Pseudophoenix Sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pseudophoenix Sargentii (Buccaneer Palm)

Pseudophoenix sargentii (Buccaneer Palm) Pseudophoenix sargentii is an attractive small palm, resembling the royal palm but can be distinquised by its trunk which is more smooth and glossy.It is a solitary, monoecious palm. It holds an open crown of pinnate leaves which can measure up to 2 m long. In habitat, it is usually found along the coast in alkaline soil. The fruit is red, hence the common name ''cherry palm<span style="line-height:20.7999992370605px">''</span><span style="line- height:1.6em">.</span> Landscape Information French Name: Palmier de guinée Pronounciation: soo-doh-FEE-niks sar-JEN- tee-eye Plant Type: Palm Origin: South Florida, the Bahamas, Belize, Cuba Heat Zones: Hardiness Zones: 10, 11, 12 Uses: Specimen, Indoor, Container Size/Shape Growth Rate: Slow Tree Shape: Upright, Palm Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Open Canopy Texture: Fine Height at Maturity: 8 to 15 m Spread at Maturity: 3 to 5 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 10 to 20 Years Plant Image Pseudophoenix sargentii (Buccaneer Palm) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Spiral Leaf Venation: Parallel Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Odd Pinnately compund Leaf Blade: 50 - 80 Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Medium Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 0 - 1.5 Flower Type: Panicle Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: Pleasant Flower Color: Green, Yellow Seasons: Year Round Trunk Trunk Has Crownshaft: True Plant Image Trunk -

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV. Biscayne National Park By Kenneth G. Rice1, J. Hardin Waddle1, Marquette E. Crockett 2, Christopher D. Bugbee2, Brian M. Jeffery 2, and H. Franklin Percival 3 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Florida Integrated Science Center 2 University of Florida, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation 3 Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Open-File Report 2007-1057 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Rice, K.G., Waddle, J.H., Crockett, M.E., Bugbee, C.D., Jeffery, B.M., and Percival, H.F., 2007, Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV. Biscayne National Park: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2007-1057, 65 p. Online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/ofr/2007/1057/ For more information about this report, contact: Dr. Kenneth G. Rice U.S. Geological Survey Florida Integrated Science Center UF-FLREC 3205 College Ave. Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33314 USA E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 954-577-6305 Fax: 954-577-6347 Dr. -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b. -

Florida Coral Reefs: Islandia

FOREWORD· In their present relatively undeveloped state, the upper Florida Keys and the adjoining waters and submerged. lands of Biscayne ~ay and the Atlantic Ocean are an enviromr~.ental element highly important to Florida ancl a valuable recreation resource for the nation. Fully aware that intensive private development would greatly alter . these values, the Secretary of the Interior directed the National Park Service and the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, assisted by the Fish and Wildlife Service, to conduct studies of the area. This interim professional report is the r~sult of these studies. It is being distributed now to solicit the comments and suggestions of interested parties. The additional information obtained in this manner will be utilized by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Outdoor Recre ation to complete the study and formulate recommendations to the Secretary· of the Interior. It is requested that comments and suggestions on this interim profes sional report be sent to the Regional Director, Southeast Region, Na tional Park Service, P. 0. Box 10008, Richmond, Virginia 23240. Material should be submitted in time to reach the Regional Director on or before August 15, 1965. ~~ Edward C. Crafts Director Director Bureau of Outdoor Recreation National Park Service Page No. FOREWORD THE STUDY 2 THE CORAL REEFS The Resource 3 The Climate 5 The Ecology 6 MAN AND THE CORAL REEFS 10 THE SITUATION Development Possibilities · 12 Significance for Preservation 12 THE OPPORTUNITIES 18 Alternative Plans 14' Plan 1 16 Plan 2 20 Plan 3 24 THE STUDY In response to interest expressed by the weekending, and vacationing are engaged Dade Co1:-1nty Board of Commissioners and in extensively. -

A Preliminary List of the Vascular Plants and Wildlife at the Village Of

A Floristic Evaluation of the Natural Plant Communities and Grounds Occurring at The Key West Botanical Garden, Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida Steven W. Woodmansee [email protected] January 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to CarolAnn Sharkey Key West Botanical Garden 5210 College Road Key West, Florida 33040 and Kate Marks Heritage Preservation 1012 14th Street, NW, Suite 1200 Washington DC 20005 Introduction The Key West Botanical Garden (KWBG) is located at 5210 College Road on Stock Island, Monroe County, Florida. It is a 7.5 acre conservation area, owned by the City of Key West. The KWBG requested that The Institute for Regional Conservation (IRC) conduct a floristic evaluation of its natural areas and grounds and to provide recommendations. Study Design On August 9-10, 2005 an inventory of all vascular plants was conducted at the KWBG. All areas of the KWBG were visited, including the newly acquired property to the south. Special attention was paid toward the remnant natural habitats. A preliminary plant list was established. Plant taxonomy generally follows Wunderlin (1998) and Bailey et al. (1976). Results Five distinct habitats were recorded for the KWBG. Two of which are human altered and are artificial being classified as developed upland and modified wetland. In addition, three natural habitats are found at the KWBG. They are coastal berm (here termed buttonwood hammock), rockland hammock, and tidal swamp habitats. Developed and Modified Habitats Garden and Developed Upland Areas The developed upland portions include the maintained garden areas as well as the cleared parking areas, building edges, and paths. -

Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae

horticulturae Review Seed Geometry in the Arecaceae Diego Gutiérrez del Pozo 1, José Javier Martín-Gómez 2 , Ángel Tocino 3 and Emilio Cervantes 2,* 1 Departamento de Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre (CYMVIS), Universidad Estatal Amazónica (UEA), Carretera Tena a Puyo Km. 44, Napo EC-150950, Ecuador; [email protected] 2 IRNASA-CSIC, Cordel de Merinas 40, E-37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Matemáticas, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Salamanca, Plaza de la Merced 1–4, 37008 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-923219606 Received: 31 August 2020; Accepted: 2 October 2020; Published: 7 October 2020 Abstract: Fruit and seed shape are important characteristics in taxonomy providing information on ecological, nutritional, and developmental aspects, but their application requires quantification. We propose a method for seed shape quantification based on the comparison of the bi-dimensional images of the seeds with geometric figures. J index is the percent of similarity of a seed image with a figure taken as a model. Models in shape quantification include geometrical figures (circle, ellipse, oval ::: ) and their derivatives, as well as other figures obtained as geometric representations of algebraic equations. The analysis is based on three sources: Published work, images available on the Internet, and seeds collected or stored in our collections. Some of the models here described are applied for the first time in seed morphology, like the superellipses, a group of bidimensional figures that represent well seed shape in species of the Calamoideae and Phoenix canariensis Hort. ex Chabaud. -

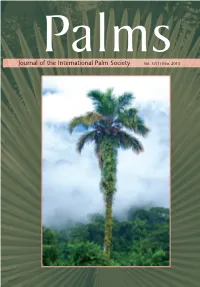

Table of Contents Than a Proper TIMOTHY K

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 57(1) Mar. 2013 PALMS Vol. 57(1) 2013 CONTENTS Island Hopping for Palms in Features 5 Micronesia D.R. H ODEL Palm News 4 Palm Literature 36 Shedding Light on the 24 Pseudophoenix Decline S. E DELMAN & J. R ICHARDS An Anatomical Character to 30 Support the Cohesive Unit of Butia Species C. M ARTEL , L. N OBLICK & F.W. S TAUFFER Phoenix dactylifera and P. sylvestris 37 in Northwestern India: A Glimpse of their Complex Relationships C. N EWTON , M. G ROS -B ALTHAZARD , S. I VORRA , L. PARADIS , J.-C. P INTAUD & J.-F. T ERRAL FRONT COVER A mighty Metroxylon amicarum , heavily laden with fruits and festooned with epiphytic ferns, mosses, algae and other plants, emerges from the low-hanging clouds near Nankurupwung in Nett, Pohnpei. See article by D.R. Hodel, p. 5. Photo by D.R. Hodel. The fruits of Pinanga insignis are arranged dichotomously BACK COVER and ripen from red to Hydriastele palauensis is a tall, slender palm with a whitish purplish black. See article by crownshaft supporting the distinctive canopy. See article by D.R. Hodel, p. 5. Photo by D.R. Hodel, p. 5. Photo by D.R. Hodel . D.R. Hodel. 3 PALMS Vol. 57(1) 2013 PALM NEWS Last year, the South American Palm Weevil ( Rhynchophorus palmarum ) was found during a survey of the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Texas . This palm-killing weevil has caused extensive damage in other parts of the world, according to Dr. Raul Villanueva, an entomologist at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Weslaco. -

A Comprehensive Assessment of Python and Boa Reports from the Florida Keys

Management of Biological Invasions (2018) Volume 9, Issue 3: 369–377 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2018.9.3.18 Open Access © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Research Article Exotic predators may threaten another island ecosystem: A comprehensive assessment of python and boa reports from the Florida Keys Emma B. Hanslowe1,4,*, James G. Duquesnel1, Ray W. Snow2, Bryan G. Falk1,2, Amy A. Yackel Adams1, Edward F. Metzger III3, Michelle A.M. Collier2 and Robert N. Reed1 1U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Avenue, Building C, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526, USA 2South Florida Natural Resources Center, Everglades National Park, 40001 State Road 9336, Homestead, Florida 33034, USA 3Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, 3205 College Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314, USA 4Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, 1417 Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, USA Author e-mails: [email protected] (EBH), [email protected] (JGD), [email protected] (RWS), [email protected] (BGF), [email protected] (AYA), [email protected] (EFMIII), [email protected] (MAMC), [email protected] (RNR) *Corresponding author Received: 6 April 2018 / Accepted: 10 July 2018 / Published online: 31 August 2018 Handling editor: Luis Reino Abstract Summarizing historical records of potentially invasive species increases understanding of propagule pressure, spatiotemporal trends, and establishment risk of these species. We compiled records of non-native pythons and boas from the Florida Keys, cross-referenced them to eliminate duplicates, and categorized each record’s credibility. We report on 159 observations of six python and boa species in the Florida Keys over the past 17 years. -

BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK the Florida Keys Begin with Soldier Key in the Northern Section of the Park and Continue to the South and West

CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND HISTORY GEOLOGY AND PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK The Florida Keys begin with Soldier Key in the northern section of the Park and continue to the south and west. The upper Florida Keys (from Soldier to Big Pine Key) are the remains of a shallow coral patch reef that thrived one hundred thousand or more years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch. The ocean level subsided during the following glacial period, exposing the coral to die in the air and sunlight. The coral was transformed into a stone often called coral rock, but more correctly termed Key Largo limestone. The other limestones of the Florida peninsula are related to the Key Largo; all are basically soft limestones, but with different bases. The nearby Miami oolitic limestone, for example, was formed by the precipitation of calcium carbonate from seawater into tiny oval particles (oolites),2 while farther north along the Florida east coast the coquina of the Anastasia formation was formed around the shells of Pleistocene sea creatures. When the first aboriginal peoples arrived in South Florida approximately 10,000 years ago, Biscayne Bay was a freshwater marsh or lake that extended from the rocky hills of the present- day keys to the ridge that forms the current Florida coast. The retreat of the glaciers brought about a gradual rise in global sea levels and resulted in the inundation of the basin by seawater some 4,000 years ago. Two thousand years later, the rising waters levelled off, leaving the Florida Keys, mainland, and Biscayne Bay with something similar to their current appearance.3 The keys change. -

Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands

Florida’s Wildlife Contingency Plan for Oil Spills – June 2012 Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands This section will contain requirements for specific parks, refuges, management areas, etc. and will be developed by the managers of these facilities. If Special Use Permits are required, the permit should either be attached, or instructions for obtaining permits should be included. Private Property: Do not trespass on private property. If appropriate, ask permission to access the property from the land owner. If permission cannot be obtained to access the property, make a note, record waypoints, and move on to the next portion of the survey. Public Property: The purpose of this section is to identify any special operational considerations for RP contractors/agents searching for and/or recovering oiled wildlife on specific public lands/facilities. Name of Facility: County(ies): Contact(s): [Name/Number/Email] Required Lead Time: Types of Restrictions (see examples below) • Hours of Entry • Required accompaniment • Restricted or sensitive areas • Sensitive species or resources • Historic/cultural issues • Limited or difficult access • Over-flight restrictions • Homeland Security Issues • Permit required? 1 Florida’s Wildlife Contingency Plan for Oil Spills – June 2012 Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands USFWS Contact in Florida USFWS Contacts in Florida Station Name Location Telephone PANAMA CITY ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE PANAMA CITY, FL 850-769-0552 SOUTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE VERO BEACH, FL 772-562-3909 NORTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE JACKSONVILLE, FL 904-731-3336 FLORIDA MIGRATORY BIRD PROGRAM HAVANA, FL 850-539-1684 WELAKA NATIONAL FISH HATCHERY WELAKA, FL 386-467-2374 CHASSAHOWITZKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CRYSTAL RIVER, FL 352-563-2088 CEDAR KEYS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CHIEFLAND, FL 352-493-0238 LOWER SUWANNEE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CHIEFLAND, FL 352-493-0238 J.N. -

SFL-38 Bay Florida Keys 80°30'0"W Map Continued On: SFL-42 National Marine80°22'30"W National Marine Main Sanctuary Sanctuary Key

SFL42-01 XXX FKNMS d SFL-42 Everglades National Park ! !¤ Barnes Sound j[ Short u u Key Florida Keys Geographic Response Plan Map:Manatee SFL-38 Bay Florida Keys 80°30'0"W Map continued on: SFL-42 National Marine80°22'30"W National Marine Main Sanctuary Sanctuary Key 25°15'0"N 1 25°15'0"N ¤£ Manatee Bay u Florida Keys Main National Marine S d Key Sanctuary (!! 250 50 # XXX 00 ][ ! 4 0 SFL38-01 5 i AOR 0 r iam 112 0 M Manatee 1 or Long Sound t Crocodile Lake c 00 Creek Barnes Sound S e 21 e S National Wildlife ct Sector Key # or Refuge M West AOR XXX Sector i # K am u e i A SFL38-02 Long Sound Pass 111 y W ! e O and Shell Creek/Little Florida Keys SFL39-02 s t R d A Blackwater Sound ! National Marine Harrison Tract O R Sanctuary (Bay Side) 0 0 AB5 2 Little Blackwater 00 Sound 13 110 0 ! 125 Key 0 0 00 Map continued on:SFL-39 10 XXX # 13 650 Snipe Point Jewfish Largo Blackwater Pass SFL38-03 109 XXX Creek Blackwater Pass ! and Railroad # SFL38-04 Jewfish 108 ! Creek ¡[ Lake Duck Surprise Key j SFL38-06 !(S d 1000 ! The Boggies Crocodiles Area - ! 13 107 Map continued on:SFL-37 Everglades 00 0 Blackwater Sound 5 9 National 9 10 00 d 50 50 ! Rattlesnake Park 10 Blackwater XXX # S Key Sound ][ 1500 !( 106 0 XXX XXX u ! 60 !¤ FKNMS d Florida SFL38-05 !(h ! N.