World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Tanger Med Container Port, Morocco

E3S Web of Conferences 234, 00025 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202123400025 ICIES 2020 The impact of Covid-19 on the port environment: The case of Tanger Med container port, Morocco Hajar Abous 1, *, Mhamed Hamiche 2, and Mohamed El Merouani 3 1 Faculty of sciences, Abdelmalek Essaâdi University-Morocco 2 Faculty of economic sciences FSJES ,Abdelmalek Essaâdi University -Morocco 3 Faculty of sciences, Abdelmalek Essaâdi University-Morocco Abstract. The appearance of the COVID-19 virus has a huge impact on the economy, where many factories and logistics flows are affected. With global supply chains severely disrupted, production and consumption centers around the world are beginning to be affected by the situation. our study tried to measure the impact of this pandemic on the containers transport in Morocco, our work targeted the Tanger Med port due to its geographic position as the most important link between Africa and Europe, Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique was applied, this model integrates the term of lag and difference in the modeling of linear series. To verify the existence of long-term relationships, F-bond test was applied. The model was estimated on short and long term. the results were significant and has shown that the activity within Tanger Med port, experienced a shock during the pandemic period. 1 Introduction The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) also called for the maintenance Indispensable vector of globalization through which more and protection of maritime traffic and logistics chains, than 80% of the flows of raw materials and goods pass, including traffic to the hinterland, "whose role is vital for maritime transport is suffering from the pandemic due to people in these times of global crisis”. -

Trade-Watch Africa Issue 63 | August 2016

TRADE-WATCH AFRICA ISSUE 63 | AUGUST 2016 CMA CGM STRENGTHENS MOROCCAN COVERAGE DAKHLA PORT CALL ADDED TO MOROCCO SHUTTLE SERVICE Full Story On Page 3 AFRICATRADE-WATCH ISSUE 63 | AUGUST 2016 Contents 03 | African Group News CMA CGM Strengthens Moroccan Coverage, Dakhla Port Call Added To Morocco Shuttle Service / CMA CGM Leading Refrigerated Transport In Morocco / CMA CGM Offers ‘AQUAVIVA’ Container For Perishables Sector 05 | Pan Africa Regional: China-Africa Economic Forum Inks US$17 Billion In Trade Pacts / Africa50 To Mobilise US$1 Billion For Infrastructure Projects In Africa / Tokyo International Conference on African Development [TICAD-VI] / Obama Creates Advisory Council to Promote US Business Ties With Africa / Leaders Conclude 27th AU Summit With Set Of Border-Less Decisions / 14th United Nations Conference On Trade & Development [UNCTAD 14] / 2016 African Economic Outlook [AEO] Launched / African Union’s African Day of Seas and Oceans 11 | Western Africa Angola: Angola To Build Ports In Cabinda & Zaire Provinces Benin: New Mobile Cranes For Cotonou Port Cameroon: Chinese CHEC Wins Douala Port Dredging Contract / Dutch Smit Lamnalco Creates SLK Kribi Towage To Operate At Kribi Gambia: Banjul Terminal J-22 Launched Ghana: Ghana-China Trade Hits US$6.6 Billion In 2015 / GCNet Laments Unnecessary Delays In Port Clearance / President Launches Six Projects At Tema Port Nigeria: FG To Partner NPA On Maritime Security / Hadiza Bala Usman Heads NPA / Government Orders Fresh Probe On Nimasa, NPA, Others / FEC Approves Badagry Port Facilities -

Sustainable Transport in Morocco

European Scientific Journal October 2015 edition vol.11, No.29 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORT IN MOROCCO: WHAT CONTINGENCY FACTORS FOR WHICH MATURITY LEVEL? CASE OF ROAD HAULAGE “RH” SERVICE PROVIDERS IN THE REGION OF CASABLANCA METROPOLIS Abbes Elhasbi PhD Student at the University of Hassan II. National High School of Electricity and Mechanics in Casablanca- Morocco Jihad Jami Teacher-researcher at the University of Abdelmalek Essaâdi. Faculty of Legal, Economic and Social Sciences (FLESS) of Tangier- Morocco PhD in Economical Sciences, Department of Economics and Management Member of the Study Group in Economics and Territory (SGET) in FLESST Said Kammas Teacher-researcher at High School of Technical Sciences and Management, Tangier - Morocco PhD in Sciences of Management from the University of Paul Valéry Montpellier III. UFR “Economic, Mathematical and social Sciences,” - France All Founding members of SRECELD126 Abstract Dealing with sustainable transport has allowed researchers and practitioners to suggest several solutions (decoupling, inter-modality…) capable of providing, at least, part of the answers to the negative externalities caused by road haulage. Traffic congestion, sound nuisance, pollution, insecurity… are so many effects produced by the overuse of heavy goods vehicles. As regards sustainable development, Morocco has demonstrated its firm commitment to include this variable, in order to ensure an economic growth less subject to climatic vagaries, cope with energy crises and reduce the social costs. 126 Studies and Research Centre in Logistics and Development (SRECELD) 380 European Scientific Journal October 2015 edition vol.11, No.29 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 Thus, it was not until through the logistical competitiveness strategy in Morocco (program contract 2010-2015) that clear objectives and action plan related to investing and trading, as part of sustainable transport, have been set. -

Issn: 2278-6236 a Study on Improving of Port

International Journal of Advanced Research in ISSN: 2278-6236 Management and Social Sciences Impact Factor: 6.943 A STUDY ON IMPROVING OF PORT PERFORMANCE TO MINIMIZE LOGISTICS COSTS OF THE GRAIN TRANSITING BY THE TANGIER MED PORT Aziz Babounia, Research Professor, Polydisciplinary Faculty of Tetouan- Morocco, University Abdelmalek Essaâdi Ouail El Imrani, Pursuing Ph.D. at the University Abdelmalek Essaadi of Tetouan - Morocco, Research Laboratory: Management, Logistics, Governance and Applied Economics Khalid Azougagh, Pursuing Ph.D. at the University Abdelmalek Essaadi of Tetouan - Morocco, Research Laboratory: Management, Logistics, Governance and Applied Economics Abstract: The transport of goods is based on a supply chain. The total cost may include, for example, benefits of pre- and post-routing such as land transport (road and / or rail), the remuneration of armaments, insurance, freight forwarders, brokers and the cost ... port transit. The cost of the port means, all costs resulting from the provision of ships and goods through the port authority (fixed costs), tools (-variables rent) and services (variables - wages and fees) port; they are supported directly by the port, and then passed on to users through tariffs. The article proposes a literature review on the different types of logistics costs in a port, a comparative analysis of the traffic volume during a period in the old port city of Tangier and the new Tanger Med Port and finally an analysis of the existing situation, following which delays the grain have been identified at the General Cargo Terminal with a proposal as an investment project infrastructure to maximize storage spaces dedicated to grain. Keywords: Performance, Logistics, Minimizing of logistics costs, Tangier Med Port. -

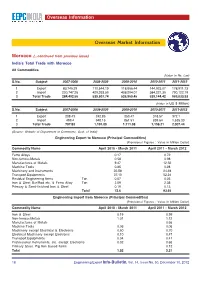

10Th December, 2012.Pmd

Overseas Information Overseas Market Information Morocco (...continued from previous issue) India’s Total Trade with Morocco All Commodities (Value in Rs. Lac) S.No. Subject 2007-2008 2008-2009 2009-2010 2010-2011 2011-2012 1 Export 83,745.29 110,544.19 118,656.44 144,923.07 178,911.73 2 Import 200,747.26 429,263.55 408,294.01 384,221.35 790,122.19 3 Total Trade 284,492.55 539,807.74 526,950.45 529,144.42 969,033.93 (Value in US $ Million) S.No. Subject 2007-2008 2008-2009 2009-2010 2010-2011 2011-2012 1 Export 208.43 242.85 250.47 318.57 372.1 2 Import 499.4 948.15 861.51 839.64 1,635.33 3 Total Trade 707.83 1,191.00 1,111.98 1,158.21 2,007.44 (Source: Website of Department of Commerce, Govt. of India) Engineering Export to Morocco (Principal Commodities) (Provisional Figures : Value in Million Dollar) Commodity Name April 2010 - March 2011 April 2011 - March 2012 Ferro Alloys 0.17 0.72 Non-ferrous Metals 0.58 0.98 Manufactures of Metals 9.47 12.32 Machine Tools 0.35 0.28 Machinery and Instruments 22.58 24.48 Transport Equipments 37.10 52.31 Residual Engineering Items Ton 0.07 0.05 Iron & Steel Bar/Rod etc. & Ferro Alloy Ton 2.09 2.38 Primary & Semi-finished Iron & Steel 0.19 0.13 Total 72.6 93.65 Engineering Import from Morocco (Principal Commodities) (Provisional Figures : Value in Million Dollar) Commodity Name April 2010 - March 2011 April 2011 - March 2012 Iron & Steel 0.19 0.99 Non-ferrous Metals 1.01 1.12 Manufactures of Metals 0.66 Machine Tools 0.06 0.06 Machinery except Electrical & Electronic 0.50 0.70 Electrical Machinery except Electronic 0.10 0.47 Transport Equipments 0.04 0.41 Professional Instruments, etc. -

United States Department of Agriculture LIST of INTERCEPTED

Bur.Ent. & P. Q. Issued May 1939 United States Department of Agriculture BUREAU OF ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT QUARANTINE SERVICE AND REGULATORY ANNOUNCEMENTS LIST OF INTERCEPTED PLANT PESTS, 1937 (List of Pests Recorded During the Period July 1, 1936, to June 30, 1937, In- clusive, as Intercepted in, on, or with Plants and Plant Products Entering United States Territory.) INTRODUCTION The period covered by this report represents the twenty-fourth year for which lists of intercepted plant pests have been issued. While the earlier reports gave the details regarding practically all organisms found on the plant material in- spected, the present paper omits many organisms entirely and summarizes the interceptions of many common or incompletely determined pests in short para- graphs, hence the detailed table contains only a fraction of the total findings. This report is based on interceptions for which determinations were received and indexed during the fiscal year. Determinations for collections made late in the year are often received after the close of the year and are included with those of the following year. The summarized records cover pests intercepted in, on, or with plants and plant products (1) imported, (2) offered for but refused entry, (3) held as ships' stores, etc., and hence not imported through customs, (4) offered for entry for immediate export or for immediate transportation and exportation in bond, and (5) in domestic shipments reaching the mainland from Hawaii and Puerto Rico. A cross-indexed file covering the more important and interesting interceptions is maintained in Washington and serves as the basis for this list. -

Trends and Developments Transport & Logistics Sector Morocco

Trends and Developments Transport & Logistics sector Morocco Presentation by MEYS Emerging Markets Research Country overview ❖ On average strong macro economic growth rates during the last ten years ❖ Performance of the agricultural sector huge impact on overall economic performance Economic growth rate Morocco (%) 800 14 700 12 600 5,9 10 500 5,2 8 400 4,7 6 4,2 4,3 300 3,8 4,0 200 4 2 3 2,8 100 2,4 0 0 1,2 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017e 2018p Cereal production (million tons) Rainfall (mm) L-axis Note: (e) estimate; (p) prognosis Note: The agricultural season begins in September and ends in May of the following year Source: HCP Maroc, Source: Ministry of Agriculture, HCP Maroc ❖ Large regional differences in income (GDP per capita) ❖ > 50% of public investments in 2 city regions: Casablanca – Settat and Rabat-Salé Investments public enterprises, state budget 2018 GDP per capita by region, 2015 (dirham) (million dirhams) Region Investment volume % Dakhla-Oued ed Dahab 74.254 Casablanca - Settat 29,910 28 Casablanca-Settat 45.847 Rabat - Salé 24, 346 23 Laâyoune-Saguia al Hamra 40.154 Marrakech - Safi 10,995 10 Rabat-Salé-Kénitra 34.271 Tanger – Tetouan – Al Hoceima 10,081 9 Guelmim-Oued Noun 30.102 Oriental 8,495 8 National 28.953 Fes - Meknes 5,695 5 Tanger-Tétouan-Al Hoceima 27.669 Benni Mellal - Knenifra 5,126 5 Souss-Massa 23.901 Souss - Massa 4,935 5 Laayoune – Sakia El Hamra 3,232 3 Béni Mellal-Khénifra 22.742 Daraa - Tafilalet 2,758 3 Fès-Meknès 20.944 Guelmin – Oued Noun 1,281 1 Oriental 20.248 Dakhla – Oued -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No. 58010-MA INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAM DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT POLICY LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF EURO 100 MILLION (US$136.7 million equivalent) TO THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO IN SUPPORT OF Public Disclosure Authorized THE URBAN TRANSPORT SECTOR February 14, 2011 Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized MOROCCO GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective as of January 31, 2010) Currency Unit Moroccan Dirham US$1.00 = MAD 8.2 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System ABBREVIATION AND ACRONYMS AFD Agence Française de Développement ANAPEC Agence Nationale de Promotion de l’Emploi et des Compétences EIB European Investment Bank CDG Caisse de Dépôts et Gestion CNDU Commission Nationale des Déplacements Urbains CPS Country Partnership Strategy CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment DGCL Direction Générale des Collectivités Locales DPL Development Policy Loan FEC Fonds d’Equipement Communal GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green House Gas IBRD International Bank for Reconstruction and Development ICR Implementation Completion Report IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary -

Policies for Sustainable Accessibility and Mobility in the Cities of Benin

Page 1 SSATP – Benin – Policies for sustainable accessibility and mobility in cities – March 2020 Policies for Sustainable Accessibility and Mobility in the Cities of Benin Page 2 SSATP – Benin – Policies for sustainable accessibility and mobility in cities – March 2020 Page 3 SSATP – Benin – Policies for sustainable accessibility and mobility in cities – March 2020 Policies for Sustainable Accessibility and Mobility in the Cities of Benin An international partnership supported by: Page 4 SSATP – Benin – Policies for sustainable accessibility and mobility in cities – March 2020 The SSATP is an international partnership to facilitate policy development and related capacity building in the transport sector in Africa. Sound policies lead to safe, reliable, and cost-effective transport, freeing people to lift themselves out of poverty and helping countries to compete internationally. * * * * * * * The SSATP is a partnership of 42 African countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe; 8 Regional Economic Communities (RECs); 2 African institutions: African Union Commission (AUC) and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA); Financing partners for the Third Development Plan: European Commission (main donor), Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), Agence Française de Développement (AFD), African Development Bank (AfDB), and World Bank (host); Many public and private national and regional organizations. * * * * * * * The SSATP gratefully acknowledges the contributions and support of member countries and its partners. -

Transport & Logistics Sector Morocco

Transport & Logistics sector Morocco Commissioned by the ministry of Foreign Afairs Business opportunities Dutch companies in Transport & Logistics sector Morocco Authors: Commissioned by : Mr. Marco Rensma Mr. Saad Hamoumi Dutch business opportunities Transport & Logistics sector Morocco About the authors Mr. Marco Rensma studied Development Economics (MSc) at the Erasmus University Rotterdam (the Netherlands) and International Relations (MSc) at the University of Amsterdam (the Netherlands). Before starting his own company MEYS Emerging Markets Research in 2010, Mr. Rensma worked for more than fifteen years in the public and private sector in the Netherlands, promoting (regional) economic growth and improving the business environment in the Netherlands. He was – among others – for six years manager and deputy director at the Chamber of Commerce in Rotterdam during which time he and his team of highly skilled professionals supported over one hundred business associations and many individual companies on how to expand their business activities. Besides being owner-director of MEYS, Mr. Rensma is a lecturer at The Hague University of Applied Sciences (the Netherlands), and coordinator of The Hague University Africa Business Program. He teaches English BA-courses in international marketing, business-to-business marketing and qualitative market research. Mr. Saad Hamoumi has a PhD in Economics specialized in Transport and International Relations. Following a research experience in the USA at UC Berkeley, he joined the private sector in Morocco. Now he brings over 29 years’ exper ience, a good deal of which is devoted to business development of national and international projects. Mr. Hamoumi launched and developed two major projects in Morocco; one is the project of International Duty Free shops; 50 shops in 8 international Moroccan Airports, and the other major project is Oriflamme Cosmetics branch of a multinational company. -

Morocco's Growth Diagnostic

The original version of the report is in French Morocco’s Growth Diagnostic Identifying Morocco’s Binding Constraints to Broad-Based Growth 4 MOROCCO’S GROWTH DIAGNOSTIC Contributors African Development Government of the MCC Bank Kingdom of Morocco Members of the analytical and Coordination: Members of the analysis team editorial team: economic: Presidency of the Government Vincent Castel John Underwood Samia Mansour Team members: Chief Economist Kaouther Abderrahim Head of the Government Stefan Osborne Gilles Nancy (SCG) Economist Marion Dovis Abdelghni Lakhdar, Guyslain Ngeleza Ishac Diwan Team Leader, Economic Economist Advisor For their special contributions, Brad Cunningham we thank: Abdelkader El Ghrib, Economist Patricia Augier Economist Emmanuel Diarra With contributions from: Mohamed Mahroug, Ashraf Tarsim Economist Management – Regional Department Ariane Gauchat Country Team Lead (North Africa) & Representation in Abdelatif Naanaa, Statistician-Economist Morocco: Dana Binnendijk Program Officer Jacob Kolster High Commission for Yacine Fal Planning Melissa Adams Social and Gender Assessment Management – Economic Complex, Ayache Khellaf, Jason Bauer Research Department: Director Finance, Investment and Trade Steve Kayizzi-Mugerwa Abdelaziz Nihou, Shimeles Abebe Director With the contribution of: Driss Charrier Other contributors (SCG): Amine Mouaffak Olivier Breteche Essaid Azzouzi Adama Moussa Thami Elmaaroufi Driss Khiati Leila Jaafor-Kilani Mohamed Hammoumi Laurence Lannes Salah Eddine Laissaoui Mohamed El Arkoubi Mohamed El -

Morocco's Request for Country of Operations Status

Morocco’s Request for Country of Operations Status Technical Assessment* 10 November 2011 * This document is provided as background reference material exclusively for participants to the EBRD SEMED Partnership Assembly on 28 November 2011. It was produced by EBRD Management for discussion with the Bank's Board of Directors at an earlier date, and may contain information that is out of date. Index 1. Introduction and Overview ................................................................................ 4 2. Political Assessment............................................................................................. 6 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 6 2.2 History ................................................................................................................... 6 2.3 Recent political reforms ........................................................................................ 6 2.4 Status of political transition................................................................................... 8 2.5 Assessment .......................................................................................................... 10 3. Transition Assessment ...................................................................................... 12 3.1 From state-led development to gradual reforms, 1956-2010 .............................. 12 3.2 Impact of the global financial crisis and the Arab Spring..................................