Species Diversity and Conservation Status Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01-Marty 148.Indd

Copy proofs - 2-12-2013 Bull. Soc. Herp. Fr. (2013) 148 : 419-424 On the occurrence of Dendropsophus leali (Bokermann, 1964) (Anura; Hylidae) in French Guiana by Christian MARTY (1)*, Michael LEBAILLY (2), Philippe GAUCHER (3), Olivier ToSTAIN (4), Maël DEWYNTER (5), Michel BLANC (6) & Antoine FOUQUET (3). (1) Impasse Jean Galot, 97354 Montjoly, Guyane française [email protected] (2) Health Center, 97316, Antécum Pata, Guyane française (3) CNRS Guyane USR 3456, Immeuble Le Relais, 2 avenue Gustave Charlery, 97300 Cayenne, Guyane française (4) Ecobios, BP 44, 97321, Cayenne CEDEX , Guyane française (5) Biotope, Agence Amazonie-Caraïbes, 30 domaine de Montabo, Lotissement Ribal, 97300 Cayenne, Guyane française (6) Pointe Maripa, RN2/PK35, Roura, Guyane française Summary – Dendropsophus leali is a small Amazonian tree frog occurring in Brazil, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia where it mostly inhabits patches of open habitat and disturbed forest. We herein report five new records of this species from French Guiana extending its range 650 km to the north-east and sug- gesting that D. leali could be much more widely distributed in Amazonia than previously thought. The origin of such a disjunct distribution pattern probably lies in historical fluctuations of the forest cover during the late Tertiary and the Quaternary. Poor understanding of Amazonian species distribution still impedes comprehensive investigation of the processes that have shaped Amazonian megabiodiversity. Key-words: Dendropsophus leali, Anura, Hylidae, distribution, French Guiana. Résumé – À propos de la présence de Dendropsophus leali (Bokermann, 1964) (Anura ; Hylidae) en Guyane française. Dendropsophus leali est une rainette de petite taille présente au Brésil, au Pérou, en Bolivie et en Colombie où elle occupe principalement des habitats ouverts ou des forêts perturbées. -

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 123 (2018) 59–72

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 123 (2018) 59–72 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Phylogenetic relationships and cryptic species diversity in the Brazilian egg- T brooding tree frog, genus Fritziana Mello-Leitão 1937 (Anura: Hemiphractidae) ⁎ Marina Walker1, , Mariana L. Lyra1, Célio F.B. Haddad Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia and Centro de Aquicultura (CAUNESP), Campus Rio Claro, Av. 24A,No 1515, Bela Vista, CEP 13506-900 Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The genus Fritziana (Anura: Hemiphractidae) comprises six described species (F. goeldii, F. ohausi, F. fissilis, F. Egg-brooding frogs ulei, F. tonimi, and F. izecksohni) that are endemic to the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Although the genus has been Molecular phylogeny the subject of studies dealing with its taxonomy, phylogeny, and systematics, there is considerable evidence for Brazilian Atlantic Forest cryptic diversity hidden among the species. The present study aims to understand the genetic diversity and Species diversity phylogenetic relationships among the species of Fritziana, as well as the relationships among populations within New candidate species species. We analyzed 107 individuals throughout the distribution of the genus using three mitochondrial gene Mitochondrial gene rearrangements fragments (12S, 16S, and COI) and two nuclear genes (RAG1 and SLC8A3). Our data indicated that the species diversity in the genus Fritziana is underestimated by the existence of at least three candidate species hidden amongst the group of species with a closed dorsal pouch (i.e. F. fissilis and F. ulei). We also found four species presenting geographical population structures and high genetic diversity, and thus require further investigations. -

For Review Only

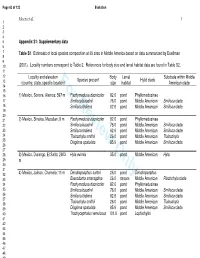

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Mannophryne Olmonae) Catherine G

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2014 A Not-So-Silent Spring: The mpI acts of Traffic Noise on Call Features of The loB ody Bay Poison Frog (Mannophryne olmonae) Catherine G. Clemmens The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Clemmens, Catherine G., "A Not-So-Silent Spring: The mpI acts of Traffico N ise on Call Features of The loodyB Bay Poison Frog (Mannophryne olmonae)" (2014). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 5783. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/5783 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2014 Catherine G. Clemmens A NOT-SO-SILENT SPRING: THE IMPACTS OF TRAFFIC NOISE ON CALL FEATURES OF THE BLOODY BAY POISON FROG (MANNOPHRYNE OLMONAE) DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY INDEPENDENT STUDY THESIS Catherine Grace Clemmens Adviser: Richard Lehtinen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Independent Study Thesis in Biology at the COLLEGE OF WOOSTER 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ABSTRACT II. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………...............…...........1 a. Behavioral Effects of Anthropogenic Noise……………………….........2 b. Effects of Anthropogenic Noise on Frog Vocalization………………....6 c. Why Should We Care? The Importance of Calling for Frogs..................8 d. Color as a Mode of Communication……………………………….…..11 e. Biology of the Bloody Bay Poison Frog (Mannophryne olmonae)…...13 III. -

Species Diversity and Conservation Status of Amphibians in Madre De Dios, Southern Peru

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 4(1):14-29 Submitted: 18 December 2007; Accepted: 4 August 2008 SPECIES DIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF AMPHIBIANS IN MADRE DE DIOS, SOUTHERN PERU 1,2 3 4,5 RUDOLF VON MAY , KAREN SIU-TING , JENNIFER M. JACOBS , MARGARITA MEDINA- 3 6 3,7 1 MÜLLER , GIUSEPPE GAGLIARDI , LILY O. RODRÍGUEZ , AND MAUREEN A. DONNELLY 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, OE-167, Miami, Florida 33199, USA 2 Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Avenida Arenales 1256, Lima 11, Perú 4 Department of Biology, San Francisco State University, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, California 94132, USA 5 Department of Entomology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, California 94118, USA 6 Departamento de Herpetología, Museo de Zoología de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana, Pebas 5ta cuadra, Iquitos, Perú 7 Programa de Desarrollo Rural Sostenible, Cooperación Técnica Alemana – GTZ, Calle Diecisiete 355, Lima 27, Perú ABSTRACT.—This study focuses on amphibian species diversity in the lowland Amazonian rainforest of southern Peru, and on the importance of protected and non-protected areas for maintaining amphibian assemblages in this region. We compared species lists from nine sites in the Madre de Dios region, five of which are in nationally recognized protected areas and four are outside the country’s protected area system. Los Amigos, occurring outside the protected area system, is the most species-rich locality included in our comparison. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Etar a Área De Distribuição Geográfica De Anfíbios Na Amazônia

Universidade Federal do Amapá Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Tropical Mestrado e Doutorado UNIFAP / EMBRAPA-AP / IEPA / CI-Brasil YURI BRENO DA SILVA E SILVA COMO A EXPANSÃO DE HIDRELÉTRICAS, PERDA FLORESTAL E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS AMEAÇAM A ÁREA DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ANFÍBIOS NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA MACAPÁ, AP 2017 YURI BRENO DA SILVA E SILVA COMO A EXPANSÃO DE HIDRE LÉTRICAS, PERDA FLORESTAL E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS AMEAÇAM A ÁREA DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ANFÍBIOS NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Tropical (PPGBIO) da Universidade Federal do Amapá, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em Biodiversidade Tropical. Orientador: Dra. Fernanda Michalski Co-Orientador: Dr. Rafael Loyola MACAPÁ, AP 2017 YURI BRENO DA SILVA E SILVA COMO A EXPANSÃO DE HIDRELÉTRICAS, PERDA FLORESTAL E MUDANÇAS CLIMÁTICAS AMEAÇAM A ÁREA DE DISTRIBUIÇÃO DE ANFÍBIOS NA AMAZÔNIA BRASILEIRA _________________________________________ Dra. Fernanda Michalski Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP) _________________________________________ Dr. Rafael Loyola Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) ____________________________________________ Alexandro Cezar Florentino Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP) ____________________________________________ Admilson Moreira Torres Instituto de Pesquisas Científicas e Tecnológicas do Estado do Amapá (IEPA) Aprovada em de de , Macapá, AP, Brasil À minha família, meus amigos, meu amor e ao meu pequeno Sebastião. AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a CAPES pela conceção de uma bolsa durante os dois anos de mestrado, ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biodiversidade Tropical (PPGBio) pelo apoio logístico durante a pesquisa realizada. Obrigado aos professores do PPGBio por todo o conhecimento compartilhado. Agradeço aos Doutores, membros da banca avaliadora, pelas críticas e contribuições construtivas ao trabalho. -

AMPHIBIANS of the RIOZINHO Do ANFRÍSIO Extractive Reserve,Pará

WEB VERSION PARÁ STATE, Eastern Amazon, BRAZIL AMPHIBIANS of the RIOZINHO do ANFRÍSIO Extractive Reserve, Pará 1 Flávio Bezerra Barros1,2; Luís Vicente2 and Henrique M. Pereira2 1Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil; 2Centro de Biologia Ambiental, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal Photos by Flávio Bezerra Barros, except where indicated. Produced by Tyana Wachter, J. Philipp, & R. Foster, with support from Ellen Hyndman Fund & Andrew Mellon Foundation. © Flávio Bezerra Barros [[email protected]] Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil; Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal © Environmental & Conservation Programs, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [[email protected]] [www.fmnh.org/animalguides/] Rapid Color Guide # 271 version 1 08/2010 1 Allophryne ruthveni 2 Allobates femoralis 3 Allobates sp. 4 Dendrophryniscus bokermanni ALLOPHRYNIDAE AROMOBATIDAE AROMOBATIDAE BUFONIDAE (carrying tadpoles) 5 Rhaebo guttatus 6 Rhinella castaneotica 7 Rhinella magnussoni 8 Rhinella gr. margaritifera BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE 9 Rhinella gr. margaritifera 10 Rhinella marina 11 Rhinella marina 12 Ceratophrys cornuta BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE BUFONIDAE CERATOPHRYIDAE (pair in amplexus) (pair in amplexus) 13 Proceratophrys concavitympanum 14 Adelphobates castaneoticus 15 Dendropsophus brevifrons 16 Dendropsophus leucophyllatus CYCLORAMPHIDAE DENDROBATIDAE HYLIDAE HYLIDAE photo: Pedro L.V. Peloso 17 Dendropsophus leucophyllatus 18 Dendropsophus leucophyllatus 19 Dendropsophus melanargyreus 20 Dendropsophus minusculus HYLIDAE HYLIDAE HYLIDAE HYLIDAE (yellow pattern) (giraffe pattern) WEB VERSION PARÁ STATE, Eastern Amazon, BRAZIL AMPHIBIANS of the RIOZINHO do ANFRÍSIO Extractive Reserve, Pará 2 Flávio Bezerra Barros1,2; Luís Vicente2 and Henrique M. Pereira2 1Universidade Federal do Pará, Brazil; 2Centro de Biologia Ambiental, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal Photos by Flávio Bezerra Barros, except where indicated. -

Foam Nest Construction and First Report of Agonistic Behaviour In

Neotropical Biology and Conservation 14(1): 117–128 (2019) doi: 10.3897/neotropical.14.e34841 SHORT COMMUNICATION Foam nest construction and first report of agonistic behaviour in Pleurodema tucumanum (Anura, Leptodactylidae) Melina J. Rodriguez Muñoz1,2, Tomás A. Martínez1,2, Juan Carlos Acosta1, Graciela M. Blanco1 1 Gabinete DIBIOVA (Diversidad y Biología de Vertebrados del Árido). Departamento de Biología, FCEFN, Universidad Nacional de San Juan, Avenida Ignacio de la Roza 590, Rivadavia J5400DCS, San Juan, Argentina 2 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Godoy Cruz 2290, C1425FQB, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires Argentina Corresponding author: Melina J. Rodriguez Muñoz ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. M. Leal-Zanchet | Received 21 May 2018 | Accepted 27 December 2018 | Published 11 April 2019 Citation: Rodriguez Muñoz MJ, Martínez TA, Acosta JC, Blanco GM (2019) Foam nest construction and first report of agonistic behaviour in Pleurodema tucumanum (Anura: Leptodactylidae). Neotropical Biology and Conservation, 14(1): 117–128. https://doi.org/10.3897/neotropical.14.e34841 Abstract Reproductive strategies are the combination of physiological, morphological, and behavioural traits interacting to increase species reproductive success within a set of environmental conditions. While the reproductive strategies of Leiuperinae are known, few studies have been conducted regarding the reproductive behaviour that underlies them. The aim of this study was to document the structural characteristics of nesting microsites, to describe the process of foam nest construction, and to explore the presence of male agonistic and chorus behaviour in Pleurodema tucumanum. Nests were found close to the edge of a temporary pond and the mean temperature of the foam nests was always close to the mean temperature of the pond water. -

Cop18 Doc. 62 (Rev

Original language: Spanish CoP18 Doc. 62 (Rev. 1) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Colombo (Sri Lanka), 23 May – 3 June 2019 Species specific matters DRAFT DECISIONS ON THE CONSERVATION OF AMPHIBIANS (AMPHIBIA) 1. This document has been submitted by Costa Rica.* 2. Amphibians are the most threatened class of vertebrates worldwide. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, "of the 6260 amphibian species assessed, nearly one-third of species (32.4 %) are globally threatened or extinct, representing 2030 species". This is considerably higher than the comparable figure for birds (13 %) or mammals (22 %) (IUCN Red List 2016). The number of species classified as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable has increased throughout the world due to a number of threats, including habitat loss, trade, and disease. While loss of habitat and disease are considered to be the major threats to amphibian populations, harvesting for human use is a further pressure, sometimes posing the greatest threat (IUCN, 2016). 3. Amphibians occur throughout the world, with diversity nuclei in Central America, South America, East and Central Africa, East and South Asia, and Madagascar (Abraham et al. 2013; Jenkins et al. 2013; Pratihar et al. 2014; Pimm et al. 2014, among other authors). Amphibians live in a variety of terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, ranging from tropical forests to deserts (Stuart et al. 2008). 4. Amphibians have been an important part of human culture for millennia and traditionally served as a source of food (e.g., Mohneke et al. -

Chromosome Analysis of Five Brazilian

c Indian Academy of Sciences RESEARCH ARTICLE Chromosome analysis of five Brazilian species of poison frogs (Anura: Dendrobatidae) PAULA CAMARGO RODRIGUES1, ODAIR AGUIAR2, FLÁVIA SERPIERI1, ALBERTINA PIMENTEL LIMA3, MASAO UETANEBARO4 and SHIRLEI MARIA RECCO-PIMENTEL1∗ 1Departamento de Anatomia, Biologia Celular e Fisiologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 13083-863 Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil 2Departamento de Biociências, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Campus Baixada Santista, 11060-001 Santos, São Paulo, Brazil 3Coordenadoria de Pesquisas em Ecologia, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas do Amazonas, 69011-970 Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil 4Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, 70070-900 Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil Abstract Dendrobatid frogs have undergone an extensive systematic reorganization based on recent molecular findings. The present work describes karyotypes of the Brazilian species Adelphobates castaneoticus, A. quinquevittatus, Ameerega picta, A. galactonotus and Dendrobates tinctorius which were compared to each other and with previously described related species. All karyotypes consisted of 2n = 18 chromosomes, except for A. picta which had 2n = 24. The karyotypes of the Adelphobates and D. tinctorius species were highly similar to each other and to the other 2n = 18 previously studied species, revealing conserved karyotypic characteristics in both genera. In recent phylogenetic studies, all Adelphobates species were grouped in a clade separated from the Dendrobates species. Thus, we hypothesized that their common karyotypic traits may have a distinct origin by chromosome rearrangements and mutations. In A. picta, with 2n = 24, chromosome features of pairs from 1 to 8 are shared with other previously karyotyped species within this genus. Hence, the A. -

Anura: Hylidae) Author(S): Victor G

The Taxonomic Status of Dendropsophus allenorum and Dendropsophus timbeba (Anura: Hylidae) Author(s): Victor G. D. Orrico , William E. Duellman , Moisés B. Souza , and Célio F. B. Haddad Source: Journal of Herpetology, 47(4):615-618. 2013. Published By: The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1670/12-208 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1670/12-208 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 47, No. 4, 615–618, 2013 Copyright 2013 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles The Taxonomic Status of Dendropsophus allenorum and Dendropsophus timbeba (Anura: Hylidae) 1,2 3