Effect of Artificial Barriers on the Distribution of the Invasive Signal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Home Range of Signal Crayfish in a British Lowland River

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquatic Commons HOME RANGE OF SIGNAL CRAYFISH 45 THE HOME RANGE OF SIGNAL CRAYFISH IN A BRITISH LOWLAND RIVER RUI-ZHANG GUAN AND PETER WILES (Dr R.-Z. Guan, Xiamen Fisheries College, Jimei University, Xiamen, Fuijan 361021, P.R. China and P. R. Wiles, The Clore Laboratory for Life Sciences, The University of Buckingham, Bucks MK18 1EG, England.) Introduction The signal crayfish Pacifastacus leniusculus (Dana), a native of north-western North America, is now a common resident in some British fresh waters following its introduction to England in 1976 (Lowery & Holdich 1988). In 1984, signal crayfish were introduced into the River Great Ouse, the major lowland river in southern central England, where they have established a large breeding population, with a mean density of 15 per m2 in riffles during summer and 2 per m2 in pools. By the summer of 1994, they had occupied an 11.4 km section of river (Guan 1995). The unexpected burrowing behaviour of signal crayfish in the river was reported by Guan (1994). Signal crayfish not only take natural shelters but they also dig extensive burrows in the mud banks of the river. They are typically nocturnal. In this study we have investigated crayfish movements and addressed two questions: (1), how large is the home range? [Burt's (1943) definition of home range was adopted here, i.e., "The area traversed by the individual in its normal activities of food gathering, mating, and caring for young"]; and (2), does the home range vary between sexes and crayfish of different sizes? Study sites Two sites near Thornborough Weir (map reference: OS 738355) were chosen for study. -

Pacifastacus Leniusculus) out Consume Newly Introduced Crayfishes for Invasive Chinese Mystery Snail (Bellamya Chinensis)

Aquat Ecol (2009) 43:1073–1084 DOI 10.1007/s10452-009-9244-9 Home-field advantage: native signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus) out consume newly introduced crayfishes for invasive Chinese mystery snail (Bellamya chinensis) Julian D. Olden Æ Eric R. Larson Æ Meryl C. Mims Received: 5 November 2008 / Accepted: 3 April 2009 / Published online: 21 April 2009 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2009 Abstract The introduction of non-indigenous plants, the most profitable prey choice. By contrast, previous animals and pathogens is one of today’s most pressing studies have reported the opposite pattern for crayfish environmental challenges. Freshwater ecologists are consumption on thin-shelled snails. For all snail size challenged to predict the potential consequences of classes, we found that native P. leniusculus and species invasions because many ecosystems increas- invasive O. virilis consumed greater numbers of snails ingly support novel assemblages of native and non- than invasive P. clarkii. Moreover, P. leniusculus native species that are likely to interact in complex consistently handled and consumed snails at a faster ways. In this study we evaluated how native signal pace compared to both invasive crayfishes across the crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus) and non-native red range of snail sizes examined in our study. These swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) and northern results suggest not only that B. chinensis is a suitable crayfish (Orconectes virilis) utilize a novel prey food source for crayfish, but also that native resource: the non-native Chinese mystery snail (Bell- P. leniusculus may ultimately out-consume invasive amya chinensis). All species are widespread in the crayfishes for this new prey resource. -

10-18 Establishment and Care of a Colony of Parthenogenetic Marbled

(Online) ISSN2042-633X (Print) ISSN 2042-6321 Invertebrate Rearing 1(1):10-18 Establishment and care of a colony of parthenogenetic marbled crayfish, Marmorkrebs Stephanie A. Jimenez and Zen Faulkes Department of Biology, The University of Texas-Pan American Invertebrate Rearing is an online journal for all people interested in the rearing of invertebrates in captivity, whether for research or for pleasure. It is the belief of the editor that greater communication between professional researchers, amateur scientists and hobbyists has great benefits for all concerned. In order to cater for such a diverse audience the journal publishes short and popular articles and reviews as well as scientific articles. Where possible scientific articles are peer reviewed. Submissions to the journal can be made via the website (http://inverts.info) where you may also sign up for e-mail notification of new issues. Invertebrate Rearing Establishment and care of a colony of parthenogenetic marbled crayfish, Marmorkrebs Article (Peer-reviewed) Stephanie A. Jimenez and Zen Faulkes Department of Biology, The University of Texas-Pan American, 1201 W. University Drive, Edinburg, TX 78539, USA. Email: [email protected] Abstract Marmorkrebs are parthenogenetic marbled crayfish whose origins are unknown. They have potential to be a model organism for biological research because they are genetically uniform, and to be an invasive pest species. Maintaining self-sustaining breeding colonies is a key element of most successful model organisms. We tried to find the best conditions for establishing and maintaining a Marmorkrebs breeding colony for research. Marmorkrebs can be bred in a compact tank system originally designed for zebrafish. -

How the Red Swamp Crayfish Took Over the World Running Title Invasion

1 Title 2 One century away from home: how the red swamp crayfish took over the world 3 Running Title 4 Invasion history of Procambarus clarkii 5 Authors 6 Francisco J. Oficialdegui1*, Marta I. Sánchez1,2,3, Miguel Clavero1 7 8 Affiliations 9 1. Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC). Avenida Américo Vespucio 26, 10 Isla de la Cartuja. 41092. Seville, Spain 11 2. Instituto Universitario de Investigación Marina (INMAR) Campus de Excelencia 12 Internacional/Global del Mar (CEI·MAR) Universidad de Cádiz. Puerto Real, 13 Cadiz (Spain). 14 3. Present address: Departamento de Biología Vegetal y Ecología, Facultad de 15 Biología, Universidad de Sevilla, Apartado 1095, 41080, Seville, Spain 16 17 Contact: [email protected] Francisco J. Oficialdegui. Department of Wetland 18 Ecology. Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC). C/Américo Vespucio 26. Isla de 19 la Cartuja. 41092. Seville (Spain). Phone: 954466700. ORCID: 0000-0001-6223-736X 20 21 Marta I. Sánchez. [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-8349-5410 22 Miguel Clavero. [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-5186-0153 23 24 Keywords: Alien species; GBIF; Global translocations; Historical distributions; 25 iNaturalist; Invasive species; Pathways of introduction; Procambarus clarkii; 26 1 27 ABSTRACT 28 The red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) (hereafter RSC), native to the southern 29 United States and north-eastern Mexico, is currently the most widely distributed 30 crayfish globally as well as one of the invasive species with most devastating impacts 31 on freshwater ecosystems. Reconstructing the introduction routes of invasive species 32 and identifying the motivations that have led to those movements, is necessary to 33 accurately reduce the likelihood of further introductions. -

Signal Crayfish

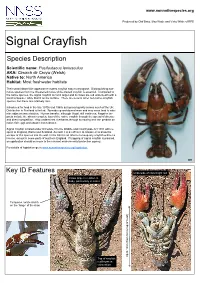

www.nonnativespecies.org Produced by Olaf Booy, Max Wade and Vicky White of RPS Signal Crayfish Species Description Scientific name: Pacifastacus leniusculus AKA: Cimwch dir Croyw (Welsh) Native to: North America Habitat: Most freshwater habitats Their small lobster-like appearance makes crayfish easy to recognise. Distinguishing non- native species from the threatened native white-clawed crayfish is essential. Compared to the native species, the signal crayfish is much larger and its claws are red underneath with a small turquoise / white blotch on the surface. There are several other non-native crayfish species, but these are relatively rare. Introduced for food in the late 1970s and 1980s but spread quickly across much of the UK. Distribution in Scotland is limited. Spreads up and downstream and may cross land to colo- nise adjacent water bodies. Human transfer, although illegal, still continues. Negative im- pacts include the almost complete loss of the native crayfish through the spread of disease and direct competition. Also undermines riverbanks through burrowing and can predate on native fish eggs and aquatic invertebrates. Signal crayfish is listed under Schedule 9 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 with re- spect to England, Wales and Scotland. As such it is an offence to release or to allow the escape of this species into the wild. In the UK it is an offence to keep any crayfish without a license, except in some parts of southern England. If trapping of signal crayfish is planned, an application should be made to the relevant environmental protection agency. For details of legislation go to www.nonnativespecies.org/legislation. -

Signal Crayfish

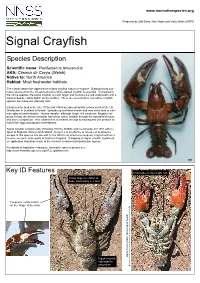

www.nonnativespecies.org Produced by Olaf Booy, Max Wade and Vicky White of RPS Signal Crayfish Species Description Scientific name: Pacifastacus leniusculus AKA: Cimwch dir Croyw (Welsh) Native to: North America Habitat: Most freshwater habitats Their small lobster-like appearance makes crayfish easy to recognise. Distinguishing non- native species from the threatened native white-clawed crayfish is essential. Compared to the native species, the signal crayfish is much larger and its claws are red underneath with a small turquoise / white blotch on the surface. There are several other non-native crayfish species, but these are relatively rare. Introduced for food in the late 1970s and 1980s but spread quickly across much of the UK. Distribution in Scotland is limited. Spreads up and downstream and may cross land to colo- nise adjacent water bodies. Human transfer, although illegal, still continues. Negative im- pacts include the almost complete loss of the native crayfish through the spread of disease and direct competition. Also undermines riverbanks through burrowing and can predate on native fish eggs and aquatic invertebrates. Signal crayfish is listed under Schedule 9 to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 with re- spect to England, Wales and Scotland. As such it is an offence to release or to allow the escape of this species into the wild. In the UK it is an offence to keep any crayfish without a license, except in some parts of southern England. If trapping of signal crayfish is planned, an application should be made to the -

Redalyc.BALANCE ENERGÉTICO DEL ACOCIL Cambarellus

Universidad y Ciencia ISSN: 0186-2979 [email protected] Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco México Rodríguez Serna, Miguel; Carmona Osalde, Claudia BALANCE ENERGÉTICO DEL ACOCIL Cambarellus montezumae (Saussure) (CRUSTACEA:ASTACIDAE:CAMBARIDE) PÉRDIDA DE ENERGÍA EN LA TASA METABÓLICA Universidad y Ciencia, vol. 36, núm. 18, diciembre, 2002, pp. 128-134 Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco Villahermosa, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=15403604 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Universidad y Ciencia Volumen 18 Número 36 Diciembre 2002 BALANCE ENERGÉTICO DEL ACOCIL Cambarellus montezumae (Saussure) (CRUSTACEA:ASTACIDAE:CAMBARIDE) PÉRDIDA DE ENERGÍA EN LA TASA METABÓLICA ENERGETIC BALANCE OF CRAYFISH Cambarellus montezumae (Saussure) (CRUSTACEA:ASTACIDAE:CAMBARIDE): ENERGY LOSS IN THE METABOLIC RATE Miguel Rodríguez-Serna ([email protected] ) 1 Claudia Carmona-Osalde ([email protected]) 2 1Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología, Ecología y Recursos Naturales Laboratorio de Biología Marina Experimental. Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche, México. 2Centro de Investigación y de Estudios Avanzados del IPN Unidad Mérida (CINVESTAV-IPN) Departamento de Recursos del Mar, Laboratorio de Nutrición. Mérida, Yucatán, México Artículo recibido: 04 de junio de 2002 Artículo aceptado: 19 de noviembre de 2002 RESUMEN El objetivo de esta investigación fue determinar las pérdidas de energía por el metabolismo y su efecto en la nutrición de los acociles de la especie Cambarellus montezumae (Saussure). -

A Draft National Management Plan for the Genus Eriochheir

A Draft National Management Plan For the Genus Eriochheir Submitted to the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force Prepared by the Chinese mitten crab Control Committee February 2002 Executive Summary During the fall of 1998, the downstream migration of the introduced Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis, in the San Francisco Estuary reached tremendous proportions. In the short time since its introduction in the late 1980s or early 1990s, this crab has become very abundant and widely distributed throughout the watershed. The increase in population is similar to reports of the German experience with the mitten crab in the 1930s. The adult migration period of the mitten crab has seriously impacted the Central Valley water diversion fish salvage facilities and recreational fishing. In addition, commercial fisheries and other water diversion activities have been affected. Mitten crab burrows are also contributing to increased erosion and bank slumping. The large, omnivorous crab population may also threaten agricultural crops and ecosystem health. The literature and the experience in San Francisco Bay indicate that the genus Eriocheir poses a significant threat to the economic and environmental resources of several estuaries of North America and that, unless prompt measures are taken, Eriocheir species may establish populations in new areas of the country. The Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force (ANSTF) is an intergovernmental body established by the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act (NANPCA) of 1990. The ANSTF has followed the status of the mitten crab invasion of California since early 1998 and determined that, under the authority of NANPCA, the development of a cooperative and comprehensive management plan for the genus Eriocheir was appropriate and necessary. -

Assessment of the Risk to Norwegian Biodiversity from Import and Keeping of Crustaceans in Freshwater Aquaria

VKM Report 2021: 02 Assessment of the risk to Norwegian biodiversity from import and keeping of crustaceans in freshwater aquaria Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment VKM Report 2021: 02 Assessment of the risk to Norwegian biodiversity from import and keeping of crustaceans in freshwater aquaria. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment 15.02.2021 ISBN: 978-82-8259-356-4 ISSN: 2535-4019 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM) Postboks 222 Skøyen 0213 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] vkm.no vkm.no/english Cover photo: Mohammed Anwarul Kabir Choudhury/Mostphotos.com Suggested citation: VKM, Gaute Velle, Lennart Edsman, Charlotte Evangelista, Stein Ivar Johnsen, Martin Malmstrøm, Trude Vrålstad, Hugo de Boer, Katrine Eldegard, Kjetil Hindar, Lars Robert Hole, Johanna Järnegren, Kyrre Kausrud, Inger Måren, Erlend B. Nilsen, Eli Rueness, Eva B. Thorstad and Anders Nielsen (2021). Assessment of the risk to Norwegian biodiversity from import and keeping of crustaceans in freshwater aquaria. Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment. VKM report 2021:02, ISBN: 978-82-8259- 356-4, ISSN: 2535-4019. Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (VKM), Oslo, Norway. 2 Assessment of the risk to Norwegian biodiversity from import and keeping of crustaceans in freshwater aquaria Preparation of the opinion The Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food and Environment (Vitenskapskomiteen for mat og miljø, VKM) appointed a project group to draft the opinion. -

LOVE THEM Or HATE THEM?

INVASIVEINVASIVE DECAPODSDECAPODS LOVELOVE THEMTHEM oror HATEHATE THEM?THEM? DavidDavid HoldichHoldich TheThe intentionalintentional oror accidentalaccidental introductionintroduction ofof invasiveinvasive speciesspecies isis secondsecond onlyonly toto habitathabitat destructiondestruction inin causingcausing thethe globalglobal lossloss ofof biodiversity.biodiversity. AquaticAquatic systemssystems presentpresent fewfew barriersbarriers toto thethe spreadspread ofof invasiveinvasive speciesspecies onceonce theythey becomebecome establishedestablished (Cook(Cook && Clark,Clark, 2004).2004). However,However, littlelittle emphasisemphasis hashas beenbeen putput onon thethe considerableconsiderable impactimpact thatthat decapoddecapod crustaceanscrustaceans cancan havehave onon inlandinland waters.waters. Global Strategy on Invasive e.g.e.g. Global Strategy on Invasive AlienAlien Species.Species. McNeelyMcNeely etet alal.. (2001).(2001). IUCNIUCN Gland,Gland, Switzerland,Switzerland, andand Cambridge,Cambridge, UK,UK, inin collaborationcollaboration withwith thethe GlobalGlobal InvasiveInvasive SpeciesSpecies Programme.Programme. OneOne briefbrief mentionmention ofof invasiveinvasive decapods,decapods, i.e.i.e. crayfishcrayfish escapingescaping fromfrom aa LondonLondon fishfish market!market! ApproximatelyApproximately 10,00010,000 speciesspecies ofof decapoddecapod crustaceans,crustaceans, whichwhich includeinclude thethe prawns,prawns, shrimps,shrimps, lobsters,lobsters, crabscrabs andand crayfish.crayfish. ManyMany havehave aquaculturalaquacultural -

Growth and Macronutritional Requirements of Signal Crayfish, Pacifastacus Leniusculus (Dana) in Aquaculture

Growth and macronutritional requirements of signal crayfish, Pacifastacus leniusculus (Dana) in aquaculture Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Yarno Sebastian Wolf Kiel 2004 Referent/in: Prof. Dr. Harald Rosenthal Korreferent/in: Prof. Dr. Hansen Tag der mündlichen Prüfung:13. Juli 2004 Zum Druck genehmigt: Kiel, den 15. Juli 2004 Der Cancer ist mehr kalt als warm und hat mehr Wärme von der Erde als von der Luft. Er liebt den Tag und die Nacht, weil er vorwärts geht wie die Sonne und rückwärts wie der Mond. Er hat gesundes Fleisch, und der Gesunde kann ihn ebenso essen wie der Kranke, außer wessen Magen kalt und bestoppet ist. Wer Verdauungsschwierigkeiten hat, für den ist der Krebs eine zu kräftige Speise, weil er ihn schwer verdauen kann. Deshalb ist er für ihn als Speise ungeeignet. In seinem Kopfe aber findet sich ein Fett von frischer Kraft, das crebezes smer genannt wird. Nimm davon und füge eine gehörige Menge Butter dazu und knyt dies zusammen. Wer im Gesicht und um die Nasenlöcher quedelechte hat, so als wollten Schmerz und Geschwüre dort Pusteln bilden, der soll sich in der Nacht an den betreffenden Stellen oft damit einreiben. Wenn er dann morgens vom Bett aufsteht, soll er sich diese Salbe mit Wein aus seinem Gesicht waschen, und er wird eine schöne Gesichtshaut bekommen, so daß sich dort auch keine Pusteln mehr bilden. Hildegard von Bingen, Das Buch von den Fischen, um 1155 Ja, mach nur einen Plan Sei nur ein großes Licht! Und mach dann noch 'nen zweiten Plan Geh' n tun sie beide nicht. -

Zoology- the Crustaceans in Response to Convid 19 April

ZOOLOGY- THE CRUSTACEANS IN RESPONSE TO CONVID 19 APRIL 2, 2020 nd Dear students and parents, April 2 , 2020 Beginning two days prior to our last day at school I issued work packets to all students in all classed; the content of which was spanning a two-three week period. Now that our removal from school will continue to at least May 1st, I have provided the following work packets which will span the remainder of the year, should our crisis continue. The following folders are available: ANATOMY – PHYSIOLOGY 1. Packet – THE HUMAN REPRODUCATIVE AND ENDOCRINE SYSTEMS. 2. Packet- THE HUMAN NERVOUS SYSTEM 3. Packet handed our prior to our last day: THE HUMAN EXCRETORY SYSTEM ZOOLOGY 1. Packet- STUDY OF THE CRUSTACEANS 2. Packet- STUDY OF THE INSECTS 3. Packet- handed our prior to our last day- INTRODUCTION TO THE ARTRHROPODS- CLASSES MYRIAPODA AND ARACHNIDA AP BIOLOGY – as per the newly devised topics of study focus, structure of adapted test, test dates and supports provided as per the guidelines and policies of The College Board TO ALL STUDENTS! THESE PACKETS WILL BE GUIDED BY THE SAME PROCEDURES WE EMBRACED DURING FALL TECH WEEK WHERE YOU ARE RESPONSIBLE FOR THE WORK IN THE PACKETS- DELIVERED UPON YOUR RETURN TO SCHOOL OR AS PER UNFORESEEN CHANGES WHICH COME OUR WAY. COLLABORATION IS ENCOURAGED- SO STAY IN TOUCH AND DIG IN! YOUR PACKETS WILL BE A NOTEBOOK GRADE. EVENTUALLY YOU SHALL TAKE AN INDIVIDUAL TEST OF EACH PACKET = AN EXAM GRADE! SCHOOL IS OFF SITE BUT NOT SHUT DOWN SO PLEASE DO THE BODY OF WORK ASSIGNED IN THE PACKETS PROVIDED.