Chapter 3 Transport of Gravel and Sediment Mixtures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 3D Forward Stratigraphic Model of Fluvial Meander-Bend Evolution for Prediction of Point-Bar Lithofacies Architecture

This is a repository copy of A 3D forward stratigraphic model of fluvial meander-bend evolution for prediction of point-bar lithofacies architecture. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/116031/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Yan, N orcid.org/0000-0003-1790-5861, Mountney, NP orcid.org/0000-0002-8356-9889, Colombera, L et al. (1 more author) (2017) A 3D forward stratigraphic model of fluvial meander-bend evolution for prediction of point-bar lithofacies architecture. Computers & Geosciences, 105. pp. 65-80. ISSN 0098-3004 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2017.04.012 © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Author’s Accepted Manuscript A 3D forward stratigraphic model of fluvial meander-bend evolution for prediction of point-bar lithofacies architecture Na Yan, Nigel P. -

Lesson 4: Sediment Deposition and River Structures

LESSON 4: SEDIMENT DEPOSITION AND RIVER STRUCTURES ESSENTIAL QUESTION: What combination of factors both natural and manmade is necessary for healthy river restoration and how does this enhance the sustainability of natural and human communities? GUIDING QUESTION: As rivers age and slow they deposit sediment and form sediment structures, how are sediments and sediment structures important to the river ecosystem? OVERVIEW: The focus of this lesson is the deposition and erosional effects of slow-moving water in low gradient areas. These “mature rivers” with decreasing gradient result in the settling and deposition of sediments and the formation sediment structures. The river’s fast-flowing zone, the thalweg, causes erosion of the river banks forming cliffs called cut-banks. On slower inside turns, sediment is deposited as point-bars. Where the gradient is particularly level, the river will branch into many separate channels that weave in and out, leaving gravel bar islands. Where two meanders meet, the river will straighten, leaving oxbow lakes in the former meander bends. TIME: One class period MATERIALS: . Lesson 4- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pptx . Lesson 4a- Sediment Deposition and River Structures.pdf . StreamTable.pptx . StreamTable.pdf . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pptx . Mass Wasting and Flash Floods.pdf . Stream Table . Sand . Reflection Journal Pages (printable handout) . Vocabulary Notes (printable handout) PROCEDURE: 1. Review Essential Question and introduce Guiding Question. 2. Hand out first Reflection Journal page and have students take a minute to consider and respond to the questions then discuss responses and questions generated. 3. Handout and go over the Vocabulary Notes. Students will define the vocabulary words as they watch the PowerPoint Lesson. -

Geomorphic Classification of Rivers

9.36 Geomorphic Classification of Rivers JM Buffington, U.S. Forest Service, Boise, ID, USA DR Montgomery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA Published by Elsevier Inc. 9.36.1 Introduction 730 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification 730 9.36.3 Types of Channel Classification 731 9.36.3.1 Stream Order 731 9.36.3.2 Process Domains 732 9.36.3.3 Channel Pattern 732 9.36.3.4 Channel–Floodplain Interactions 735 9.36.3.5 Bed Material and Mobility 737 9.36.3.6 Channel Units 739 9.36.3.7 Hierarchical Classifications 739 9.36.3.8 Statistical Classifications 745 9.36.4 Use and Compatibility of Channel Classifications 745 9.36.5 The Rise and Fall of Classifications: Why Are Some Channel Classifications More Used Than Others? 747 9.36.6 Future Needs and Directions 753 9.36.6.1 Standardization and Sample Size 753 9.36.6.2 Remote Sensing 754 9.36.7 Conclusion 755 Acknowledgements 756 References 756 Appendix 762 9.36.1 Introduction 9.36.2 Purpose of Classification Over the last several decades, environmental legislation and a A basic tenet in geomorphology is that ‘form implies process.’As growing awareness of historical human disturbance to rivers such, numerous geomorphic classifications have been de- worldwide (Schumm, 1977; Collins et al., 2003; Surian and veloped for landscapes (Davis, 1899), hillslopes (Varnes, 1958), Rinaldi, 2003; Nilsson et al., 2005; Chin, 2006; Walter and and rivers (Section 9.36.3). The form–process paradigm is a Merritts, 2008) have fostered unprecedented collaboration potentially powerful tool for conducting quantitative geo- among scientists, land managers, and stakeholders to better morphic investigations. -

Grain-Size Variability Within a Mega-Scale Point-Bar System, False River, Louisiana

Sedimentology (2018) doi: 10.1111/sed.12528 Grain-size variability within a mega-scale point-bar system, False River, Louisiana PETER D. CLIFT*†, ELIZABETH D. OLSON*, ALEXANDRA LECHNOWSKYJ*, MARY GRACE MORAN*, ALLISON BARBATO* and JUAN M. LORENZO* *Department of Geology and Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA (E-mail: [email protected]) †Coastal Studies Institute, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA ABSTRACT Point bars formed by meandering river systems are an important class of sedimentary deposit and are of significant economic interest as hydrocar- bon reservoirs. Standard point-bar models of how the internal sedimentol- ogy varies are based on the structure of small-scale systems with little information about the largest complexes and how these might differ. Here a very large point bar (>25Á0 m thick and 7Á5 9 13Á0 km across) on the Mis- sissippi River (USA) was examined. The lithology and grain-size character- istics at different parts of the point bar were determined by using a combination of coring and electrical conductivity logging. The data confirm that there is a general fining up-section along most parts of the point bar, with a well-defined transition from massive medium-grained sands below about 9 to 11 m depth up into interbedded silts and fine–medium sand sediment (inclined heterolithic strata). There is also a poorly defined increase in sorting quality at the transition level. Massive medium sands are especially common in the region of the channel bend apex and regions upstream of that point. Downstream of the meander apex, there is much less evidence for fining up-section. -

Stream Restoration, a Natural Channel Design

Stream Restoration Prep8AICI by the North Carolina Stream Restonltlon Institute and North Carolina Sea Grant INC STATE UNIVERSITY I North Carolina State University and North Carolina A&T State University commit themselves to positive action to secure equal opportunity regardless of race, color, creed, national origin, religion, sex, age or disability. In addition, the two Universities welcome all persons without regard to sexual orientation. Contents Introduction to Fluvial Processes 1 Stream Assessment and Survey Procedures 2 Rosgen Stream-Classification Systems/ Channel Assessment and Validation Procedures 3 Bankfull Verification and Gage Station Analyses 4 Priority Options for Restoring Incised Streams 5 Reference Reach Survey 6 Design Procedures 7 Structures 8 Vegetation Stabilization and Riparian-Buffer Re-establishment 9 Erosion and Sediment-Control Plan 10 Flood Studies 11 Restoration Evaluation and Monitoring 12 References and Resources 13 Appendices Preface Streams and rivers serve many purposes, including water supply, The authors would like to thank the following people for reviewing wildlife habitat, energy generation, transportation and recreation. the document: A stream is a dynamic, complex system that includes not only Micky Clemmons the active channel but also the floodplain and the vegetation Rockie English, Ph.D. along its edges. A natural stream system remains stable while Chris Estes transporting a wide range of flows and sediment produced in its Angela Jessup, P.E. watershed, maintaining a state of "dynamic equilibrium." When Joseph Mickey changes to the channel, floodplain, vegetation, flow or sediment David Penrose supply significantly affect this equilibrium, the stream may Todd St. John become unstable and start adjusting toward a new equilibrium state. -

Scour and Fill in Ephemeral Streams

SCOUR AND FILL IN EPHEMERAL STREAMS by Michael G. Foley , , " W. M. Keck Laboratory of Hydraulics and Water Resources Division of Engineering and Applied Science CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 91125 Report No. KH-R-33 November 1975 SCOUR AND FILL IN EPHEMERAL STREAMS by Michael G. Foley Project Supervisors: Robert P. Sharp Professor of Geology and Vito A. Vanoni Professor of Hydraulics Technical Report to: U. S. Army Research Office, Research Triangle Park, N. C. (under Grant No. DAHC04-74-G-0189) and National Science Foundation (under Grant No. GK3l802) Contribution No. 2695 of the Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology W. M. Keck Laboratory of Hydraulics and Water Resources Division of Engineering and Applied Science California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 91125 Report No. KH-R-33 November 1975 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer would like to express his deep appreciation to his advisor, Dr. Robert P. Sharp, for suggesting this project and providing patient guidance, encouragement, support, and kind criticism during its execution. Similar appreciation is due Dr. Vito A. Vanoni for his guidance and suggestions, and for generously sharing his great experience with sediment transport problems and laboratory experiments. Drs. Norman H. Brooks and C. Hewitt Dix read the first draft of this report, and their helpful comments are appreciated. Mr. Elton F. Daly was instrumental in the design of the laboratory apparatus and the success of the laboratory experiments. Valuable assistance in the field was given by Mrs. Katherine E. Foley and Mr. Charles D. Wasserburg. Laboratory experiments were conducted with the assistance of Ms. -

Sulphur Creek Sulphur Creek Has Cut a Deep Canyon That Passes Through the Oldest Rocks Exposed at Capitol Reef

Capitol Reef National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sulphur Creek Sulphur Creek has cut a deep canyon that passes through the oldest rocks exposed at Capitol Reef. It is a perennial stream with a flow that varies significantly in response to upstream water usage, snowmelt, and heavy rain. There are about two miles of scenic narrows and three small waterfalls. Bypassing the falls requires the ability to scramble down 12-foot (3.6 m) ledges. The route usually requires some walking in shallow water, but it is not uncommon for there to be much deeper water that might even require swimming. This route may be difficult for children if deep water is present. Ask at the visitor center for the latest condition report. Dangerous flash floods are an occasional hazard on this route—do not hike the Sulphur Creek route if there is a chance of rain. The 5.8-mile (9.3 km) one-way hike through Sulphur Creek Canyon involves leaving a shuttle vehicle at each end. If you don’t have two vehicles, a 3.3-mile (5.3 km) hike along Highway 24 is required to return your starting point. Vehicle shuttles are not provided or facilitated by the park. Though legal, hitchhiking is not recommended. This route is not an official, maintained trail. Route conditions, including obstacles in canyons, change frequently due to weather, flash floods, rockfall, and other hazards. Routefinding, navigation, and map-reading skills are critical. Do not rely solely on unofficial route markers (rock cairns, etc.); they are not maintained by the National Park Service (NPS), may not indicate Sulphur Creek the route in this description, or may be absent. -

Reconstructing an Extreme Flood from Boulder Transport and Rainfall–Runoff

Global and Planetary Change 70 (2010) 64–75 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global and Planetary Change journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gloplacha Reconstructing an extreme flood from boulder transport and rainfall–runoff modelling: Wadi Isla, South Sinai, Egypt Alan E. Kehew a,⁎, Adam Milewski a, Farouk Soliman b a Geosciences Dept., Western Michigan Univ., Kalamazoo, MI 49008, USA b Geology Department, Faculty of Science, Suez Canal University, Ismailia, Egypt article info abstract Article history: The Wadi Isla drainage basin, a narrow steep bedrock canyon and its tributaries, rises near the highest elevations Accepted 6 November 2009 of the Precambrian Sinai massif on the eastern margin of the tectonically active Gulf of Suez rift. The basin area Available online 17 November 2009 upstream from the mountain front is 191 km2 and downstream the wadi crosses a broad alluvial plain to the Red Sea. Stream-transported boulders within the lower canyon (up to 5 m in diameter) and in a fan downstream Keywords: indicate extremely high competence. In one reach, a 60-m-long boulder berm, ranging in height from 3 to 4 m, lies palaeoflood along the southern wall of the canyon and contains boulders 2–3 m in diameter. Boulder deposits beyond the Sinai rainfall–runoff model mouth of the canyon generally appear to be less than several metres thick and are composed of imbricated, well- boulder transport sorted boulders. The last flood that deposited these boulders is believed to have been a debris torrent with a low flash floods content of fines. Mean intermediate diameter decreases from about 1.5 m just beyond the mouth of the canyon, where the channel width expands to 300 m, to about 0.5 m downstream to the point at which the valley is no longer confined on its south side. -

Surviving a Flash Flood in a Slot Canyon

Surviving a Flash Flood in a Slot Canyon Narrow canyons can turn into sheer-walled death traps during heavy rain. Emerging from them safely depends on smart planning, constant awareness, and, when those don't work, a healthy dose of luck. By: Joe Spring for Outside Magazine On July 24, 2010, a flash flood swept 39-year-old Joe Cain and two friends through Utah's Spry Canyon and over a 40-foot cliff. He lived to talk about it—barely. Here's his story, as told to JOE SPRING. IT WAS MY FIRST TIME canyoneering. I was camping in Zion National Park with two friends, Jason Fico and Dave Frankhouser. We planned to do two canyons. The three of us had been doing outdoor stuff for a long time and we had all been rock climbing. I’d been climbing since the mid-90s. I’d been in slot canyons before, scrambling around and hiking up the narrows, and we were all very proficient about setting up rappels on anchors. The first day, July 24, we decided to do Spry Canyon. Jason had been through that canyon before. It’s a three-hour hike from the trailhead to the top where we dumped in. There were sections that you kind of scrambled through, sections you hiked through, and then a drop off with some anchors where you have to rappel. We anticipated we would be done in four hours. This was late July, 2010, monsoon season in Utah. We knew that if it rained this time of year it would probably start in mid-to-late afternoon. -

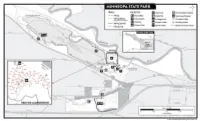

Minneopa State Park Is That Ground Wheat and Other Grains from 1864 to STATE PARK a FULL SET of STATE PARK RULES and the Third Oldest State Park in Minnesota

© 2020, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources ABOUT THE PARK SO EVERYONE CAN MINNEOPA ENJOY THE PARK... Established in 1905, Minneopa State Park is that ground wheat and other grains from 1864 to STATE PARK A FULL SET OF STATE PARK RULES AND the third oldest state park in Minnesota. It is best 1890. REGULATIONS IS AVAILABLE ONLINE. known for the double waterfall that 54497 GADWALL RD. PARK OPEN MANKATO, MN 56001 thunders during high water. The upper falls 8 a.m.–10 p.m. daily. BLUE EARTH COUNTY • 507-386-3910 [email protected] drops 7 to 10 feet and the lower falls tumbles another 40. This feature is the result of water CAMPGROUND QUIET HOURS cutting into layers of sandstone over time. 10 p.m.–8 a.m. Take the Mill Road to look for the bison, VISITOR TIPS VEHICLE PERMITS reintroduced in 2015. These animals will Required; purchase at park office or self-pay station. • Respect trail closures. naturally manage the prairie ecosystem, • Minneopa has two sections. just as they did over a hundred fifty years ago. PETS WELCOME The office and waterfall are off Near this area, you may view another Keep on 6-foot leash; leave no trace; only service animals allowed in park buildings. County Highway 69. Camping, reminder of the park’s rich history: Seppmann Don’t miss the double waterfall stone windmill, and bison are Mill. Enjoy a walk to the sandstone windmill FIREWOOD off Highway 68. Use only from approved vendors. • Minneopa Creek is not TRAIL HIGHLIGHTS recommended for swimming. -

Variability of Bed Mobility in Natural Gravel-Bed Channels

WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH, VOL. 36, NO. 12, PAGES 3743–3755, DECEMBER 2000 Variability of bed mobility in natural, gravel-bed channels and adjustments to sediment load at local and reach scales Thomas E. Lisle,1 Jonathan M. Nelson,2 John Pitlick,3 Mary Ann Madej,4 and Brent L. Barkett3 Abstract. Local variations in boundary shear stress acting on bed-surface particles control patterns of bed load transport and channel evolution during varying stream discharges. At the reach scale a channel adjusts to imposed water and sediment supply through mutual interactions among channel form, local grain size, and local flow dynamics that govern bed mobility. In order to explore these adjustments, we used a numerical flow model to examine relations between model-predicted local boundary shear stress ( j) and measured surface particle size (D50) at bank-full discharge in six gravel-bed, alternate-bar channels with widely differing annual sediment yields. Values of j and D50 were poorly correlated such that small areas conveyed large proportions of the total bed load, especially in sediment-poor channels with low mobility. Sediment-rich channels had greater areas of full mobility; sediment-poor channels had greater areas of partial mobility; and both types had significant areas that were essentially immobile. Two reach- mean mobility parameters (Shields stress and Q*) correlated reasonably well with sediment supply. Values which can be practicably obtained from carefully measured mean hydraulic variables and particle size would provide first-order assessments of bed mobility that would broadly distinguish the channels in this study according to their sediment yield and bed mobility. -

Bed Load Transport and Boundary Roughness Changes As Competing

Originally published as: Roth, D. L., Finnegan, N. J., Brodsky, E. E., Rickenmann, D., Turowski, J., Badoux, A., Gimbert, F. (2017): Bed load transport and boundary roughness changes as competing causes of hysteresis in the relationship between river discharge and seismic amplitude recorded near a steep mountain stream. ‐ Journal of Geophysical Research, 122, 5, pp. 1182—1200. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/2016JF004062 PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface RESEARCH ARTICLE Bed load transport and boundary roughness changes 10.1002/2016JF004062 as competing causes of hysteresis in the relationship Key Points: between river discharge and seismic amplitude • Hysteresis in seismic signals near rivers may not always indicate recorded near a steep mountain stream hysteresis in bed load sediment transport rates, as previously assumed Danica L. Roth1 , Noah J. Finnegan1 , Emily E. Brodsky1 , Dieter Rickenmann2 , • The seismic signal generated by water 3 2 4 turbulence, rather than sediment Jens M. Turowski , Alexandre Badoux , and Florent Gimbert transport, can dominate seismic 1 2 observations near rivers Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA, WSL Swiss Federal 3 • Shifting of grains on the river bed may Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, Birmensdorf, Switzerland, GFZ German Research Centre for change the seismic response to fluid Geosciences, Potsdam, Germany, 4University of Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IRD, IGE, Grenoble, France flow between rising and falling water levels (hysteresis) Abstract Hysteresis in the relationship between bed load transport and river stage is a well-documented phenomenon with multiple known causes. Consequently, numerous studies have interpreted hysteresis in fl Correspondence to: the relationship between seismic ground motion near rivers and some measure of ow strength (i.e., D.