Whenuapai Airbase Social and Economic Impact Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waitakere City Council Annual Report 2008/2009

Waitakere08 City Council Annual Report Including Sustainability Reporting 20 09 08This is Waitakere City Council’s Annual Report, including the Sustainability Report 20 2 Introduction // About the Annual Report and Sustainability 09 Contents SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING ACTIVITY STATEMENTS About the City 4 City Promotion 115 From the Mayor 7 Democracy and Governance 117 Report from the Chief Executive Officer 9 Emergency Management 119 Planning and Reporting Cycle 12 West Wave Aquatic Centre 122 How the Eco City has Developed 13 Arts and Culture 124 Stakeholders 15 Cemetery 129 Sustainability Challenges 18 Leisure 132 Community Outcomes and Strategic Direction 22 Libraries 135 Parks 139 QUADRUPLE BOTTOM LINE Housing for Older Adults 143 Social 28 City Heritage 145 Cultural 34 Transport and Roads 147 Economic 38 Animal Welfare 151 Environmental 48 Vehicle Testing Station 153 Awards Received 62 Consents, Compliance and Enforcement 155 GOVERNANCE Waste Management 159 Role and Structure of Waitakere City Council 64 Stormwater 163 Council Controlled Organisations 82 Wastewater 167 Statement of Compliance and Responsibility 98 Water Supply 171 COST OF SERVICES STATEMENTS BY Support and Planning 175 STRATEGIC PLATFORM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Urban and Rural Villages 100 Income Statement 181 Integrated Transport and Communication 103 Statement of Changes in Equity 182 Strong Innovative Economy 104 Balance Sheet 183 Strong Communities 105 Statement of Cash flows 185 Active Democracy 107 Statement of Accounting Policies 187 Green Network 108 Notes to -

Spatial Land Use Strategy - North West Kumeū-Huapai, Riverhead, Redhills North

Spatial Land Use Strategy - North West Kumeū-Huapai, Riverhead, Redhills North Adopted May 2021 Strategic Land Use Framework - North West 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 4 1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................... 7 2 Background ................................................................................................................... 9 3 Strategic context.......................................................................................................... 18 4 Consultation ................................................................................................................ 20 5 Spatial Land Use Strategy for Kumeū-Huapai, Riverhead, and Redhills North ........... 23 6 Next steps ................................................................................................................... 43 Appendix 1 – Unitary Plan legend ...................................................................................... 44 Appendix 2 – Response to feedback report on the draft North West Spatial Land Use Strategy ............................................................................................................................. 46 Appendix 3 – Business land needs assessment ................................................................ 47 Appendix 4 – Constraints maps ........................................................................................ -

Historic Heritage Evaluation Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) Hobsonville Headquarters and Parade Ground (Former)

Historic Heritage Evaluation Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) Hobsonville Headquarters and Parade Ground (former) 135 and 214 Buckley Avenue, Hobsonville Figure 1: RNZAF Headquarters (5 July 2017; Auckland Council) Prepared by Auckland Council Heritage Unit July 2017 1.0 Purpose The purpose of this document is to consider the place located at 135 and 214 Buckley Road, Hobsonville against the criteria for evaluation of historic heritage in the Auckland Unitary Plan (Operative in Part) (AUP). The document has been prepared by Emma Rush, Senior Advisor Special Projects – Heritage; and Rebecca Freeman – Senior Specialist Historic Heritage, Heritage Unit, Auckland Council. It is solely for the use of Auckland Council for the purpose it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. 2.0 Identification 135 Buckley Avenue, Hobsonville (Parade Ground) and 214 Buckley Avenue, Hobsonville (former Site address Headquarters) Legal description 135 Buckley Ave - LOT 11 DP 484575 and Certificate of 214 Buckley Ave - Section 1 SO 490900 Title identifier Road reserve – Lot 15 DP 484575 NZTM grid Headquarters – Northing: 5927369; Easting: reference 1748686 Parade Ground – Northing: 5927360; Easting: 1748666 Ownership 135 Buckley Avenue – Auckland Council 214 Buckley Avenue – Auckland Council Road reserve – Auckland Transport Auckland Unitary 135 Buckley Avenue (Parade Ground) Plan zoning Open Space – Informal Recreation Zone 214 Buckley Avenue (former Headquarters) Residential - Mixed Housing Urban Zone Existing scheduled Hobsonville RNZAF -

Auckland Council District Plan (Waitakere Section)

This section updated October 2013 ACT means the Resource Management Act 1991, including amendments ACTIVE EDGE means that uses have a visual connection with the street level (usually from a ground floor) and entrances from the street. It will involve a degree of glazing but does not need to be fully glazed. The design should simply imply to users on the street that there is regular proximity and interaction between them and people within buildings. ADEQUATE FENCE (Swanson Structure Plan Area only) means a fence that, as to its nature, condition, and state of repair, is reasonably satisfactory for the purpose that it serves or is intended to serve. ADJOINING SITE(S) means the site or sites immediately abutting 1% AEP - 1% ANNUAL EXCEEDANCE PROBABLITY FLOOD LEVEL means the flood level resulting from a flood event that has an estimated probability of occurrence of 1% in any one year AIR DISCHARGE DEVICE means the point (or area) at which air and air borne pollutants are discharged from an activity excluding motor vehicles. Examples of air discharge devices Definitions include, but are not limited to a chimney, flue, fan, methods to provide evidence relating to the history roof vents, biofilters, treatment ponds, air of New Zealand conditioning unit and forced ventilation unit. ARTICULATION/ARTICULATED ALIGNMENT means vertical or horizontal elevation means the design and detailing of a wall or building facade to introduce variety, interest, a sense of AMENITY quality, and the avoidance of long blank walls. means those natural or physical qualities -

Soil Information Inventory: Patumahoe and Related Soils October 2018 Soil Information Inventory 16

Soil Information Inventory: Patumahoe and related soils October 2018 Soil Information Inventory 16 Soil Information Inventory 16: Patumahoe and related soils Compiled from published and unpublished sources by: M. Martindale (land and soil advisor, Auckland Council) D. Hicks (consulting soil scientist) P. Singleton (consulting soil scientist) Auckland Council Soil Information Inventory, SII 16 ISBN 978-1-98-858922-0 (Print) ISBN 978-1-98-858923-7 (PDF) 2 Soil information inventory 16: Patumahoe and related soils Approved for Auckland Council publication by: Name: Dr Jonathan Benge Position: Manager, Environmental Monitoring, Research and Evaluation (RIMU) Date: 1 October 2018 Recommended citation Martindale, M., D Hicks and P Singleton (2018). Soil information inventory: Patumahoe and related soils. Auckland Council soil information inventory, SII 16 © 2018 Auckland Council This publication is provided strictly subject to Auckland Council’s copyright and other intellectual property rights (if any) in the publication. Users of the publication may only access, reproduce and use the publication, in a secure digital medium or hard copy, for responsible genuine non-commercial purposes relating to personal, public service or educational purposes, provided that the publication is only ever accurately reproduced and proper attribution of its source, publication date and authorship is attached to any use or reproduction. This publication must not be used in any way for any commercial purpose without the prior written consent of Auckland Council. Auckland Council does not give any warranty whatsoever, including without limitation, as to the availability, accuracy, completeness, currency or reliability of the information or data (including third party data) made available via the publication and expressly disclaim (to the maximum extent permitted in law) all liability for any damage or loss resulting from your use of, or reliance on the publication or the information and data provided via the publication. -

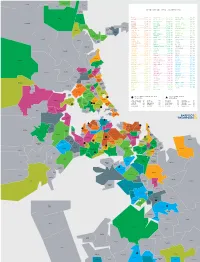

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

2009 Report Formatted

Corporate Responsibility Report 2008/09 From the Chairman This Corporate Responsibility Report is being released at a time of global economic turmoil. New Zealand is not immune from the pressures that are buffeting world markets and national economies. It is salutary to consider that the causes of our present difficulties derive in large part from unwise investments in the housing sector in the USA. It is also noteworthy that many governments around the world have put in place infrastructure investment packages designed to stimulate a rapid recovery from recession. Many of these are environmental enhancement and new housing projects. For our part, the Board of the Hobsonville Land Company is delighted that we have the final go-ahead from our Government for the Hobsonville Point development. The investment in creating a new town of 3000 houses will provide a real stimulus for the regional economy in the years ahead. This is a greenfields project, one where we start from scratch and design a new town. It is a big job and our Board has been committed from day one to applying best practice in urban design to maximise the quality of the finished product. We have a fantastic site with great natural attributes and we are determined to create a living and working environment with high amenities and a cohesive community. Our commitment to best practice includes applying modern environmental principles within the overall spending cap. We have looked carefully at stormwater management and how that can be integrated into the landscaping of the site. We are ensuring that houses are warm, comfortable and healthy by considering solar orientation and including high levels of insulation. -

North and North-West Auckland Rural Urban Boundary Project

REPORT Auckland Council Geotechnical Desk Study North and North-West Auckland Rural Urban Boundary Project Report prepared for: Auckland Council Report prepared by: Tonkin & Taylor Ltd Distribution: Auckland Council 3 copies Tonkin & Taylor Ltd (FILE) 1 copy August 2013 – Draft V2 T&T Ref: 29129.001 Table of contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 General 1 1.2 Project background 1 1.3 Scope 2 2 Site Descriptions 3 2.1 Kumeu-Whenuapai Investigation Areas 3 2.1.1 Kumeu Huapai 3 2.1.2 Red Hills and Red Hills North 3 2.1.3 Future Business 3 2.1.4 Scott Point 4 2.1.5 Greenfield Investigation Areas 4 2.1.6 Riverhead 4 2.1.7 Brigham Creek 4 2.2 Warkworth Investigation Areas 5 2.2.1 Warkworth North and East 5 2.2.2 Warkworth, Warkworth South and Future Business 5 2.2.3 Hepburn Creek 5 2.3 Silverdale Investigation Areas 6 2.3.1 Wainui East 6 2.3.2 Silverdale West and Silverdale West Business 6 2.3.3 Dairy Flat 6 2.3.4 Okura/Weiti 6 3 Geological Overview 7 3.1 Published geology 7 3.2 Geological units 9 3.2.1 General 9 3.2.2 Alluvium (Holocene) 9 3.2.3 Puketoka Formation and Undifferentiated Tauranga Group Alluvium (Pleistocene) 9 3.2.4 Waitemata Group (Miocene) 9 3.2.5 Undifferentiated Northland Allochthon (Miocene) 10 3.3 Stratigraphy 10 3.3.1 General 10 3.3.2 Kumeu-Whenuapai Investigation Area 11 3.3.3 Warkworth Investigation Area 11 3.3.4 Silverdale Investigation Area 12 3.4 Groundwater 12 3.5 Seismic Subsoil Class 13 3.5.1 Peak ground accelerations 13 4 Geotechnical Hazards 15 4.1 General 15 4.2 Hazard Potential 15 4.3 Slope Instability Potential 15 4.3.1 General 15 4.3.2 Low Slope Instability Potential 16 4.3.3 Medium Slope Instability Potential 17 4.3.4 High Slope Instability Potential 17 4.4 Liquefaction Potential 18 Geotechnical Desk Study North and North-West Auckland Rural Urban Boundary Project Job no. -

Discovering the Hindrance of Walking and Cycling in Auckland’S Urban Form

DISCOVERING THE HINDRANCE OF WALKING AND CYCLING IN AUCKLAND’S URBAN FORM. MEYER NEESON A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Urban Design at the University of Auckland, 2020. Abstract Active transport is a fundamental element in a city’s movement network that promotes a sustainable and resilient urban future, yet can only be viable in an urban setting that supports small-scale infrastructure with appropriate street environments. The 1950’s planning regimes have been dominant within Auckland’s transport development with perpetuated traditional aims of increased efficiency and high level infrastructure which enables travel in the comfort of a private vehicle. Attitudes have formulated the urban fabric through funding and investment intervention which resulted in a strong motorway network and low density, sprawling residential suburbs. Psychological public response to this environment is reflected in the heavy reliance on the private vehicle and low rates of walking and cycling. Although Auckland’s transport framework identifies the need for walking and cycling to actively form a strand of Auckland’s transport network, institutional and intellectual embedded ideas of the 1950’s prevent implementation on the ground. The failure of Auckland’s urban form was highlighted in the period of the Covid-19; post lockdown the public reverted back to old transport habits when restrictions were lifted. This pandemic put our city in the spotlight to identify its shortfalls and the urgent need to support a resilient future. Therefore, this research aims to discover the inherent infrastructure and funding barriers that hinder the growth of walking and cycling as a transport method in Auckland. -

Hobsonville Point

hobsonville point ENJOY OUR CITY. ENJOY YOUR LIFE. 12 Bernoulli Gardens by Ockham Residential showcases our continued commitment to deliver innovative, best practice housing for Aucklanders. Situated at Hobsonville Point, Auckland’s most vibrant new suburban community, Bernoulli Gardens provides a range of flexible apartment options. Our five well-appointed apartment buildings offer a lush green setting unique to Hobsonville Point. A central resident’s lounge overlooking large gardens, together with pathways and clever bump-spaces offer a real sense of community and connectedness. Bernoulli Gardens will appeal to individuals and families looking for a low maintenance, secure and social living environment. A European brick façade features elegant corner curves and contemporary detailing. These homes have a generous 2.7 metre stud, double glazing and concrete mid-floors ensuring year round comfort. A range of apartment options are available from one through to three bedrooms. Be a part of one of Auckland’s transformational urban projects. Enjoy our city. Enjoy your life. DISCLAIMER; While we have taken every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information found in this document, Ockham Residential Ltd can take no responsibility for any 3 errors or omissions. Purchasers are advised to complete their own due diligence on the subject property. DESIGN INSPIRATION Designed by Ockham Residential’s in-house architects, the inspiration for Bernoulli Gardens was simple: to encourage a sense of community by creating a relaxed, informal garden environment for residents to share. Innovative choices to remove unnecessary fences and concrete driveways have made a new suburban reality possible. A large north facing resident’s lounge opens out to generous landscaped gardens, creating bump spaces designed to foster opportunities for community and connectedness. -

Before the Auckland Unitary Plan Independent Hearings Panel

BEFORE THE AUCKLAND UNITARY PLAN INDEPENDENT HEARINGS PANEL IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 and the Local Government (Auckland Transitional Provisions) Act 2010 AND IN THE MATTER of Topic 016 RUB North/West AND IN THE MATTER of the submissions and further submissions set out in the Parties and Issues Report JOINT STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF DAVID HOOKWAY, RYAN BRADLEY AND ERYN SHIELDS ON BEHALF OF AUCKLAND COUNCIL (PLANNING – WEST AUCKLAND FRINGE) 15 OCTOBER 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 2 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 4 3. CODE OF CONDUCT .................................................................................................. 4 4. SCOPE ........................................................................................................................ 4 5. GROUP 1 – KUMEU-HUAPAI...................................................................................... 6 6. GROUP 2 - RIVERHEAD ........................................................................................... 32 7. GROUP 3 – RED HILLS OUTSIDE THE RUB / TAUPAKI ......................................... 37 8. GROUP 4 – WHENUAPAI, RED HILLS INSIDE THE RUB ........................................ 47 9. GROUP 5 – BIRDWOOD ........................................................................................... 50 10. GROUP 6 – WAITAKERE -

A History of Teal. the Origins of Air New Zealand As an International Airline

University of Canterbury L. \ (' 1_.) THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY. by IoA. THOMSON 1968 A HISTORY OF TEALe THE ORIGINS OF AIR NEW ZEALAND AS AN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINEo 1940-1967 Table of Contents Preface iii Maps and Illustrations xi Note on Abbreviations, etco xii Chapter 1: From Vision to Reality. 1 Early airline developments; Tasman pioneers; Kingsford Smith's trans-Tasman company; Empire Air Mail Scheme and its extension to New and; conferences and delays; formation of TEAL. Chapter 2: The Flying-boat Era. 50 The inaugural flight; wartime operations - military duties and commercial services; post-war changes; Sandringham flying-boats; suspension of services; Solent flying boats; route expansion; withdrawal of flying-boats. Chapter 3: From Keels to Wheels. 98 The use of landplanes over the Tasman; TEAL's chartered landplane seryice; British withdrawal from TEAL; acquisition of DC-6 landplanes; route terations; the "TEAL Deal" and the purchase of Electras; enlarged route network; the possibility of a change in role and ownership. Chapter 4: ACquisition and Expansion. 148 The reasons for, and of, New Zealand's purchase of TEAL; twenty-one years of operation; Electra troubles; TEAL's new role; DC-8 re-equipment; the negotiation of traff rights; change of name; the widening horizons of the jet age .. Chapter 5: Conclusion .. 191 International airline developments; the advantages of New Zealand ownership of an international airline; the suggested merger of Air New" Zealand and NoAoC.; contemporary developments - routes and aircraft. Appendix A 221 Appendix B 222 Bibliography 223 Preface Flying as a means of travel is no more than another s forward in man's impulsive drive to discover and explore, to colonize and trade.