A Comprehensive Assessment of Python and Boa Reports from the Florida Keys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rainforest Animals Question Sheet 2 the Answers to the Following Questions Can Be Found by Visiting

www.ActiveWild.com Rainforest Animals Question Sheet 2 The answers to the following questions can be found by visiting: www.activewild.com/rainforest-animals-list/ (For each question, either underline or circle the correct answer.) 1. Is the Amazonian giant centipede 6. What is the smallest species of caiman? venomous? • Black caiman • Yes • No • Spectacled caiman 2. How does the Arrau turtle withdraw its neck into its shell? • Cuvier’s dwarf caiman • With a sideways motion 7. What type of animal is a coati? • It pulls its head straight back • Mammal in the cat family • It can’t withdraw its head • Mammal in the raccoon family • Reptile in the alligator family 3. What type of animal is an aye-aye? • Monkey 8. Where is the electric eel found? • Bushbaby • South America • Lemur • Southeast Asia • Africa 4. What is the Boa Constrictor’s scientific name? 9. The goliath beetle is the world’s largest • Corallus caninus beetle. Is it able to fly? • Yes • Boa constrictor • No • Boa imperator 10. True or false: the goliath birdeater spider’s diet consists almost entirely of 5. Is the Boa constrictor venomous? birds • Yes • True • No • False Copyright © 2019. All rights reserved. 1 www.ActiveWild.com 11. True or false: the green anaconda is the 17. True or false: piranhas are apex world’s longest snake. predators, with no predators of their own? • True • True • False • False 12. Why is the hoatzin also known as the ‘stinkbird’? 18. Tarsiers are known for having large… • It is found near swamps • Eyes • It ferments leaves in its crop • Brains • It feeds on dung • Teeth 13. -

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV. Biscayne National Park By Kenneth G. Rice1, J. Hardin Waddle1, Marquette E. Crockett 2, Christopher D. Bugbee2, Brian M. Jeffery 2, and H. Franklin Percival 3 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Florida Integrated Science Center 2 University of Florida, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation 3 Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Open-File Report 2007-1057 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Rice, K.G., Waddle, J.H., Crockett, M.E., Bugbee, C.D., Jeffery, B.M., and Percival, H.F., 2007, Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV. Biscayne National Park: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2007-1057, 65 p. Online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/ofr/2007/1057/ For more information about this report, contact: Dr. Kenneth G. Rice U.S. Geological Survey Florida Integrated Science Center UF-FLREC 3205 College Ave. Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33314 USA E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 954-577-6305 Fax: 954-577-6347 Dr. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b. -

Pseudophoenix Sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park

Status update: Long-term monitoring of Sargent’s cherry palm (Pseudophoenix sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park FEBRUARY 2021 Acknowledgments Thank you to Biscayne National Park for more than three decades of support for this collaborative project on Pseudophoenix sargentii augmentation and demographic monitoring. Monitoring in 2021 was funded by the Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, under Agreement #027132. For assistance with field work and logistics we would like to thank Morgan Wagner, Michael Hoffman, Brian Lockwood, Shelby Moneysmith, Vanessa McDonough, and Astrid Santini from Biscayne National Park, Eliza Gonzalez from Montgomery Botanical Center, Dallas Hazelton from Miami-Dade County, and volunteer biologists Joseph Montes de Oca and Elizabeth Wu. Thank you to the cooperators whose excellent past work on this project has laid the foundation upon which we stand today, especially Carol Lippincott, Rob Campbell, Joyce Maschinski, Janice Duquesnel, Dena Garvue, and Sam Wright. Janice Duquesnel provided important details about the 1991-1994 outplanting efforts. Suggested citation Possley, J., J. Lange, S. Wintergerst and L. Cuni. 2021. Status update: long-term monitoring of Pseudophoenix sargentii on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park. Unpublished report from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, funded by Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services Agreement #027132. Background Pseudophoenix sargentii H.Wendl. ex Sarg., known by the common names ‘Sargent’s cherry palm’ and ‘buccaneer palm,’ is a slow-growing palm native to coastal habitats throughout the Caribbean basin, where it grows on exposed limestone or in humus or sand over limestone. Over the past century, the species has declined throughout its range, due to in part to overharvesting for use in landscaping. -

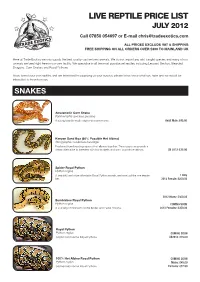

LIVE REPTILE PRICE LIST JULY 2012 Call 07850 054697 Or E-Mail [email protected]

LIVE REPTILE PRICE LIST JULY 2012 Call 07850 054697 or E-mail [email protected] ALL PRICES EXCLUDE VAT & SHIPPING FREE SHIPPING ON ALL ORDERS OVER £300 TO MAINLAND UK Here at Trade Exotics we only supply the best quality captive bred animals. We do not import any wild caught species and many of our animals are bred right here in our own facility. We specialise in all the most popular pet reptiles including Leopard Geckos, Bearded Dragons, Corn Snakes and Royal Pythons. If you breed your own reptiles and are interested in supplying us your surplus, please let us know what you have and we would be interested to hear from you. SNAKES Amelanistic Corn Snake Pantherophis guttatus guttatus A young breeder male surplus to requirements. Adult Male: £45.00 Kenyan Sand Boa (66% Possible Het Albino) Gongylophis colubrinus loveridgei Produced from breeding a pair of het albinos together. These guys can provide a cheap alternative to breeders with low budgets and want to produce albinos. CB 2012: £35.00 Spider Royal Python Python regius A beautiful and more affordable Royal Python morph, we have just the one female 1 Only left. 2012 Female: £200.00 2012 Males: £300.00 Bumblebee Royal Python Python regius COMING SOON A stunning combination of the Spider and Pastel morphs. 2012 Females: £350.00 Royal Python Python regius COMING SOON Captive bred normal Royal Pythons. CB2012: £35.00 100% Het Albino Royal Python COMING SOON Python regius Males: £45.00 Captive bred normal Royal Pythons. Females: £97.50 LEOPARD GECKOS The majority of the Leopard Geckos on our list are bred by ourselves. -

Florida Coral Reefs: Islandia

FOREWORD· In their present relatively undeveloped state, the upper Florida Keys and the adjoining waters and submerged. lands of Biscayne ~ay and the Atlantic Ocean are an enviromr~.ental element highly important to Florida ancl a valuable recreation resource for the nation. Fully aware that intensive private development would greatly alter . these values, the Secretary of the Interior directed the National Park Service and the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, assisted by the Fish and Wildlife Service, to conduct studies of the area. This interim professional report is the r~sult of these studies. It is being distributed now to solicit the comments and suggestions of interested parties. The additional information obtained in this manner will be utilized by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Outdoor Recre ation to complete the study and formulate recommendations to the Secretary· of the Interior. It is requested that comments and suggestions on this interim profes sional report be sent to the Regional Director, Southeast Region, Na tional Park Service, P. 0. Box 10008, Richmond, Virginia 23240. Material should be submitted in time to reach the Regional Director on or before August 15, 1965. ~~ Edward C. Crafts Director Director Bureau of Outdoor Recreation National Park Service Page No. FOREWORD THE STUDY 2 THE CORAL REEFS The Resource 3 The Climate 5 The Ecology 6 MAN AND THE CORAL REEFS 10 THE SITUATION Development Possibilities · 12 Significance for Preservation 12 THE OPPORTUNITIES 18 Alternative Plans 14' Plan 1 16 Plan 2 20 Plan 3 24 THE STUDY In response to interest expressed by the weekending, and vacationing are engaged Dade Co1:-1nty Board of Commissioners and in extensively. -

Biosecurity Risk Assessment

An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries by Dr Robert C Keogh February 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-007347 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-320-8 ISSN 1440-6845 An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries Publication No. 11/141 Project No. PRJ-007347 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Boa Constrictor Ssp

©ReptiFiles® — Where Better Reptile Care Begins — 2020 Boa (Boa constrictor ssp. & Boa imperator) Difficulty: Intermediate - Hard Boas (also known as boa constrictors and red-tailed boas) are a group of semi-arboreal constricting snakes native to Central and South America. They are most often found in tropical and subtropical dry to moist broadleaf forests, where they move between the trees and the leaf-covered forest floor. Boas are 5-8’ long snakes, with males tending to be significantly smaller than females, although some females grow as large as 12’. Boas typically have a relatively slender body, a rectangular head. Exact length, pattern, and coloring depends on subspecies and locality. There are 10 known subspecies of Boa, although some are more common than others in the pet trade (star indicates which are most common): Boa constrictor amarali Boa constrictor orophias Boa constrictor constrictor* Boa constrictor ortonii Boa constrictor occidentalis Boa constrictor sabogae Boa constrictor longicauda Boa imperator* Boa constrictor nebulosa Boa sigma For descriptions and photos of each subspecies, visit https://www.reptifiles.com/red-tailed-boa-care/boa-species-subspecies/. Boas are some of the most popular pet snakes in the United States. Although they can get fairly large, they tolerate humans well and make engaging pets. Boas can live upwards of 30 years with good care. Shopping List (for temporarily housing one juvenile boa) 4’ x 2’ x 2’ reptile enclosure (preferably front-opening) Dual dome heat lamp with ceramic sockets -

Wildlife Conservation Act 2010

LAWS OF MALAYSIA ONLINE VERSION OF UPDATED TEXT OF REPRINT Act 716 WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ACT 2010 As at 1 October 2014 2 WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ACT 2010 Date of Royal Assent … … 21 October 2010 Date of publication in the Gazette … … … 4 November 2010 Latest amendment made by P.U.(A)108/2014 which came into operation on ... ... ... ... … … … … 18 April 2014 3 LAWS OF MALAYSIA Act 716 WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ACT 2010 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title and commencement 2. Application 3. Interpretation PART II APPOINTMENT OF OFFICERS, ETC. 4. Appointment of officers, etc. 5. Delegation of powers 6. Power of Minister to give directions 7. Power of the Director General to issue orders 8. Carrying and use of arms PART III LICENSING PROVISIONS Chapter 1 Requirement for licence, etc. 9. Requirement for licence 4 Laws of Malaysia ACT 716 Section 10. Requirement for permit 11. Requirement for special permit Chapter 2 Application for licence, etc. 12. Application for licence, etc. 13. Additional information or document 14. Grant of licence, etc. 15. Power to impose additional conditions and to vary or revoke conditions 16. Validity of licence, etc. 17. Carrying or displaying licence, etc. 18. Change of particulars 19. Loss of licence, etc. 20. Replacement of licence, etc. 21. Assignment of licence, etc. 22. Return of licence, etc., upon expiry 23. Suspension or revocation of licence, etc. 24. Licence, etc., to be void 25. Appeals Chapter 3 Miscellaneous 26. Hunting by means of shooting 27. No licence during close season 28. Prerequisites to operate zoo, etc. 29. Prohibition of possessing, etc., snares 30. -

BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK the Florida Keys Begin with Soldier Key in the Northern Section of the Park and Continue to the South and West

CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND HISTORY GEOLOGY AND PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK The Florida Keys begin with Soldier Key in the northern section of the Park and continue to the south and west. The upper Florida Keys (from Soldier to Big Pine Key) are the remains of a shallow coral patch reef that thrived one hundred thousand or more years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch. The ocean level subsided during the following glacial period, exposing the coral to die in the air and sunlight. The coral was transformed into a stone often called coral rock, but more correctly termed Key Largo limestone. The other limestones of the Florida peninsula are related to the Key Largo; all are basically soft limestones, but with different bases. The nearby Miami oolitic limestone, for example, was formed by the precipitation of calcium carbonate from seawater into tiny oval particles (oolites),2 while farther north along the Florida east coast the coquina of the Anastasia formation was formed around the shells of Pleistocene sea creatures. When the first aboriginal peoples arrived in South Florida approximately 10,000 years ago, Biscayne Bay was a freshwater marsh or lake that extended from the rocky hills of the present- day keys to the ridge that forms the current Florida coast. The retreat of the glaciers brought about a gradual rise in global sea levels and resulted in the inundation of the basin by seawater some 4,000 years ago. Two thousand years later, the rising waters levelled off, leaving the Florida Keys, mainland, and Biscayne Bay with something similar to their current appearance.3 The keys change. -

Reptile Observation Observe Reptile Characteristics and Behaviors at the Zoo

Reptile Observation Observe reptile characteristics and behaviors at the zoo Grade 2 Objectives • Students will learn about reptiles through observation and drawing conclusions. Materials • provided zoo map Background Information • All reptiles have a backbone, breathe with lungs, and lay dry, scaly skin. • Reptiles lay eggs that have a dry leathery shell. Unlike amphibians, which have eggs with a jelly coat Key Words that must remain in water, reptiles are less dependent on water. • reptile • Basic Reptile Types • habitiat - Turtles are the only reptiles that have their “houses” on their backs. • environment - Lizards have visible, moving eyelids, limbs, and an ear opening on each side of their head. - Snakes lack limbs, eyelids, and ear openings. - Crocodilians include alligators as well as crocodiles. They are the most ancestral standards of the reptiles. • SCI.2.3.1 • SCI.2.3.2 Recommended Assessment • Have a group discussion about the observations made by students. Extensions • Assign each child or group a Reptile Treasure to discover as they move through zoo; for example, the heaviest reptile, the smallest reptile, the longest reptile, a reptile with three colors, etc. The children should report on the results of their treasure hunt when they get back to school. Reptile Observation Observe the following reptiles in Dr. Diversity’s Rain Forest Research Station while you are at the zoo. Fill in your observation on the chart. Name Timor Name of Komodo Reticulated Monitor Reptile Dragon Python Lizard Kind of snake snake snake Reptile lizard lizard lizard turtle turtle turtle crocodilian crocodilian crocodilian What it Looks Like What it Eats Interesting Facts Reptile Observation Observe the following reptiles in Dr.