERALS More than 4,000 minerals are known to man, and they are identified by their physical and chemical properties. The physical properties of minerals are determined by the atomic structure and crystal chemistry of the minerals. The most common physical properties are crystal form, color, hardness, cleavage, and specific gravity. CRYSTALS One of the best ways to identify a mineral is by examining its crystal form (external shape). A crystal is defined as a homogenous solid possessing a three-dimensional internal order defined by the lattice structure. Crystals developed under favorable conditions often exhibit characteristic geometric forms (which are outward expressions of the internal arrangements of atoms), crystal class, and cleavage. Large, well- developed crystals are not common because of unfavorable growth conditions, but small crystals recognizable with a hand lens or microscope are common. Minerals that show no external crystal form but possess an internal crystalline structure are said to be massive. A few minerals, such as limonite and opal, have no orderly arrangement of atoms and are said to be amorphous. Crystals are divided into six major classes based on their geometric form: isometric, tetragonal, hexagonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic. The hexagonal system also has a rhombohedral subdivision, which applies mainly to carbonates. CLEAVAGE AND FRACTURE After minerals are formed, they have a tendency to split or break along definite planes of weakness. This property is called cleavage. These planes of weakness are closely related to the internal structure of the mineral, and are usually, but not always, parallel to crystal faces or possible crystal faces. -

Characters Depending Upon Cohesion and Elasticity of Minerals

186 PHYSICAL MINERALOGY Thus, although it will be shown that the optical characters of crystals are in agreement in general with the symmetry of their form, they do not show all the variations in this symmetry. It is true, for example, that all directions are optically similar in a crystal belonging to any class under the isometric system; but this is obviously not true of its molecular cohesion, as may be shown by the cleavage. Again, all directions in a tetragonal crystal at right angles to the vertical axis are optically similar; but this again is not true of the cohesion. These points are further elucidated under the description of the special characters of each group. I. CHARACTERS DEPENDING UPON COHESION AND ELASTICITY 276. Cohesion, Elasticity. - The name cohesion is given to the force of attraction existing between the molecules of one and the.same body, in con- sequence of which they offer resistance to any influence tending to separate them, as in the breaking of a solid body or the scratching of its surface. Elasticity is the force which tends to restore the molecules of a body back into their original position, from which they have been disturbed, as when a body has suffered change of shape or of volume under pressure. The varying degrees of cohesion and elasticity for crystals of different minerals, or for different directions in the same crystal, are shown in the prominent characters: cleavage, fracture, tenacity, hardness; also in the gliding-planes, percussion-figures or pressure-figures, and the etching-figures. 277. Cleavage. - Cleavage is the tendency of a crystallized mineral to break in certain definite directions, yielding more or less smooth surfaces.