Thompson Island Nature Preserve Sussex County, Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 Lrrs N and S

East and Central Farming and Forest Region and Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region: 12 LRRs N and S Brad D. Lee and John M. Kabrick 12.1 Introduction snowfall occurs annually in the Ozark Highlands, the Springfield Plateau, and the St. Francois Knobs and Basins The central, unglaciated US east of the Great Plains to the MLRAs. In the southern half of the region, snowfall is Atlantic coast corresponds to the area covered by LRR N uncommon. (East and Central Farming and Forest Region) and S (Atlantic Basin Diversified Farming Region). These regions roughly correspond to the Interior Highlands, Interior Plains, 12.2.2 Physiography Appalachian Highlands, and the Northern Coastal Plains. The topography of this region ranges from broad, gently rolling plains to steep mountains. In the northern portion of 12.2 The Interior Highlands this region, much of the Springfield Plateau and the Ozark Highlands is a dissected plateau that includes gently rolling The Interior Highlands occur within the western portion of plains to steeply sloping hills with narrow valleys. Karst LRR N and includes seven MLRAs including the Ozark topography is common and the region has numerous sink- Highlands (116A), the Springfield Plateau (116B), the St. holes, caves, dry stream valleys, and springs. The region also Francois Knobs and Basins (116C), the Boston Mountains includes many scenic spring-fed rivers and streams con- (117), Arkansas Valley and Ridges (118A and 118B), and taining clear, cold water (Fig. 12.2). The elevation ranges the Ouachita Mountains (119). This region comprises from 90 m in the southeastern side of the region and rises to 176,000 km2 in southern Missouri, northern and western over 520 m on the Springfield Plateau in the western portion Arkansas, and eastern Oklahoma (Fig. -

Binney Park Trees

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!! ! ! um ! re!t bo ! ! Ar ! ! ! ! ! wn !! !!! o ! h T wic ! ! ! n k SO e r ! U r! e a N ! D ! G! P ! B ! ! E y ! ! ! AC ! ! e !! ! !! H A ! ! n V ! n ! E ! i ! !! ! ! ! B ! ! ! ! l2l!1 ! l69! !l3 ! ! ! ! ! l68 ! ! VERONA DR ! ! l!4 ! l!67 ! !7 6 ! ! l l6 ! ! ! ! ! 8 ! ! l !5 ! l6 !5 ! ! l! ! 4 ! ! d l6 ! n ! 6 e l ! g es ! l9 ! L! e re l63 ! d T !2 ! ! ! e !l6!! ! E W u ! ! ! q ! ! V IN la P ! ! TH P EL A R L l ! O s PL 8 ! ! P ld l5 ! H !! DR ie 7 !l61 ! ! F 5 C ! ts PE l ! r A po LL 5!6 l60 ! ! S ! P l ! ! ! ! E ! L ! l ! ! B l5!5 59 ! ! ! ! ! D ! ! ! l5!4! N ! ! ! 10 U ! l O ! 2 5!3 ! l!5 l l12 S ! ! ! ! ! l11 l51 ! ! ! ! ! ! 5!0 l13 ! ! !8 l l4 4 ! ! ! l1 7 l4!9 5 l4 ! !! ! 1 ! ! ll16 ! !7 ! l4!6 ! l1 ! ! ! ! ! 8 ! ! 1 l!5 ! ! !l 4 !!9! ! ! l1! ! !! 0 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2! ! 23 l! ! ! l l! ! ! ! ! ! !4 ! 21 ! ! l2 E ! ! l2!2 ! V ! !! T A ! ! ! !4 ! ! ! ! !! S 4 ! l H AY ! ! ! ENOKE W ! OW ! C H! l25 ! ! C! ! A ! E R! A B ! ! ! ! ! ! ! D ! N ! U WEBB AVE ! ! ! ! O ! ! S l4!3 ! ! ! N R L D ! TER T E l4!2 PO ! S ! E ! 1 R 4l V ! ! A ! O ! ! ! H H ! ! ! C N A O ! ! ! ! E ! R ! B I ! ! l40 D ! ! ! N ! U ! 3!9 l26 ! l O ! ! 400 ° ! t S ! ! ! Fee ! ! ! 38 l27 200 ! l 0 ! ! 10 ! ! 0 ! ! !7 ! ! l3! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! 6 ! ! ! !! !l3 ! ! !9 ! ! 35 ! 2!! ! ! !! ! 1 l! ! l 3 l! 8! ! ! 4 !3 l 2 ! ! 3ll3l2 ! ! ! 3 l!30 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Pin Oak Quercus palustris 36 White Pine Pinus strobus 2 Japanese Pagoda Styphnolobium japonicum 37 Royalty Crab Malus Royalty 3 Katsura Cercidiphyllum -

Conservation Actions

CHAPTER 4 Conservation Actions Table of Contents Take Action! Get Involved! ................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Background and Rationale ................................................................................................................. 9 Conservation Action Classification System .................................................................................... 11 Conservation Action Description ........................................................................................................ 12 Best Practices for Conservation Actions ............................................................................................. 15 International Conservation Actions ................................................................................................ 15 Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 15 Regional Conservation Actions ........................................................................................................ 19 Regional Conservation Needs Program .............................................................................................. 19 Regional Action ............................................................................................................................. -

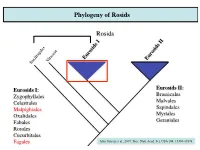

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

DE Wildlife Action Plan

DelawareDelaware WildlifeWildlife ActionAction PlanPlan Keeping Today’s Wildlife from Becoming Tomorrow’s Memory Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control Division of Fish and Wildlife 89 King Highway Dover, Delaware 19901 [email protected] Delaware Wildlife Action Plan 2007 - 2017 Submitted to: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 300 Westgate Center Drive Hadley, MA 01035-9589 September, 2006 Submitted by: Olin Allen, Biologist Brianna Barkus, Outreach Coordinator Karen Bennett, Program Manager Cover Photos by: Chris Bennett, Chuck Fullmer, Mike Trumabauer, DE Div. of Fish & Wildlife Delaware Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control 89 Kings Highway Dover DE 19901 Delaware Wildlife Action Plan Acknowledgements This project was funded, in part, through grants from the Delaware Division of Fish & Wildlife with funding from the Division of Federal Assistance, United States Fish & Wildlife Service under the State Wildlife Grants Program; and the Delaware Coastal Programs with funding from the Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under award number NA17OZ2329. We gratefully acknowledge the participation of the following individuals: Jen Adkins Sally Kepfer NV Raman Chris Bennett Gary Kreamer Ken Reynolds Melinda Carl Annie Larson Ellen Roca John Clark Wayne Lehman Bob Rufe Rick Cole Jeff Lerner Tom Saladyga Robert Coxe Rob Line Craig Shirey Janet -

Delaware's Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need

CHAPTER 1 DELAWARE’S WILDLIFE SPECIES OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED CHAPTER 1: Delaware’s Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Regional Context ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Delaware’s Animal Biodiversity .................................................................................................................... 10 State of Knowledge of Delaware’s Species ................................................................................................... 10 Delaware’s Wildlife and SGCN - presented by Taxonomic Group .................................................................. 11 Delaware’s 2015 SGCN Status Rank Tier Definitions................................................................................. 12 TIER 1 .................................................................................................................................................... 13 TIER 2 .................................................................................................................................................... 13 TIER 3 .................................................................................................................................................... 13 Mammals .................................................................................................................................................... -

Northern Pin Oak Quercus Ellipsoidalis

Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Northern Pin Oak Quercus ellipsoidalis Height: 50’ - 70’ Spread: 40’ - 60’ Site characteristics: Full sun, dry to medium moisture, well-drained soils Zone: 4 - 7 Wet/dry: Tolerates dry soils Native range: North Central United States pH: ≤ 7.5 Shape: Cylindrical shape and rounded crown; upper branches are ascending while lower branches are descending Foliage: Dark green leaves in summer, russet-red in fall Other: Elliptic acorns mature after two seasons Additional: Tolerates neutral pH better than pin oak (Quercus palustris) Pests: Oak wilt, chestnut blight, shoestring root rot, anthracnose, oak leaf blister, cankers, leaf spots and powdery mildew. Potential insect pests include scales, oak skeletonizers, leafminers, galls, oak lace bugs, borers, caterpillars and nut weevils. Jesse Saylor, MSU Jesse Saylor, Joseph O’Brien, Bugwood.org Joseph O’Brien, MSU Bert Cregg, Map indicates species’ native range. U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Content development: Dana Ellison, Tree form illustrations: Marlene Cameron. Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Bert Cregg and Robert Schutzki, Michigan State University, Departments of Horticulture and Forestry A smart urban or community landscape has a diverse combination of trees. The devastation caused by exotic pests such as Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight and emerald ash borer has taught us the importance of species diversity in our landscapes. Exotic invasive pests can devastate existing trees because many of these species may not have evolved resistance mechanisms in their native environments. In the recent case of emerald ash borer, white ash and green ash were not resistant to the pest and some communities in Michigan lost up to 20 percent of their tree cover. -

Quercus Palustris (Pin Oak Or Swamp Oak)

Quercus palustris (Pin Oak or Swamp Oak) Quercus palustris is a medium sized, deciduous tree, ideal for parklands, large gardens or avenues. Native to North America, it was introduced to Great Britain in October 2011 the early 1800s. With a broadly pyramidal crown, this tree grows to around 20m in height - one tree in Hyde Park was recorded as reaching 28m. As it matures, the lower branches begin to droop. Its most notable features is the unusual foliage which is deeply cut with pointed lobes. In the autumn it turns to fiery russets, reds and oranges. Quercus palustris adapts to a wide range of soil condi- tions though will struggle on soils with a high pH. It can cope with moderate drought, urban pollution and has a good tolerance for exposed sites. Plant Profile Name: Quercus palustris Common Name: Pin Oak or Swamp Oak Family: Fagaceae Height: approx. 20m Demands: Best on a moist, well drained, acidic soil in full sun Foliage: Deeply lobed. Bright green in spring and brilliant red and orange in autumn. Bark: Grey-brown. Smooth in younger trees developing shallows furrows with maturity Flowers: Male catkins and insignificant female flowers in spring Fruit: Almost round acorns though not prolific Quercus palustris 50-60cm girth in spring Deepdale Trees Ltd., Tithe Farm, Hatley Road, Potton, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DX. Tel: 01767 26 26 36 www.deepdale-trees.co.uk Quercus palustris (Pin Oak or Swamp Oak) ‘Pin Oak Flats’ - large areas of The name ‘pin oak’ may be almost solely Quercus palustris grow from the historical use of on the glacial plains in some areas this hardwood to make pins of North America. -

Quercus Palustris Pin Oak1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-555 October 1994 Quercus palustris Pin Oak1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Pin Oak is one of the most utilized (perhaps overused) Oaks in the midwest and eastern United States (Fig. 1). Popular due to the attractive pyramidal shape and straight, dominant trunk, even on older specimens, it exhibits chlorosis on high pH and limestone soils because of iron-deficiency and so is not highly recommended for these sites. Green, glossy leaves borne on relatively small-diameter branches give way to brilliant red to bronze fall color attracting attention in the landscape. Some brown leaves persist on the tree into the winter providing interest to some people. Others do not care to use Pin Oak because of the leaf persistence characteristic. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Quercus palustris Pronunciation: KWERK-us pal-US-triss Common name(s): Pin Oak Figure 1. Young Pin Oak. Family: Fagaceae USDA hardiness zones: 4 through 8A (Fig. 2) Availability: generally available in many areas within Origin: native to North America its hardiness range Uses: large parking lot islands (> 200 square feet in size); wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); medium-sized DESCRIPTION parking lot islands (100-200 square feet in size); medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); Height: 50 to 75 feet recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or Spread: 35 to 40 feet for median strip plantings in the highway; reclamation Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a plant; screen; shade tree; specimen; sidewalk cutout regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more (tree pit); residential street tree; tree has been or less identical crown forms successfully grown in urban areas where air pollution, Crown shape: pyramidal poor drainage, compacted soil, and/or drought are Crown density: moderate common 1. -

Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Wildlife Habitat and Conservation Landscaping Chesapeake Bay Watershed Acknowledgments Contributors: Printing was made possible through the generous funding from Adkins Arboretum; Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection and Resource Management; Chesapeake Bay Trust; Irvine Natural Science Center; Maryland Native Plant Society; National Fish and Wildlife Foundation; The Nature Conservancy, Maryland-DC Chapter; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center; and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Reviewers: species included in this guide were reviewed by the following authorities regarding native range, appropriateness for use in individual states, and availability in the nursery trade: Rodney Bartgis, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Ashton Berdine, The Nature Conservancy, West Virginia. Chris Firestone, Bureau of Forestry, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Chris Frye, State Botanist, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Mike Hollins, Sylva Native Nursery & Seed Co. William A. McAvoy, Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control. Mary Pat Rowan, Landscape Architect, Maryland Native Plant Society. Rod Simmons, Maryland Native Plant Society. Alison Sterling, Wildlife Resources Section, West Virginia Department of Natural Resources. Troy Weldy, Associate Botanist, New York Natural Heritage Program, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Graphic Design and Layout: Laurie Hewitt, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Chesapeake Bay Field Office. Special thanks to: Volunteer Carole Jelich; Christopher F. Miller, Regional Plant Materials Specialist, Natural Resource Conservation Service; and R. Harrison Weigand, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland Wildlife and Heritage Division for assistance throughout this project. -

Quercus Palustris

Quercus palustris - Pin Oak (Fagaceae) ------------------------------------------------------------------ Quercus palustris is a very popular, symmetrical -fruit is a small acorn (0.25" long) with a cap cover- shade tree that can tolerate dry or wet sites, with ing only the very top of the small nut, on a short characteristic downswept lower branches and peduncle and often in clusters of 2 or 3 ascending upper branches. When placed in the Twigs correct pH soils, Pin Oak can grow very rapidly and -greenish- to reddish-brown, turning gray by the reach great heights at maturity. second year and somewhat thin -Pin Oak is perhaps the most twiggy of all the Oaks, FEATURES and retains dead limbs (due to self-shading) in its Form interior and lower canopy for many years unless they -large shade tree are thinned out -maturing at about 100' Trunk tall x 40' wide when -bark is medium gray, being lightly furrowed into healthy under urban middle age and beyond, and slowly becoming more conditions, but even deeply furrowed with a light reddish interior bark in larger than that in the old age wild -branches are characteristically descending (angled -upright pyramidal sharply downward) on the lower one-third of the growth habit in youth, trunk, horizontal in the midde one-third, and becoming upright oval ascending on the upper one-third, sometimes with age breaking into co-dominant central leaders by middle -medium to rapid age growth rate (most rapid -branches arising directly from the trunk are in acidic, permanently numerous, thick, of relatively -

Chapter 1: Ecoregional Planning in the Interior Low Plateau

1 CHAPTER 1: ECOREGIONAL PLANNING IN THE INTERIOR LOW PLATEAU 1.1. INTRODUCTION 1.2. OVERVIEW OF PLANNING 1.2.1. Developing a Plan to Plan 1.2.2. Budget and Workplan 1.3. DESCRIPTION OF THE INTERIOR LOW PLATEAU 1.3.1. Ecological Overview 1.3.2. Ecological Systems 1.3.3. Present Land Use CHAPTER 2: PLANNING TEAMS 2.1. INTRODUCTION 2.2. THE STEERING COMMITTEE 2.3. THE CORE TEAM 2.4. TECHNICAL TEAMS 2.5. DESIGN TEAM CHAPTER 3: GATHERING THE PIECES 3.1. INTRODUCTION 3.2. DATA SOURCES AND DATA MANAGEMENT 3.2.1. Conservation Target Data 3.2.2. Geographic Information Systems 3.3. IDENTIFICATION OF CONSERVATION TARGETS, SETTING CONSERVATION GOALS, AND SELECTING TARGET ELEMENT OCCURRENCES 3.3.1. General Guidelines 3.3.2. Terrestrial Natural Communities 3.3.3. Plant Species 3.3.4. Terrestrial Invertebrates 3.3.5. Terrestrial Vertebrates (other than birds) Birds 3.3.6. Aquatic Species 3.3.7. Aquatic Communities 3.3.8. The Conservation Targets CHAPTER 4: ASSEMBLING THE PORTFOLIO 4.1. INTRODUCTION 4.2. DEVELOPING A PRELIMINARY PORTFOLIO 4.3. DESIGNING AND REFINING THE PORTFOLIO 4.3.1. Assessing Preliminary Sites 4.3.2. Representing Matrix Communities CHAPTER 5: ASSESSING THE PORTFOLIO AND SETTING PRIORITES 5.1. DESCRIPTION OF THE PORTFOLIO 5.2. IDENTIFYING ACTION SITES 5.2.1. Action Sites 5.2.2. Landscape-Scale Action Sites 5.3. MEETING CONSERVATION GOALS 5.4. PATTERNS OF THREATS AND STRATEGIES IN THE PORTFOLIO 5.4.1. Stresses and Sources of Stress 5.4.2. Strategies CHAPTER 6: IMPLEMENTING THE CONSERVATION PLAN 6.1.