International Students' Use of Social Network Sites For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Universidad De Alicante Facultad De Ciencias Económicas Y Empresariales

UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ECONÓMICAS Y EMPRESARIALES GRADO EN PUBLICIDAD Y RELACIONES PÚBLICAS CURSO ACADÉMICO 2019 - 2020 EL FUTURO CRECIMIENTO DE LAS REDES SOCIALES: INSTAGRAM, FACEBOOK Y TIKTOK LAURA PALAO PEDRÓS VICENTA BAEZA DEVESA DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICACIÓN Y PSICOLOGÍA SOCIAL Alicante, mayo de 2020 RESUMEN En un entorno cambiante como la publicidad es vital adelantarse a los nuevos escenarios. Cada vez son más las empresas que invierten en marketing digital y en redes sociales. El objetivo del presente trabajo es hacer una previsión sobre el futuro crecimiento de las redes sociales Instagram, Facebook y TikTok, centrándose en esta última. La finalidad es analizar el rápido crecimiento de TikTok, averiguar qué factores han propiciado dicho crecimiento y cómo va a afectar al resto de plataformas. Para ello realiza un análisis DAFO con el fin de conocer los puntos fuertes y débiles de cada aplicación y un estudio sobre los testimonios de usuarios y expertos en TikTok. De este modo se demuestra la repercusión que va a tener esta aplicación en el sector publicitario ya que va a ser la preferida por las marcas en el futuro. Palabras clave: redes sociales, Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, publicidad. 2 ÍNDICE Resumen …………………….………………….………………………………….....……….2 1. Introducción ………………………………………………………...…………..…………..6 2. Estado de la cuestión y/o marco teórico ………………………………………….…….…..7 2.1. ¿Qué son las redes sociales? …………………………………………………………...7 2.2. Historia y características de las redes sociales más recientes ………………………..10 -

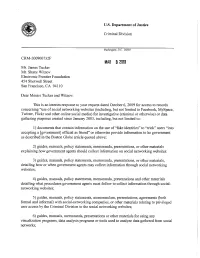

Obtaining and Using Evidence from Social Networking Sites

U.S. Department of Justice Criminal Division Washington, D.C. 20530 CRM-200900732F MAR 3 2010 Mr. James Tucker Mr. Shane Witnov Electronic Frontier Foundation 454 Shotwell Street San Francisco, CA 94110 Dear Messrs Tucker and Witnov: This is an interim response to your request dated October 6, 2009 for access to records concerning "use of social networking websites (including, but not limited to Facebook, MySpace, Twitter, Flickr and other online social media) for investigative (criminal or otherwise) or data gathering purposes created since January 2003, including, but not limited to: 1) documents that contain information on the use of "fake identities" to "trick" users "into accepting a [government] official as friend" or otherwise provide information to he government as described in the Boston Globe article quoted above; 2) guides, manuals, policy statements, memoranda, presentations, or other materials explaining how government agents should collect information on social networking websites: 3) guides, manuals, policy statements, memoranda, presentations, or other materials, detailing how or when government agents may collect information through social networking websites; 4) guides, manuals, policy statements, memoranda, presentations and other materials detailing what procedures government agents must follow to collect information through social- networking websites; 5) guides, manuals, policy statements, memorandum, presentations, agreements (both formal and informal) with social-networking companies, or other materials relating to privileged user access by the Criminal Division to the social networking websites; 6) guides, manuals, memoranda, presentations or other materials for using any visualization programs, data analysis programs or tools used to analyze data gathered from social networks; 7) contracts, requests for proposals, or purchase orders for any visualization programs, data analysis programs or tools used to analyze data gathered from social networks. -

Introduction to Web 2.0 Technologies

Introduction to Web 2.0 Joshua Stern, Ph.D. Introduction to Web 2.0 Technologies What is Web 2.0? Æ A simple explanation of Web 2.0 (3 minute video): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0LzQIUANnHc&feature=related Æ A complex explanation of Web 2.0 (5 minute video): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsa5ZTRJQ5w&feature=related Æ An interesting, fast-paced video about Web.2.0 (4:30 minute video): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLlGopyXT_g Web 2.0 is a term that describes the changing trends in the use of World Wide Web technology and Web design that aim to enhance creativity, secure information sharing, increase collaboration, and improve the functionality of the Web as we know it (Web 1.0). These have led to the development and evolution of Web-based communities and hosted services, such as social-networking sites (i.e. Facebook, MySpace), video sharing sites (i.e. YouTube), wikis, blogs, etc. Although the term suggests a new version of the World Wide Web, it does not refer to any actual change in technical specifications, but rather to changes in the ways software developers and end- users utilize the Web. Web 2.0 is a catch-all term used to describe a variety of developments on the Web and a perceived shift in the way it is used. This shift can be characterized as the evolution of Web use from passive consumption of content to more active participation, creation and sharing. Web 2.0 Websites allow users to do more than just retrieve information. -

Bbvaopenmind.Com 19 Key Essays on How Internet Is Changing Our Lives

bbvaopenmind.com 19 Key Essays on How Internet Is Changing Our Lives CH@NGE Zaryn Dentzel How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life bbvaopenmind.com How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Zaryn Dentzel CEO, Tuenti bbvaopenmind.com How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life Society, Community, Individuals Zaryn Dentzel 5 Zaryn Dentzel es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zaryn_Dentzel Illustration Catell Ronca bbvaopenmind.com 7 Zaryn Dentzel Zaryn Dentzel is the founder and CEO of Tuenti, a Spanish tech company centered on mobile communications whose multi-platform integrates the best of instant messaging and the most private and secure social network. Also a member of the cabinet of advisors to Crown Prince Felipe for the Principe de Girona Foundation, Dentzel is involved in promoting education and entrepreneurship among young people in Spain. He studied at UC Santa Barbara and Occidental College, graduating with a degree in Spanish Literature, and Diplomacy and World Affairs. How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life Sites and services that have changed my life tuenti.com techcrunch.com spotify.com Kinect Training bbvaopenmind.com Society, Community, Individuals bbvaopenmind.com 9 How the Internet Has Changed Everyday Life What Happened? The Internet has turned our existence upside down. It has revolutionized communications, to the extent that it is now our preferred medium of ev- Zaryn Dentzel eryday communication. In almost everything we do, we use the Internet. Ordering a pizza, buying a television, sharing a moment with a friend, send- ing a picture over instant messaging. Before the Internet, if you wanted to keep up with the news, you had to walk down to the newsstand when it opened in the morning and buy a local edition reporting what had happened the previous day. -

Chazen Society Fellow Interest Paper Orkut V. Facebook: the Battle for Brazil

Chazen Society Fellow Interest Paper Orkut v. Facebook: The Battle for Brazil LAUREN FRASCA MBA ’10 When it comes to stereotypes about Brazilians – that they are a fun-loving people who love to dance samba, wear tiny bathing suits, and raise their pro soccer players to the levels of demi-gods – only one, the idea that they hold human connection in high esteem, seems to be born out by concrete data. Brazilians are among the savviest social networkers in the world, by almost all engagement measures. Nearly 80 percent of Internet users in Brazil (a group itself expected to grow by almost 50 percent over the next three years1) are engaged in social networking – a global high. And these users are highly active, logging an average of 6.3 hours on social networks and 1,220 page views per month per Internet user – a rate second only to Russia, and almost double the worldwide average of 3.7 hours.2 It is precisely this broad, highly engaged audience that makes Brazil the hotly contested ground it is today, with the dominant social networking Web site, Google’s Orkut, facing stiff competition from Facebook, the leading aggregate Web site worldwide. Social Network Services Though social networking Web sites would appear to be tools born of the 21st century, they have existed since even the earliest days of Internet-enabled home computing. Starting with bulletin board services in the early 1980s (accessed over a phone line with a modem), users and creators of these Web sites grew increasingly sophisticated, launching communities such as The WELL (1985), Geocities (1994), and Tripod (1995). -

The Complete Guide to Social Media from the Social Media Guys

The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Nov 2010 19:01:07 UTC Contents Articles Social media 1 Social web 6 Social media measurement 8 Social media marketing 9 Social media optimization 11 Social network service 12 Digg 24 Facebook 33 LinkedIn 48 MySpace 52 Newsvine 70 Reddit 74 StumbleUpon 80 Twitter 84 YouTube 98 XING 112 References Article Sources and Contributors 115 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 125 Social media 1 Social media Social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable publishing techniques. Social media uses web-based technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein define social media as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, which allows the creation and exchange of user-generated content."[1] Businesses also refer to social media as consumer-generated media (CGM). Social media utilization is believed to be a driving force in defining the current time period as the Attention Age. A common thread running through all definitions of social media is a blending of technology and social interaction for the co-creation of value. Distinction from industrial media People gain information, education, news, etc., by electronic media and print media. Social media are distinct from industrial or traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and film. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible to enable anyone (even private individuals) to publish or access information, compared to industrial media, which generally require significant resources to publish information. -

Opportunities and Threats for Press Freedom and Democratization CONFERENCE REPORT

IMS Conference on ICTs and networked communications environments Opportunities and threats for press freedom and democratization CONFERENCE REPORT Copenhagen 15–16 September 2008 Hosted by International Media Support With support from: Open Society Institute · Nokia · Telia Contents Foreword............................................................ 5 1 Introduction ................................................ 4 2 Day one – the EXPO .................................... 7 3 Day two – the debates ............................... 9 3.1 The framework: the legal and technical aspects ...........................12 3.2 The content: media diversity and citizen journalism .....................15 3.3 The context: freedom of expression and the democratic potential ................................................................17 4 Concluding remarks .................................. 21 5 Annexes – user guides .............................. 26 5.1 Annex 1: How to make a blog on blogger.com .............................26 52. Annex 2: What is Jaiku? ..................................................................30 5.3 Annex 3: Bambuser .........................................................................35 Opportunities and threats for press freedom and democratization 3 4 International Media Support Foreword Foreword Global means of communication are undergoing significant changes. This is a consequence of the emergence of networked communications environment, supported by inter-connected and converging internet-based technologies, greatly -

Migración De Los Jóvenes Españoles En Redes Sociales, De Tuenti a Facebook Y De Facebook a Instagram

Migración de los jóvenes españoles en redes sociales... | 48 Migración de los jóvenes españoles en redes sociales, de Tuenti a Facebook y de Facebook a Instagram. La segunda migración Spanish youth and teenagers migrating through social networks. From Tuenti to Facebook and from Facebook to Instagram. The second migration Georgina Victoria Marcelino Mercedes Investigadora sobre gestión cultural y comunicación en medios digitales en el programa de Doctorado en Publicidad y Relaciones Públicas (Universidad Camilo José Cela) Fecha de recepción: 25 de marzo de 2015 Fecha de revisión: 21 de junio de 2015 Para citar este artículo: Marcelino Mercedes, G. V. (2015): Migración de los jóvenes españoles en redes sociales, de Tuenti a Facebook y de Facebook a Instagram. La segunda migración, Icono 14, volumen (13), pp. 48-72. doi: 10.7195/ri14.v13i2.821 DOI: ri14.v13i2.821 | ISSN: 1697-8293 | Año 2015 Volumen 13 Nº 2 | ICONO14 49 | Georgina Victoria Marcelino Mercedes Resumen Los Nativos digitales conviven de manera natural con las nuevas tecnologías y los fenómenos sociales que originan. Constituyen una comunidad virtual flexible y a la vez exigente, demandando redes sociales que presenten contenidos y usos adaptados a su personalidad e intereses, por ello, cuando consideran que una red deja de suplir sus necesidades de interacción, la abandonan. En España se ha suscitado uno de los casos más interesantes de movimiento de usuarios de redes sociales: jóvenes y adolescentes españoles mantuvieron durante algunos años una frecuencia de participación notable en la red social Tuenti, abandonándola progresivamente al trasladarse hacia Facebook, una red similar con notable carácter internacional. -

Social Networking: a Guide to Strengthening Civil Society Through Social Media

Social Networking: A Guide to Strengthening Civil Society Through Social Media DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Counterpart International would like to acknowledge and thank all who were involved in the creation of Social Networking: A Guide to Strengthening Civil Society through Social Media. This guide is a result of collaboration and input from a great team and group of advisors. Our deepest appreciation to Tina Yesayan, primary author of the guide; and Kulsoom Rizvi, who created a dynamic visual layout. Alex Sardar and Ray Short provided guidance and sound technical expertise, for which we’re grateful. The Civil Society and Media Team at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was the ideal partner in the process of co-creating this guide, which benefited immensely from that team’s insights and thoughtful contributions. The case studies in the annexes of this guide speak to the capacity and vision of the featured civil society organizations and their leaders, whose work and commitment is inspiring. This guide was produced with funding under the Global Civil Society Leader with Associates Award, a Cooperative Agreement funded by USAID for the implementation of civil society, media development and program design and learning activities around the world. Counterpart International’s mission is to partner with local organizations - formal and informal - to build inclusive, sustainable communities in which their people thrive. We hope this manual will be an essential tool for civil society organizations to more effectively and purposefully pursue their missions in service of their communities. -

Aportaciones Al Desarrollo De Una Ingeniería De Contenidos Docentes

Programa de doctorado Sistemas Inteligentes y Aplicaciones Numéricas en Ingeniería Órgano responsable del programa de doctorado Instituto Universitario de Sistemas Inteligentes y Aplicaciones Numéricas en Ingeniería Aportaciones al desarrollo de una ingeniería de contenidos docentes Autora: María Dolores Afonso Suárez Director: Co-director: Cayetano Guerra Artal Francisco Mario Hernández Tejera Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, enero 2013 A mis tres amores A mi familia Agradecimientos Quiero dar las gracias a todos los que me han apoyado. A los que me han dado ánimos porque todas esas atenciones han sido para mí muy valiosas. En primer lugar a mi querido director de tesis, Cayetano Guerra Artal, por su empuje y a mi querido codirector Francisco Mario Hernández Tejera por su paciencia. A Jesús García por estar ahí. Y a José Antonio Medina y Gordon Sutcliffe por sus inestimables aportaciones de último momento. A los profesores de la Universidad de Vilnius que en todo momento me han mostrado su interés por el trabajo realizado. Finalmente y de forma muy especial, a todos los profesionales que han participado en los proyectos PROMETEO e IESCampus. A todos, gracias. Índice general Resumen ............................................................................................................................................... xix 1. Introducción ........................................................................................................................................ 1 La ingeniería ....................................................................................................................................... -

Dilemmas of Platform Startups

DILEMMAS OF PLATFORM STARTUPS Joni Salminen D.Sc. (Econ.) [email protected] Marketing department, Turku School of Economics Abstract This paper explores the strategic problems of platform startups on the Internet: their identification and discovery of linkages between them form its contribution to the platform literature. The author argues that the chicken-and-egg problem cannot be solved solely with pricing in the online context – in fact, setting the price zero will result in a monetization dilemma, whereas drawing users from dominant platforms sets the startup vulnerable to their strategic behavior, a condition termed remora’s curse. To correctly approach strategic problems in the platform business, startup entrepreneurs should consider them holistically, carefully examining the linkages between strategic dilemmas and their solutions. Keywords: platforms, two-sided markets, startups, chicken-and-egg problem 1. Introduction 1.1 Research gap Approximately a decade ago, platforms began to receive the attention of scholars. Entering the vocabulary of economics, two-sided markets (Rochet & Tirole 2003) have become the focus of increased research interest in the field of industrial economics. The recent surge of platforms has been observed across industries, and businesses have swiftly adopted the platform strategy and terminology (Hagiu 2009). Eisenmann, Parker, and Van Alstyne (2011, 1272) found that “60 of the world’s 100 largest corporations earn at least half of their revenue from platform markets.” Related terms such as app marketplaces and ecosystem have gained popularity in other fields (see Jansen & Bloemendal 2013). Overall, the implications of two- sidedness have spread from economics to other disciplines such as information systems (Casey & Töyli 2012), strategic management (Economides & Katsamakas 2006), and marketing (Sawhney, Verona, & Prandelli 2005).