The Next Segment an Explosion of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification

Science Classification Pupil Workbook Year 5 Unit 5 Name: 2 3 Existing Knowledge: Why do we put living things into different groups and what are the groups that we can separate them into? You can think about the animals in the picture and all the others that you know. 4 Session 1: How do we classify animals with a backbone? Key Knowledge Key Vocabulary Animals known as vertebrates have a spinal column. Vertebrates Some vertebrates are warm-blooded meaning that they Species maintain a consistent body temperature. Some are cold- Habitat blooded, meaning they need to move around to warm up or cool down. Spinal column Vertebrates are split into five main groups known as Warm-blooded/Cold- mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds and fish. blooded Task: Look at the picture here and think about the different groups that each animal is part of. How is each different to the others and which other animals share similar characteristics? Write your ideas here: __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ 5 How do we classify animals with a backbone? Vertebrates are the most advanced organisms on Earth. The traits that make all of the animals in this group special are -

Six3 Demarcates the Anterior-Most Developing Brain Region In

Steinmetz et al. EvoDevo 2010, 1:14 http://www.evodevojournal.com/content/1/1/14 RESEARCH Open Access Six3 demarcates the anterior-most developing brain region in bilaterian animals Patrick RH Steinmetz1,6†, Rolf Urbach2†, Nico Posnien3,7, Joakim Eriksson4,8, Roman P Kostyuchenko5, Carlo Brena4, Keren Guy1, Michael Akam4*, Gregor Bucher3*, Detlev Arendt1* Abstract Background: The heads of annelids (earthworms, polychaetes, and others) and arthropods (insects, myriapods, spiders, and others) and the arthropod-related onychophorans (velvet worms) show similar brain architecture and for this reason have long been considered homologous. However, this view is challenged by the ‘new phylogeny’ placing arthropods and annelids into distinct superphyla, Ecdysozoa and Lophotrochozoa, together with many other phyla lacking elaborate heads or brains. To compare the organisation of annelid and arthropod heads and brains at the molecular level, we investigated head regionalisation genes in various groups. Regionalisation genes subdivide developing animals into molecular regions and can be used to align head regions between remote animal phyla. Results: We find that in the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii, expression of the homeobox gene six3 defines the apical region of the larval body, peripherally overlapping the equatorial otx+ expression. The six3+ and otx+ regions thus define the developing head in anterior-to-posterior sequence. In another annelid, the earthworm Pristina, as well as in the onychophoran Euperipatoides, the centipede Strigamia and the insects Tribolium and Drosophila,asix3/optix+ region likewise demarcates the tip of the developing animal, followed by a more posterior otx/otd+ region. Identification of six3+ head neuroectoderm in Drosophila reveals that this region gives rise to median neurosecretory brain parts, as is also the case in annelids. -

Clustered Brachiopod Hox Genes Are Not Expressed Collinearly and Are

Clustered brachiopod Hox genes are not expressed PNAS PLUS collinearly and are associated with lophotrochozoan novelties Sabrina M. Schiemanna,1, José M. Martín-Durána,1, Aina Børvea, Bruno C. Vellutinia, Yale J. Passamaneckb, and Andreas Hejnol1,a,2 aSars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology, University of Bergen, Bergen 5006, Norway and bKewalo Marine Laboratory, Pacific Biosciences Research Center, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 Edited by Sean B. Carroll, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, and approved January 19, 2017 (received for review August 30, 2016) Temporal collinearity is often considered the main force preserving viding spatial information (29). They also are involved in Hox gene clusters in animal genomes. Studies that combine patterning different tissues (30), and often have been recruited genomic and gene expression data are scarce, however, particularly for the evolution and development of novel morphological traits, in invertebrates like the Lophotrochozoa. As a result, the temporal such as vertebrate limbs (31, 32), cephalopod funnels and arms collinearity hypothesis is currently built on poorly supported foun- (28), and beetle horns (33). dations. Here we characterize the complement, cluster, and expres- Thus, it is not surprising that Hox genes show diverse ar- sion of Hox genes in two brachiopod species, Terebratalia transversa rangements regarding their genomic organization and expression and Novocrania anomala. T. transversa has a split cluster with 10 profiles in the Spiralia (34), a major animal clade that includes lab pb Hox3 Dfd Scr Lox5 Antp Lox4 Post2 Post1 genes ( , , , , , , , , ,and ), highly disparate developmental strategies and body organizations N. anomala Post1 whereas has 9 genes (apparently missing ). -

Alvinella Pompejana (Annelida)

MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 34: 267-274, 1986 Published December 19 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Tubes of deep sea hydrothermal vent worms Riftia pachyptila (Vestimentif era) and Alvinella pompejana (Annelida) ' CNRS Centre de Biologie Cellulaire, 67 Rue Maurice Gunsbourg, 94200 Ivry sur Seine, France Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lancaster, Bailrigg. Lancaster LA1 4YQ. England ABSTRACT: The aim of this study was to compare the structure and chemistry of the dwelling tubes of 2 invertebrate species living close to deep sea hydrothermal vents at 12"48'N, 103'56'W and 2600 m depth and collected during April 1984. The Riftia pachyptila tube is formed of a chitin proteoglycan/ protein complex whereas the Alvinella pompejana tube is made from an unusually stable glycoprotein matrix containing a high level of elemental sulfur. The A. pompejana tube is physically and chemically more stable and encloses bacteria within the tube wall material. INTRODUCTION the submersible Cyana in April 1984 during the Biocy- arise cruise (12"48'N, 103O56'W). Tubes were pre- The Pompeii worm Alvinella pompejana, a poly- served in alcohol, or fixed in formol-saline, or simply chaetous annelid, and Riftia pachyptila, previously rinsed and air-dried. considered as pogonophoran but now placed in the Some pieces of tubes were post-fixed with osmium putative phylum Vestimentifera (Jones 1985), are tetroxide (1 O/O final concentration) and embedded in found at a depth of 2600 m around deep sea hydrother- Durcupan. Thin sections were stained with aqueous mal vents. R. pachyptila lives where the vent water uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a (anoxic, rich in hydrogen sulphide, temperatures up to Phillips EM 201 TEM at the Centre de Biologie 15°C) mixes with surrounding seawater (oxygenated, Cellulaire, CNRS, Ivry (France). -

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J

Tropical Marine Invertebrates CAS BI 569 Phylum ANNELIDA by J. R. Finnerty Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “BILATERIA” (=TRIPLOBLASTICA) Bilateral symmetry (?) Mesoderm (triploblasty) Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA “COELOMATA” True coelom Coelomata gut cavity endoderm mesoderm coelom ectoderm [note: dorso-ventral inversion] Phylum ANNELIDA Porifera Ctenophora Cnidaria Deuterostomia Ecdysozoa Lophotrochozoa Chordata Arthropoda Annelida Hemichordata Onychophora Mollusca Echinodermata Nematoda Platyhelminthes Acoelomorpha Silicispongiae Calcispongia PROTOSTOMIA PROTOSTOMIA “first mouth” blastopore contributes to mouth ventral nerve cord The Blastopore ! Forms during gastrulation ectoderm blastocoel blastocoel endoderm gut blastoderm BLASTULA blastopore The Gut “internal, epithelium-lined cavity for the digestion and absorption of food sponges lack a gut simplest gut = blind sac (Cnidaria) blastopore gives rise to dual- function mouth/anus through-guts evolve later Protostome = blastopore contributes to the mouth Deuterostome = blastopore becomes the anus; mouth is a second opening Protostomy blastopore mouth anus Deuterostomy blastopore -

Whole-Head Recording of Chemosensory Activity in the Marine Annelid Platynereis Dumerilii

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/391920; this version posted August 14, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Whole-head recording of chemosensory activity in the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii Thomas Chartier1, Joran Deschamps2, Wiebke Dürichen1, Gáspár Jékely3, Detlev Arendt1 1 Developmental Biology Unit, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Meyerhofstraße 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 2 Cell Biology & Biophysics Unit, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Meyerhofstraße 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany 3 Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, Spemannstraße 35, 72076 Tübingen, Germany Authors for correspondence : Detlev Arendt : [email protected] Thomas Chartier : [email protected] Submitted cover image: calcium response of the nuchal organs to a chemical stimulant in a 6-days-old Platynereis juvenile bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/391920; this version posted August 14, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Chemical detection is key to various behaviours in both marine and terrestrial animals. Marine species, though highly diverse, have been underrepresented so far in studies on chemosensory systems, and our knowledge mostly concerns the detection of airborne cues. A broader comparative approach is therefore desirable. Marine annelid worms with their rich behavioural repertoire represent attractive models for chemosensory studies. -

Invertebrates

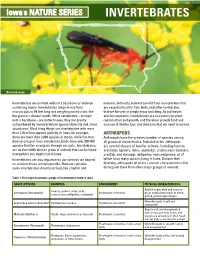

' INVERTEBRATES Braconid wasp Invertebrates are animals without a backbone or skeleton mussels. Indirectly, humans benefit from invertebrates that containing bones. Invertebrates range in size from are essential food for fish, birds, and other vertebrates microscopic to 59 feet long and weighing nearly a ton, like that we harvest or simply enjoy watching. As pollinators the giant or colossal squids. While vertebrates – animals and decomposers, invertebrates are necessary for plant with a backbone – are better known, they are greatly reproduction and growth, and therefore provide food and outnumbered by invertebrates in species diversity and sheer sources of shelter, fuel, and medicine that we need to survive. abundance. Most living things are invertebrates with more than 1.25 million species globally. In Iowa, for example, ARTHROPODS there are more than 2,000 species of moths, while the most Arthropods have the greatest number of species among diverse group of Iowa vertebrates, birds, have only 300-400 all groups of invertebrates. Included in the arthropods species that live or migrate through our state. Invertebrates are several classes of familiar animals, including insects, are an incredibly diverse group of animals that can be found arachnids (spiders, mites, and ticks), crustaceans (lobsters, everywhere you might look in Iowa. crayfish, and shrimps), millipedes, and centipedes, all of Invertebrates are also important to our survival; we depend which have many species living in Iowa. Despite their on services these animals provide. Humans consume diversity, arthropods all share common characteristics that some invertebrates directly as food, like crayfish and distinguish them from other major groups of animals. Table 1: Five major taxonomic groups of invertebrates found in Iowa. -

Evolutionary Crossroads in Developmental Biology: Annelids David E

PRIMER SERIES PRIMER 2643 Development 139, 2643-2653 (2012) doi:10.1242/dev.074724 © 2012. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: annelids David E. K. Ferrier* Summary whole to allow more robust comparisons with other phyla, as well Annelids (the segmented worms) have a long history in studies as for understanding the evolution of diversity. Much of annelid of animal developmental biology, particularly with regards to evolutionary developmental biology research, although by no their cleavage patterns during early development and their means all of it, has tended to concentrate on three particular taxa: neurobiology. With the relatively recent reorganisation of the the polychaete (see Glossary, Box 1) Platynereis dumerilii; the phylogeny of the animal kingdom, and the distinction of the polychaete Capitella teleta (previously known as Capitella sp.); super-phyla Ecdysozoa and Lophotrochozoa, an extra stimulus and the oligochaete (see Glossary, Box 1) leeches, such as for studying this phylum has arisen. As one of the major phyla Helobdella. Even within this small selection of annelids, a good within Lophotrochozoa, Annelida are playing an important role range of the diversity in annelid biology is evident. Both in deducing the developmental biology of the last common polychaetes are marine, whereas Helobdella is a freshwater ancestor of the protostomes and deuterostomes, an animal from inhabitant. The polychaetes P. dumerilii and C. teleta are indirect which >98% of all described animal species evolved. developers (see Glossary, Box 1), with a larval stage followed by metamorphosis into the adult form, whereas Helobdella is a direct Key words: Annelida, Polychaetes, Segmentation, Regeneration, developer (see Glossary, Box 1), with the embryo developing into Central nervous system the worm form without passing through a swimming larval stage. -

Discovering Our Heritage

The Alabama Outdoor Classroom Program is a partnership between: Welcome to Our School’s What is a BioBlitz? A BioBlitz is an event during which a group of volunteers, students, scientists, educators or others work in teams to find and identify as many species of plants, animals, microbes, fungi, and other organisms as possible that inhabit the selected area. Schoolyard BioBlitz by National Geographic http://www.nationalgeographic.org/media/s choolyard-bioblitz/ Let’s Talk Taxonomy! Lets Classify! First, in what Kingdom does it belong? Animilia Plantae Fungi Protists Eubacteria Archaebacteria Plantae or Plant Kingdom All flowering plants, mosses and ferns They are autotrophs (organisms that form nutritional organic substances from inorganic substances) Second largest kingdom Range from tiny green mosses to trees Life on earth would not exist without plants. Why? How to I classify plants? Types of Plants Mosses are small flowerless plants that grow in dense clumps or mats. Forbs – A herbaceous flowering plant other than a grass. It could be an annual or a perineal. Grasses, Sedges, & Rushes – A plant that has long narrow leaves, jointed stems, and spikes of small, wind-pollinated flowers. Woody Vines and Semi-woody Plants – A plant that has a woody stem but can not hold itself upright/Plants that have a woody like stem Shrubs are plants with woody stems, smaller than a tree, and have several main stems arising from near the ground Ferns are flowerless plants that have feathery or leafy fronds and reproduces by spores. Trees are woody perennial plants, typically having a single stem or trunk that is at least 13 feet tall and bearing lateral branches at some distance from the ground Fungi Kingdom includes mushrooms, rusts, smuts, puffballs, truffles, morels, molds, and yeasts. -

A Review of Australian Conescharellinidae (Bryozoa: Cheilostomata)

Memoirs of Museum Victoria 61(2): 135–182 (2004) ISSN 1447-2546 (Print) 1447-2554 (On-line) http://www.museum.vic.gov.au/memoirs/index.asp A review of Australian Conescharellinidae (Bryozoa: Cheilostomata) PHILIP E. BOCK1, 2 AND PATRICIA L. COOK2 1 School of Ecology and Environment, Deakin University, Melbourne Campus, Burwood Highway, Burwood, Vic. 3125. ([email protected]) 2 Honorary Associate, Marine Biology Section, Museum Victoria, GPO Box 666E, Melbourne, Vic. 3001, Australia Abstract Bock, P.E. and Cook, P.L. 2004. A review of Australian Conescharellinidae (Bryozoa: Cheilostomata). Memoirs of Museum Victoria 61(2): 135–182. The family Conescharellinidae Levinsen is defined and is regarded as comprising seven cheilostome genera (Conescharellina, Bipora, Trochosodon, Flabellopora, Zeuglopora, Crucescharellina and Ptoboroa). The astogeny of colonies, that consists of frontally budded zooids with “reversed” orientation, is briefly described and compared between genera. The morphology of zooids and heterozooids is defined and keys to genera and Australian species are provided. Taxa that were first described from Australia or from reliable subsequent records are redescribed and illustrated where possible. Australian specimens that have been identified as non-Australian species, have generally been found to be dis- tinct and are here redescribed as new species. Some non-Australian records of specimens previously assigned to Australian species have also been re-examined. These are described and sometimes referred to other taxa. Altogether, eight previously described species that have not been found in the present material are discussed and 27 taxa are described from collections, principally from the eastern and southern coasts of Australia and from the Tertiary of Victoria. -

The Neuroanatomy of the Siboglinid Riftia Pachyptila Highlights Sedentarian Annelid Nervous System Evolution

RESEARCH ARTICLE The neuroanatomy of the siboglinid Riftia pachyptila highlights sedentarian annelid nervous system evolution 1 2 1,3 Nadezhda N. Rimskaya-KorsakovaID *, Sergey V. Galkin , Vladimir V. Malakhov 1 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia, 2 Laboratory of Ocean Benthic Fauna, Shirshov Institute of Oceanology of the Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, Russia, 3 Far Eastern Federal University, Vladivostok, Russia a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Tracing the evolution of the siboglinid group, peculiar group of marine gutless annelids, requires the detailed study of the fragmentarily explored central nervous system of vesti- mentiferans and other siboglinids. 3D reconstructions of the neuroanatomy of Riftia OPEN ACCESS revealed that the ªbrainº of adult vestimentiferans is a fusion product of the supraesophageal Citation: Rimskaya-Korsakova NN, Galkin SV, and subesophageal ganglia. The supraesophageal ganglion-like area contains the following Malakhov VV (2018) The neuroanatomy of the siboglinid Riftia pachyptila highlights sedentarian neural structures that are homologous to the annelid elements: the peripheral perikarya of annelid nervous system evolution. PLoS ONE 13 the brain lobes, two main transverse commissures, mushroom-like structures, commissural (12): e0198271. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. cell cluster, and the circumesophageal connectives with two roots which give rise to the palp pone.0198271 neurites. Three pairs of giant perikarya are located in the supraesophageal ganglion, giving Editor: Andreas Hejnol, Universitetet i Bergen, rise to the paired giant axons. The circumesophageal connectives run to the VNC. The sub- NORWAY esophageal ganglion-like area contains a tripartite ventral aggregation of perikarya (= the Received: May 14, 2018 postoral ganglion of the VNC) interconnected by the subenteral commissure. -

Discovery of Methylfarnesoate As the Annelid Brain Hormone Reveals An

RESEARCH ARTICLE Discovery of methylfarnesoate as the annelid brain hormone reveals an ancient role of sesquiterpenoids in reproduction Sven Schenk1,2*, Christian Krauditsch1, Peter Fru¨ hauf2,3, Christopher Gerner2,3, Florian Raible1,2* 1Max F. Perutz Laboratories, University of Vienna, Vienna Biocenter (VBC), Vienna, Austria; 2Research Platform Marine Rhythms of Life, University of Vienna, Vienna Biocenter (VBC), Vienna, Austria; 3Institute for Analytical Chemistry, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Abstract Animals require molecular signals to determine when to divert resources from somatic functions to reproduction. This decision is vital in animals that reproduce in an all-or-nothing mode, such as bristle worms: females committed to reproduction spend roughly half their body mass for yolk and egg production; following mass spawning, the parents die. An enigmatic brain hormone activity suppresses reproduction. We now identify this hormone as the sesquiterpenoid methylfarnesoate. Methylfarnesoate suppresses transcript levels of the yolk precursor Vitellogenin both in cell culture and in vivo, directly inhibiting a central energy–costly step of reproductive maturation. We reveal that contrary to common assumptions, sesquiterpenoids are ancient animal hormones present in marine and terrestrial lophotrochozoans. In turn, insecticides targeting this pathway suppress vitellogenesis in cultured worm cells. These findings challenge current views of animal hormone evolution, and indicate that non-target species and marine ecosystems are susceptible to commonly used insect larvicides. DOI: 10.7554/eLife.17126.001 *For correspondence: sven. [email protected] (SS); florian. [email protected] (FR) Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no As animals rely on limited energy resources, they require regulatory mechanisms to decide how to competing interests exist.