S.NO. Appl.No. Name of the Candidate 1 1 KORLAM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BC Agents Deployed by the Bank

ZONE_NAM SOL_I STATE_NAME E DIST Mandal BASE_BRANCH D VILLAGE_NAME Bank Mitr Name AGENT ID Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 EACHANERI L Somasekhar FI2056105194 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 KATTAKINDAPALLE C Padma FI2056108800 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 MADHAVARAM M POORNIMA FI2056102033 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Aragonda Aragonda 0561 PAIMAGHAM N Joshua Paul FI2056105191 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Irala Irala 0594 ERLAMPALLE Subhasini G FI2059410467 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Irala Irala 0594 Pathapalem G Surendra Babu FI2059408801 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Irala Irala 0594 Venkata Samudra AgraharamP Bhuvaneswari FI2059405192 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Chittoor Nagalapuram Nagalapuram 0590 Baithakodiembedu P Santhi FI2059008839 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Krishna Surampalli Surampalli 1496 CHIKKAVARAM L Nagendra babu FI2149601676 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Krishna Thotavalluru Thotavalluru 0476 BhadriRajupalem J Sowjanya Laxmi FI2047605181 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Krishna Thotavalluru Thotavalluru 0476 BODDAPADU Chekuri Suryanarayana FI2047608950 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD MEDAK_OLD PATANCHERUVU PATANCHERUVU 1239 Kardanur Auti Rajeswari FI2123908799 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD MEDAK_OLD SANGAREDDY SANGAREDDY 0510 Kalabgor Ayyam Mohan FI2051008798 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD MEDAK_OLD SANGAREDDY SANGAREDDY 0510 TADLAPALLE Malkolla Yashodha FI2051008802 Andhra Pradesh HYDERABAD Visakahaptnam Devarapally Devarapally 0804 CHINANANDIPALLE G.Dhanalaxmi -

GUDLAVALLERU ENGINEERING COLLEGE (An Autonomous Institute with Permanent Affiliation to JNTUK, Kakinada) Seshadri Rao Knowledge Village :: Gudlavalleru

GUDLAVALLERU ENGINEERING COLLEGE (An Autonomous Institute with Permanent Affiliation to JNTUK, Kakinada) Seshadri Rao Knowledge Village :: Gudlavalleru. Students Summary sheet for the Academic Year 2015-16 S.no Program Final Year B.Tech 1 CIVIL 133 2 EEE 176 3 ME 190 4 ECE 206 5 CSE 180 6 IT 49 Total 934 M.Tech 7 CIVIL-SE 24 8 EEE-PEED 21 9 EEE-CS 11 10 ME-MD 11 11 ECE-ES 19 12 ECE-DECS- 20 13 CSE-CSE- 35 Total 141 MBA 14 MBA 89 GUDLAVALLERU ENGINEERING COLLEGE (An Autonomous Institute with Permanent Affiliation to JNTUK, Kakinada) Seshadri Rao Knowledge Village, Gudlavalleru – 521356, Krishna District (A.P.) Ac. Yr: 2019-20 NOMINAL ROLLS IV B. -

Daddy (2001 Film)

Daddy (2001 film) Daddy (Telugu: ) is a 2001 Telugu film. The movie • Kota Srinivasa Rao as Shanti’s Paternal Uncle É stars Chiranjeevi and Simran. It was produced by Allu • Allu Arjun as Gopi (guest role) Aravind on the Geetha Arts banner under the direction of Suresh Krishna. The film was successful at the box • Achyuth as Ramesh office. It was released on 4 October 2001. • M. S. Narayana as Priya’s Father • Uttej as Priya’s Friend 1 Plot • Director: Suresh Krishna Raj Kumar or Raj (Chiranjeevi) is a rich audio com- • Writers: Bhupathi Raja (story), Satyanand (dia- pany owner who owns a modern dance school. Dance logue) and Suresh Krishna (screenplay) is his passion and his life till he meets and marries Shanti • Producer: Allu Aravind (Simran). They have a daughter Akshaya (Anushka Mal- hotra). Raj believes in his friends and does anything for • Music: S. A. Rajkumar them. However, they take advantage of him and usurp • his wealth. Though Raj and his family are happy in their Cinematography: Chota K. Naidu not-so-lavish lifestyle, their happiness is shattered when • Fights: Vikram Dharma and Pawan Kalyan Akshaya becomes ill with a heart condition. Raj instead of bringing the money Shanti had stored in the bank to • Choreography: Saroj Khan and Raju Sundaram the hospital to save Akshaya, uses it to save his former • Executive producer: Nagaraju Chittajallu dance student Gopi (Allu Arjun), who was hit by a car. Shanti, who is pregnant, leaves him because she feels that • Editor: Marthand K. Venkatesh he killed their daughter. • Art: Ashok Six years later, Raj, who is once again wealthy, sees his second child, Aishwarya (Anushka Malhotra), who looks exactly like his Akshaya, in whose honor he builds a foun- 3 Commercial dation which takes care of poor, unhealthy children and their families. -

Inoperative Sb

INOPERATIVE SB ACCOUNTS SL NO ACCOUNT NUMBER CUSTOMER NAME 1 100200000032 SURESH T R 2 100200000133 NAVEEN H N * 3 100200000189 BALACHARI N M * 4 100200000202 JAYASIMHA B K 5 100200000220 SRIVIDHYA R 6 100200000225 GURURAJ C S * 7 100200000236 VASUDHA Y AITHAL * 8 100200000262 MUNICHANDRA M * 9 100200000269 VENKOBA RAO K R 10 100200000272 VIMALA H S 11 100200000564 PARASHURAMA SHARMA V * 12 100200000682 RAMDAS B S * 13 100200000715 SHANKARANARAYANA RAO T S 14 100200000752 M/S.VIDHYANIDHI - K.S.C.B.G.O. * 15 100200000768 SESHAPPA R N 16 100200000777 SHIVAKUMAR N * 17 100200000786 RAMYA VIJAY 18 100200000876 GIRIRAJ G R 19 100200000900 LEELAVATHI C S 20 100200000926 SARASWATHI A S * 21 100200001019 NAGENDRA PRASAD S 22 100200001037 BHANUPRAKASHA H V * 23 100200001086 GURU MURTHY K R * 24 100200001109 VANISHREE V S * 25 100200001183 VEENA SURESH * 26 100200001207 KRISHNA MURTHY Y N 27 100200001223 M/S.VACHAN ENTERPRISES * 28 100200001250 DESHPANDE M R 29 100200001272 ARJUN DESHPANDE * 30 100200001305 PRASANNA KUMAR S 31 100200001333 CHANDRASHEKARA H R 32 100200001401 KUMAR ARAGAM 33 100200001472 JAYALAKSMAMMA N * 34 100200001499 MOHAN RAO K * 35 100200001517 LEELA S JAIN 36 100200001523 MANJUNATH S BHAT 37 100200001557 SATYANARAYANA A * 1 38 100200001559 SHARADAMMA S * 39 100200001588 RAGHOTHAMA R * 40 100200001589 SRIDHARA RAO B S * 41 100200001597 SUBRAMANYA K N * 42 100200001635 SIMHA V N * 43 100200001656 SUMA PRAKASH 44 100200001679 INDIRESHA T V * 45 100200001691 AJAY H A 46 100200001718 VISHWANATH K N 47 100200001733 SREEKANTA MURTHY -

Megastar: Chiranjeevi and Telugu Cinema After NT Ramo

1 Whistling Fans and Conditional Loyalty hat can cinema tell us about the politics of our time? There can of Wcourse be little doubt that studies of the cinema, from Siegfried Kracauer's magnum opus on German cinema (2004) to M.S.S. Pandian's (1992) study of MGR, have attempted to answer precisely this question. The obscene intimacy between film and politics in southern India provides an opportunity for students of cinema to ask the question in a manner that those in the business of studying politics would have to take seriously. This chapter argues that this intimacy has much to do with the fan-star relationship. Chiranjeevi's career foregrounds the manner in which this relationship becomes one of the important distinguishing features of Telugu cinema, as also a key constituent of the blockage that it encounters. Earlier accounts of random by social scientists (Hardgrave Jr. 1979, Hardgrave Jr. and Niedhart 1975, and Dickey 1993: 148-72) do not ponder long enough upon this basic question of how it is a response to the cinema. As a consequence, their work gives the impression that the fan is a product of everything (that is, religion, caste, language, political movements) but the cinema. I will argue instead that the engagement with cinema's materiality—or what is specific to die cinema: filmic texts, stars and everything else that constitutes thjs industrial-aesthetic form—is crucial for comprehending random. STUDYING FANS Fans' associations (FAs) are limited to south Indian states.1 Historically speaking, however, some of the earliest academic studies of Indian 4 Megastar Whistling Fans and Conditional Loyalty 5 popular cinema were provoked, at least in part, by the south Indian occasion to discuss (mis) readings of audiences at some length in the star-politician and his fans (for example, Hardgrave Jr. -

Commencement ’17

COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE, PLANNING AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Commencement ’17 Friday, May 12, 2017 • 11 a.m. • College Park Center the university of texas at arlington “AS YOU LEAVE THESE HALLOWED HALLS, REMEMBER THAT AS MAVERICKS WE STRIVE FOR WHAT OTHERS MAY CONSIDER IMPOSSIBLE. SPREAD YOUR WINGS AND REACH FOR THE STARS. NEVER BE SCARED OF STRETCHING BEYOND YOUR BOUNDS—YOUR ABILITIES ARE CONSTRAINED ONLY BY THE LIMITS YOU SET FOR YOURSELF.” —UTA President Vistasp M. Karbhari ProgrAm College of ArChiteCture, PlAnning And PubliC AffAirs sChool of soCiAl Work university College THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON COMMENCEMENT CEREMONY Prelude UTA Jazz Orchestra Conducted by Tim Ishii, Director of Jazz Studies The Academic Procession Degree Candidates, Faculty, and Platform Party University Marshal Lisa Nagy Interim Vice President for Student Affairs, UTA Entrance of the National Colors UTA Army ROTC Color Guard Call to Order Dr. Ronald L. Elsenbaumer Interim Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, UTA National Anthem UTA Jazz Orchestra Michael Daugherty, Vocals Welcome and Introductions Dr. Nan Ellin Dean, College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs Commencement Address Randall C. Gideon, FAIA Presentation and Recognition of Candidates Dr. Ellin Dr. Scott D. Ryan Dean, School of Social Work Dr. Pranesh B. Aswath Vice Provost for Academic Planning and Policy, UTA Hooding of Doctoral Degree Candidates Dr. Ardeshir Anjomani Dr. Rod Hissong Dr. Enid Arvidson Dr. John Bricout Dr. Noelle Fields Dr. Rebecca Hegar Dr. Mike Killian Dr. Diane Mitschke Dr. Ann Nordberg Dr. Vijayan Pillai Dr. Regina Praetorius Dr. Alexa Smith-Osborne Master’s Degree Candidates Bradley Bell David Hopman Dr. -

Computer Application (Self Financing

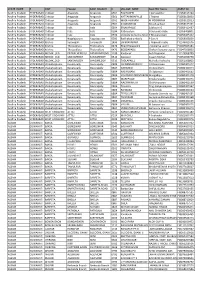

SACRED HEART COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) THEVARA Trial Rank List B COM COMPUTER APPLICATION-SELF-FINANCE Rank Applicant No Applicant Name Category Index Mark 1 3002015 SWATHY RAVEENDRAN OTHER BACKWARD HINDU 920 2 3006133 MABLEMOL PRASAD GENERAL 915 ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 3 3001399 ANCHU MATHEW 915 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 4 3006393 ROSIT MARIYA MATHEW 915 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY 5 3000006 MISHA JOBY GENERAL 915 6 3001963 NANDHANA THANKACHAN SCHEDULED CASTE 915 7 3000261 NAVIYA ANNA VARKEY GENERAL 914 8 3001450 FIDAH PAROL SHANAVAS MUSLIM 914 ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 9 3001997 DEEPTHY DAVIS 914 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 10 3000180 THERESA SABU 914 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 11 3000074 SERIN STEPHY 914 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY 12 3001256 NISHANA FEBIN AP MUSLIM 914 13 3000475 BISMITHA MUJEEB MUSLIM 913 14 3003268 ARCHANA K K EZHAVA, THIYYA AND BILLAVA (ETB) 913 LATIN CATHOLIC OTHER THAN 15 3003622 TREAZA HELEN 912 ANGLO INDIAN 16 3004624 ARYA.K.A EZHAVA, THIYYA AND BILLAVA (ETB) 912 17 3003851 JAHANA SHIRIN P S MUSLIM 912 18 3005327 GIFTY CLEETUS GENERAL 912 19 3002638 SURYA . R . S OTHER BACKWARD HINDU 912 ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 20 3000203 ROSE MARY JOHNSON 912 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY 21 3001078 GOURY PRIYA SHIBU EZHAVA, THIYYA AND BILLAVA (ETB) 912 22 3006345 MURALI KRISHNAN C S GENERAL 911 23 3005976 SIJO CHERIAN PANICKER GENERAL 911 24 3001581 CHAITHANYA C EZHAVA, THIYYA AND BILLAVA (ETB) 910 ROMAN CATHOLIC SYRIAN 25 3002253 MERIN ROSE 910 CATHOLIC COMMUNITY 26 3000336 HANNA SARA RENIL GENERAL 910 27 3000015 KEZIA ALICE -

Banner Name Proprietor Partner BANNER LIST

BANNER LIST Banner Name Proprietor Partner 1234 Cine Creations C.R.Loknath Anand L 1895 Dec 28 the World Ist Movie Production S.Selvaraj No 2 Streams Media P Ltd., Prakash Belavadi S.Nandakumar 21st Century Lions Cinema (P) Ltd., Nagathihalli Chandrashekar No 24 Frames Pramodh B.V No 24 Frames Cine Combines Srinivasulu J Gayathri 24 Frames Movie Productions (p) Ltd K.V.Vikram Dutt K.Venkatesh Dutt 3A Cine Productions Sanjiv Kumar Gavandi No 4D Creations Gurudatta R No 7 Star Entertainment Studios Kiran Kumar.M.G No A & A Associates Aradhya V.S No A B M Productions P.S.Bhanu Prakash P.S.Anil Kumar A' Entertainers Rajani Jagannath J No A Frame To Frame Movies Venkatesh.M No A.A.Combines Praveen Arvind Gurjer N.S.Rajkumar A.B.C.Creations Anand S Nayamagowda No A.C.C.Cinema - Shahabad Cement Works. M.N.Lal T.N.Shankaran A.G.K.Creations M.Ganesh Mohamad Azeem A.J.Films R.Ashraf No A.K.Combines Akbar Basha S Dr. S.R.Kamal (Son) A.K.Films Syed Karim Anjum Syed Kalimulla A.K.K. Entertainment Ltd Ashok Kheny A.Rudragowda (Director) A.K.N.D.Enterprises - Bangalore N.K.Noorullah No A.L.Films Lokesh H.K No A.L.K.Creations C.Thummala No A.M.J.Films Janardhana A.M No A.M.M.Pictures Prakash Babu N.K No A.M.M.Pictures Prakash Babu N.K No A.M.Movies Nazir Khan No A.M.N.Film Distributor Syed Alimullah Syed Nadimullah A.M.V.Productions Ramu V No A.N.Jagadish Jagadish A.N Mamatha A.J(Wife) A.N.Pictures U.Upendra Kumar Basu No A.N.Ramesh A.N.Ramesh A.R.Chaya A.N.S.Cine Productions Sunanda M B.N.Gangadhar (Husband) A.N.S.Films Sneha B.G B.N.Gangadhar (Father) A.N.S.Productions Gangadhar B.N No A.P.Helping Creations Annopoorna H.T M.T.Ramesh A.R.Combines Ashraf Kumar K.S.Prakash A.R.J.Films Chand Pasha Sardar Khan A.R.Productions K.S.Raman No A.R.S.Enterprises H.M.Anand Raju No A.S.Films Noorjhan Mohd Asif A.S.Ganesha Films Dr.T.Krishnaveni No A.S.K.Combines Aruni Rudresh No A.S.K.Films A.S.Sheela Rudresh A.S.Rudresh A.T.R.Films Raghu A.T. -

The Rhetoric of Masculinity and Machismo in the Telugu Film Industry

TAMING OF THE SHREW: THE RHETORIC OF MASCULINITY AND MACHISMO IN THE TELUGU FILM INDUSTRY By Vishnupriya Bhandaram Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisors: Vlad Naumescu Dorit Geva CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2015 Abstract Common phrases around the discussion of the Telugu Film Industry are that it is sexist and male-centric. This thesis expounds upon the making and meaning of masculinity in the Telugu Film Industry. This thesis identifies and examines the various intangible mechanisms, processes and ideologies that legitimise gender inequality in the industry. By extending the framework of the inequality regimes in the workplace (Acker 2006), gendered organisation theory (Williams et. al 2012) to an informal and creative industry, this thesis establishes the cyclical perpetuation (Bourdieu 2001) of a gender order. Specifically, this research identifies the various ideologies (such as caste and tradition), habituated audiences, and portrayals of ideal masculinity as part of a feedback loop that abet, reify and reproduce gender inequality. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements “It is not that there is no difference between men and women; it is how much difference that difference makes, and how we choose to frame it.” Siri Hustvedt, The Summer Without Men At the outset, I would like to thank my friends old and new, who patiently listened to my rants, fulminations and insecurities; and for being agreeable towards the unreasonable demands that I made of them in the weeks running up to the completion of this document. -

The NEET PG Rank Wise List of Canidates Who Studied MBBS In

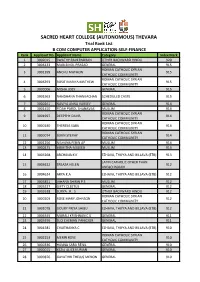

Dr. NTR UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES, VIJAYAWADA -8 As per the data received from the Ministry of Health , Government of India, the following is the NEET PG Rank wise list of canidates who studied MBBS in the State of Andhra Pradesh ( Based on the information provided by the candidates in the application form) and appeared for NEET PG 2020 conducted by NBE. Cut off Marks for Eligibility under General Category is 366 Marks, For PH category 342 Marks, for BC,SC,ST categories 319 Marks Note 1 : This is only for information of Students and Parents Note 2 : The final Merit position will be displayed only after submission of online application in response to the University Notification and after verification of original certificates/ eligibility as per rules NEET - S.No ROLL NO NAME OF THE CANDIDATE SCORE RANK 1 2066161932 CHAPPA PRAVALLIKA 938 41 2 2066015456 POTHIREDDY SHARANYA 931 56 3 2066090034 KOULALI SAI SAMARTH 931 61 4 2066153442 P SOWMYA 930 66 5 2066114879 PASUMARTHY SAI SRI HARSHA 926 79 6 2066056289 GUDIMETLA PRIYANKA 925 80 7 2066054521 ACHUTHA DATTATREYA 924 84 8 2066090718 SYED KHALEELULLAH 910 149 9 2066056746 DALLI SURESH 909 152 10 2066062929 TALASILA NAGA BHAVANI KRISHNA 903 190 11 2066090361 SANA ASFIYA 898 223 12 2066162715 NOUDURI VENKATA ABHISHEK 898 224 13 2066112146 N S L SUSMITHA 894 260 14 2066060592 SADHU KEERTHI 892 278 15 2066055410 CHEBOLU HARSHIKA 890 287 16 2066044484 BHAVANA CHANDA 888 314 17 2066062582 MANGALA THANMAYEE 887 319 18 2066044988 SHAIK MOHAMMAD KHASIM 887 325 19 2066056960 SAAHITI SUNKARA 885 -

Twenty 20 Malayalam Full Movie

Twenty 20 malayalam full movie Continue Twenty:20Official theatrical posterFoshiProduced byDileep Written byUdayakrishnaSiby K. ThomasStarringMohanlalMammoottySuresh GopiJayaramDileepMusic fromSur PetereshsBerny IgnatiusCinematographyP.SukumarEditedRan by Abraham Abraham and production DistributedManjunatha release Kalasangham FilmsRelease date November 5, 2008 (2008-11-05) Duration 165 minutesCountryIndiaLanguageMalayalamBudget₹7 crore (US$980,000)Box officeest. ₹32.6 crora ($4.6 million) is a 2008 Indian action film in Malayalam, written by Udayakrishna and Sibi K. Thomas and directed by Josh. The film stars Mohanlal, Mammutti, Suresh Gopi, Jayaram and Dillep, and was produced and distributed by actor Dillep through Graand Production and Manjunatha Release. The film was produced on behalf of the Association of Malayalam Film Chronicles (AMMA) as a fundraiser to financially support actors who are struggling in the Malayalam film industry. All AMMA members worked without pay to raise funds for their Social Security programs. The film features an ensemble of actors, which includes almost all AMMA artists. The music was written by Bernie-Ignatius and Suresh Peters. The share of the first two weeks of the film's distributors was ₹5.72 crore ($800,000). The film managed to gain a foothold in the third position (with 7 prints, 4 in Chennai) in the box office of Tamil Nadu in the first week. The total number of introductory engravings produced inside Kerala was 117; some 25 prints were released outside Kerala on November 21, 2008, including 4 prints in the United States and 11 engravings in the UAE. The film grossed a total of ₹32.6 kronor ($4.6 million). It was the highest-grossing film in Malayalam cinema until 2013. -

Mohanlal Filmography

Mohanlal filmography Mohanlal Viswanathan Nair (born May 21, 1960) is a four-time National Award-winning Indian actor, producer, singer and story writer who mainly works in Malayalam films, a part of Indian cinema. The following is a list of films in which he has played a role. 1970s [edit]1978 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes [1] 1 Thiranottam Sasi Kumar Ashok Kumar Kuttappan Released in one center. 2 Rantu Janmam Nagavally R. S. Kurup [edit]1980s [edit]1980 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Manjil Virinja Pookkal Poornima Jayaram Fazil Narendran Mohanlal portrays the antagonist [edit]1981 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Sanchari Prem Nazir, Jayan Boban Kunchacko Dr. Sekhar Antagonist 2 Thakilu Kottampuram Prem Nazir, Sukumaran Balu Kiriyath (Mohanlal) 3 Dhanya Jayan, Kunchacko Boban Fazil Mohanlal 4 Attimari Sukumaran Sasi Kumar Shan 5 Thenum Vayambum Prem Nazir Ashok Kumar Varma 6 Ahimsa Ratheesh, Mammootty I V Sasi Mohan [edit]1982 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Madrasile Mon Ravikumar Radhakrishnan Mohan Lal 2 Football Radhakrishnan (Guest Role) 3 Jambulingam Prem Nazir Sasikumar (as Mohanlal) 4 Kelkkatha Shabdam Balachandra Menon Balachandra Menon Babu 5 Padayottam Mammootty, Prem Nazir Jijo Kannan 6 Enikkum Oru Divasam Adoor Bhasi Sreekumaran Thambi (as Mohanlal) 7 Pooviriyum Pulari Mammootty, Shankar G.Premkumar (as Mohanlal) 8 Aakrosham Prem Nazir A. B. Raj Mohanachandran 9 Sree Ayyappanum Vavarum Prem Nazir Suresh Mohanlal 10 Enthino Pookkunna Pookkal Mammootty, Ratheesh Gopinath Babu Surendran 11 Sindoora Sandhyakku Mounam Ratheesh, Laxmi I V Sasi Kishor 12 Ente Mohangal Poovaninju Shankar, Menaka Bhadran Vinu 13 Njanonnu Parayatte K.