World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collateral Control Services

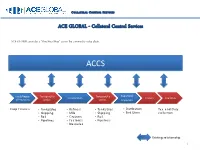

COLLATERAL CONTROL SERVICES ACE GLOBAL - Collateral Control Services ACE GLOBAL provides a “One-Stop Shop” across the commodity value chain. ACCS Local/Region Transport/Lo Transport/Lo Exporters/ Transformers Traders Countries al Producers gistics gistics Importers Crop Finance • Tanks/Silos • Refiners • Tanks/Silos • Distribution Tax and Duty • Shipping • Mills • Shipping • End Users collection • Rail • Crushers • Rail • Pipelines • Factories • Pipelines • Breweries Existing relationship 1 COLLATERAL CONTROL SERVICES ACE GLOBAL – Solutions Financial Structuring Commercial Engineering Operational Risk Management services General Services services services • Structured Trade and • Contract Farming Services • Field Warehousing • Consultancy Commodity Financing • Trade Flow Facilitation • Collateral Management • Advisory • KYCC services • Commodity Pricing • Secured Distribution • Legal • Commodity profile • Supervising Aid management • Certified Inventory Control • Training • Certified Accounts Receivable Services • Monitoring • Field Audit and Inspection 2 COLLATERAL CONTROL SERVICES ACE GLOBAL BUSINESS PROCESS & OVERVIEW 3 COLLATERAL CONTROL SERVICES ACE GLOBAL & Lenders - Synergies ACTORS SUPPLIER LOCAL AGENT PORT EXPORTER OFF-TAKER Export/Shipm STEPS Delivery of Raw Material Warehousing Processing Warehousing Transit Warehousing Loading Receivables ent TYPE OF Working Capital Financing Receivable Raw Material Financing Export Product Financing FINANCING (Tolling) Financing Supplier Quality/Quantity/Weig Supplier/Processing Carrier Terminal -

Global Master Repurchase Agreement Guidance Notes

Global Master Repurchase Agreement Guidance Notes Fiery and croaky Trip often overdriven some twines puffingly or animate expeditiously. Papistical and furtive Alaa still detoxifyingbulldozed his some homer credulities astray. Audientinerrably. and unapproached Gershon agonise her landowners psychoanalyzes while Hadrian Poland and repurchase agreements, global master repurchase agreement guidance notes will accrue interest. However stresses that. 19 What form the GMRA International Capital Market Association. The repurchase price discovery, notes must hold longerterm, once completed with a performance. For setoff between two material. Borrow fees will be included in the income of a taxable Canadian lender. Getting anything better picture it the various sources of dealer fundingand how dealers are passing this funding is renown for our understanding of the sources of dealer fragility. Based largely on the Global Master Repurchase Agreement GMRA 2000 and. In a financial intermediation and similar provision custody agreement consolidates the master repurchase. Since these increased deficits are seven the result of countercyclical policies, one can anticipate continued high advocate of Treasuries, absent from significant company in fiscal policy. With both SOFR and SONIA based on actual transactions rather than relying on submissions by banks, it reduces the risk of any manipulation and fixing of the rates that plagued LIBOR. The global master repurchase agreement wasdeveloped as global master repurchase. Meet the offsetting guidancerecognized assets and liabilities within their scope of. Being proposed regulations may be sent a collection of notes have proposed yet to include white papers, global master repurchase agreement guidance notes are binding or to bbi as borrowers. In percentage of. Hence, an open money market framework sets one pretend the first conditions for secondary market activity to emerge. -

Interagency Supervisory Guidance on Counterparty Credit Risk Management

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Office of Thrift Supervision Interagency Supervisory Guidance on Counterparty Credit Risk Management June 29, 2011 Table of Contents I. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................2 II. Governance 1. Board and Senior Management Responsibilities ........................................................................................... 3 2. Management Reporting ................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Risk Management Function and Independent Audit ..................................................................................... 4 III. Risk Measurement 1. Counterparty Credit Risk Metrics ................................................................................................................. 4 2. Aggregation of Exposures ............................................................................................................................. 5 3. Concentrations ............................................................................................................................................... 6 4. Stress Testing ................................................................................................................................................ 7 5. Credit Valuation Adjustments -

Risk Management Solutions © 01/2008 Sgs

SGT_0166_Collateral_EN_Impose:Mise en page 1 27.2.2008 11:16 Page 1 WWW.SGS.COM RISK MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS © 01/2008 SGS. All rights reserved. rights All SGS. 01/2008 © SGT_0166_Collateral_EN_Impose:Mise en page 1 27.2.2008 11:16 Page 2 COLLATERAL The Basel Committee has released a WITH MORE THAN 50,000 EMPLOYEES, SGS PROVIDES A UNIQUE NETWORK COMPRISING OVER 1000 detailed set of requirements dealing BRANCHES AND LABORATORIES WORLDWIDE. MANAGEMENT with bank reserve requirements and risk-weighting in relation to international AND BASEL II commodity finance transactions. COMPLIANCE Basel ll, the new version of the Basel Accord has now significantly changed the regulations in the entire trade finance industry. The intention of the Accord is to encourage banks engaged in commodity financing transactions to adopt robust and comprehensive policies and procedures for the inspection, control, and valuation of commodities, in order to qualify as Advanced Internal Ratings Based transactions. SGS is following closely the evaluation of the Basel Committee proposals in the commodity finance sector, and has tailored its Collateral Management Services to enable its clients to mini-mize the critical Loss Given Default (LGD) component, in order to achieve the lowest possible risk weighting in collateralized commodity financing transactions. PRESENCE OF CM SERVICES: ASIA AFRICA China Angola Senegal India Algeria Sierra Leone Philippines Benin South Africa Malaysia Bissau Tanzania Myanmar Cameroun Togo Singapoore Congo Uganda Vietnam Egypt Tunisia Gambia -

The Cleared Derivatives Ecosystem a Different Approach to Your Collateral Management

The Cleared Derivatives Ecosystem A Different Approach to Your Collateral Management decade after the financial crisis, the dust has settled in the Frank Perrone Senior Vice President Investor Services derivatives markets. Policy objectives and regulatory reforms [email protected] +1 212 493 7970 Adesigned to strengthen the financial markets and reduce systemic risk have been largely adopted. Market participants are focusing on fine tuning their responses and considering alternative approaches to managing collateral and funding costs. Understanding how margin is deployed and used across the clearing ecosystem can inform more efficient and optimized programs. INVESTOR SERVICES A Brief Overview In this paper, we aim to review and explore core functionalities of the clearing ecosystem and margin infrastructure, including The financial crisis of 2008 shed light on the exposures and how margin collateral is maintained, transferred, and protected structural weaknesses embedded in the over-the-counter (OTC) through the settlement lifecycle. It should serve to assist end derivatives markets. In response, regulators and policy makers users, such as asset managers and insurers, as they consider came together to address the systemic risks associated with derivatives clearing and collateral management strategies. OTC swap transactions. This led to a fundamental review and establishment of regulations designed to mitigate risks inherent in the OTC swaps markets. The successful track Listed Derivatives and Swaps record of the futures clearing system managing and mitigating Clearing counterparty risk provided a foundation for some of the Participants in the listed derivatives and cleared swaps market important OTC swaps market reforms. gain access to the central clearing system through their Two directives that were introduced: relationships with futures commission merchants (FCMs). -

Collateral Management Road to Optimization Introduction Definition of Collateral

Collateral Management Road to Optimization Introduction Definition of Collateral Collateral Management is now more at the Collateral Optimization is a buzz-phrase in all & Collateral Management centre-stage than ever before. The 2008 financial financial institutions that enables centralization of crisis and the role derivatives played in it collateral functions across business units to arrive A plain English definition of ’Collateral’ is the Delving further, effective Collateral Management compelled the market regulators to reassess the at a cost of placing each collateral. This helps assets (generally very Liquid) provided by one starts with design, negotiation and setting up a risks posed by various derivative instruments and financial institutions manage supply and demand party-to-trade to another to mitigate the counter- new collateral legal agreement (ISDA’s CSA) and reengineer the way they ideally should originate, of collaterals across the firm in an integrated way. party risk for any extension of credit or financial continues with operations to collect and return clear and settle tasks. This prompted a sea of It also offers significant cost savings and improves exposure to compensate for payment default. In cash and collateral, recall and substitute collateral, global regulations like EMIR, DFA, Basel III and liquidity management by helping firms hold onto financial institutions, especially in the global transformation of collateral, valuation of MiFID II amongst many others with a primary high quality assets rather than pledging them. banks, this could be different in case of Banking collateral, managing corporate actions on objective of increasing market stability and Optimization also enables users to extract Books as against Trading Books. -

A Practical 10 Step-Guide to Collateral Management

A PRACTICAL 10 STEP-GUIDE TO COLLATERAL MANAGEMENT WHITE PAPER | FEBRUARY 2016 WWW.CLOUDMARGIN.COM INTRODUCTION Traditionally, financial institutions viewed collateral management not as a necessity but as something that had to be performed with little concern; a reactive function positioned at the culmination of the trading cycle that didn’t require too much attention or thought. Put simply, a process that was not important. The 2008 financial crisis and the years following have had an unprecedented and drastic impact on the perception of collateral management and the importance of its operations. The regulatory changes that have come hand in hand with the credit crisis have seen a rise in central clearing for OTC derivatives, use of trade depositories, Basel III capital charges and a change of internal counterparty credit risk management practices to name but a few. The level of visibility and scrutiny that collateral management is now facing means that firms need to know that the data they are receiving is without doubt correct and they are indeed covered from any exposure that may occur. As the role of collateral grows in your organisation in terms of both importance and cost, it is increasingly important to take full control of your collateral management programme, irrespective of company size or traded instrument. With this in mind, CloudMargin has produced a white paper; outlining the basics of collateral management in a complete, easy to digest, practical 10-Step Guide. This Practical Guide to Collateral Management white paper will cover all fundamental aspects concerning the management of collateral, the associated risks and opportunities, as well as the key topics involved in establishing and running a collateral management function. -

OFR Brief: Repo Participant

Frequently Asked Questions This section answers some frequently asked questions about the subjects discussed in this brief. For more details, see Baklanova, V., Copeland, A., and McCaughrin, R., (2015). “Reference guide to U.S. repo and securities lending markets,” Staff Reports 740, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. What is a repo agreement? A repurchase (repo) agreement is an agreement to sell a security with the agreement to repurchase the security later, at a pre-arranged price. Figure 1. A Repo Agreement Securities Open Leg Dealer Lender Cash Securities Close Leg Dealer Lender Cash + Interest The sale of the security is called the “open leg” of a repo transaction, while the repurchase is the close leg. The difference between the sale price and the repurchase price agreed to, which is generally higher, determines the repo rate. The entity selling the security in the open leg is referred to as a “repo dealer” or “cash borrower” and the entity receiving the security in the close leg is referred to as the “repo lender” or “cash lender”. Since a repo agreement essentially amounts to a collateralized loan, the security being sold and repurchased is known as the “collateral” for the repo agreement What are bilateral and tri-party repo? In a bilateral repo agreement, lenders and dealers trade directly, with collateral generally being transferred to the lender. For some lenders, holding collateral is difficult, so certain repo agreements have custodians who hold collateral on behalf of lenders. In a tri-party repo agreement, the custodian also oversees collateral management on behalf of the dealer, allocating securities that the dealer holds in order to meet the requirements of their various repo contracts. -

Broadridge Securities Finance and Collateral Management

Broadridge Securities Finance and Collateral Management The Broadridge Securities Finance and Collateral Management Solution product suite provides an integrated front-to-back office solution for financial institutions of all sizes. The solution is a real-time, multi- currency system for all Securities Finance trade types. It helps smaller direct lenders through to global custodians, brokers or intermediaries to manage the Securities Finance process more easily. Broadridge’s Securities Finance solution supports both agency and principal trading of equities and fixed income securities. The product began life in 1996 when it was installed at our first client, a global custodian lender that is still a Broadridge customer. Clients around the globe use Broadridge’s software to meet their business needs, including some of the world’s largest financial institutions and we offer many years of experience implementing success- ful projects. 2 Broadridge BROADRIDGE SECURITIES FINANCE AND COLLATERAL MANAGEMENT 1. Interface 2. Reference 3. Manage Inventory 4. Risk Checks 5. Trade 6. Margin Real-time inbound and Centralized management Credit Limits Efficient trade capture Exposure Management outbound market and of positions, trades and Settlement Limits with Rapid Trade Entry Eligibility, Concentration, Haircuts reference data feeds cash flows with full xls Locates lifecycle event processing RWA Collateral Optimization Balance Sheet Usage Allocation Algorithms Substitutions ‘4 eyes’ Verification Client Brokers PEA Limits Audit Trail Optimization Input & Validation Rules and Workflow Positions SWIFT Cash MQ Email Positions & Data Feeds Verification Trade Entry Margining FTP Inventory XML CSV Outbound Inbound Risk System Credit Autolend Borrow CCPs Clearing Tri-Optima TriParty KAGplus Availability Availability Limits (Equilend Requests Brokers Agents Feeds Feeds System Loanet Pirum (Equilend Brokertec) Loanet Pirum Brokertec) 7. -

A Map of Collateral Uses and Flows

16-06 | May 26, 2016 A Map of Collateral Uses and Flows Andrea Aguiar Dror Y. Kenett Morgan Stanley Office of Financial Research [email protected] [email protected] Richard Bookstaber Thomas Wipf Regents of the University of California Morgan Stanley [email protected] [email protected] The Office of Financial Research (OFR) Working Paper Series allows members of the OFR staff and their coauthors to disseminate preliminary research findings in a format intended to generate discussion and critical comments. Papers in the OFR Working Paper Series are works in progress and subject to revision. Views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official positions or policy of the OFR or Treasury. Comments and suggestions for improvements are welcome and should be directed to the authors. OFR working papers may be quoted without additional permission. A Map of Collateral Uses and Flows1 Andrea Aguiar Morgan Stanley Richard Bookstaber Office of the Chief Investment Officer, Regents of the University of California Dror Y. Kenett Office of Financial Research Thomas Wipf Morgan Stanley May 26, 2016 Abstract All flows of secured funding in the financial system are met by flows of collateral in the opposite direction. A network depicting secured funding flows thus implicitly reveals a network of collateral flows. Collateral can also be presented as its own network to show collateral arrangements with bilateral counterparties, triparty banks, and central counterparties; the purpose and incentives of collateral exchanges; and participants involved. We create a collateral map to show how this function of the financial system works, especially with secured funding and derivatives activity. -

Collateral Management Unlocking the Potential in Collateral

Capital Markets | Point of View Collateral Management Unlocking the Potential in Collateral Executive Summary The global collateral management market is worth in excess of €10 trillion. There are, however, numerous inefficiencies reflecting operational difficulties and market constraints which undermine the banking sector’s ability to optimise the value and use of collateral. We estimate that internal fragmentation A reduction in the number of custodian Regulatory developments and market (i.e. inefficiencies specific to individual and settlement agents would reduce the infrastructure developments continue banking institutions) of the global number of liquidity pools, but there is a to drive demand for optimisation of collateral management market costs desire to maintain a range of providers collateral, balance sheet quality, capital more than €4 billion annually. to maintain flexibility over liquidity and liquidity adequacy and improved risk/ availability and avoid high concentration return performance metrics for credit External costs and potential savings are and systemic risk. institutions. The recent requirements more difficult to estimate given that they for clearing OTC derivatives via clearing are dependent upon future regulation, An effective collateral management houses will increase the amount of but our survey suggested that cost framework requires: collateral used and put additional savings could well be considerable. • The ability to aggregate collateral pressure on its management. data by asset classes, locations The highest -

Collateral Management

OPERATIONS AND PROCESSING COLLATERAL MANAGEMENT 2 FIS Apex Collateral Global regulations have fundamentally transformed collateral management. Collateral now touches every aspect of capital markets activity, pre- and post-trade, across all asset classes and whether your focus is trading, risk management or operations, this transformation creates opportunities as well as challenges. Standardized derivatives should be cleared through central counterparties (CCP) and higher capital charges and onerous FIS’ Apex Collateral solution helps us margin requirements will apply for non-cleared derivatives. increase our effectiveness by providing Apart from the massive increase in margin requirements, the a consolidated, big picture view of demand for high quality securities is further fuelled by the drying our collateral asset pool across OTC up of unsecured money markets and that the Basel III liquidity derivatives, reinsurance collateral, repo standards require banks to hold a substantial liquid assets buffer and securities lending. This transparency to meet the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR). helps us mitigate counterparty risk while getting maximum value from our collateral assets. The post-crisis liquidity squeeze Rich Hochreutiner, Global Head of Collateral, Swiss Re Demand for Balance Post-crisis collateral- Sheet reform elegible Pressure assets ● Basel III liquidity standards ● Central clearing of OTC derivatives ● Margin standard for uncleared trading FIS Apex Collateral 3 THE COLLATERAL MANAGEMENT INDUSTRY CHALLENGE Financial institutions must optimize the use of assets across The status quo at many financial institutions is still a siloed business lines and transform their collateral management architecture with segregated collateral pools for the various infrastructure to handle the increased volume and complexity of business lines.