Surviving a Flash Flood in a Slot Canyon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sulphur Creek Sulphur Creek Has Cut a Deep Canyon That Passes Through the Oldest Rocks Exposed at Capitol Reef

Capitol Reef National Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sulphur Creek Sulphur Creek has cut a deep canyon that passes through the oldest rocks exposed at Capitol Reef. It is a perennial stream with a flow that varies significantly in response to upstream water usage, snowmelt, and heavy rain. There are about two miles of scenic narrows and three small waterfalls. Bypassing the falls requires the ability to scramble down 12-foot (3.6 m) ledges. The route usually requires some walking in shallow water, but it is not uncommon for there to be much deeper water that might even require swimming. This route may be difficult for children if deep water is present. Ask at the visitor center for the latest condition report. Dangerous flash floods are an occasional hazard on this route—do not hike the Sulphur Creek route if there is a chance of rain. The 5.8-mile (9.3 km) one-way hike through Sulphur Creek Canyon involves leaving a shuttle vehicle at each end. If you don’t have two vehicles, a 3.3-mile (5.3 km) hike along Highway 24 is required to return your starting point. Vehicle shuttles are not provided or facilitated by the park. Though legal, hitchhiking is not recommended. This route is not an official, maintained trail. Route conditions, including obstacles in canyons, change frequently due to weather, flash floods, rockfall, and other hazards. Routefinding, navigation, and map-reading skills are critical. Do not rely solely on unofficial route markers (rock cairns, etc.); they are not maintained by the National Park Service (NPS), may not indicate Sulphur Creek the route in this description, or may be absent. -

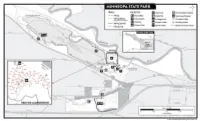

Minneopa State Park Is That Ground Wheat and Other Grains from 1864 to STATE PARK a FULL SET of STATE PARK RULES and the Third Oldest State Park in Minnesota

© 2020, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources ABOUT THE PARK SO EVERYONE CAN MINNEOPA ENJOY THE PARK... Established in 1905, Minneopa State Park is that ground wheat and other grains from 1864 to STATE PARK A FULL SET OF STATE PARK RULES AND the third oldest state park in Minnesota. It is best 1890. REGULATIONS IS AVAILABLE ONLINE. known for the double waterfall that 54497 GADWALL RD. PARK OPEN MANKATO, MN 56001 thunders during high water. The upper falls 8 a.m.–10 p.m. daily. BLUE EARTH COUNTY • 507-386-3910 [email protected] drops 7 to 10 feet and the lower falls tumbles another 40. This feature is the result of water CAMPGROUND QUIET HOURS cutting into layers of sandstone over time. 10 p.m.–8 a.m. Take the Mill Road to look for the bison, VISITOR TIPS VEHICLE PERMITS reintroduced in 2015. These animals will Required; purchase at park office or self-pay station. • Respect trail closures. naturally manage the prairie ecosystem, • Minneopa has two sections. just as they did over a hundred fifty years ago. PETS WELCOME The office and waterfall are off Near this area, you may view another Keep on 6-foot leash; leave no trace; only service animals allowed in park buildings. County Highway 69. Camping, reminder of the park’s rich history: Seppmann Don’t miss the double waterfall stone windmill, and bison are Mill. Enjoy a walk to the sandstone windmill FIREWOOD off Highway 68. Use only from approved vendors. • Minneopa Creek is not TRAIL HIGHLIGHTS recommended for swimming. -

Bed Load Transport and Boundary Roughness Changes As Competing

Originally published as: Roth, D. L., Finnegan, N. J., Brodsky, E. E., Rickenmann, D., Turowski, J., Badoux, A., Gimbert, F. (2017): Bed load transport and boundary roughness changes as competing causes of hysteresis in the relationship between river discharge and seismic amplitude recorded near a steep mountain stream. ‐ Journal of Geophysical Research, 122, 5, pp. 1182—1200. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1002/2016JF004062 PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface RESEARCH ARTICLE Bed load transport and boundary roughness changes 10.1002/2016JF004062 as competing causes of hysteresis in the relationship Key Points: between river discharge and seismic amplitude • Hysteresis in seismic signals near rivers may not always indicate recorded near a steep mountain stream hysteresis in bed load sediment transport rates, as previously assumed Danica L. Roth1 , Noah J. Finnegan1 , Emily E. Brodsky1 , Dieter Rickenmann2 , • The seismic signal generated by water 3 2 4 turbulence, rather than sediment Jens M. Turowski , Alexandre Badoux , and Florent Gimbert transport, can dominate seismic 1 2 observations near rivers Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, California, USA, WSL Swiss Federal 3 • Shifting of grains on the river bed may Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, Birmensdorf, Switzerland, GFZ German Research Centre for change the seismic response to fluid Geosciences, Potsdam, Germany, 4University of Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IRD, IGE, Grenoble, France flow between rising and falling water levels (hysteresis) Abstract Hysteresis in the relationship between bed load transport and river stage is a well-documented phenomenon with multiple known causes. Consequently, numerous studies have interpreted hysteresis in fl Correspondence to: the relationship between seismic ground motion near rivers and some measure of ow strength (i.e., D. -

Anatomy of the Nile Following the Twists and Turns of the World's Longest River

VideoMedia Spotlight Anatomy of the Nile Following the twists and turns of the world's longest river For the complete video with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.org/media/anatomy-nile/ Funder The Nile River has provided fertile land, transportation, food, and freshwater to Egypt for more than 5,000 years. Today, 95% of Egypt’s population continues to live along its banks. Where does the Nile begin? Where does it end? Watch this video, from Nat Geo WILD’s “Destination Wild” series, to find out. For an even deeper look at the Nile, use our vocabulary list and explore our “geo-tour” of the Nile to understand the geography of the river and answer the questions in the Questions tab. Questions Where is the source, or headwaters, of the Nile River? The streams of Rwanda’s Nyungwe Forest are probably the most remote sources of the Nile. The snow-capped peaks of the Rwenzori Mountains are another one of the remote sources of the Nile. The Rwenzori Mountains, sometimes nicknamed the “Mountains of the Moon,” straddle the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. Many geographers also consider Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa, to be a source of the Nile. The most significant outflow from Lake Victoria, winding northward through Uganda, is called the “Victoria Nile.” Can you find a waterfall on the Nile River? As it twists more than 6,500 kilometers (4,200 miles) through Africa, the Nile has dozens of small and large waterfalls. The most significant waterfall on the Nile is probably Murchison Falls, Uganda. -

Potential for Debris Flow and Debris Flood Along the Wasatch Front Between Salt Lake City and Willard, Utah, and Measures for Their Mitigation

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Potential for debris flow and debris flood along the Wasatch Front between Salt Lake City and Willard, Utah, and measures for their mitigation by Gerald F. Wieczorek, Stephen Ellen, Elliott W. Lips, and Susan H. Cannon U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, California and Dan N. Short Los Angeles County Flood Control District Los Angeles, California with assistance from personnel of the U.S. Forest Service Open-File Report 83-635 1983 This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, Contents Introduction Purpose, scope, and level of confidence Historical setting Conditions and events of this spring The processes of debris flow and debris flood Potential for debris flow and debris flood Method used for evaluation Short-term potential Ground-water levels Partly-detached landslides Evaluation of travel distance Contributions from channels Contributions from landslides Recurrent long-term potential Methods recommended for more accurate evaluation Mitigation measures for debris flows and debris floods Approach Existing measures Methods used for evaluation Hydrologic data available Debris production anticipated Slopes of deposition General mitigation methods Debris basins Transport of debris along channels Recommendations for further studies Canyon-by-canyon evaluation of relative potential for debris flows and debris floods to reach canyon mouths, and mitigation measures Acknowledgments and responsibility References cited Illustrations Plate 1 - Map showing relative potential for both debris flows and debris floods to reach canyon mouths; scale 1:100,000, 2 sheets Figure 1 - Map showing variation in level of confidence in evaluation of potential for debris flows and debris floods; scale 1:500,000. -

Formation of Waterfalls |Sample Answer

Formation of Waterfalls | Sample answer 2017 Q3.B Examine the impact of the processes of erosion on the formation of one fluvial landform A fluvial landform of erosion is a waterfall. A waterfall is a vertical drip in the youthful stage of a river over which a river falls, usually where a band of soft rock e.g limestone lies downstream from a band of hard rock e.g granite. The process of hydraulic action is very active in forming a waterfall. This is the sheer force of the moving water against the land. It begins as rapids on the river floor which erodes the river’s banks and bed to give rise to the vertical descent of the river’s course. As the river erodes vertically it erodes the soft rock much quicker than the harder rock which leads to differential erosion. The water in the youthful stage is very fast flowing due to the steeper gradient which then allows the water to carry rocks. This makes the process of abrasion active, as the moving rocks scrape and smoothe the river channel. The leads to the increase in the depth of the rapids and the erosive power of hydraulic action. As differential erosion continues, a small waterfall may be formed and seen within the river. The falling water then erodes a deep hole called a plunge pool at the base of the river, as the water is fast flowing and erosive because it is not hindered by friction. The river’s load is word down itself within the plunge pool due to the process of attrition, as the river’s load hits of each other, the riverbed and the back wall. -

Water Feature Costs

Water Feature Costs • Average water feature costs is between $200- 300k • Assumes: – Basic pool shape and finishes – Standard water effects, nozzles or waterfalls – Standard lighting – No interactive components – < 100’ distance to equipment space Understanding the Medium or All about Water • Terminology – Knowing the difference between water effects • Execution of effects – In order to execute you need to know how they work • How to make them work – The devil in the details • Knowing the details – Construction methods and tolerances Types of Waterfalls • Cascades – heavy flows and falls • Steps – aerated white water • Veils or Sheet falls – smooth flows • Waterwalls – Aerated – contained white water – Textured – controlled roll waves – Tension – smooth wave patterns Hydraulic Design • Waterfalls – Types: Smooth Sheets, Cascades, Steps, Waterwalls require different flow rates and physical arrangements – Flow requirements are per lineal foot but knowledge of how this translates into flow depth is important – Weir design is very important to the execution of any given water effect Flow rates for water depths • 1/8” depth = 5 gpm per lineal foot • 1/4” depth = 10 gpm per lineal foot • 1/2” depth = 17 gpm per lineal foot • 3/4” depth = 28 gpm per lineal foot • 1” depth = 40 gpm per lineal foot • 1.5” depth = 70 gpm per lineal foot • 2” depth = 105 gpm per lineal foot Shut Down Rise • Area of upper pool (ft2) x Depth of water (ft) = volume of water to catch (ft3) • Volume of water to catch (ft3) ÷ Area of lower pool = Shut down rise (ft) – Example: – Upper pool size 10 x 20 = 200 sq. ft. – Lower pool size 20 x 4 = 80 sq. -

Landforms and Waterways Archipelago: an Archipelago Is a Cluster Or Chain of Islands in the Ocean, Such As the Galapagos Or the Hawaiian Islands

Landforms and Waterways Archipelago: An Archipelago is a cluster or chain of islands in the ocean, such as the Galapagos or the Hawaiian Islands. Atoll: An atoll is a reef, which forms a ring of small islands on a coral base that surrounds a lagoon of water in an ocean. There are many atolls in the Indo-Pacific. Bay: A bay is a body of water formed by an indentation of land, but still connected to the main body of water (ocean or lake) and is smaller that a gulf, but larger than a cove. Beach: A beach runs along coastlines, lakes or rivers and is made up of sand, pebbles or rocks. Bluff: A bluff is a high, steep bank or cliff. Butte: A butte is a hill, with steep sides and a flat top that is standing out on its own. Canyon: A canyon is a deep slice of land that runs between two steep cliff walls, often carved over time by a river. Cape: A cape is a spit of land that extends out into the ocean or other bodies of water (i.e. Cape Cod) Cave: A cave is a naturally formed hollow underground. Channel: A channel is a deeper section of a river that is sought after by boats for passage or a narrow body of water that connects two large bodies of water. Cliff: A cliff is a vertical rock wall. Col: A col is the lowest point between two peaks. Continent: A continent is one of seven large landmasses on earth: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia. -

Chapter 3 Transport of Gravel and Sediment Mixtures

Parker’s Chapter 3 for ASCE Manual 54 CHAPTER 3 TRANSPORT OF GRAVEL AND SEDIMENT MIXTURES 3.1 FLUVIAL PHENOMENA ASSOCIATED WITH SEDIMENT MIXTURES When ASCE Manual No. 54, “Sedimentation Engineering,” was first published in 1975, the subject of the transport and sorting of heterogeneous sediments with wide grain size distributions was still in its infancy. This was particularly true in the case of bed- load transport. The method of Einstein (1950) was one of the few available at the time capable of computing the entire grain size distribution of particles in bed-load transport, but this capability had not been extensively tested against either laboratory or field data. Since that time there has been a flowering of research on the subject of the selective (or non-selective) transport of sediment mixtures. A brief attempt to summarize this research in a useful form is provided here. A river supplied with a wide range of grain sizes has the opportunity to sort them. While the grain size distribution found on the bed of rivers is never uniform, the range of sizes tends to be particularly broad in the case of rivers with beds consisting of a mixture of gravel and sand. These streams are termed “gravel-bed streams” if the mean or median size of the bed material is in the gravel range; otherwise they are termed “sand-bed streams.” The river can sort its gravel and sand in the streamwise, lateral and vertical directions, giving rise in each a) b) case to a characteristic Figure 3.1 Contrasts in surface armoring between a) the River morphology. -

Graphic Data & Analyzing Trends in Water Quality

Graphic Data & Analyzing Trends in Water Quality Adapted from Healthy Water, Healthy People Educators Guide – www.projectwet.org Students use a topographic map to explore the concept of a watershed and then apply that knowledge to watershed monitoring. Students will discern the difference in value between an individual data set collected at one place and time on a watershed versus a series of water quality data sets collected at various points along a watershed over time. Contents Summary and Objectives.....................................................................................Page 1 Background..........................................................................................................Page 2 Warm Up..............................................................................................................Page 3 The Activity...........................................................................................................Page 4 Sections of a River...............................................................................................Page 4 Wrap Up...............................................................................................................Page 5 Assessment & Extensions....................................................................................Page 5 River Watershed Map - Student Copy Page..........................................................Page 7 River Water Data Cards - Teacher Copy Page ....................................................Page 8 Watershed Data Summaries -

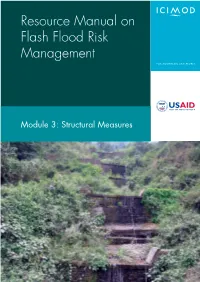

Resource Manual on Flash Flood Risk Management

Resource Manual on Flash Flood Risk Management Module 3: Structural Measures 1 About ICIMOD The International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, ICIMOD, is a regional knowledge development and learning centre serving the eight regional member countries of the Hindu Kush Himalayas – Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan – and based in Kathmandu, Nepal. Globalization and climate change have an increasing influence on the stability of fragile mountain ecosystems and the livelihoods of mountain people. ICIMOD aims to assist mountain people to understand these changes, adapt to them, and make the most of new opportunities, while addressing upstream-downstream issues. We support regional transboundary programmes through partnership with regional partner institutions, facilitate the exchange of experience, and serve as a regional knowledge hub. We strengthen networking among regional and global centres of excellence. Overall, we are working to develop an economically and environmentally sound mountain ecosystem to improve the living standards of mountain populations and to sustain vital ecosystem services for the billions of people living downstream – now, and for the future. ICIMOD gratefully acknowledges the support of its core and programme donors: the Governments of Afghanistan, Austria, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Germany, India, Myanmar, Nepal, Norway, Pakistan, Sweden, and Switzerland, and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). 2 Resource Manual on Flash Flood Risk Management Module 3: Structural Measures Arun Bhakta Shrestha Ezee GC Rajendra Prasad Adhikary Sundar Kumar Rai International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, 2012 i Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2012 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. -

Physical Features of a River

KS2 Lesson 2 Physical features of a river Describe and understand key aspects of physical geography, including rivers Geography Grammarsaurus www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 11 Think back to last lesson – what is a river? www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 12 Recap: What is a river? A river is a natural stream of water. Small rivers are also called streams, creeks and brooks. They are also natural streams of water. Rivers flow from the source (usually in the mountains) and flow through the land out to the sea. www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 13 River’s journey A river can be divided into different stages, which look and act differently. The stages are called: • upper course • middle course • lower course www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 14 Upper course The source of a river is often found in upland areas, which are mountainous and where there are steep slopes. There are high levels of precipitation, which means the high volume of water flows quickly overland and results in the fastest flow on the whole river’s journey. The river bed is rocky and narrow. As the river flows, it moves over rocks – the speed of the water creates energy and the water is powerful enough to transport material like rocks and boulders. Features in the upper course: V-shaped valleys - The river erodes as it travels and it carves the valley floor. Waterfalls - The river can erode the softer rock layers, which leaves behind an over-hang of harder rock. Tributaries – These are small rivers and/or streams that join together into the river. The more tributaries that join the river, the more powerful the speed of the river becomes as it travels.