On the Relation of the Arthropod Head to the Annelid Prostomium. by Edwin S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification

Science Classification Pupil Workbook Year 5 Unit 5 Name: 2 3 Existing Knowledge: Why do we put living things into different groups and what are the groups that we can separate them into? You can think about the animals in the picture and all the others that you know. 4 Session 1: How do we classify animals with a backbone? Key Knowledge Key Vocabulary Animals known as vertebrates have a spinal column. Vertebrates Some vertebrates are warm-blooded meaning that they Species maintain a consistent body temperature. Some are cold- Habitat blooded, meaning they need to move around to warm up or cool down. Spinal column Vertebrates are split into five main groups known as Warm-blooded/Cold- mammals, amphibians, reptiles, birds and fish. blooded Task: Look at the picture here and think about the different groups that each animal is part of. How is each different to the others and which other animals share similar characteristics? Write your ideas here: __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ __________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ 5 How do we classify animals with a backbone? Vertebrates are the most advanced organisms on Earth. The traits that make all of the animals in this group special are -

Introduction to Arthropod Groups What Is Entomology?

Entomology 340 Introduction to Arthropod Groups What is Entomology? The study of insects (and their near relatives). Species Diversity PLANTS INSECTS OTHER ANIMALS OTHER ARTHROPODS How many kinds of insects are there in the world? • 1,000,0001,000,000 speciesspecies knownknown Possibly 3,000,000 unidentified species Insects & Relatives 100,000 species in N America 1,000 in a typical backyard Mostly beneficial or harmless Pollination Food for birds and fish Produce honey, wax, shellac, silk Less than 3% are pests Destroy food crops, ornamentals Attack humans and pets Transmit disease Classification of Japanese Beetle Kingdom Animalia Phylum Arthropoda Class Insecta Order Coleoptera Family Scarabaeidae Genus Popillia Species japonica Arthropoda (jointed foot) Arachnida -Spiders, Ticks, Mites, Scorpions Xiphosura -Horseshoe crabs Crustacea -Sowbugs, Pillbugs, Crabs, Shrimp Diplopoda - Millipedes Chilopoda - Centipedes Symphyla - Symphylans Insecta - Insects Shared Characteristics of Phylum Arthropoda - Segmented bodies are arranged into regions, called tagmata (in insects = head, thorax, abdomen). - Paired appendages (e.g., legs, antennae) are jointed. - Posess chitinous exoskeletion that must be shed during growth. - Have bilateral symmetry. - Nervous system is ventral (belly) and the circulatory system is open and dorsal (back). Arthropod Groups Mouthpart characteristics are divided arthropods into two large groups •Chelicerates (Scissors-like) •Mandibulates (Pliers-like) Arthropod Groups Chelicerate Arachnida -Spiders, -

Phylum Arthropod Silvia Rondon, and Mary Corp, OSU Extension Entomologist and Agronomist, Respectively Hermiston Research and Extension Center, Hermiston, Oregon

Phylum Arthropod Silvia Rondon, and Mary Corp, OSU Extension Entomologist and Agronomist, respectively Hermiston Research and Extension Center, Hermiston, Oregon Member of the Phyllum Arthropoda can be found in the seas, in fresh water, on land, or even flying freely; a group with amazing differences of structure, and so abundant that all the other animals taken together are less than 1/6 as many as the arthropods. Well-known members of this group are the Kingdom lobsters, crayfish and crabs; scorpions, spiders, mites, ticks, Phylum Phylum Phylum Class the centipedes and millipedes; and last, but not least, the Order most abundant of all, the insects. Family Genus The Phylum Arthropods consist of the following Species classes: arachnids, chilopods, diplopods, crustaceans and hexapods (insects). All arthropods possess: • Exoskeleton. A hard protective covering around the outside of the body (divided by sutures into plates called sclerites). An insect's exoskeleton (integument) serves as a protective covering over the body, but also as a surface for muscle attachment, a water-tight barrier against desiccation, and a sensory interface with the environment. It is a multi-layered structure with four functional regions: epicuticle (top layer), procuticle, epidermis, and basement membrane. • Segmented body • Jointed limbs and jointed mouthparts that allow extensive specialization • Bilateral symmetry, whereby a central line can divide the body Insect molting or removing its into two identical halves, left and right exoesqueleton • Ventral nerve -

Comparative Neuroanatomy of Mollusks and Nemerteans in the Context of Deep Metazoan Phylogeny

Comparative Neuroanatomy of Mollusks and Nemerteans in the Context of Deep Metazoan Phylogeny Von der Fakultät für Mathematik, Informatik und Naturwissenschaften der RWTH Aachen University zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Biologin Simone Faller aus Frankfurt am Main Berichter: Privatdozent Dr. Rudolf Loesel Universitätsprofessor Dr. Peter Bräunig Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 09. März 2012 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfügbar. Contents 1 General Introduction 1 Deep Metazoan Phylogeny 1 Neurophylogeny 2 Mollusca 5 Nemertea 6 Aim of the thesis 7 2 Neuroanatomy of Minor Mollusca 9 Introduction 9 Material and Methods 10 Results 12 Caudofoveata 12 Scutopus ventrolineatus 12 Falcidens crossotus 16 Solenogastres 16 Dorymenia sarsii 16 Polyplacophora 20 Lepidochitona cinerea 20 Acanthochitona crinita 20 Scaphopoda 22 Antalis entalis 22 Entalina quinquangularis 24 Discussion 25 Structure of the brain and nerve cords 25 Caudofoveata 25 Solenogastres 26 Polyplacophora 27 Scaphopoda 27 i CONTENTS Evolutionary considerations 28 Relationship among non-conchiferan molluscan taxa 28 Position of the Scaphopoda within Conchifera 29 Position of Mollusca within Protostomia 30 3 Neuroanatomy of Nemertea 33 Introduction 33 Material and Methods 34 Results 35 Brain 35 Cerebral organ 38 Nerve cords and peripheral nervous system 38 Discussion 38 Peripheral nervous system 40 Central nervous system 40 In search for the urbilaterian brain 42 4 General Discussion 45 Evolution of higher brain centers 46 Neuroanatomical glossary and data matrix – Essential steps toward a cladistic analysis of neuroanatomical data 49 5 Summary 53 6 Zusammenfassung 57 7 References 61 Danksagung 75 Lebenslauf 79 ii iii 1 General Introduction Deep Metazoan Phylogeny The concept of phylogeny follows directly from the theory of evolution as published by Charles Darwin in The origin of species (1859). -

The Arthropod Phylum Phyla a Major Groups of Organisms

Lab 1: Arthropod Classification Name: _______________________________ Hierarchical Classification System Classification systems enable us to impart order to a complex environment. In biology, organisms may be grouped according to their overall similarity (a classification method known as phenetics) or according to their evolutionary relationships (a classification system known as cladistics). Most modern scientists tend to adopt a cladistic approach when classifying organisms. In biology, organisms are given a generic name (reflecting the genus of the organisms), and a specific name (reflecting the species of the organism). A genus is a group of closely related organisms. Genera which are closely related are grouped into a higher (less specific) category known as a family. Families are grouped into orders, and orders into classes. Classes of organisms are grouped into phyla, and phyla are grouped into kingdoms. Domains are the highest taxonomic rank of organisms. Domain Bacteria, Eubacteria, Eukarya Kingdom Plants, Animals, Fungus, Protists Phylum Cnidaria, Annelida, Arthropoda Class Insecta, Arachnida, Crustacea Order Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, Diptera Family Tipulidae, Apidae, Scarabeidae Genus Scaptia, Euglossa, Anastrangalia Species beyonceae, bazinga, laetifica Glossary of Phylogenetic Terms Phylogeny: interrelationships of organisms based on evolution Systematics: the study of the diversity of organisms, which attempts to organize or rationalize diversity in terms of phylogeny Taxonomy: the technical aspects of systematics, dealing with the formal description of species, establishing rankings of groups, and general principles of classification and naming Phylogenetic Tree (cladogram): a diagrammatic representation of the presumed line of descent of a group of organisms. Thus, a phylogenetic tree is actually a hypothesis regarding the evolutionary history of a group of organisms. -

Onychophorology, the Study of Velvet Worms

Uniciencia Vol. 35(1), pp. 210-230, January-June, 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/ru.35-1.13 www.revistas.una.ac.cr/uniciencia E-ISSN: 2215-3470 [email protected] CC: BY-NC-ND Onychophorology, the study of velvet worms, historical trends, landmarks, and researchers from 1826 to 2020 (a literature review) Onicoforología, el estudio de los gusanos de terciopelo, tendencias históricas, hitos e investigadores de 1826 a 2020 (Revisión de la Literatura) Onicoforologia, o estudo dos vermes aveludados, tendências históricas, marcos e pesquisadores de 1826 a 2020 (Revisão da Literatura) Julián Monge-Nájera1 Received: Mar/25/2020 • Accepted: May/18/2020 • Published: Jan/31/2021 Abstract Velvet worms, also known as peripatus or onychophorans, are a phylum of evolutionary importance that has survived all mass extinctions since the Cambrian period. They capture prey with an adhesive net that is formed in a fraction of a second. The first naturalist to formally describe them was Lansdown Guilding (1797-1831), a British priest from the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent. His life is as little known as the history of the field he initiated, Onychophorology. This is the first general history of Onychophorology, which has been divided into half-century periods. The beginning, 1826-1879, was characterized by studies from former students of famous naturalists like Cuvier and von Baer. This generation included Milne-Edwards and Blanchard, and studies were done mostly in France, Britain, and Germany. In the 1880-1929 period, research was concentrated on anatomy, behavior, biogeography, and ecology; and it is in this period when Bouvier published his mammoth monograph. -

Six3 Demarcates the Anterior-Most Developing Brain Region In

Steinmetz et al. EvoDevo 2010, 1:14 http://www.evodevojournal.com/content/1/1/14 RESEARCH Open Access Six3 demarcates the anterior-most developing brain region in bilaterian animals Patrick RH Steinmetz1,6†, Rolf Urbach2†, Nico Posnien3,7, Joakim Eriksson4,8, Roman P Kostyuchenko5, Carlo Brena4, Keren Guy1, Michael Akam4*, Gregor Bucher3*, Detlev Arendt1* Abstract Background: The heads of annelids (earthworms, polychaetes, and others) and arthropods (insects, myriapods, spiders, and others) and the arthropod-related onychophorans (velvet worms) show similar brain architecture and for this reason have long been considered homologous. However, this view is challenged by the ‘new phylogeny’ placing arthropods and annelids into distinct superphyla, Ecdysozoa and Lophotrochozoa, together with many other phyla lacking elaborate heads or brains. To compare the organisation of annelid and arthropod heads and brains at the molecular level, we investigated head regionalisation genes in various groups. Regionalisation genes subdivide developing animals into molecular regions and can be used to align head regions between remote animal phyla. Results: We find that in the marine annelid Platynereis dumerilii, expression of the homeobox gene six3 defines the apical region of the larval body, peripherally overlapping the equatorial otx+ expression. The six3+ and otx+ regions thus define the developing head in anterior-to-posterior sequence. In another annelid, the earthworm Pristina, as well as in the onychophoran Euperipatoides, the centipede Strigamia and the insects Tribolium and Drosophila,asix3/optix+ region likewise demarcates the tip of the developing animal, followed by a more posterior otx/otd+ region. Identification of six3+ head neuroectoderm in Drosophila reveals that this region gives rise to median neurosecretory brain parts, as is also the case in annelids. -

Coincidence of Photic Zone Euxinia and Impoverishment of Arthropods

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Coincidence of photic zone euxinia and impoverishment of arthropods in the aftermath of the Frasnian- Famennian biotic crisis Krzysztof Broda1*, Leszek Marynowski2, Michał Rakociński1 & Michał Zatoń1 The lowermost Famennian deposits of the Kowala quarry (Holy Cross Mountains, Poland) are becoming famous for their rich fossil content such as their abundant phosphatized arthropod remains (mostly thylacocephalans). Here, for the frst time, palaeontological and geochemical data were integrated to document abundance and diversity patterns in the context of palaeoenvironmental changes. During deposition, the generally oxic to suboxic conditions were interrupted at least twice by the onset of photic zone euxinia (PZE). Previously, PZE was considered as essential in preserving phosphatised fossils from, e.g., the famous Gogo Formation, Australia. Here, we show, however, that during PZE, the abundance of arthropods drastically dropped. The phosphorous content during PZE was also very low in comparison to that from oxic-suboxic intervals where arthropods are the most abundant. As phosphorous is essential for phosphatisation but also tends to fux of the sediment during bottom water anoxia, we propose that the PZE in such a case does not promote the fossilisation of the arthropods but instead leads to their impoverishment and non-preservation. Thus, the PZE conditions with anoxic bottom waters cannot be presumed as universal for exceptional fossil preservation by phosphatisation, and caution must be paid when interpreting the fossil abundance on the background of redox conditions. 1 Euxinic conditions in aquatic environments are defned as the presence of H2S and absence of oxygen . If such conditions occur at the chemocline in the water column, where light is available, they are defned as photic zone euxinia (PZE). -

Clustered Brachiopod Hox Genes Are Not Expressed Collinearly and Are

Clustered brachiopod Hox genes are not expressed PNAS PLUS collinearly and are associated with lophotrochozoan novelties Sabrina M. Schiemanna,1, José M. Martín-Durána,1, Aina Børvea, Bruno C. Vellutinia, Yale J. Passamaneckb, and Andreas Hejnol1,a,2 aSars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology, University of Bergen, Bergen 5006, Norway and bKewalo Marine Laboratory, Pacific Biosciences Research Center, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 Edited by Sean B. Carroll, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, and approved January 19, 2017 (received for review August 30, 2016) Temporal collinearity is often considered the main force preserving viding spatial information (29). They also are involved in Hox gene clusters in animal genomes. Studies that combine patterning different tissues (30), and often have been recruited genomic and gene expression data are scarce, however, particularly for the evolution and development of novel morphological traits, in invertebrates like the Lophotrochozoa. As a result, the temporal such as vertebrate limbs (31, 32), cephalopod funnels and arms collinearity hypothesis is currently built on poorly supported foun- (28), and beetle horns (33). dations. Here we characterize the complement, cluster, and expres- Thus, it is not surprising that Hox genes show diverse ar- sion of Hox genes in two brachiopod species, Terebratalia transversa rangements regarding their genomic organization and expression and Novocrania anomala. T. transversa has a split cluster with 10 profiles in the Spiralia (34), a major animal clade that includes lab pb Hox3 Dfd Scr Lox5 Antp Lox4 Post2 Post1 genes ( , , , , , , , , ,and ), highly disparate developmental strategies and body organizations N. anomala Post1 whereas has 9 genes (apparently missing ). -

(Includes Insects) Myriapods Pycnogonids Limulids Arachnids

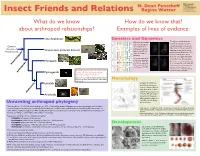

N. Dean Pentcheff Insect Friends and Relations Regina Wetzer What do we know How do we know that? about arthropod relationships? Examples of lines of evidence: Onychophorans Genetics and Genomics Genomic approaches The figures at left show the can look at patterns protein structure of opsins Common of occurrence of (visual pigments). Yellow iden- tifies areas of the protein that Ancestor of whole genes across Crustaceans (includes Insects) have important evolutionary Panarthropoda taxa to identify pat- terns of common and functional differences. This ancestry. provides information about how the opsin gene family has Cook, C. E., Smith, M. L., evolved across different taxa. Telford, M. J., Bastianello, Myriapods A., Akam, M. 2001. Hox Porter, M. L., Cronin, T. W., McClellan, Panarthropoda genes and the phylogeny D. A., Crandall, K. A. 2007. Molecular of the arthropods. Cur- characterization of crustacean visual rent Biology 11: 759-763. pigments and the evolution of pan- crustacean opsins. Molecular Biology This phylogenetic tree of the Arthropoda and Evolution 24(1): 253-268. Arthropoda Pycnogonids outlines our best current knowledge about relationships in the group. Dunn, C.W. et al. 2008. Broad phylogenetic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature Morphology 452: 745-749. Limulids Comparing similarities and differences among arthropod appendages is a fertile source of infor- Chelicerata mation about patterns of ancestry. Morphological Arachnids evidence can be espec- ially valuable because it is available for both living Unraveling arthropod phylogeny and fossil taxa. There are about 1,100,000 described arthropods – 85% of multicellular animals! Segmentation, jointed appendages, and the devel- opment of pattern-forming genes profoundly affected arthropod evolution and created the most morphologically diverse taxon on [Left:] Cotton, T. -

Study Questions 2 (Through Arthropod 1)

Study Questions 2 (through Arthropod 1) 1. Name the three embryonic germ layers found in all triploblastic animals. 2. What is a coelom? Which Phyla that we have discussed thus far have a true coelom? 3. Define cephalization. What is the name of the most primitive Phylum we have discussed that displays cephalization? 4. How is the digestive system of a Turbellarian similar to the digestive system of a Hydrozoan? Describe one way that they are different. 5. What is the function of flame cells? 6. How is the nervous system of a flatworm (Phylum Platyhelminthes) different from that of a Cnidarian? 7. Which two classes of flatworms are entirely parasitic? Describe some adaptations for parasitism that are found in these classes. 8. What are some of the major differences between Nemertine worms (Phylum Nemertea) and flatworms (Phylum Platyhelminthes)? In what major way are these two phyla similar? 9. What is a pseudocoelom? What are some of the functions of the pseudocoelom in Phylum Nematoda? 10. Nematodes have move in a characteristic whip like fashion. What aspect of their anatomy is responsible for this type of movement? 11. Describe the general structure of the Nematode nervous system. How is it different from the nervous system of Platyhelminthes? 12. What is unique about Nematode muscle cells? 13. What is unique about the way Nematode sperm move? 14. Many Nematodes are parasitic. Describe some adaptations that Nematodes have for parasitism. 15. What characteristics of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans make such an important model organism for the study of developmental genetics? 16. List two functions of the Rotifer corona. -

Alvinella Pompejana (Annelida)

MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 34: 267-274, 1986 Published December 19 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Tubes of deep sea hydrothermal vent worms Riftia pachyptila (Vestimentif era) and Alvinella pompejana (Annelida) ' CNRS Centre de Biologie Cellulaire, 67 Rue Maurice Gunsbourg, 94200 Ivry sur Seine, France Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lancaster, Bailrigg. Lancaster LA1 4YQ. England ABSTRACT: The aim of this study was to compare the structure and chemistry of the dwelling tubes of 2 invertebrate species living close to deep sea hydrothermal vents at 12"48'N, 103'56'W and 2600 m depth and collected during April 1984. The Riftia pachyptila tube is formed of a chitin proteoglycan/ protein complex whereas the Alvinella pompejana tube is made from an unusually stable glycoprotein matrix containing a high level of elemental sulfur. The A. pompejana tube is physically and chemically more stable and encloses bacteria within the tube wall material. INTRODUCTION the submersible Cyana in April 1984 during the Biocy- arise cruise (12"48'N, 103O56'W). Tubes were pre- The Pompeii worm Alvinella pompejana, a poly- served in alcohol, or fixed in formol-saline, or simply chaetous annelid, and Riftia pachyptila, previously rinsed and air-dried. considered as pogonophoran but now placed in the Some pieces of tubes were post-fixed with osmium putative phylum Vestimentifera (Jones 1985), are tetroxide (1 O/O final concentration) and embedded in found at a depth of 2600 m around deep sea hydrother- Durcupan. Thin sections were stained with aqueous mal vents. R. pachyptila lives where the vent water uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a (anoxic, rich in hydrogen sulphide, temperatures up to Phillips EM 201 TEM at the Centre de Biologie 15°C) mixes with surrounding seawater (oxygenated, Cellulaire, CNRS, Ivry (France).