Social CRM in Higher Education Introduction Many Colleges And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| Google+ for Business How Googles Social Network Changes

GOOGLE+ FOR BUSINESS HOW GOOGLES SOCIAL NETWORK CHANGES EVERYTHING 2ND EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Chris Brogan | 9780789750068 | | | | | Google Maps is the new social network Here's a quick recap of Google's social media moves in February 8 : The Wall Street Journal reports Google prepared to unveil a Google+ for Business How Googles Social Network Changes Everything 2nd edition component to Gmail that would display a stream of "media and status updates" within the web interface. More Insider Sign Out. Google then goes out and gathers relevant content from all over the Web. Facebook vs. July 15, The Internet is a great tool for job hunting, but it Google+ for Business How Googles Social Network Changes Everything 2nd edition also made competing for a job much more challenging. Location-based services: Are they there yet? June Digg co-founder Kevin Rose posts a tweet that a "very credible" source said Google would be launching a Facebook competitor, called Google Me "very soon. Because each of these tools operates differently and has its own set of goals, the specific tactics will vary greatly for each of the sites. Although there isn't any word on specific product details David Glazer, engineering director at Google confirms the company will invest more effort to make its services more "socially aware" in a recent blog post. My next post will examine some of the strategies and tactics that can be used to generate new business from each of these social networking tools. The purchase rehashed speculation that the search giant is interested in working its way into social media, possibly with a game-centered service called "Google Me. -

Obtaining and Using Evidence from Social Networking Sites

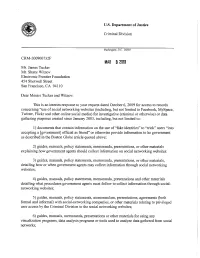

U.S. Department of Justice Criminal Division Washington, D.C. 20530 CRM-200900732F MAR 3 2010 Mr. James Tucker Mr. Shane Witnov Electronic Frontier Foundation 454 Shotwell Street San Francisco, CA 94110 Dear Messrs Tucker and Witnov: This is an interim response to your request dated October 6, 2009 for access to records concerning "use of social networking websites (including, but not limited to Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, Flickr and other online social media) for investigative (criminal or otherwise) or data gathering purposes created since January 2003, including, but not limited to: 1) documents that contain information on the use of "fake identities" to "trick" users "into accepting a [government] official as friend" or otherwise provide information to he government as described in the Boston Globe article quoted above; 2) guides, manuals, policy statements, memoranda, presentations, or other materials explaining how government agents should collect information on social networking websites: 3) guides, manuals, policy statements, memoranda, presentations, or other materials, detailing how or when government agents may collect information through social networking websites; 4) guides, manuals, policy statements, memoranda, presentations and other materials detailing what procedures government agents must follow to collect information through social- networking websites; 5) guides, manuals, policy statements, memorandum, presentations, agreements (both formal and informal) with social-networking companies, or other materials relating to privileged user access by the Criminal Division to the social networking websites; 6) guides, manuals, memoranda, presentations or other materials for using any visualization programs, data analysis programs or tools used to analyze data gathered from social networks; 7) contracts, requests for proposals, or purchase orders for any visualization programs, data analysis programs or tools used to analyze data gathered from social networks. -

Chazen Society Fellow Interest Paper Orkut V. Facebook: the Battle for Brazil

Chazen Society Fellow Interest Paper Orkut v. Facebook: The Battle for Brazil LAUREN FRASCA MBA ’10 When it comes to stereotypes about Brazilians – that they are a fun-loving people who love to dance samba, wear tiny bathing suits, and raise their pro soccer players to the levels of demi-gods – only one, the idea that they hold human connection in high esteem, seems to be born out by concrete data. Brazilians are among the savviest social networkers in the world, by almost all engagement measures. Nearly 80 percent of Internet users in Brazil (a group itself expected to grow by almost 50 percent over the next three years1) are engaged in social networking – a global high. And these users are highly active, logging an average of 6.3 hours on social networks and 1,220 page views per month per Internet user – a rate second only to Russia, and almost double the worldwide average of 3.7 hours.2 It is precisely this broad, highly engaged audience that makes Brazil the hotly contested ground it is today, with the dominant social networking Web site, Google’s Orkut, facing stiff competition from Facebook, the leading aggregate Web site worldwide. Social Network Services Though social networking Web sites would appear to be tools born of the 21st century, they have existed since even the earliest days of Internet-enabled home computing. Starting with bulletin board services in the early 1980s (accessed over a phone line with a modem), users and creators of these Web sites grew increasingly sophisticated, launching communities such as The WELL (1985), Geocities (1994), and Tripod (1995). -

International Students' Use of Social Network Sites For

INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS’ USE OF SOCIAL NETWORK SITES FOR COLLEGE CHOICE ACTIVITIES AND DECISION MAKING Natalia Rekhter Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education Indiana University June 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Dissertation Committee _______________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson, Robin Hughes, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________ Committee Member, Donald Hossler, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________ Committee Member, Gary Pike, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________ Committee Member, James Scheurich, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________ Committee Member, Eric Wright, Ph.D. Date of Defense March 9, 2017 ii I dedicate this dissertation to my husband, Mark Rekhter, M.D., Ph.D. Thank you for always encouraging me to persist, believing in me, listening to my endless self-doubts, always finding words of reassurance, and for being by my side all the way. I also dedicate this dissertation to my sons Ilya and Misha, who inspired me by their own successes, intelligence, and dedication. iii Acknowledgements I was able to complete this dissertation research only because of the encouragement, guidance, support and care of my dissertation research advisor Dr. Donald Hossler. Dr. Hossler, thank you for your infinite patience, for challenging my views, for always inspiring me to do better and reach higher, for your suggestions, your guidance, your feedback and your trust in me. An opportunity to work with you and learn from you made a profound impact on me as a person and as a researcher. -

Social Networking: a Guide to Strengthening Civil Society Through Social Media

Social Networking: A Guide to Strengthening Civil Society Through Social Media DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Counterpart International would like to acknowledge and thank all who were involved in the creation of Social Networking: A Guide to Strengthening Civil Society through Social Media. This guide is a result of collaboration and input from a great team and group of advisors. Our deepest appreciation to Tina Yesayan, primary author of the guide; and Kulsoom Rizvi, who created a dynamic visual layout. Alex Sardar and Ray Short provided guidance and sound technical expertise, for which we’re grateful. The Civil Society and Media Team at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was the ideal partner in the process of co-creating this guide, which benefited immensely from that team’s insights and thoughtful contributions. The case studies in the annexes of this guide speak to the capacity and vision of the featured civil society organizations and their leaders, whose work and commitment is inspiring. This guide was produced with funding under the Global Civil Society Leader with Associates Award, a Cooperative Agreement funded by USAID for the implementation of civil society, media development and program design and learning activities around the world. Counterpart International’s mission is to partner with local organizations - formal and informal - to build inclusive, sustainable communities in which their people thrive. We hope this manual will be an essential tool for civil society organizations to more effectively and purposefully pursue their missions in service of their communities. -

Jon Leibowitz, Chairman J. Thomas Rosch Edith Ramirez Julie Brill

102 3136 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS: Jon Leibowitz, Chairman J. Thomas Rosch Edith Ramirez Julie Brill ____________________________________ ) In the Matter of ) ) GOOGLE INC., ) a corporation. ) DOCKET NO. C-4336 ____________________________________) COMPLAINT The Federal Trade Commission, having reason to believe that Google Inc. (“Google” or “respondent”), a corporation, has violated the Federal Trade Commission Act (“FTC Act”), and it appearing to the Commission that this proceeding is in the public interest, alleges: 1. Respondent Google is a Delaware corporation with its principal office or place of business at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043. 2. The acts and practices of respondent as alleged in this complaint have been in or affecting commerce, as “commerce” is defined in Section 4 of the FTC Act. RESPONDENT’S BUSINESS PRACTICES 3. Google is a technology company best known for its web-based search engine, which provides free search results to consumers. Google also provides various free web products to consumers, including its widely used web-based email service, Gmail, which has been available since April 2004. Among other things, Gmail allows consumers to send and receive emails, chat with other users through Google’s instant messaging service, Google Chat, and store email messages, contact lists, and other information on Google’s servers. 4. Google’s free web products for consumers also include: Google Reader, which allows users to subscribe to, read, and share content online; Picasa, which allows users to edit, post, and share digital photos; and Blogger, Google’s weblog publishing tool that allows users to share text, photos, and video. -

EPIC FTC Google Purchase Tracking Complaint

Before the Federal Trade Commission Washington, DC In the Matter of ) ) Google Inc. ) ) ___________________________________) Complaint, Request for Investigation, Injunction, and Other Relief Submitted by The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) I. Introduction 1. This complaint concerns “Store Sales Measurement,” a consumer profiling technique pursued by the world’s largest Internet company to track consumers who make offline purchases. Google has collected billions of credit card transactions, containing personal customer information, from credit card companies, data brokers, and others and has linked those records with the activities of Internet users, including product searches and location searches. This data reveals sensitive information about consumer purchases, health, and private lives. According to Google, it can track about 70% of credit and debit card transactions in the United States. 2. Google claims that it can preserve consumer privacy while correlating advertising impressions with store purchases, but Google refuses to reveal—or allow independent testing of— the technique that would make this possible. The privacy of millions of consumers thus depends on a secret, proprietary algorithm. And although Google claims that consumers can opt out of being tracked, the process is burdensome, opaque, and misleading. 3. Google’s reliance on a secret, proprietary algorithm for assurances of consumer privacy, Google’s collection of massive numbers of credit card records through unidentified “third-party partnerships,” and Google’s use of an opaque and misleading “opt-out” mechanism are unfair and deceptive trade practices subject to investigation and injunction by the FTC. II. Parties 4. The Electronic Privacy Information Center (“EPIC”) is a public interest research center located in Washington, D.C. -

Recommendations for Businesses and Policymakers Ftc Report March 2012

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BUSINESSES AND POLICYMAKERS FTC REPORT FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION | MARCH 2012 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR BUSINESSES AND POLICYMAKERS FTC REPORT MARCH 2012 CONTENTS Executive Summary . i Final FTC Privacy Framework and Implementation Recommendations . vii I . Introduction . 1 II . Background . 2 A. FTC Roundtables and Preliminary Staff Report .......................................2 B. Department of Commerce Privacy Initiatives .........................................3 C. Legislative Proposals and Efforts by Stakeholders ......................................4 1. Do Not Track ..............................................................4 2. Other Privacy Initiatives ......................................................5 III . Main Themes From Commenters . 7 A. Articulation of Privacy Harms ....................................................7 B. Global Interoperability ..........................................................9 C. Legislation to Augment Self-Regulatory Efforts ......................................11 IV . Privacy Framework . 15 A. Scope ......................................................................15 1. Companies Should Comply with the Framework Unless They Handle Only Limited Amounts of Non-Sensitive Data that is Not Shared with Third Parties. .................15 2. The Framework Sets Forth Best Practices and Can Work in Tandem with Existing Privacy and Security Statutes. .................................................16 3. The Framework Applies to Offline As Well As Online Data. .........................17 -

Re-Socializing Online Social Networks

Re-Socializing Online Social Networks Michael D¨urr1 and Martin Werner1 Mobile and Distributed Systems Group Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, Germany {michael.duerr,martin.werner}@ifi.lmu.de, Web: http://www.mobile.ifi.lmu.de/ Abstract. Recently the rapid development of Online Social Networks (OSN) has extreme influenced our global community's communication patterns. This primarily manifests in an exponentially increasing number of users of Social Network Services (SNS) such as Facebook or Twitter. A fundamental problem accompanied by the utilization of OSNs is given by an insufficient guarantee for its users informational self-determination and an intolerable dissemination of socially incompatible content. This reflects in severe shortcomings for both the possibility to customize pri- vacy and security settings and the unsolicited centralized data acquisition and aggregation of profile information and content. Considering these problems, we provide an analysis of requirements an OSN has to fulfill in order to guarantee compliance with its users' privacy demands. Furthermore, we present a novel decentralized multi-domain OSN design which complies with our requirements. This work signifi- cantly differs from existing approaches in that it, for the first time, allows for a technically mature mapping of real-life communication patterns to an OSN. Our concept forms the basis for a secure and privacy-enhanced OSN architecture which eliminates the problem of socially incompatible content dissemination. Key words: Availability, Informational Self-Determination, Online So- cial Networks, Privacy, Trust 1 Introduction Online Social Networks (OSN) represent a means to map communication flows of real-life relationships to existing computer networks such as the Internet. Al- most all successful Social Network Service (SNS) providers like LinkedIn, Xing, MySpace, Facebook, Google Buzz, YouTube, Twitter, and others, operate their services commercially and in a centralized way. -

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 30 Nov 2010 15:03:55 UTC Contents Articles Google 1 Criticism of Google 20 AdWords 33 AdSense 39 List of Google products 44 Blogger (service) 60 Google Earth 64 YouTube 85 Web search engine 99 User:Moonglum/ITEC30011 105 References Article Sources and Contributors 106 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 112 Article Licenses License 114 Google 1 Google [1] [2] Type Public (NASDAQ: GOOG , FWB: GGQ1 ) Industry Internet, Computer software [3] [4] Founded Menlo Park, California (September 4, 1998) Founder(s) Sergey M. Brin Lawrence E. Page Headquarters 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Eric E. Schmidt (Chairman & CEO) Sergey M. Brin (Technology President) Lawrence E. Page (Products President) Products See list of Google products. [5] [6] Revenue US$23.651 billion (2009) [5] [6] Operating income US$8.312 billion (2009) [5] [6] Profit US$6.520 billion (2009) [5] [6] Total assets US$40.497 billion (2009) [6] Total equity US$36.004 billion (2009) [7] Employees 23,331 (2010) Subsidiaries YouTube, DoubleClick, On2 Technologies, GrandCentral, Picnik, Aardvark, AdMob [8] Website Google.com Google Inc. is a multinational public corporation invested in Internet search, cloud computing, and advertising technologies. Google hosts and develops a number of Internet-based services and products,[9] and generates profit primarily from advertising through its AdWords program.[5] [10] The company was founded by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, often dubbed the "Google Guys",[11] [12] [13] while the two were attending Stanford University as Ph.D. -

Download Download

International Journal of Management & Information Systems – First Quarter 2011 Volume 15, Number 1 The Security Implications Of Ubiquitous Social Media Chris Rose, Walden University, USA ABSTRACT Social media web sites allow users to share information, communicate with each other, network and interact but because of the easy transfer of information between different social media sites, information that should be private becomes public and opens the users to serious security risks. In addition, there is also massive over-sharing of information by the users of these sites, and if this is combined with the increased availability of location-based information, then all this can be aggregated causing an unacceptable risks and unintended consequences for users. INTRODUCTION he dot-com bubble in 2001 was an economic disaster and marked a turning point for the Internet. At that time many pundits claimed that the importance of the Internet as a vehicle for commerce was T overstated, however, in many of these instances a collapse was just a result of evolving technologies and the rise of Web 2.0. "The concept of "Web 2.0" began with a conference brainstorming session between O'Reilly and MediaLive International. Dale Dougherty, web pioneer and O'Reilly VP, noted that far from having "crashed", the web was more important than ever, with exciting new applications and sites popping up with surprising regularity" (O"Reilly, 2005). At the Open Government and Innovations Conference in Washington in 2009, speakers noted that people talk about Web 2.0 as if it is a fully evolved media when in fact it is not. -

Collaborative Filtering for Orkut Communities: Discovery of User Latent Behavior

Collaborative Filtering for Orkut Communities: Discovery of User Latent Behavior Wen-Yen Chen∗ Jon-Chyuan Chu∗ Junyi Luan∗ University of California MIT Peking University Santa Barbara, CA 93106 Cambridge, MA 02139 Beijing 100084, China [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Hongjie Bai Yi Wang Edward Y. Chang Google Research Google Research Google Research Beijing 100084, China Beijing 100084, China Beijing 100084, China [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT General Terms Users of social networking services can connect with each Algorithms, Experimentation other by forming communities for online interaction. Yet as the number of communities hosted by such websites grows Keywords over time, users have even greater need for effective commu- nity recommendations in order to meet more users. In this Recommender systems, collaborative filtering, association paper, we investigate two algorithms from very different do- rule mining, latent topic models, data mining mains and evaluate their effectiveness for personalized com- munity recommendation. First is association rule mining 1. INTRODUCTION (ARM), which discovers associations between sets of com- munities that are shared across many users. Second is latent Much information is readily accessible online, yet we as Dirichlet allocation (LDA), which models user-community humans have no means of processing all of it. To help users co-occurrences using latent aspects. In comparing LDA with overcome the information overload problem and sift through ARM, we are interested in discovering whether modeling huge amounts of information efficiently, recommender sys- low-rank latent structure is more effective for recommen- tems have been developed to generate suggestions based on dations than directly mining rules from the observed data.