The Haskell Silk Company: Manufacturers of Staple Silks Recognized As a "Standard" in the Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2019

SPRING/SUMMER 2019 CLASSIC ROLL UP GOSSAMER INTRODUCING THE... B166 B176 4” UPTURN BRIM & ROUND CROWN 3 1/2” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN GOSSAMER MINI Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection B1899H 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 3 1/4” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: SPRING/SUMMER 2019 Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester Auburn Sand, Black, Confetti, Denim Multi, White: 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester OCEAN AUBURN SAND DENIM MULTI BLACK MULTI AUBURN SAND CONFETTI DENIM MULTI AUBURN SAND BLACK BLACK MULTI BLACK BLACK MULTI TROPICAL MULTI ECRU WHITE NATURAL CONFETTI ECRU NATURAL ECRU NATURAL NAVY RATTLESNAKE WHITE DENIM MULTI BLACK RATTLESNAKE RATTLESNAKE TRUE RED WHITE CLASSIC ROLL UP GOSSAMER INTRODUCING THE... B166 B176 4” UPTURN BRIM & ROUND CROWN 3 1/2” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN GOSSAMER MINI Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection B1899H 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 50% Paper, 33% Polypropylene, 17% Polyester 3 1/4” MEDIUM BRIM & ROUND CROWN Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% Polyester Auburn Sand, Black, Denim Multi, White: Adjustable Sweatband, UPF 50+ Sun Protection 45% Paper, 35% Polypropylene, 20% -

Bale to Bolt

Activity Guide Bale to Bolt University of Massachusetts Lowell Graduate School of Education Lowell National Historical Park Connections to National Bale to Bolt is an interdisciplinary program designed to help students achieve Standards state and national standards in History/Social Science and Science and Technology. The working of standards varies from state to state, but there is and State substantial agreement on the knowledge and skill students should acquire. The Curriculum standards listed below, taken from either the national standards or Frameworks Massachusetts standards, illustrate the primary curriculum links made in Bale to Bolt. History/Social Science Students understand how the industrial revolution, the rapid expansion of slavery, and the westward movement changed the lives of Americans and led to regional tensions. (National Standards) Students will understand the effects of inventions and discoveries that have altered working and safety conditions in manufacturing and transformed daily life and free time. (Massachusetts) Students willl understand how physical characteristics influenced the growth of the textile industry in Massachusetts. (Massachusetts) Science and technology Students will understand how technology influences society through its products and processes. (National Standards) Students describe situations that illustrate how scientific and technological revolutions have changed society. (Massachusetts) 2 Bale to Bolt Activity Guide Bale to Bolt Program Description The Bale to Bolt program includes a 90-minute interpretive tour and a 90-minute hands-on workshop providing students with the opportunity to learn about the process of cloth-making both by hand and in a factory. On the tour, students discover firsthand the unique resources of Lowell and the Park. -

The Developing Years 1932-1970

National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNIFORMS The Developing Years 1932-1970 Number 5 By R. Bryce Workman 1998 A Publication of the National Park Service History Collection Office of Library, Archives and Graphics Research Harpers Ferry Center Harpers Ferry, WV TABLE OF CONTENTS nps-uniforms/5/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016 http://npshistory.com/publications/nps-uniforms/5/index.htm[8/30/18, 3:05:33 PM] National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 (Introduction) National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 INTRODUCTION The first few decades after the founding of America's system of national parks were spent by the men working in those parks first in search of an identity, then after the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 in ironing out the wrinkles in their new uniform regulations, as well as those of the new bureau. The process of fine tuning the uniform regulations to accommodate the various functions of the park ranger began in the 1930s. Until then there was only one uniform and the main focus seemed to be in trying to differentiate between the officers and the lowly rangers. The former were authorized to have their uniforms made of finer material (Elastique versus heavy wool for the ranger), and extraneous decorations of all kinds were hung on the coat to distinguish one from the other. The ranger's uniform was used for all functions where recognition was desirable: dress; patrol (when the possibility of contact with the public existed), and various other duties, such as firefighting. -

Textiles and Clothing the Macmillan Company

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. LIBRARY OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE C/^ss --SOA Book M l X TEXTILES AND CLOTHING THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO TEXTILES AXD CLOTHIXG BY ELLEX BEERS >McGO WAX. B.S. IXSTEUCTOR IX HOUSEHOLD ARTS TEACHERS COLLEGE. COLUMBIA U>aVERSITY AXD CHARLOTTE A. WAITE. M.A. HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF DOMESTIC ART JULIA RICHMAX HIGH SCHOOL, KEW YORK CITY THE MACMILLAX COMPAXY 1919 All righU, reserved Copyright, 1919, By the MACMILLAN company. Set up and electrotyped. Published February, 1919. J. S. Gushing Co. — Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. ; 155688 PREFACE This book has been written primarily to meet a need arising from the introduction of the study of textiles into the curriculum of the high school. The aim has been, there- fore, to present the subject matter in a form sufficiently simple and interesting to be grasped readily by the high school student, without sacrificing essential facts. It has not seemed desirable to explain in detail the mechanism of the various machines used in modern textile industries, but rather to show the student that the fundamental principles of textile manufacture found in the simple machines of primitive times are unchanged in the highl}^ developed and complicated machinerj^ of to-day. Minor emphasis has been given to certain necessarily technical paragraphs by printing these in type of a smaller size than that used for the body of the text. -

The Relationship of Women's Dress to the Social, Economic, and Political Conditions in Knoxville, Tennessee Between the Years 1895 to 1910

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-1971 The Relationship of Women's Dress to the Social, Economic, and Political Conditions in Knoxville, Tennessee Between the Years 1895 to 1910 Carmen Maria Abbott University of Tennessee, Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Abbott, Carmen Maria, "The Relationship of Women's Dress to the Social, Economic, and Political Conditions in Knoxville, Tennessee Between the Years 1895 to 1910. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1971. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3869 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Carmen Maria Abbott entitled "The Relationship of Women's Dress to the Social, Economic, and Political Conditions in Knoxville, Tennessee Between the Years 1895 to 1910." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Retail, Hospitality, and Tourism Management. Anna Jean Treece, Major Professor -

Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750-1950 DATS in Partnership with the V&A

Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750-1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750-1950 Text copyright © DATS, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name taught by Sue Kerry and held at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery Collections Centre on 29th November 2007. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740 -1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Front Cover - English silk tissue, 1875, Spitalfields. T.147-1972 , Image © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum 2 Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Contents Page 2. List of Illustrations 1 3. Introduction and identification checklist 3 4. Identifying Textile Types - Fibres and Yarns 4 5. Weaving and Woven Cloth Historical Framework - Looms 8 6. Identifying Basic Weave Structures – Plain Cloths 12 7. Identifying Basic Weave Structures – Figured / Ornate Cloths 17 8. -

Stampin up Retiring Accessories 2014

GRAPHIC EUR GBP EUR Retail GBP Retail Discount Discount Page Item Product Description Price Price Discount price price Not Available Embellishments 156 129392 Coaster Board Vanilla 6.95 € £ 5.50 -- -- -- 162 129723 Talking Tag Message Labels 9.50 € £ 7.25 50% 4.75 € £ 3.63 166 102023 Dazzling Diamonds Stampin' Glitter* 4.95 € £ 3.75 -- -- -- 167 123223 Melon Mambo Stampin' Emboss Powder 5.50 € £ 3.95 -- -- -- 167 124114 Pewter Stampin' Emboss Powder 5.50 € £ 3.95 25% 4.13 € £ 2.96 167 123106 Tangerine Tango Stampin' Emboss Powder 5.50 € £ 3.95 -- -- -- 167 122950 Tempting Turquoise Stampin' Emboss Powder 5.50 € £ 3.95 -- -- -- 167 123224 Wild Wasabi Stampin' Emboss Powder 5.50 € £ 3.95 -- -- -- 167 120997 Champagne Glass Glitter 4.25 € £ 3.25 30% 2.98 € £ 2.28 167 120995 Silver Glass Glitter 4.25 € £ 3.25 -- -- -- 169 127556 In Color Dahlias 9.50 € £ 7.25 -- -- -- 169 127554 Natural Designer Buttons 5.95 € £ 4.50 -- -- -- 169 130938 In Color Boutique Details 10.95 € £ 8.25 30% 7.67 € £ 5.78 170 121003 Basic 3/8" Glimmer Brads 5.95 € £ 4.50 -- -- -- 170 121006 Brights 3/8" Glimmer Brads 5.95 € £ 4.50 -- -- -- 170 129389 Hung Up Cute Clips 5.95 € £ 4.50 30% 4.17 € £ 3.15 170 118764 Vintage Trinkets Accents & Elemebts 7.25 € £ 5.50 -- -- -- 171 125577 Large Pearl Basic Jewels 5.95 € £ 4.50 -- -- -- 171 129324 Large Rinestone Basic Jewels 5.95 € £ 4.50 30% 4.17 € £ 3.15 171 130966 Delicate Details Lace Tape 11.95 € £ 8.95 30% 8.37 € £ 6.27 171 129314 Gingham Garden Designer Washi Tape 5.95 € £ 4.50 30% 4.17 € £ 3.15 173 122966 Crumb Cake -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

Industry Mapping File

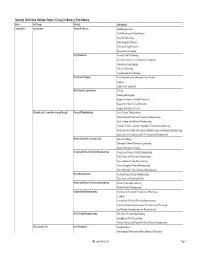

Industry Definition Outline: Sector / Group / Industry / Subindustry Sector Ind. Group Industry Subindustry Commodities Agribusiness Animal Production Animal Aquaculture Cattle Ranching and Dairy Farming Hog and Pig Farming Other Animal Production Poultry and Egg Production Sheep and Goat Farming Crop Production Fruit and Tree Nut Farming Greenhouse, Nursery, and Floriculture Production Oilseed and Grain Farming Other Crop Farming Vegetable and Melon Farming Forestry and Logging Forest Nurseries and Gathering of Forest Products Logging Timber Tract Operations Miscellaneous Agribusiness Fishing Hunting and Trapping Support Activities for Animal Production Support Activities for Crop Production Support Activities for Forestry Materials and Commodities (except Energy) Chemical Manufacturing Basic Chemical Manufacturing Other Chemical Product and Preparation Manufacturing Paint, Coating, and Adhesive Manufacturing Pesticide, Fertilizer, and Other Agricultural Chemical Manufacturing Resin, Synthetic Rubber, and Artificial Synthetic Fibers and Filaments Manufacturing Soap, Cleaning Compound, and Toilet Preparation Manufacturing Mining (except Oil, Gas, and Coal) Metal Ore Mining Nonmetallic Mineral Mining and Quarrying Support Activities for Mining Nonmetallic Mineral Product Manufacturing Cement and Concrete Product Manufacturing Clay Product and Refractory Manufacturing Glass and Glass Product Manufacturing Lime and Gypsum Product Manufacturing Other Nonmetallic Mineral Product Manufacturing Paper Manufacturing Converted Paper Product Manufacturing -

The Textile Museum Thesaurus

The Textile Museum Thesaurus Edited by Cecilia Gunzburger TM logo The Textile Museum Washington, DC This publication and the work represented herein were made possible by the Cotsen Family Foundation. Indexed by Lydia Fraser Designed by Chaves Design Printed by McArdle Printing Company, Inc. Cover image: Copyright © 2005 The Textile Museum All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means -- electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise -- without the express written permission of The Textile Museum. ISBN 0-87405-028-6 The Textile Museum 2320 S Street NW Washington DC 20008 www.textilemuseum.org Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................vii How to Use this Document.........................................................................xiii Hierarchy Overview ....................................................................................... 1 Object Hierarchy............................................................................................ 3 Material Hierarchy ....................................................................................... 47 Structure Hierarchy ..................................................................................... 55 Technique Hierarchy .................................................................................. -

Spring/Summer 2020 AMERICANA SIZES: S/M, L/XL

Spring/Summer 2020 AMERICANA SIZES: S/M, L/XL Americana 2 Braids 3 Ribbon Braids 13 Straw 15 Casual 17 Occasion 19 Pantropic 21 All hat sizes are 1SFM, unless otherwise noted. B1609H LAURA II All material contents listed exclude trim. 2 3/8” BRIM • Grosgrain ribbon trim IVORY/BLACK*, • Adjustable sweatband IVORY/NAVY, • LiteStraw® finish S/M, M/L • 100% straw • Made in the USA of globally sourced materials CUSTOMER SERVICE USA CUSTOMER SERVICE BETMAR NEW YORK SHOWROOM & DISTRIBUTION CENTER 411 Fifth Avenue, 2nd Floor 110 E. Main Street, Adamstown, PA 19501 New York, NY 10016 Tel: 800-859-4653 Fax: 888-428-7329 Tel: 212-981-9900 EUROPE CUSTOMER SERVICE Tel: +44(0) 1946 810 312 Fax: +44(0) 1946 811 087 PROUD SPONSOR OF AMERICAN MADE MATTERS® The styles, Laura II & LiteStraw® w/ Faux Leather Obi, are compliant with the standards of the Federal Trade Commission for Made in the USA of globally sourced materials. A portion of the proceeds from UPF 50+ hats will benefit the Colette Coyne Melanoma Awareness Campaign. As per the CCMAC, in order for the hats to qualify as SPF50+ the hat must have a brim minimum of 2 1/2”. Open weave styles do not qualify for SPF. _ _ Laura II Ivory/Navy Betmar® and LiteStraw® are registered trademarks of Bollman Hats. 2 BRAIDS BRAIDS B1899H GOSSAMER MINI B176 GOSSAMER 3” BRIM 3 1/2” BRIM • Medium brim & round crown • Medium brim & round crown • Charcoal adjustable sweatband • Charcoal adjustable sweatband • UPF 50+ Sun Protection • UPF 50+ Sun Protection • 50% paper, 33% polypropylene, 17% polyester • 50% paper, -

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750-1950 Identification

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A 1 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 This information pack has been produced to accompany two one-day workshops taught by Katy Wigley (Director, School of Textiles) and Mary Schoeser (Hon. V&A Senior Research Fellow), held at the V&A Clothworkers’ Centre on 19 April and 17 May 2018. The workshops are produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying woven textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the wider public and is also intended as a stand-alone guide for basic weave identification. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740–1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identifying Fibres and Fabrics Identifying Handmade Lace Front Cover: Lamy et Giraud, Brocaded silk cannetille (detail), 1878. This Lyonnais firm won a silver gilt medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle with a silk of this design, probably by Eugene Prelle, their chief designer. Its impact partly derives from the textures within the many-coloured brocaded areas and the markedly twilled cannetille ground. Courtesy Francesca Galloway. 2 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Tips for Dating 4 3.