The Chad Conflict, United Nations (MINURCAT) and the European Union (EUFOR)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arms Exports and Transfers

ARMS EXPORTS AND TRANSFERS: EUROPE TO AFRICA, BY COUNTRY December 2010 Study realized by Africa Europe Faith and Justice Network – AEFJN AEFJN Report Arms exports from Europe to Africa 1/37 ARMS EXPORTS AND TRANSFERS: EUROPE TO AFRICA, BY COUNTRY 1. General overview Selling and transferring arms to the African market is a very profitable endeavor for many European countries and companies. For example, Russia, the second largest arms exporter after the United States, sent 14% of its arms and weapons exports for 2005-2009 to Africa, its second largest market. In the same time period, German arms exports to Africa increased by 100% from 2000-2004, and French exports increased by 30%. It is important to note that a majority of the defense materials, aircraft, and vehicles that are sent to Africa are refurbished or second-hand; many are remnants of Cold War era militarization, particularly the arms from Eastern European countries such as Ukraine. During the period 2005-2009, South Africa and the North African countries of Algeria, Morocco, Libya, and to a lesser extent, Egypt and Tunisia, are the largest arms importers in Africa. There is a definite trend indicating an ominous North African arms race with Algeria at the forefront. And while the exports from Europe to Sub-Saharan Africa are not nearly comparable in scope or scale as their northern neighbors, SIPRI reports that “in several cases, relatively small volumes of arms supplies to Sub-Saharan African countries have had a major impact on regional conflict dynamics.” The issue of exporting arms to a country only to have them redistributed to conflict zones is very real and highlights the importance of verifying end-user. -

Inhoud Rhetoric Or Restraint

RHETORIC OR RESTRAINT? Trade in military equipment under the EU transfer control system A Report to the EU Presidency NOVEMBER 2010 Edited by An Vranckx, Confl ict Research Group University of Ghent Published with generous support of Belgian Federal Service of Foreign Affairs, Peace-building department Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust Academia Press, Gent RHETORIC OR RESTRAINT? 1 Printed by Academia Press, Gent (Belgium) ISBN 978 90 382 1693 5 U 1522 D/2010/4804/242 Cover design by Studio Kmzero, Firenze www.studiokmzero.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including pho- tocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher or the author. 2 RHETO R I C O R R EST R AINT? Executive Summary More than two decades ago, EU Member States began developing a common framework to ensure their decision-making on military exports took into account political and moral concerns that were being raised in their constituencies. The Code of Conduct for European Union countries’ exports of military technology and equipment, which was put into place in 1998, represented a major milestone in that process. A decade later, the EU Code was cast in concrete when it was transformed into a legally-binding Common Position. While the system is a distinct improvement on what went before, and the level of control exercised in the EU is in many ways setting the global lead, the EU system is still far from perfect. In some cases this would appear to be because licensing authorities are not applying the rules with sufficient rigour; in others because the rules themselves are inadequate to the task. -

Instability and Humanitarian Conditions in Chad

Instability and Humanitarian Conditions in Chad Lauren Ploch Analyst in African Affairs July 1, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS22798 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Instability and Humanitarian Conditions in Chad Summary As the Sahel region weathers another year of drought and poor harvests, the political and security situation in Chad remains volatile, compounding a worsening humanitarian situation in which some 2 million Chadians are at risk of hunger. In the western Sahelian region of the country, the World Food Program warns that an estimated 60% of households, some 1.6 million people, are currently food insecure. Aid organizations warn that the situation is critical, particularly for remote areas in the west with little international aid presence, and that the upcoming rainy season is likely to further complicate the delivery of assistance. In the east, ethnic clashes, banditry, and fighting between government forces and rebel groups, both Chadian and Sudanese, have contributed to a fragile security situation. The instability has forced over 200,000 Chadians from their homes in recent years. In addition to the internal displacement, over 340,000 refugees from the Central African Republic (CAR) and Sudan’s Darfur region have fled violence in their own countries and now live in refugee camps in east and southern Chad, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). With Chadian security forces stretched thin, the threat of bandit attacks on the camps and on aid workers has escalated. The instability has also impacted some 700,000 Chadians whose communities have been disrupted by fighting and strained by the presence of the displaced. -

The Maba People & Chad's Ouaddaï Region

THE MABA PEOPLE & CHAD’S OUADDAÏ REGION The Maba People and Chad’s Ouaddaï Region © Center for the Study of Global Christianity, 2020 Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary Cover Photo: Refugees from Darfur in eastern Chad, 2011 | globalnyt.dk: European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. (CC BY-SA 2.0) Unless otherwise noted, data is sourced from the World Christian Database and the fol- lowing citation should be used: Todd M. Johnson and Gina A. Zurlo, eds., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, accessed December 2019). ABOUT THE CSGC The Center for the Study of Global Christianity is an academic research center that mon- itors worldwide demographic trends in Christianity, including outreach and mission. We provide a comprehensive collection of information on the past, present, and future of Christianity in every country of the world. Our data and publications help churches, mission agencies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to be more strategic, thoughtful, and sensitive to local contexts. Please visit our website at www.globalchristianity.org. DATA AND TERMS This dossier includes many technical terms related to the presentation of statistics. A complete methodology document is found here: https://www.gordonconwell.edu/ center-for-global-christianity/research/dossiers. We use a social scientific method for measuring religion around the world; namely, self-identification. If a person calls herself a Christian, then she is a Christian. We measure Christians primarily by denominational affiliation in every country of the world and these data are housed in the World Christian Database. Ethnolinguistic people groups are distinct homogeneous ethnic or racial groups within a single country, speaking its own language (one single mother tongue). -

On the Record

On the Record An audit of Canada’s report on military exports, 2003-05 By Kenneth Epps & Kyle Gossen January 2009 Project Ploughshares On the Record An audit of Canada’s report on military exports, 2003–05 By Kenneth Epps & Kyle Gossen About this Publication In this publication, Project Ploughshares provides detailed analysis of the “Report on Exports of Military Goods from Canada, 2003-2005,” published by the Export Controls Division of Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. Kyle Gossen conducted research and co-authored the publication during a term placement under the Co-operative Education program at the University of Waterloo. Kenneth Epps is Senior Program Associate with Project Ploughshares. Project Ploughshares Project Ploughshares is the ecumenical peace centre of The Canadian Council of Churches established to work with churches and related organizations, as well as governments and nongovernmental organizations, in Canada and internationally, to identify, develop, and advance approaches that build peace and prevent war. Project Ploughshares is affiliated with the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Conrad Grebel University College, University of Waterloo. Project Ploughshares 57 Erb Street West Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2 Canada 519-888-6541 Fax 519-888-0018 [email protected] www.ploughshares.ca The views presented in this paper do not necessarily reflect the policies of the sponsoring churches of Project Ploughshares. © Project Ploughshares 2009 ISBN 978-1-895722-73-4 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Why an Audit 3 2A. Introduction 3 2B. Canada and the International Arms Trade 4 2C. Auditing the “Annual” Report 5 2D. Methodology 7 3. -

At Half-Strength, Un Mission in Central African Republic, Chad Has Limited Ability

28 July 2009 Security Council SC/9718 Department of Public Information • News and Media Division • New York Security Council 6172nd Meeting (AM) AT HALF-STRENGTH, UN MISSION IN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC, CHAD HAS LIMITED ABILITY TO EXECUTE MILITARY CONCEPT, OFFER SAFETY TO AID WORKERS, SECURITY COUNCIL TOLD Once fully deployed, the United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT) would be sure to make a difference, the top United Nations official on the ground told the Security Council today. Updating the Council on the developments since authority was transferred from the European Union-led EUFOR bridge force to the United Nations on 15 March, Victor Da Silva Angelo, Special Representative of the Secretary-General and Head of the United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT), said that the Force now stood at 46 per cent of its mandated strength. Its slow deployment had limited its ability to effectively execute the military concept of operations and to provide the required safe environment for humanitarian workers, refugees, internally displaced and vulnerable persons, he said. The Secretary-General, in the report before the Council today, stated that in order for MINURCAT to achieve its full force projection and capability, pledges were urgently needed to provide it with needed “enablers”, including 14 of the 18 required military helicopters. While encouraged by recent pledges of troops to replace those departing the Mission, the Secretary-General was also concerned by delays in deployment, which risked creating security gaps. He encouraged Member States to assist troop-contributing countries in acquiring the necessary equipment and expediting the deployment of their contingents. -

Blood at the Crossroads: Making the Case for a Global Arms Trade Treaty 2

BLOOD AT THE CROSSROADS MAKING THE CASE FOR A GLOBAL ARMS TRADE TREATY Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion – funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Amnesty International Publications First published in 2008 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org © Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2008 Index: ACT 30/011/2008 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Cover photo: A US soldier aims his weapon at a man who has just been shot by another soldier for failing to stop in Mosul, northern Iraq, on 23 July 2003. US troops had been on high alert in the area after a shootout the previous day in which two sons of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein were killed. © AP Photo/Wally Santana TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................5 -

Right Tech Solutions for USAF

SMALL WARS JOURNAL smallwarsjournal.com “Right Tech” Solutions for USAF Security Force Assistance by Mike Lydon I ask you to think through what more we might do—through training and equipping programs, or other initiatives—to enhance the air capabilities of other nations and whether, for example, we should pursue a conceptual ‘100-wing air force’ of allies and partners to complement the ‘1,000-ship navy’ now being leveraged across the maritime commons. - Robert M. Gates, 18 Apr 08 The Services have been charged with a new mission for the 21st century. This mission is to Build Partnerships and Build Partnership Capacity (Security Force Assistance (SFA)) around the world11. Much of this work will be conducted in countries characterized by crushing poverty, lack of resources, and an unemployed youth bulge generating associated terrorism. This is not uncharted territory for the military; we have conducted years of similar work since the end of World War II. Korea was less developed than Ghana in the early 50‟s;2 Taiwan was a poor island full of refugees after the fall of the nationalist government, while from the 1990‟s through today European Command works with former Warsaw Pact nations through the Partnership for Peace program (PfP). PfP was effectively used to diffuse a tense situation by partnering, engaging and mentoring the countries cut loose by the dissolution of the USSR. To conduct the SFA mission the USAF needs the ways and means to engage some of the fragile, failed or failing states that can still generate international threats within their ungoverned spaces. -

Mikoyan Mig-29 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "Mig-29" Redirects Here

Mikoyan MiG-29 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "MiG-29" redirects here. For other uses, see MiG-29 (disambiguation). The Mikoyan MiG-29 (Russian: Микоян МиГ-29; NATO reporting name: "Fulcrum") is a twin-engine jet fighter aircraft MiG-29 designed in the Soviet Union. Developed by the Mikoyan design bureau as an air superiority fighter during the 1970s, the MiG-29, along with the larger Sukhoi Su-27, was developed to counter new American fighters such as the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle, and the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon.[6] The MiG-29 entered service with the Soviet Air Force in 1983. While originally oriented towards combat against any enemy aircraft, many MiG-29s have been furnished as multirole fighters capable of performing a number of different operations, and are commonly outfitted to use a range of air-to- surface armaments and precision munitions. The MiG-29 has been manufactured in several major variants, including the multirole Mikoyan MiG-29M and the navalised Mikoyan MiG-29K; the most advanced member of the family to date is the Mikoyan MiG-35. Later models frequently feature improved engines, glass cockpits with HOTAS-compatible flight controls, modern radar and IRST sensors, and considerably increased fuel capacity; some aircraft have also been equipped for aerial refuelling. Serbian Air Force and Air Defence MiG-29 Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the militaries of a number of former Soviet republics have continued to takeoff operate the MiG-29, the largest of which is the Russian Air Force. The Russian Air Force wanted to upgrade its existing Role Air superiority fighter, fleet to the modernised MiG-29SMT configuration, but financial difficulties have limited deliveries. -

Disputes Non-Violent Crises Violent Crises Limited Wars Wars 27

2018 disputes non-violent crises violent crises limited wars wars No. 27 Copyright © 2019 HIIK All rights reserved. Printed in Heidelberg, Germany. The Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research (HIIK), associated with the Institute of Political Science of Heidelberg University, is a registered non-profit association. It is dedicated to the research, evaluation, and documentation of political conflicts worldwide. The HIIK evolved from the 1991 research project COSIMO (Conflict Simulation Model), led by Prof. Dr. Frank R. Pfetsch, University of Heidelberg, and financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG). For more information please visit our website: www.hiik.de HIIK Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research CONFLICT BAROMETER I 2018 Analyzed Period: 01/01/18 – 12/31/18 PREFACE With the 27th edition of the Conflict Barometer, teh H IIK continues its annual series of reports covering political conflicts worldwide. The global political conflict panorama in 2018 was marked by reverse trends. While the overall number of wars clearly decreased, the number of limited wars significantly increased. In Asia, Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa, wars de-escalated, such as in Myanmar, Ukraine, DR Congo, and South Sudan. In contrast, three limited wars intensified to full-scale wars in the Middle East Northern Africa (MENA) region, seeing escalations on Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, in Syria’s Afrin region, and in the conflict between Turkey and the Kurdistan’s Workers’ Party (PKK). In spite of these changes, many conflicts maintained their intensity, such as the wars in Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Libya, Central African Republic, Somalia, and Nigeria, or, for instance, the limited wars in Brazil, Colombia, and the Philippines. -

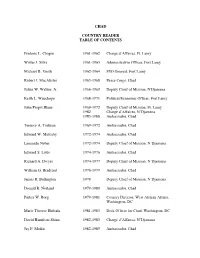

Table of Contents

CHAD COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Frederic L. Chapin 1961-1962 Chargé d’Affaires, Ft. Lamy Walter J. Silva 1961-1963 Administrative Officer, Fort Lamy Michael B. Smith 1962-1964 FSO General, Fort Lamy Robert J. MacAlister 1965-1968 Peace Corps, Chad Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1966-1969 Deputy Chief of Mission, N'Djamena Keith L. Wauchope 1968-1971 Political/Economic Officer, Fort Lamy John Propst Blane 1969-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ft. Lamy 1982 Charge d’Affaires, N’Djamena 1985-1988 Ambassador, Chad Terence A. Todman 1969-1972 Ambassador, Chad Edward W. Mulcahy 1972-1974 Ambassador, Chad Leonardo Neher 1972-1974 Deputy Chief of Mission, N’Djamena Edward S. Little 1974-1976 Ambassador, Chad Richard A. Dwyer 1974-1977 Deputy Chief of Mission, N’Djamena William G. Bradford 1976-1979 Ambassador, Chad James R. Bullington 1979 Deputy Chief of Mission, N’Djamena Donald R. Norland 1979-1980 Ambassador, Chad Parker W. Borg 1979-1981 Country Director, West African Affairs, Washington, DC Marie Therese Huhtala 1981-1983 Desk Officer for Chad, Washington, DC David Hamilton Shinn 1982-1983 Chargé d’Affaires, N’Djamena Jay P. Moffat 1982-1985 Ambassador, Chad Richard W. Bogosian 1990-1992 Ambassador, Chad Franklin E. Huffman 1999-2000 Public Affairs Officer, N’Djamena Christopher E. Goldthwait 1999-2004 Ambassador, Chad FREDERIC L. CHAPIN Chargé d’Affaires Ft. Lamy (1961-1962) Ambassador Frederic L. Chapin joined the Foreign Service in 1952. His career included posts in Austria, Nicaragua, Brazil, El Salvador, and ambassadorships to Ethiopia and Guatemala. Ambassador Chapin was interviewed by Ambassador Horace G. Torbert in 1989. -

Hiscox WTPV Aug 2009.Indd

AUGUST 2009 Table of contents Transnational terrorism 2 Profi le: The Jakarta attacks 3 Worldwide terrorist activity 4 Africa Americas Asia Europe Middle East and North Africa In-depth 8 Coming up 9 A forensic investigator examines debris inside the Ritz-Carlton hotel INDONESIA A suspected suicide bomber early on 17 July detonated his explosives near the Lobby Lounge restaurant in the Ritz-Carlton hotel in the capital Jakarta. A second explosion occurred at the JW Marriott (which suffered an attack in 2003) and is also thought to have been perpetrated by a suicide bomber. A third bomber also reportedly checked into the JW For more information about Hiscox or Control Marriott with the two known attackers; police subsequently defused another Risks, please contact: bomb at the hotel. Retribution for the execution last year of three men Stephen Ashwell accused of involvement in the 2002 Bali bombings was a potential motive. Tel: 020 7448 6725 1 Great St Helen’s, London EC3A 6HX The attacks bore the hallmarks of fringe extremist elements within regional [email protected] extremist network Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), which have continued to promote www.hiscox.com violent jihad even though JI as a whole has sought to move towards the political mainstream since the last large-scale attacks in Indonesia in 2005. Peter Simpson Veteran bomb-maker Noordin Top – one of South-east Asia’s most wanted Tel: 020 7970 2373 terrorists – has been identifi ed as a likely leader. The attacks all but confi rm Cottons Centre, Cottons Lane, fears that radical JI factions are still highly active and may have revived London SE1 2QG funding and resource networks that counter-terrorism operations in recent [email protected] years are thought to have heavily disrupted.