Pioneering on Elliott Key: 1934-1935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collier Miami-Dade Palm Beach Hendry Broward Glades St

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission F L O R ID A 'S T U R N P IK E er iv R ee m Lakewood Park m !( si is O K L D INDRIO ROAD INDRIO RD D H I N COUNTY BCHS Y X I L A I E O W L H H O W G Y R I D H UCIE BLVD ST L / S FT PRCE ILT SRA N [h G Fort Pierce Inlet E 4 F N [h I 8 F AVE "Q" [h [h A K A V R PELICAN YACHT CLUB D E . FORT PIERCE CITY MARINA [h NGE AVE . OKEECHOBEE RA D O KISSIMMEE RIVER PUA NE 224 ST / CR 68 D R !( A D Fort Pierce E RD. OS O H PIC R V R T I L A N N A M T E W S H N T A E 3 O 9 K C A R-6 A 8 O / 1 N K 0 N C 6 W C W R 6 - HICKORY HAMMOCK WMA - K O R S 1 R L S 6 R N A E 0 E Lake T B P U Y H D A K D R is R /NW 160TH E si 68 ST. O m R H C A me MIDWAY RD. e D Ri Jernigans Pond Palm Lake FMA ver HUTCHINSON ISL . O VE S A t C . T I IA EASY S N E N L I u D A N.E. 120 ST G c I N R i A I e D South N U R V R S R iv I 9 I V 8 FLOR e V ESTA DR r E ST. -

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV. Biscayne National Park By Kenneth G. Rice1, J. Hardin Waddle1, Marquette E. Crockett 2, Christopher D. Bugbee2, Brian M. Jeffery 2, and H. Franklin Percival 3 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Florida Integrated Science Center 2 University of Florida, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation 3 Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Open-File Report 2007-1057 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Rice, K.G., Waddle, J.H., Crockett, M.E., Bugbee, C.D., Jeffery, B.M., and Percival, H.F., 2007, Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume IV. Biscayne National Park: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2007-1057, 65 p. Online at: http://pubs.usgs.gov/ofr/2007/1057/ For more information about this report, contact: Dr. Kenneth G. Rice U.S. Geological Survey Florida Integrated Science Center UF-FLREC 3205 College Ave. Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33314 USA E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 954-577-6305 Fax: 954-577-6347 Dr. -

Report SFRC-83/01 Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity

Report SFRC-83/01 Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity NATIONAL b lb -a'*? m ..-.. # .* , *- ,... - . ,--.-,, , . LG LG - m,*.,*,*, Or 7°C ,"7cn,a. Q*Everglades National Park, South Florida Research Center, P.O.Box 279, Homestead, Florida 33030 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ........................... 1 STUDYAREA ............................ 1 METHODS .............................. 3 RESULTS .............................. 4 Figure 1. Distribution of the indigo snake in southern Florida ..... 5 Figure 2 . Distribution of the indigo snake in the Florida Keys including Biscayne National Park ............. 6 DISCUSSION ............................. 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................ 13 LITERATURE CITED ......................... 14 APPENDIX 1. Observations of indigo snakes in southern Florida ....... 17 APPENDIX 2 . Data on indigo snakes examined in and adjacent to Everglades National Park ................. 24 APPENDIX 3. Museum specimens of indigo snakes from southern Florida ... 25 4' . Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity Report ~F~~-83/01 Todd M. Steiner, Oron L. Bass, Jr., and James A. Kushlan National Park Service South Florida Research Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida 33030 January 1983 Steiner, Todd M., Oron L. Bass, Jr., and James A. Kushlan. 1983. Status of the Eastern Indigo Snake in Southern Florida National Parks and Vicinity. South Florida Research Center Report SFRC- 83/01. 25 pp. INTRODUCTION The status and biology of the eastern indigo snake, Drymarchon corais couperi, the largest North American snake (~awler,1977), is poorly understood. Destruction of habitat and exploitation by the pet trade have reduced its population levels in various localities to the point that it is listed by the Federal government as a threatened species. -

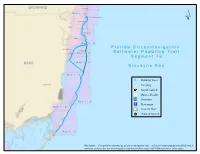

Segment 16 Map Book

Hollywood BROWARD Hallandale M aa p 44 -- B North Miami Beach North Miami Hialeah Miami Beach Miami M aa p 44 -- B South Miami F ll o r ii d a C ii r c u m n a v ii g a tt ii o n Key Biscayne Coral Gables M aa p 33 -- B S a ll tt w a tt e r P a d d ll ii n g T r a ii ll S e g m e n tt 1 6 DADE M aa p 33 -- A B ii s c a y n e B a y M aa p 22 -- B Drinking Water Homestead Camping Kayak Launch Shower Facility Restroom M aa p 22 -- A Restaurant M aa p 11 -- B Grocery Store Point of Interest M aa p 11 -- A Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment 16: Biscayne Bay Little Pumpkin Creek Map 1 B Pumpkin Key Card Point Little Angelfish Creek C A Snapper Point R Card Sound D 12 S O 6 U 3 N 6 6 18 D R Dispatch Creek D 12 Biscayne Bay Aquatic Preserve 3 ´ Ocean Reef Harbor 12 Wednesday Point 12 Card Point Cut 12 Card Bank 12 5 18 0 9 6 3 R C New Mahogany Hammock State Botanical Site 12 6 Cormorant Point Crocodile Lake CR- 905A 12 6 Key Largo Hammock Botanical State Park Mosquito Creek Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge Dynamite Docks 3 6 18 6 North Key Largo 12 30 Steamboat Creek John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park Carysfort Yacht Harbor 18 12 D R D 3 N U O S 12 D R A 12 C 18 Basin Hills Elizabeth, Point 3 12 12 12 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 3 6 12 12 3 12 6 12 Segment 16: Biscayne Bay 3 6 Map 1 A 12 12 3 6 ´ Thursday Point Largo Point 6 Mary, Point 12 D R 6 D N U 3 O S D R S A R C John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park 5 18 3 12 B Garden Cove Campsite Snake Point Garden Cove Upper Sound Point 6 Sexton Cove 18 Rattlesnake Key Stellrecht Point Key Largo 3 Sound Point T A Y L 12 O 3 R 18 D Whitmore Bight Y R W H S A 18 E S Anglers Park R 18 E V O Willie, Point Largo Sound N: 25.1248 | W: -80.4042 op t[ D A I* R A John Pennekamp State Park A M 12 B N: 25.1730 | W: -80.3654 t[ O L 0 Radabo0b. -

Pseudophoenix Sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park

Status update: Long-term monitoring of Sargent’s cherry palm (Pseudophoenix sargentii) on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park FEBRUARY 2021 Acknowledgments Thank you to Biscayne National Park for more than three decades of support for this collaborative project on Pseudophoenix sargentii augmentation and demographic monitoring. Monitoring in 2021 was funded by the Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, under Agreement #027132. For assistance with field work and logistics we would like to thank Morgan Wagner, Michael Hoffman, Brian Lockwood, Shelby Moneysmith, Vanessa McDonough, and Astrid Santini from Biscayne National Park, Eliza Gonzalez from Montgomery Botanical Center, Dallas Hazelton from Miami-Dade County, and volunteer biologists Joseph Montes de Oca and Elizabeth Wu. Thank you to the cooperators whose excellent past work on this project has laid the foundation upon which we stand today, especially Carol Lippincott, Rob Campbell, Joyce Maschinski, Janice Duquesnel, Dena Garvue, and Sam Wright. Janice Duquesnel provided important details about the 1991-1994 outplanting efforts. Suggested citation Possley, J., J. Lange, S. Wintergerst and L. Cuni. 2021. Status update: long-term monitoring of Pseudophoenix sargentii on Elliott Key, Biscayne National Park. Unpublished report from Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, funded by Florida Dept. of Agriculture and Consumer Services Agreement #027132. Background Pseudophoenix sargentii H.Wendl. ex Sarg., known by the common names ‘Sargent’s cherry palm’ and ‘buccaneer palm,’ is a slow-growing palm native to coastal habitats throughout the Caribbean basin, where it grows on exposed limestone or in humus or sand over limestone. Over the past century, the species has declined throughout its range, due to in part to overharvesting for use in landscaping. -

Florida Coral Reefs: Islandia

FOREWORD· In their present relatively undeveloped state, the upper Florida Keys and the adjoining waters and submerged. lands of Biscayne ~ay and the Atlantic Ocean are an enviromr~.ental element highly important to Florida ancl a valuable recreation resource for the nation. Fully aware that intensive private development would greatly alter . these values, the Secretary of the Interior directed the National Park Service and the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, assisted by the Fish and Wildlife Service, to conduct studies of the area. This interim professional report is the r~sult of these studies. It is being distributed now to solicit the comments and suggestions of interested parties. The additional information obtained in this manner will be utilized by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Outdoor Recre ation to complete the study and formulate recommendations to the Secretary· of the Interior. It is requested that comments and suggestions on this interim profes sional report be sent to the Regional Director, Southeast Region, Na tional Park Service, P. 0. Box 10008, Richmond, Virginia 23240. Material should be submitted in time to reach the Regional Director on or before August 15, 1965. ~~ Edward C. Crafts Director Director Bureau of Outdoor Recreation National Park Service Page No. FOREWORD THE STUDY 2 THE CORAL REEFS The Resource 3 The Climate 5 The Ecology 6 MAN AND THE CORAL REEFS 10 THE SITUATION Development Possibilities · 12 Significance for Preservation 12 THE OPPORTUNITIES 18 Alternative Plans 14' Plan 1 16 Plan 2 20 Plan 3 24 THE STUDY In response to interest expressed by the weekending, and vacationing are engaged Dade Co1:-1nty Board of Commissioners and in extensively. -

Biscayne National Park, Florida

National Park Service Biscayne U.S. Department of the Interior Camping Guide to Biscayne National Park Boca Chita Key Tent camping is permitted in designated areas on Elliott and Boca Chita Keys. These islands are accessible by boat only. Camping is limited to fourteen (14) consecutive days or no more than thirty (30) days within a calendar year. Reservations are not accepted. The sites are available on a first-come, first-served basis. No services are available on the islands. Facilities Elliott Key: Freshwater toilets, cold water showers, and drinking water are available. Boca Chita Key: Saltwater toilets are available. Sinks, showers and drinking water are NOT available. Fees There is a $15 per night per campsite camping fee. The fee includes a standard campsite (up to 6 people and 2 tents). If docking a boat overnight, there is a $20 fee that includes one night camping. Group campsites (30 people and 5 tents) are $30 per night on Elliott Key. Group campsite is available by reservation only (305) 230-1144 x 008. Holders of the Interagency Senior or Access passes receive a 50% discount on camping and marina use fees. The fee is paid at the self- service fee station on each island. It is your responsibility to make sure that your fees are paid. NPS rangers will verify payment compliance. Camping/marina use fees must be paid PRIOR to 5 p.m. daily. Anyone who arrives after 5 p.m. must pay camping/ marina use fees immediately upon arrival. Any vessel in the harbor after 5 p.m. -

Intracoastal Waterway Miami to Elliott

BookletChart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Miami to Elliott Key NOAA Chart 11465 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the Biscayne Channel leads through the shoals south of Cape Florida into Biscayne Bay. It is partially dredged, but the channel has shoaled. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration channel is marked by lights and daybeacons. Craft whose draft is close National Ocean Service to the limiting depth of the channel should exercise extreme caution in Office of Coast Survey navigating it. Several channels leading through the shoals between Biscayne Channel and Key Biscayne are used by local boats. www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Cape Florida Anchorage, with depths of 12 to 20 feet, is about 300 yards 888-990-NOAA westward of the south end of Cape Florida with the lighthouse tower bearing northward of 069°. This is a poor anchorage with southerly What are Nautical Charts? winds. Miami South Channel is a dredged cut leading from Biscayne Bay, Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show westward of Virginia Key, to the Miami waterfront. One branch of it water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much leads into the Miami River, and the other leads directly to the basin more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and off Bay Front Park. The Intracoastal Waterway southward to Key West efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial passes through Miami South Channel. Clearance of the Rickenbacker ships that carry America’s commerce. -

A Comprehensive Assessment of Python and Boa Reports from the Florida Keys

Management of Biological Invasions (2018) Volume 9, Issue 3: 369–377 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2018.9.3.18 Open Access © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC Research Article Exotic predators may threaten another island ecosystem: A comprehensive assessment of python and boa reports from the Florida Keys Emma B. Hanslowe1,4,*, James G. Duquesnel1, Ray W. Snow2, Bryan G. Falk1,2, Amy A. Yackel Adams1, Edward F. Metzger III3, Michelle A.M. Collier2 and Robert N. Reed1 1U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Avenue, Building C, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526, USA 2South Florida Natural Resources Center, Everglades National Park, 40001 State Road 9336, Homestead, Florida 33034, USA 3Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center, University of Florida, 3205 College Avenue, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 33314, USA 4Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology, Colorado State University, 1417 Campus Delivery, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, USA Author e-mails: [email protected] (EBH), [email protected] (JGD), [email protected] (RWS), [email protected] (BGF), [email protected] (AYA), [email protected] (EFMIII), [email protected] (MAMC), [email protected] (RNR) *Corresponding author Received: 6 April 2018 / Accepted: 10 July 2018 / Published online: 31 August 2018 Handling editor: Luis Reino Abstract Summarizing historical records of potentially invasive species increases understanding of propagule pressure, spatiotemporal trends, and establishment risk of these species. We compiled records of non-native pythons and boas from the Florida Keys, cross-referenced them to eliminate duplicates, and categorized each record’s credibility. We report on 159 observations of six python and boa species in the Florida Keys over the past 17 years. -

BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK the Florida Keys Begin with Soldier Key in the Northern Section of the Park and Continue to the South and West

CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND HISTORY GEOLOGY AND PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY OF BISCAYNE NATIONAL PARK The Florida Keys begin with Soldier Key in the northern section of the Park and continue to the south and west. The upper Florida Keys (from Soldier to Big Pine Key) are the remains of a shallow coral patch reef that thrived one hundred thousand or more years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch. The ocean level subsided during the following glacial period, exposing the coral to die in the air and sunlight. The coral was transformed into a stone often called coral rock, but more correctly termed Key Largo limestone. The other limestones of the Florida peninsula are related to the Key Largo; all are basically soft limestones, but with different bases. The nearby Miami oolitic limestone, for example, was formed by the precipitation of calcium carbonate from seawater into tiny oval particles (oolites),2 while farther north along the Florida east coast the coquina of the Anastasia formation was formed around the shells of Pleistocene sea creatures. When the first aboriginal peoples arrived in South Florida approximately 10,000 years ago, Biscayne Bay was a freshwater marsh or lake that extended from the rocky hills of the present- day keys to the ridge that forms the current Florida coast. The retreat of the glaciers brought about a gradual rise in global sea levels and resulted in the inundation of the basin by seawater some 4,000 years ago. Two thousand years later, the rising waters levelled off, leaving the Florida Keys, mainland, and Biscayne Bay with something similar to their current appearance.3 The keys change. -

Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands

Florida’s Wildlife Contingency Plan for Oil Spills – June 2012 Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands This section will contain requirements for specific parks, refuges, management areas, etc. and will be developed by the managers of these facilities. If Special Use Permits are required, the permit should either be attached, or instructions for obtaining permits should be included. Private Property: Do not trespass on private property. If appropriate, ask permission to access the property from the land owner. If permission cannot be obtained to access the property, make a note, record waypoints, and move on to the next portion of the survey. Public Property: The purpose of this section is to identify any special operational considerations for RP contractors/agents searching for and/or recovering oiled wildlife on specific public lands/facilities. Name of Facility: County(ies): Contact(s): [Name/Number/Email] Required Lead Time: Types of Restrictions (see examples below) • Hours of Entry • Required accompaniment • Restricted or sensitive areas • Sensitive species or resources • Historic/cultural issues • Limited or difficult access • Over-flight restrictions • Homeland Security Issues • Permit required? 1 Florida’s Wildlife Contingency Plan for Oil Spills – June 2012 Special Conditions for Access to Public and Private Lands USFWS Contact in Florida USFWS Contacts in Florida Station Name Location Telephone PANAMA CITY ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE PANAMA CITY, FL 850-769-0552 SOUTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE VERO BEACH, FL 772-562-3909 NORTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES FIELD OFFICE JACKSONVILLE, FL 904-731-3336 FLORIDA MIGRATORY BIRD PROGRAM HAVANA, FL 850-539-1684 WELAKA NATIONAL FISH HATCHERY WELAKA, FL 386-467-2374 CHASSAHOWITZKA NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CRYSTAL RIVER, FL 352-563-2088 CEDAR KEYS NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CHIEFLAND, FL 352-493-0238 LOWER SUWANNEE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE CHIEFLAND, FL 352-493-0238 J.N. -

SFL-38 Bay Florida Keys 80°30'0"W Map Continued On: SFL-42 National Marine80°22'30"W National Marine Main Sanctuary Sanctuary Key

SFL42-01 XXX FKNMS d SFL-42 Everglades National Park ! !¤ Barnes Sound j[ Short u u Key Florida Keys Geographic Response Plan Map:Manatee SFL-38 Bay Florida Keys 80°30'0"W Map continued on: SFL-42 National Marine80°22'30"W National Marine Main Sanctuary Sanctuary Key 25°15'0"N 1 25°15'0"N ¤£ Manatee Bay u Florida Keys Main National Marine S d Key Sanctuary (!! 250 50 # XXX 00 ][ ! 4 0 SFL38-01 5 i AOR 0 r iam 112 0 M Manatee 1 or Long Sound t Crocodile Lake c 00 Creek Barnes Sound S e 21 e S National Wildlife ct Sector Key # or Refuge M West AOR XXX Sector i # K am u e i A SFL38-02 Long Sound Pass 111 y W ! e O and Shell Creek/Little Florida Keys SFL39-02 s t R d A Blackwater Sound ! National Marine Harrison Tract O R Sanctuary (Bay Side) 0 0 AB5 2 Little Blackwater 00 Sound 13 110 0 ! 125 Key 0 0 00 Map continued on:SFL-39 10 XXX # 13 650 Snipe Point Jewfish Largo Blackwater Pass SFL38-03 109 XXX Creek Blackwater Pass ! and Railroad # SFL38-04 Jewfish 108 ! Creek ¡[ Lake Duck Surprise Key j SFL38-06 !(S d 1000 ! The Boggies Crocodiles Area - ! 13 107 Map continued on:SFL-37 Everglades 00 0 Blackwater Sound 5 9 National 9 10 00 d 50 50 ! Rattlesnake Park 10 Blackwater XXX # S Key Sound ][ 1500 !( 106 0 XXX XXX u ! 60 !¤ FKNMS d Florida SFL38-05 !(h ! N.