No Easy Walk to Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document. -

Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. the Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Apartheid Revolutionary Poem-Songs. The Cases of Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli Relatore Ch. Prof. Marco Fazzini Correlatore Ch. Prof. Alessandro Scarsella Laureanda Irene Pozzobon Matricola 828267 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 ABSTRACT When a system of segregation tries to oppress individuals and peoples, struggle becomes an important part in order to have social and civil rights back. Revolutionary poem-songs are to be considered as part of that struggle. This dissertation aims at offering an overview on how South African poet-songwriters, in particular the white Roger Lucey and the black Mzwakhe Mbuli, composed poem-songs to fight against apartheid. A secondary purpose of this study is to show how, despite the different ethnicities of these poet-songwriters, similar themes are to be found in their literary works. In order to investigate this topic deeply, an interview with Roger Lucey was recorded and transcribed in September 2014. This work will first take into consideration poem-songs as part of a broader topic called ‘oral literature’. Secondly, it will focus on what revolutionary poem-songs are and it will report examples of poem-songs from the South African apartheid regime (1950s to 1990s). Its third part will explore both the personal and musical background of the two songwriters. Part four, then, will thematically analyse Roger Lucey and Mzwakhe Mbuli’s lyrics composed in that particular moment of history. Finally, an epilogue will show how the two songwriters’ perspectives have evolved in the post-apartheid era. -

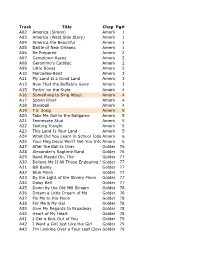

RUS Teaching Disk Track List.Pdf

Track # Title Chap Pg# A02 America (Simon) America 1 A03 America (West Side Story) America 1 A04 America the Beautiful America 1 A05 Battle of New Orleans America 1 A06 Be Prepared America 2 A07 Camptown Races America 2 A08 Geronimo's Cadillac America 2 A09 Little Boxes America 2 A10 Mercedes-Benz America 3 A11 My Land Is a Good Land America 3 A13A12 NowThe NightThat theThey Buffalo's Drove Old Gone Dixie DownAmerica 3 A15A14 Puttin'The Power on the & the Style Glory America 43 A16 Something to Sing About America 4 A17 Spoon River America 4 A18 Stewball America 4 A19 T. V. S o n g America 5 A20 Take Me Out to the Ballgame America 5 A21 Tennessee Stud America 5 A22 Tenting Tonight America 5 A23 This Land Is Your Land America 5 A24 What Did You Learn in School Today?America 6 A25 Your Flag Decal Won't Get You Into AmericaHeaven Anymore6 A27 After the Ball Is Over Golden 76 A28 Alexander's Ragtime Band Golden 76 A29 Band Played On, The Golden 77 A30 Believe Me If All Those Endearing YoungGolden Charms77 A31 Bill Bailey Golden 77 A32 Blue Moon Golden 77 A33 By the Light of the Silvery Moon Golden 77 A34 Daisy Bell Golden 77 A35 Down by the Old Mill Stream Golden 78 A36 Dream a Little Dream of Me Golden 78 A37 Fly Me to the Moon Golden 78 A38 For Me & My Gal Golden 78 A39 Give My Regards to Broadway Golden 78 A40 Heart of My Heart Golden 78 A41 I Get a Kick Out of You Golden 79 A42 I Want a Girl Just Like the Girl Golden 79 A43 I'm Looking Over a Four Leaf CloverGolden 79 A44 I'm Sitting on Top of the World Golden 79 A45 In a Little Spanish -

Hanukkah Candle Lighting Song Book

Beth Israel’s Zoom Hanukkah Candle Ligh8ng with Cantor Michael Zoosman and Monika Schwartzman כ״ו ְּבִכְסֵלו תשפ״א/December 12, 2020/27 Kislev 5781 HINEI EL Y’SHU’ATI ִה ֵּנה ֵאל ְיׁשָוּﬠִתי, ֶאְבַטח ְולֹא ֶאְפָחד, ִכי ָﬠִזּי ְוִזְמָרת ָיּה ה׳, ,Hineih eil y'shua-, evtach v'lo efchad ַו ְי ִהי ִלי ִל ׁיש ָוּﬠה: ׁ ְוּש ַא ְב ֶּתם ַמ ִים ְּב ָׂש ׂשוֹן ִמ ַּמ ַﬠְיֵני ַה ְי ׁש ָוּﬠה: :ki ozi v'zimrat yah Adonai, vay'hi li lishuah Ush'avtem mayim b'sason mima-aynei hayshuah: ַלה׳ ַהְיׁשָוּﬠה ַﬠל ַﬠ ְּמָך ִבְרָכֶתָך ֶּסָלה: ה׳ ְצָבאוֹת ִﬠ ָּמנוּ :L’Adonai hayshuah al am'cha virchatecha selah ִמ ְׂש ָּגב ָלנוּ ֱאלֹקי ַי ֲﬠקֹב ֶס ָלה: ה׳ ְצ ָבאוֹת ַא ְשֵרי ָאָדם ּב ֵֹטח :Adonai tz'va-ot imanu misgav lanu elohei ya-akov selah ָּבְך: ה׳ ה ִׁוֹשיָﬠה ַה ֶּמֶלְך ַיֲﬠֵננוּ ְביוֹם ָקְרֵאנוּ: :Adonai tz'va-ot ashrei adam botei-ach bach Adonai hoshi-ah hamelech ya-aneinu v'yom kor'einu: ַלְיִּהוּדים ָהְיָתה אוָֹרה ְו ִׂשְמָחה ְו ָׂשׂשוֹן ִויָקר: :Ly'hudim hay'tah orah v'simchah v'sason vikar ֵּכן ִּת ְה ֶיה ָּלנוּ, ּכוֹס ְי ׁשוּעוֹת ֶאָּׂשא. ְוּב ֵׁשם ה׳ ֶאְקָרא: :Kein -hyeh lanu. Kos y'shuot esa. Uv'sheim Adonai ekra 1. Birkhot Havdalah and Hanukkah Melody by Debbie Friedman ָּב ְרוּך ַא ָּתה ה׳, ֱאלֹקינוּ ֶמ ֶל ְך ָהעוֹ ָלם, Yai lai lai lai lai lai lai lai, Lai lai lai lai lai lai lai lai Yai lai lai lai lai lai lai lai lai Lai lai lai lai lai (repeat) ּבוֵֹרא ְפִרי ַה ָג ֶפן. -

“Our Silence Buys the Battles”: the Role of Protest Music in the U.S.-Central American Peace and Solidarity Movement

“Our Silence Buys the Battles”: The Role of Protest Music in the U.S.-Central American Peace and Solidarity Movement CARA E. PALMER “No más! No more!” “No más! No more!” Shout the hills of Salvador Shout the hills of Salvador Echo the mountains of Virginia In Guatemala, Nicaragua We cry out “No más! No more!” We cry out “No más! No more!”1 In the 1980s, folk singer John McCutcheon implored his fellow U.S. citizens to stand in solidarity with Central Americans in countries facing United States (U.S.) intervention. Combining both English and Spanish words, his song “No Más!” exemplifies the emphasis on solidarity that characterized the dozens of protest songs created in connection with the U.S.-Central American Peace and Solidarity Movement (CAPSM).2 McCutcheon’s song declared to listeners that without their active opposition, the U.S. government would continue to sponsor violence for profit. McCutcheon sang, “Our silence buys the battles, let us cry, ‘No más! No more!,’” urging listeners to voice their disapproval of the Reagan administration’s foreign policies, because remaining silent would result in dire consequences. One hundred thousand U.S. citizens mobilized in the 1980s to protest U.S. foreign policy toward Central America. They pressured Congress to end U.S. military and financial aid for the military junta in El Salvador, the military dictatorship in Guatemala, and the Contras in Nicaragua. The Reagan administration supported armed government forces in El Salvador and Guatemala in their repression of the armed leftist groups FMLN and MR-13, and the Contras in Nicaragua in their war against the successful leftist revolution led by the FSLN. -

Gold Castle Label Discography the Label Was Founded in 1986 by Danny Goldberg and Juilan Schlossberg

Gold Castle Label Discography The label was founded in 1986 by Danny Goldberg and Juilan Schlossberg. Originally distributed by PolyGram, it switched its distribution to CEMA (Capitol) in 1989. 171 Series (Distributed by PolyGram): 171 001-1 –No Easy Walk to Freedom –Peter, Paul & Mary [1986] Weave Me the Sunshine/Right Field/I’d Rather Be in Love/State of the Heart/No Easy Walk to Freedom//Greenland Whale Fisheries/Whispered Words/El Salvador/Greenwood/Light One Candle 171 002-1 –Trust Your Heart –Judy Collins [1987] Trust Your Heart/Amazing Grace/Jerusalem/Day by Day/The Life You Dream//The Rose/Moonfall/Morning Has Broken/When a Child Is Born/When You Wish Upon a Star 171 003-1 –The Washington Squares –Washington Squares [1987] 171 004-1 –Recently –Joan Baex [1987] 171 005-1 –Waiting for a Miracle: Singles 1970-1987 –Bruce Cockburn [1987] 2-LP set. 171 006-1 –Intervals in Sunlight –John Weider [1987] 171 007-1 –Pilgrims –Eliza Gilkyson [1987] 171 008-1 –The Trouble with Normal –Bruce Cockburn [1987] Reissue of Gold Mountain GM-3283. 171 009-1 –Dancing in the Dragon’sJaws –Bruce Cockburn [1987] Reissue of Gold Mountain GM-3276. 171 010-1 –Stealing Fire –Bruce Cockburn [1987] Reissue of Gold Mountain GM-80012. Lovers in a Dangerous Time/Maybe the Poet/Sahara Gold/Making Contact/Peggy’sKitchen Wall//To Raise the Morning Star/Nicaragua/If I Had a Rocket Launcher/Dust and Diesel. 171 011-1 –Short Vacation –Kenny Vance [1987] 171 012-1 –Sunbathing in Leningrad –David Hayes [1988] Lindonvarne/Summer Storm/County Fair/October Wind/Elephant -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Classical by Composer

Classical by Composer Adolphe Adam, Giselle (The Complete Ballet), Bolshoi Theater Orchestra, Algis Zuraitis,ˆ MHS 824750F Isaac Albeniz, Iberia (complete), Maurice Ravel, Rapsodie Espagnole, Jean Morel, Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, RCA Living Stereo LSC-6094 (audiophile reissue) 2 records Tomaso Albinoni, Adagio for Strings and Organ, Concerto a Cinque in C Major, Concerto a Cinque in C Major Op. 5, No. 12, Concerto a Cinque in E Minor Op. 5, No. 9, The Sinfonia Instrumental Ensemble, Jean Witold, Nonesuch H-71005 Alfonso X, El Sabio, Las Cantigas de Santa Maria, History of Spanish Music, Volume I MHS OR 302 Charles Valentin Alkan, Piano Pieces Bernard Ringeissen Piano Harmonia Mundi B 927 Gregorio Allegri, Miserere, and other Great Choral Works CD ASV CD OS 6036 DDD, ADD 1989 Gregorio Allegri, Miserere, and other Choral Masterpieces CD Naxos 8.550827 DDD 1993 Gregorio Allegri, Miserere, Giovanni Pierluigi, Stabat Mater, Hodie Beata Virgo, Senex puerum portabat, Magnificat, Litaniae de Beata Virgine Maria, Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, Sir David Willcocks, CD London 421 147-2 ADD 1964 William Alwyn, Symphony 1, London Philharmonic Orchestra, William Alwyn, HNH 4040 Music of Leroy Anderson, Vol. 2 Frederick Fennell, Eastman-Rochester “POPS” Orchestra, 19 cm/sec quarter-track tape Mercury Living Presence ST-90043 The Music of Leroy Anderson, Frederick Fennell, Eastman-Rochester Pops Orchestra, Mercury Living Presence SR-90009 (audiophile) The Music of Leroy Anderson, Sandpaper Ballet, Forgotten Dreams, Serendata, The Penny Whistle Song, Sleigh Ride, Bugler’s Holiday, Frederick Fennell, Eastman-Rochester POPS Orchestra, 19 cm/sec half-track tape Mercury Living Presence (Seeing Ear) MVS5-30 1956 George Antheil, Symphony No. -

Anne Feeney) You Got to Laugh When the Spirit Says Laugh! Was It Cesar Chavez? Or Rosa Parks That Day? You Got to Laugh

HAVE YOU BEEN TO JAIL FOR JUSTICE? (Anne Feeney) You got to laugh when the spirit says laugh! Was it Cesar Chavez? Or Rosa Parks that day? You got to laugh . etc. Some say Dr. King or Gandhi that set them on their way Chorus No matter who your mentors are it's pretty plain to see That, if you've been to jail for justice, you're in good You got to dance . etc. company Chorus Chorus You got to sing . etc. Have you been to jail for justice? I want to shake your hand Chorus Cause sitting in and lyin' down are ways to take a stand Have you sung a song for freedom? or marched that picket You got to shout . etc. line? Chorus Have you been to jail for justice? Then you're a friend of mine You got to bid . etc. Chorus Chorus You law abiding citizens, come listen to this song You got to do when the spirit says do! Laws were made by people, and people can be wrong You got to do when the spirit says do! Once unions were against the law, but slavery was fine When the spirit says do, you’ve got to do, oh Lord! Women were denied the vote & children worked the mine The more you study history the less you can deny it You got to do when the spirit says do A rotten law stays on the books til folks like us defy it Chorus You got to do when the spirit says do Chorus WE SHALL NOT BE MOVED (originally by The Seekers The law's supposed to serve us, and so are the police – adapted by many) And when the system fails, it's up to us to speak our peace It takes eternal vigilance for justice to prevail So get courage from your convictions We shall not, we shall not be moved. -

CATHEDRAL | EPIPHANY 2014 Hope and Healing What Rhymes with “Gargoyles”? C______F______S______

CATHEDR AL AGE WASHINGTON NATIONAL CATHEDRAL | EPIPHANY 2014 hope and healing What rhymes with “gargoyles”? C________ F_______ S______ hint It also rhymes with “angels,” “music,” “programs,” “services,” and more . If you’re still stumped, we invite you to learn more about CFS: the Cathedral Founders Society! Members join by letting us know of their bequests or other planned gifts to the Cathedral. In return, members receive the benefit of knowing that they are helping to preserve this spiritual home for the nation, gargoyles and all, for centuries to come. No dues, obligations, or solicitations are involved in membership—but it does allow us to thank you, and it may inspire generosity in others. To learn more, email the Cathedral’s planned-giving office ([email protected]) or call (202) 537-5747. above “master carver” gargoyle, artist and carver john guarente photo r. llewellyn CATHEDR AL AGE EPIPHANY 2014 Contents 2 Comment 14 This Little Light 24 Focus A Virtual Angelus in Stone and Glass A Vigil for the Victims of Gun Violence News from the Cathedral the very rev. gary hall m. leigh harrison Bishop’s Garden rededication, carillon anniversary, canon installation, staff 4 Like an African Early 16 Sounding the Severies announcements, vandalism, and Setting the Standard for Restoring Children’s Sabbath Morning Sun and Preserving this Spiritual Home Celebrating the Life and Legacy 28 From the Pulpit for the Nation of Nelson Mandela Reasons for Lament craig w. stapert margaret shannon the rev. canon gina gilland campbell 8 Proclaiming Peace 20 A Prayer for When The Final Barrier the very rev. -

Interview with Peter, Paul & Mary

Peter, Paul ary HarmonyM from an Era of Protest BY ROGER DEITZ (Photos by Robert Corwin unless otherwise noted.) received an invitation to Peter Yarrows charm- many great songs. Their PBS special, Lifelines, had recently ing Manhattan apartment ... those modest digs aired, the latest in a series of the trios notable projects. It fea- known around town by admiring folkies as The tured three generations of folk artists singing side by side in House that Puff Built. This was a couple of years timeless kinship. This small gathering of press at Yarrows ago, after I had written a Billboard article about &was clearly, I surmised, an opportunity for Warner Bros. to Ferron, another Warner artist, so I just assumed this get-to- keep the buzz going, give the project legs. Thats show biz getherI with Peter, Paul and Mary was an additional press op publicity-speak. PP&Ms folk music message may be univer- request. Eagerly, I looked forward to meeting these three icons sal, heartfelt, meaningful and honest ... but keep in mind that of popular culture that championed so many causes with so the trio is a successful business after all. I dont often find myself using the words folk and successful business in the same sentence, but here I do so with a smile ... and with pride. For some reason, this union of Peter Yarrow, Noel Paul Stookey and Mary Travers had slipped the surly bonds of folk to launch an astonishing number of important folk songs into the mainstream subconscious and onto the Billboard charts. Yet the three were anything but exploitative, pop-for-pops- sake, flavor-of-the-week artists. -

Celebrating the Life, Legacy, and Values of Nelson Mandela • Wednesday, December 11, 2013 Prelude Steal Away Arr

celebrating the life, legacy, and values of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela july 18, 1918–december 5, 2013 wednesday, december 11, 2013 11 am washington national cathedral During my lifetime, I have dedicated myself to the struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if it needs to be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die. nelson mandela Celebrating the Life, Legacy, and Values of Nelson Mandela • Wednesday, December 11, 2013 prelude Steal Away arr. Bob Chilcott Agnus Dei arr. Samuel Barber If I can help somebody Nathan Carter performed by the Morgan State University Choir Just a closer walk with thee traditional That we might walk free Antonio García Sobukwe Ezra Ngcukana performed by the Virginia Commonwealth University Alumni Jazz Quartet It is well with my soul traditional We shall overcome traditional performed by Tahrir Thandeka Rasool (piano) and Roger Isaacs (solo) God is James Cleveland Even me Patrick Lundy Safe in his arms Milton Brunson performed by the WPAS Children of the Gospel Choir Blowin’ in the Wind Bob Dylan performed by Peter Yarrow Bawo, Thixo Somandla traditional Zulu prayer (Prayer for Mandela) traditional performed by the Pacific Boychoir Chinese proverb S. Durant, Arr. by Ysaye M. Barnwell Saboya traditional, Arr. Nitanju Bolade Casel Civil Rights Medley performed by Sweet Honey in the Rock Please stand.