A Methodology of Subject-Oriented Textual Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen Harrington Thesis

PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE BEYOND JOURNALISM: INFOTAINMENT, SATIRE AND AUSTRALIAN TELEVISION STEPHEN HARRINGTON BCI(Media&Comm), BCI(Hons)(MediaSt) Submitted April, 2009 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology, Australia 1 2 STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made. _____________________________________________ Stephen Matthew Harrington Date: 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changing relationships between television, politics, audiences and the public sphere. Premised on the notion that mediated politics is now understood “in new ways by new voices” (Jones, 2005: 4), and appropriating what McNair (2003) calls a “chaos theory” of journalism sociology, this thesis explores how two different contemporary Australian political television programs (Sunrise and The Chaser’s War on Everything) are viewed, understood, and used by audiences. In analysing these programs from textual, industry and audience perspectives, this thesis argues that journalism has been largely thought about in overly simplistic binary terms which have failed to reflect the reality of audiences’ news consumption patterns. The findings of this thesis suggest that both ‘soft’ infotainment (Sunrise) and ‘frivolous’ satire (The Chaser’s War on Everything) are used by audiences in intricate ways as sources of political information, and thus these TV programs (and those like them) should be seen as legitimate and valuable forms of public knowledge production. -

Case 3:03-Cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761

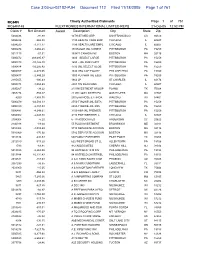

Case 3:03-cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761 MC64N Timely Authorized Claimants Page 1 of 761 MC64N148 FLEXTRONICS INTERNATIONAL LIMITED REPS 21-Oct-05 12:52 PM Claim #Net Amount Award Description City State Zip 5002436 -91.88 10TH ST MED GRP SAN FRANCISCO CA 94120 5004224 -965.80 1199 HEALTH CARE EMP CHICAGO IL 60607 5004220 -3,717.17 1199 HEALTHCARE EMPL CHICAGO IL 60607 5000476 -3,602.28 150 EAGLE JNL CORE E PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5011113 -57.51 159471 CANADA INC BOSTON MA 02116 5000472 -269,695.87 1600 - SELECT LARGE PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000473 -10,126.40 1650 - JNL FMR CAPIT PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000474 -93,205.42 1700 JNL SELECT GLOB PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5009707 -6,478.05 1838 LRG CAP EQUITY PHILADELPHIA PA 19109 5000477 -2,849.29 1900 PUTNAM JNL EQUI PITTSBURGH PA 15259 2185655 -100.43 1966 LP ST CHARLES IL 60174 5003474 -1,053.69 2001 TIN MAN FUND CHICAGO IL 60607 2095267 -38.22 210 INVESTMENT GROUP PLANO TX 75024 2057274 -755.37 22 WILLOW LIMITED PA OAK BLUFFS MA 02557 4259 -1,853.75 230 EAR NOSE & THROA WAUSAU WI 54401 5000479 -44,584.33 2750-T ROWE-JNL ESTA PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000480 -2,457.83 2850-T ROWE-JNL MID- PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000481 -4,348.61 3150-AIM-JNL PREMIER PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5004002 -2,648.80 3180 PARTNERSHIP, L. CHICAGO IL 60607 2104008 -5.20 5 - W ASSOCIATES ANDERSON SC 29622 2146318 -83.04 55 PLUS INVESTMENT BRUNSWICK ME 04011 5010968 -4,083.69 5710 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 5010969 -170.92 5782 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 1013184 -230.59 5D FAMILY PARTNERS PILET POINT TX 76258 -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

Final Costs Will Be Determined When the 2007 Plan Is Released in the Middle of the Year

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SECOND PARLIAMENT Page Wednesday, 14 March 2007 PROCEDURE ................................................................................................................................................................................... 965 Speaker’s Statement—Register of Members’ Interests ....................................................................................................... 965 PETITIONS ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 966 TABLED PAPER .............................................................................................................................................................................. 966 MINISTERIAL STATEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................... 966 Water Infrastructure .............................................................................................................................................................. 966 South East Queensland Infrastructure Plan ......................................................................................................................... 967 Gold Coast Desalination -

Record-Breaking Channel Seven Telethon Has Been Studded with Highlights That Tug on the Heart Strings and Set the Adrenaline Racing

RECORD TELETHON 2014 RAISES A STAGGERING $25,271,542 A record-breaking Channel Seven Telethon has been studded with highlights that tug on the heart strings and set the adrenaline racing. Headline performances from Perth’s The X Factor contestant Reigan Derry on the opening night and a host of Australian entertainers got big crowds at the Perth Entertainment and Convention Centre up on their feet, while the plucky Little Telethon stars, seven year-old Emily Prior and 10 year-old Patrick Majewski charmed audiences everywhere. The amazing 26 hours live-on-air weekend saw more than 300 TV production crew at work; more than 200 lights; 60 plus microphones; 55 hair and make-up artists; more than 600 entertainers; 100 Virgin Australia flights and more than 1,000 volunteers which made the Telethon weekend the most successful ever. There were plenty of major donations from the big end of town, but as always it was the generosity of the people of Western Australia that shone through the most in the huge 2014 total of $25,271,542 raised over the weekend compared to last year’s $20.7 million and brings the total raised since 1968 to $179,778,436 Prime Minister Tony Abbott committed a Federal Government donation of $1 million. Premier Colin Barnett handed over a cheque for $500,000 from the State Government on behalf of all West Australians. Party goers at The Lexus Ball raised an unbelievable $700,000 which included the sale of the Solid Gold pendant designed with the Little Telethon stars Emily and Patrick - but the weekend belonged to Emily Prior and Patrick Majewski, who stole the audiences hearts. -

Annual Report 2009

BURSWDOD PARK BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2009 WEcI*\ Mc1(U ii 'I .1W AUK' NI \VOOD 130 MU) STATEMENT OF COMPLIANCE FOR THE'EAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2009 TO THE HON TERRY WALDRON MLA MINISTER FOR RACI!IG AND GAMING In accordance with Section 61 of the Financia Maiegmiit Act 2006, we hereby thmt fr your infarmabon, and presentation In Fadiamerit, the AflflLi Rrort of th Biir'oo1 Pad Rod for th finanriat year ended 3i June 2009 The ArnuaI Fepod has been prepared in aocordnre with th prcvisionscit the Fn.rcict.I1 Mantgment Act 26 4 I Barry A Spfgeaflt Vin Nairn PRESIDENT MEMBER 31 August 2009 31 August2009 Cover: Buiswocd Park Thousands of locals and vsiors enjoy The facmties at 8urcwood Pm* andfheButswriod PeskPub4c Go?! CourseVftyenr TABLE OFCONTENTS Statement of Compliance to the Miniter Presidents RepQrt 3 General Managers Overview 4 The Year in Review Executh,e Sunimay Highlights ot 2008/2')09 5 Looking Ahead - Planning for the Future 5 Agency Profile Mission Statrneni and Borci Otactrves 6 Burswoc,d Park Board 7 Bi.rswood Park Board Operating Structure 8 Legislative Environment g A ci n rti Po rfr ryn n - P rw i4 Mmnisti'ation 10 Burswood Parks and Gidens 20 Bi.rswood Park Pubhc (3olr Course 28 RiversideFunchon Roam.Sprig Bararid C:afè 29 Golf Olubouse Leases and greenent 29 Golf Professional Shop and Operations 30 Significant Issues and Trends 32 Financial Statements Financial Statements 33 Audit Opinion 53 icey Pert ormance Indicators 55 Annual Estimates far 200W20tO 59 PRE$IDENr's REPORT MINISTER FOR RACING AND GAMING In accordance wilh Section 61 of tne F'runoaJMafiagement Acr 'uo. -

New Era of News Begins As the West Australian and Seven Perth Join Forces Under One Roof

POWER PERTH HOUSE TUESDAY, MARCH 17, 2015 SPECIAL EDITION New era of news begins as The West Australian and Seven Perth join forces under one roof A PERFECT MATCH P10 NOBODY KNOWS NEWS LIKE US P12 WINNING WEB P14 CEMENTING A NEW FUTURE P16 TELETHON TREASURES P28 Years since Fat Cat 2 44 made his TV debut 2 INSIDE The TVW evolution 4 Sporting force 8 Dynamic duo 10 Integrated news power 12 Building a future 16 Early memories 20 On the record 24 Aerial view 26 Telethon phenomenon 28 Recipe for success 30 The West Australian editor-in-chief Bob Cronin, centre, and editor Brett McCarthy oversee news conference at Newspaper House. Picture: Iain Gillespie THE WRITER Brave new media world Pam Casellas has been a professional television critic, commentator and interested There is incremental change, 800. It puts our rivals in the was a raw 19-year-old, he was Fifty years ago film took days observer of the local and the kind that moves slowly and shade and sets up an enviable offered a job in television, a to arrive by plane in Perth national television industry no one really notices the competitive advantage. matter he discussed with his before it went to air. Press for 35 years, as well as a difference. And then there is A redesigned newsroom cadet counsellor. He was advised photographers transmitted devoted consumer of countless change that is so profound that enveloping a “superdesk” thus: “Son, this TV thing is a their pictures back to the office, television hours. the old ways are gone for ever complements a highly nine-day wonder . -

The World's News Leader

Quick Facts on The World’s News Leader cnn.com/international Sara Sidner on location, Libya. What is CNN International? • CNN International is the World’s News Leader. The pioneer of 24 hour news programming CNN International remains at the forefront for delivering fast, accurate impartial news of global importance to international audiences. • With production centres in Hong Kong, London, Abu Dhabi and Atlanta, CNN Anderson Cooper on location, Sri Lanka. Anna Coren on set, Hong Kong. International is the most watched and most distributed international news channel in Asia and across the world. • CNN International is a different channel to CNN which is primarily distributed in the U.S. and covers news stories of importance to U.S. based audiences. Andrew Stevens reporting from India. Demi Moore with Anuradha Koirala What types of CNN Hero of the Year 2010. Yao Ming on Talk Asia. How does CNN programming International can I watch differ to on CNN other news International? channels? • ‘Breaking News’ is CNN International’s • Intelligence. CNN International goes trademark. Every day, CNN reports on beyond the headlines: analysing the latest international stories, the facts; providing context; so our business news and sports highlights. viewers understand how and why a Piers Morgan Tonight with Oprah Winfrey. story is relevant to their everyday lives. • CNN International also produces a wealth of news documentary and • Diversity. The strength and diversity feature programming including of CNN International’s newsgathering the travel programme ‘CNNGo’; resources enables CNN International environmental themed show ‘Eco journalists to report from the frontlines, Solutions’ and the ‘CNN Freedom on multiple stories across different Project’ weekly specials and continents at the same time, giving our documentaries, designed to help fight viewers the inside perspectives. -

The Aibs 2020

#theAIBs Programme EVENT PARTNER SPONSOR Programme The AIBs 2020 Awards production Executive Producer Simon Spanswick Producer Clare Dance Editorial Director Gunda Cannon Programme Director Neil Stainsby Studio Director Rob Rowse Network Operations Robbie McKendrick London Camera Peter Lloyd-Williams Video Editor Ben German Design Tony de Simone Photography Rukaya César The team at Church House Westminster 3 The AIBs 2020 Host Host As an anchor she leverages her field experience to ask the hard questions, with the grasp that comes from having had on the ground presence. Kim has anchored major events ranging from; the inauguration and impeachment hearing of US President Donald Trump to the death of Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi on the other side of the globe. She also frequently hosts Al Jazeera’s flagship shows “Inside Story” and “Newshour”; and has played a pivotal role in the Network’s coverage of the coronavirus pandemic and the black lives matter protests. Kim Vinnell is a presenter for Al Jazeera English. She believes brave journalism She has previously anchored for TRT World is needed now more than ever, and has in Turkey, was a freelance correspondent committed her career to putting truth to covering East Africa from Tanzania, and was power and to conveying untold stories. a senior correspondent for TVNZ and TV3 in New Zealand. As an international correspondent she has covered some of the major news stories of She is a proud kiwi with Maori heritage, of the last decade; including the war in Syria and Ngāti Toa and Ngati Raukawa descent. She Eastern Ukraine, Iraq’s fight against ISIS, the prides herself on being a fierce global political fallout from the 2014 war in Gaza advocate for gender equality and and the Mediterranean migrant crisis. -

35Th Annual NEWS & DDOCUMENTARYOCUMENTARY EEMMYMMY® AAWARDSWARDS

335th5th AnnualAnnual TTuesday,uesday, SSeptembereptember 330,0, 22014014 JJazzazz aatt LLincolnincoln CCenter‘senter‘s FFrederickrederick PP.. RRoseose HHallall News & Doc Emmys 2014 program.indd 1 9/18/14 7:09 PM News & Doc Emmys 2014 program.indd 2 9/18/14 7:09 PM 35th Annual NEWS & DDOCUMENTARYOCUMENTARY EEMMYMMY® AAWARDSWARDS LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN CONTENTS Welcome to the 35th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards! As 3 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN the new Chairman of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, it 4 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT is my pleasure to join you at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall WILLIAM J. SMALL to celebrate the hard work and dedication to craft that we honor tonight. 5 A Force for Journalistic Excellence Much has been written in the consumer and professional press of the in the Glory Days of TV News changes occurring in our industry, the television industry. These well docu- by Elizabeth Jensen mented changes are tectonic: the diversity of new channels continues; the new business models for funding and paying for content are multiplying; the mobile platforms 8 Mr. Small by Bob Schieffer that free the consumer to watch anytime and anywhere are appearing not only in the palm of our hands, but now, even on our wrist watches! 8 Bill the Great This is an exciting time and the journalists and documentarians we pay tribute to this evening by Lesley Stahl are on the front line of these changes. They are our eyes and ears across the globe, bringing back the The Godfather stories that affect each and every one of us. -

Another Liberal Intervention Party Rules ANU Liberal Club AGM Invalid and Requests Resignation of 2007 President

Student cargo P3 Light show P11 Folk Festival P11 Earth Hour P13 Nowhere bound P16 The Australian National University Student Newspaper | 1948 - 2008 10 April - 7 May 2008 Another Liberal Intervention Party rules ANU Liberal Club AGM invalid and requests resignation of 2007 President Robert Wiblin Editor Serious allegations have been raised about the conduct of last year’s ANU Liberal Club Presi- dent, Aaron McDonnell, who it is claimed changed the club’s constitution to make it more dif- ficult to expel members - without ever bringing those changes to a club meeting. While the charges have not been proven it threat- ens to put a cloud over a possible political career. The issue began when some vigilant members no- ticed that varying versions of the Club’s constitution were sent out to members and used to affiliate with ANUSA through 2007/08, all purporting to be correct as of an April 7th 2006 Special Gen- eral Meeting. It was clear that the changes could have been Duped? Members of the ANU Liberal Club look on as Tony Abbott MP speaks at ‘Politics at the Pub’ during O-Week Tully Fletcher advantageous to McDonnell, as group of alienated members “conspiracy” but rather just an investigate the matter to ensure the confusion was more than the he had reason to fear expulsion impotently attempting to pro- “administrative error” and fur- that no doubts would linger on output of a lively ‘fantasy club by factional enemies within the voke an upset in club elections. ther discussion was shut down and damage the club’s credibility. -

2017 Annual Report Muscular Dystrophy Wa Is a Small Organisation Making a Big Impact

2017 ANNUAL REPORT MUSCULAR DYSTROPHY WA IS A SMALL ORGANISATION MAKING A BIG IMPACT. WE ARE PASSIONATE ABOUT IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF LIFE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH NEUROMUSCULAR CONDITIONS. WE WORK WITH HUNDREDS OF FAMILIES, HELPING THEM GET THE BEST SUPPORT AND SERVICES THEY NEED AND CONNECTING THEM TO OTHERS WITH SIMILAR CONDITIONS, ENABLING THEM TO LEAD FULL LIVES. 50 years is a fine achievement and one that deserves celebrating. While I am incredibly proud to see Muscular Dystrophy WA reach this wonderful milestone, what is most remarkable to me is the lasting impact this important organisation has on the muscular dystrophy community. In 2017, my family and I had the opportunity to attend all three 50th Anniversary events. What became very apparent was the overwhelming sense of friendship, spirit and community – everyone was gathered together for the same reason – all connected by muscular dystrophy and all willing to make a difference, truly embodying Muscular Dystrophy WA’s belief that together we are better. I am truly privileged to have been the Patron for the past 30 years to such a passionate organisation that aims to improve the quality of life and wellbeing for those living with muscular dystrophy and their families. I thank Muscular Dystrophy WA for awarding me Honorary Life Membership in 2017 - it is an honour to assist you. MESSAGE Muscular Dystrophy WA continues to provide benefit to their community; be it through research or through practical support to improve their quality of life. I am so pleased to see the organisation FROM THE reaching and impacting more people with neuromuscular conditions than ever before.