The Use of the Hedge [From the Spirit of the Garden, 1923]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Turf Labyrinths Jeff Saward

English Turf Labyrinths Jeff Saward Turf labyrinths, or ‘turf mazes’ as they are popularly known in Britain, were once found throughout the British Isles (including a few examples in Wales, Scotland and Ireland), the old Germanic Empire (including modern Poland and the Czech Republic), Denmark (if the frequently encountered Trojaborg place-names are a reliable indicator) and southern Sweden. They are formed by cutting away the ground surface to leave turf ridges and shallow trenches, the convoluted pattern of which produces a single pathway, which leads to the centre of the design. Most were between 30 and 60 feet (9-18 metres) in diameter and usually circular, although square and other polygonal examples are known. The designs employed are a curious mixture of ancient classical types, found throughout the region, and the medieval types, found principally in England. Folklore and the scant contemporary records that survive suggest that they were once a popular feature of village fairs and other festivities. Many are found on village greens or commons, often near churches, but sometimes they are sited on hilltops and at other remote locations. By nature of their living medium, they soon become overgrown and lost if regular repair and re-cutting is not carried out, and in many towns and villages this was performed at regular intervals, often in connection with fairs or religious festivals. 50 or so examples are documented, and several hundred sites have been postulated from place-name evidence, but only eleven historic examples survive – eight in England and three in Germany – although recent replicas of former examples, at nearby locations, have been created at Kaufbeuren in Germany (2002) and Comberton in England (2007) for example. -

The Elements Are Simple

THE ELEMENTS ARE SIMPLE Rigid, lightweight panels are 48 inches wide and 6 ft, 8 ft, 10 ft, 12 ft, 14 ft long and can be installed either vertically, horizontally, wall mounted or freestanding. In addition to the standard panel, the greenscreen® system of green facade wall products includes the Column Trellis, customized Crimp-to-Curve shapes, panel trims and a complete selection of engineered attachment solutions. Customiziation and adaptation to unique project specifications can easily become a part of your greenscreen® project. The panels are made from recycled content, galvanized steel wire and finished with a baked on powder coat for durability. National Wildlife Federation Headquarters - Reston, VA basic elements greenscreen® is a three-dimensional, welded wire green facade wall system. The distinctive modular trellis panel is the building block of greenscreen.® Modular Panels Planter Options Custom Use for covering walls, Planter options are available for a Using our basic panel as the building freestanding fences, screens variety of applications and panel block, we are always available to and enclosures. heights. Standard 4 ft. wide fiberglass discuss creative options. Panels planter units support up to 6' tall can be notched, cut to create a Standard Sizes: screens, and Column planters work taper, mitered and are available in width: 48” wide with our standard diameter Column crimped-to-curve combinations. length: 6’, 8’, 10’, 12’, 14’ Trellis. Our Hedge-A-Matic family of thickness: 3" standard planters use rectangle, curved and Custom dimensions available in 2" Colors square shapes with shorter screens, increments, length and width. for venues like patios, restaurants, Our standard powder coated colors See our Accessory Items, Mounting entries and decks. -

Grow a Fence: Plant a Hedge

GARDEN NOTES GROW A FENCE: PLANT A HEDGE By Dennis Hinkamp August 2002 Fall - 45 A hedge is defined as a “fence of bushes.” However, we use them for a variety of purposes, most commonly for privacy. Tall hedges range in height from five to ten feet tall, and can be informal or formal, which does not refer to their command of etiquette, quips Jerry Goodspeed, Utah State University Extension horticulturist. Informal hedges are easier to maintain, and are the softest, least rigid in appearance. Most only require annual pruning to remove the older canes. “A few of my favorite shrubs for informal hedges include red and gold twig dogwoods, lilacs, privets and honeysuckle,” he says. “These deciduous plants make a great screen for most of the year. They are also attractive and relatively quick-growing.” For those looking for an evergreen hedge, yews, arborvitae, mugo pines or even upright junipers provide year-round cover, but also come with some inherent problems, Goodspeed says. They are more difficult to prune and maintain and do not easily relinquish stray balls and Frisbees that enter their grasp. “Formal hedges require regular haircuts to keep them looking good, and they grab anything that meanders too close,” he explains. “The most important thing to remember when pruning or shearing a formal hedge is the shape. Keep the top surface smaller than the bottom so it almost resembles a flat-topped pyramid. Cutting the sides straight or forming the top wider than the bottom provides too much shade for the lower part of the plant. -

Perhaps the Most Famous Maze in the World, the Hampton Court

• Perhaps the most famous maze in the world, the Hampton Court Palace Maze was planted in hornbeam as part of the gardens of William III and Mary II in the late 17th century. The maze was most likely planted by royal gardeners George London and Henry Wise. • The maze was planted as part of a formal garden layout known as the ‘Wilderness’ (see below). There were at least two mazes originally planted in the Wilderness garden of which the current maze is the only survivor. It is the first hedge planted maze in Great Britain and now the only part remaining of the original ‘Wilderness’ area. • Hedge mazes flourished in Britain up to the eighteenth century, until Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown introduced natural landscaping and, in order to achieve his sweeping views, destroyed many formal garden features. Ironically, as Royal Gardener for twenty years, he lived next door to the Maze at Hampton Court, but was expressly ordered not to interfere with it! • The current maze hedge was established in the 1960s when the existing hedges (a mix of hornbeam, yew, holly and privet) were replanted with fast growing yew. In 2005 hornbeam was reintroduced to the centre of the maze for the first time in 40 years. The Gardens and Estate team will regularly assess how well the hornbeam stands up to modern day wear and tear by visitors giving us the opportunity to consider reintroducing hornbeam on a wider basis to the maze in the future. • The yew hedges are approximately 7' high and 3' wide. • It is the most visited attraction in the gardens with around 350,000 people going in and out of the maze every year. -

Green Facades and Living Walls—A Review Establishing the Classification of Construction Types and Mapping the Benefits

sustainability Review Green Facades and Living Walls—A Review Establishing the Classification of Construction Types and Mapping the Benefits Mina Radi´c 1,* , Marta Brkovi´cDodig 2,3 and Thomas Auer 4,* 1 Independent Scholar, Belgrade 11000, Serbia 2 Faculty VI—Planning Building, Environment, Institute for City and Regional Planning Technical University of Berlin, 10623 Berlin, Germany 3 Faculty for Construction Management, Architecture Department, Union University Nikola Tesla, Belgrade 11000, Serbia 4 Faculty for Architecture, Technical University of Munich, 80333 München, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (T.A.); Tel.: +381-(0)63-117-2223 (M.R.); +49-(0)89-289-22475 (T.A.) Received: 21 June 2019; Accepted: 16 August 2019; Published: 23 August 2019 Abstract: The green facades and living walls of vertical greenery systems (VGS) are gaining increasing importance as sustainable building design elements because they can improve the environmental impact of a building. The field could benefit from a comprehensive mapping out of VGS types, an improved classification and nomenclature system, and from linking the benefits to a specific construction type. Therefore, this research reviews existing VGS construction types and links associated benefits to them, clearly differentiating empirical from descriptive supporting data. The study adopted a scoping research review used for mapping a specific research field. A systematic literature review based on keywords identified 13 VGS construction types—four types of green facades, nine types of living walls, and ten benefits. Thermal performance, as a benefit of VGS, is the most broadly empirically explored benefit. Yet, further qualitative studies, including human perception of thermal comfort are needed. -

The History and Development of Groves in English Formal Gardens

This is a repository copy of The history and development of groves in English formal gardens. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/120902/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Woudstra, J. orcid.org/0000-0001-9625-2998 (2017) The history and development of groves in English formal gardens. In: Woudstra, J. and Roth, C., (eds.) A History of Groves. Routledge , Abingdon, Oxon , pp. 67-85. ISBN 978-1-138-67480-6 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The history and development of groves in English formal gardens (1600- 1750) Jan Woudstra It is possible to identify national trends in the development of groves in gardens in England from their inception in the sixteenth century as so-called wildernesses. By looking through the lens of an early eighteenth century French garden design treatise, we can trace their rise to popularity during the second half of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century to their gradual decline as a garden feature during the second half of the eighteenth century. -

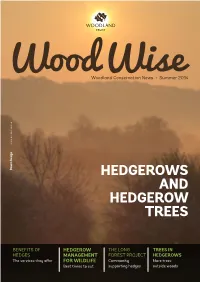

Hedgerows and Hedgerow Trees

WoodWoodland Wise Conservation News • Summer 2014 R ke C d Be R ha C WTPL, Ri Dawn hedge Dawn HEDGEROWS AND HEDGEROW TREES BENEFITS OF HEDGEROW THE LONG TREES IN HEDGES MANAGEMENT foRest PROJECT HEDGEROWS The services they offer FOR WILDLIFE Community More trees Best times to cut supporting hedges outside woods Wood Wise • Woodland Conservation News • Summer 2014 1 W o the majority due to agricultural intensification L Bag between the 1940s and 1970s. The 2007 Benefits of hedges N i L Hedgerows are important for humans and Co Countryside Survey of Great Britain found the length of ‘managed’ hedgerows declined by 6.2 wildlife; they provide a wide range of services per cent between 1998 and 2007, and only 48 that help support the healthy functioning of per cent that remained was in good structural ecosystems. condition. Wildlife services As a threatened habitat, there is a dedicated As the most widespread semi-natural habitat Hedgerow Biodiversity Action Plan. The in the UK, hedgerows support a large diversity original Habitat Action Plan (HAP) only covered of flora and fauna. There are 130 Biodiversity ancient and/or species rich hedges, but this Action Plan species closely associated with was increased to include all hedgerows where hedges and many more that use them for food at least one native woody tree or shrub was and/or shelter during some of their lifecycle. dominant (at least 80 per cent of the hedge). They are a good source of food (flowers, berries and nuts) for invertebrates, birds and mammals. In intensively farmed areas they Hedgerow trees offer a refuge for wild plants and animals. -

Low Maintenance Gardening

LOW MAINTENANCE GARDENING FOR LOADS OF BEAUTY & HEALTH IN A NUTSHELL - DESIGN AND REDESIGN WITH MAINTENANCE AND ENJOYMENT IN MIND Utility-friendly Tree Planting Tips ๏ LESS IS MORE from We Energies ๏ MAKE IT EASY ๏ DO THE GROUNDWORK Trees growing too close to power lines ๏ CHOOSE WISELY can cause sparks, fires, power outages ๏ TREAT THEM RIGHT and shock hazards. To avoid these ๏ GARDEN WITH EASE problems, plant trees that won’t ๏ WARM UP, TAKE BREAKS AND BE SAFE interfere with power lines when fully grown. Small ornamental trees or LESS IS MORE shrubs that will not exceed 15 feet in height such as serviceberry, dogwood • Start small and expand as time, energy and desire allow and low-growing evergreens are best Fewer and smaller beds to plant around power lines. Trees Easy access to all parts of the garden bed and surrounding landscape such as maple, basswood, burr oak, • Fewer species - more of each white pine or spruce grow more than Low Maintenance Design Tips 40 feet high and should be planted Design with Maintenance in Mind more than 50 feet from any overhead • Simple combinations to double impact and create interest power lines. Plants flower at same time to double interest Plants flower at different times to extend bloom time And don’t forget to call 811 at least Make it edible and attractive - foodscaping three days before planting to check • Proper spacing the location of underground services. Shrub Plantings with Big Impact in a Short Time Use annuals and perennials as fillers as trees and shrubs grow Learn more utility-friendly planting You’ll need fewer annuals each year tips at we-energies.com. -

Education Ireland." for Volume See .D 235 105

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 248 188 SO 015 902 AUTHOR McKirnan, Jim, Ed. TITLE Irish Educational Studies, Vol. 3 No. 2. INSTITUTION Educational Studies Association of Ireland, Ddblin. PUB DATE 83 NOTE 3t3k Financial assistance provided by Industrial Credit. Corporation (Ireland), Allied Irish Banks, Bank ot Ireland, and "Education Ireland." For Volume see .D 235 105. For Volume 3 no. 1, see SO 015 901. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bt3iness Education; Case Studies; Comparative Education; Computer Assisted Instructkon; Educational Finance; *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Educational Theories; Elementary Secondaiy Education; Foreign Countries; High School Graduate0; National Programs; Open Education; ParochialSchools; Peace; Private Schools; Reading Instruction; Science Education IDENTIFIERS *Ireland; *Northern Ireland ABSTRACT Research problems and issues of concern to educators in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland are discussed in 21 papers. Papers fall into the general categorie3 of educational history and current practices. Papers in the first category cover the following topics: a history'oflthe Education Inquiry of 1824-1826, the "hedge" or private primary schools which existed in Ireland prior to institution of the national school system in 1831, the relationship between the Chriptian Brothers schools and the national school system, the relationship between the Irish treasury and the national school system, a history of the Royal.Commission -

E PARK of RUNDĀLE PALACE the Grounds of Rundāle Palace Ensemble Amount to Shuvalov Ordered Chestnut Tree Alleys to Be Planted the Eighteenth Century

LAYOUT OF THE RUNDĀLE PALACE BAROQUE GARDEN 20 20 !e Park 14 14 of Rundāle Palace 15 16 19 11 12 18 13 17 5 6 9 8 8 7 10 4 3 2 2 1 Entrance 1 Ornamental parterre 2 Rose garden Ticket o"ce 3 Collection of peonies 4 Blue Rose Garden Information 5 Picnic Area 6 Bosquet of Decorative Souvenirs Fruit Trees Exhibition 7 Blue Bosquet 8 Bosquets of Lilacs Study room 9 Dutch Bosquet 10 Green Theatre Indoor plants 11 Bosquet of Lilies 12 Memorial Bosquet Café 13 Oriental Bosquet Drinking water 14 Bosquets of Blooming Trees and Shrubs Toilets 15 Golden Vase Bosquet 16 Bosquet of Hydrangeas 17 Water Fountain Bosquet 18 Playground Bosquet 19 Labyrinth Bosquet 20 Promenade Bosquets in a formative stage RUNDĀLES PILS MUZEJS Pilsrundāle, Rundāles novads, LV-3921, Latvija T. +371 63962274, +371 63962197, +371 26499151, [email protected], www.rundale.net © Rundāles pils muzejs, 2018 The location map of Rundāle Palace The baroque garden of Rundāle Palace Climbing-rose arcade Pavilion in the Picnic Area Pavilion in the Oriental Bosquet Memorial Bosquet by Rastrelli, 1735/1736 THE PARK OF RUNDĀLE PALACE The grounds of Rundāle Palace ensemble amount to Shuvalov ordered chestnut tree alleys to be planted the eighteenth century. Donations made by visitors have to reconstruct it in order to nurture plants required for 85 hectares including the French baroque garden which beside the palace, yet the last remnants of theses alleys made it possible to build both a historical seesaw and the garden as well as to provide winter storage for covers 10 hectares and fully retains its original layout were removed in 1975. -

Product Guide Bring Walls to Life

PRODUCT GUIDE BRING WALLS TO LIFE EXPLORE VISTAGREEN P. 6-7 OUR PHILOSOPHY P. 8-9 A PERSONAL TOUCH The market leader in artificial green walls P. 10-11 THE MOST BEAUTIFUL GREEN WALLS P. 12-15 RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT P. 16-19 THE VISTAGREEN DIFFERENCE P. 20-69 VISTAGREEN AT HOME Contents P. 70-71 VISTAGREEN FOR BUSINESS P. 72-85 Hospitality P. 86-95 Events & Exhibitions P. 96-99 Airports P. 100-105 Shopping Centres P. 106-113 Where horticultural limits are reached, our artificial Furniture Stores green walls are the market-leading solution for P. 114-125 Offices spaces where plants cannot grow. P. 126-127 Casinos | 5 PAGE Our green walls transcend the need for light and P. 128-129 OUR PRODUCTS PAGE | 4 PAGE water and are at home anywhere your imagination P. 130-135 CUSTOMISE YOUR GREEN WALL takes them. Manufacturing our Signature Panels to the highest standards in our own facility, we have faithfully replicated nature’s beauty using colours and forms virtually indistinguishable from real plants. PRODUCED BY: VISTAGREEN CREATIVE TEAM UK ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE USED IN ANY FORM OR MEANS WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN CONSENT OF VISTAGREEN LTD. COPYRIGHT © 2019, VISTAGREEN LIMITED. IF YOU HAVE ANY QUESTIONS PLEASE CONTACT: UNIT 6 TRADE CITY FRIMLEY, LYON WAY, FRIMLEY, CAMBERLEY GU16 7AL UNITED KINGDOM TEL +44 (0)20 7385 1020 VISTAGREEN LTD. BRING WALLS TO LIFE PAGE | 7 PAGE PAGE | 6 PAGE OUR PHILOSOPHY At Vistagreen, we are driven by the passion We constantly innovate to ensure that our to create inspiring, uplifting environments products are an exciting blend of high style that will enhance and enrich everyday life. -

Seattle Green Factor Walls Presentation

GREEN WALLS and GREEN TOWERS Presented by Randy Sharp, ASLA, CSLA, LEED® Accredited Professional Sharp & Diamond Landscape Architecture Inc. GREEN WALLS and GREEN TOWERS GREEN CITY VISIONS Atlanta, GA www.nasa.gov Vancouver, BC: Pacific Boulevard, by Alan Jacobs Chicago: Kennedy Expressway • Green corridor with large urban trees for airflow • Competition by Perkins and Will • Green roofs and living walls control microclimate GREEN WALLS and GREEN TOWERS URBAN TREES and PERMEABLE PAVERS SF-RIMA Uni Eco-Stone pavers • Porous pavements give urban trees the rooting space they need to grow to full size. (Bruce K. Ferguson, and R. France, Handbook of Water Sensitive Planning and Design, 2002) • Large trees reduce ambient temperature by 9F (5C) by evapotranspiration and shading. GREEN WALLS and GREEN TOWERS COOL PAVERS and CONTINUOUS SOIL TRENCHES Ithaca, New York: pavers with soil trench Berlin, by Daniel Roehr • 5th Avenue, New York, trees are 100+ years. Trees store more than 2000 kg. of carbon. • Durability and flexibility: These sidewalk pavers are 60+ years. • Permeable pavers allow air, water and nutrients down to roots. Avoid sidewalk heaving. GREEN WALLS and GREEN TOWERS BIOCLIMATIC SKYSCRAPERS, Ken Yeang, Architect Menara Mesiniaga, Malaysia, photo by Ken Yeang IBM Plaza, Drawing by Ken Yeang Bioclimatic skyscraper by T.R. Hamzah & Yeang • T.R. Hamzah & Yeang design bioclimatic buildings for tropical and temperate zones. • Bioclimatic Skyscrapers in Malaysia are a form of regional architecture. • Lower building costs and energy consumption. Aesthetic and ecological benefits. • Passive approach: sun shading, louvers, solar skycourts, terraces, wind catchers. • Green roofs connected to the ground and to green corridors.