History of Scotts Bluff National Monument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Gering Courier Building, Constructed in 1915, Was the Third Building to House the Publishing Business of Pioneer Newspaperman, A

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name Gering Courier Building Other names/site number SF01-017 2. Location Street & number 1428 10th Street Not for publication [ ] City or town Gering Vicinity [ ] State Nebraska Code NE County Scotts Bluff Code 157 Zip code 69341 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination [] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [x] meets [] does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [] nationally [x] statewide [] locally. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Scotts Bluff National Monument AND/OR COMMON

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE 1NTL:RIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTQRIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ! SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Scotts Bluff National Monument AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Three miles west of Gering on Nebraska 92 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Gering •X-. VICINITY OF Third STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Nebraska 31 Scotts Bluff 157 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT 2LPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL 2LPARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE X-SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) Midwest Regional Office.. National Park Service STREET & NUMBER 1709 Jackson Street CITY, TOWN Omaha VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Midwest Regional Office, National Park Service STREET & NUMBER 1709 Jackson Street CITY, TOWN STATE Omaha Nebraska TITLE National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1957-61 ^.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qffi ce o f Archeology and Historic Preservation, National Park CITY, TOWN ~ STATE Service Washington B.C. Form No. 10-301a ieev,1Q-7>) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PROPERTY PHOTOGRAPH FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ^^^^^..^^^ _____ TYPE ALL ENTRIES ENCLOSE WITH PHOTOGRAPH NAME . HISTORIC . Scotts Bluff National Monument AND/OR COMMON LOCATION CITY, TOWN Gering _X_VICINITYOF COUNTY Scotts Bluff STATE Nebraska PHOTO REFERENCE , . -

Nebraska Statewide Preservation Plan 2017-2021

State Historic BUILDING ON THE Preservation Plan for the State of Nebraska, FUTURE OF OUR PAST 2017-2021 This plan sets forth our goals and objectives for Preservation for the state of Nebraska for the next five years. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 2 Chapter 1: Public Participation Process 3 Chapter 2: Summary of Current Knowledge of Nebraska Historical Periods 11 Chapter 3: A Vision of Preservation in Nebraska 19 Chapter 4: A Five-Year Vision for Historic Preservation in Nebraska 29 Bibliography 33 Appendix 1 Questions from the Nebraska State Historic Preservation Plan Survey 35 Appendix 2 List of National Register Properties listed between 2012-2016 38 Appendix 3 List of National Historic Landmarks in Nebraska 40 Appendix 4 Glossary 41 Appendix 5 Map of Nebraska Certified Local Governments 44 2 Executive Summary Every five years, the Nebraska State Historic Preservation Office (NeSHPO), a division of History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society), prepares a statewide preservation plan that provides a set of goals regarding preservation for the entire state. This plan sets forth goals and objectives for Preservation for the state of Nebraska for the next five years. In developing this plan, we engaged with the people of Nebraska to learn about their objectives and opportunities for preservation in their communities. This plan seeks to create a new vision for the future and set goals that will address the needs of stakeholders and ensure the support, use and protection of Nebraska’s historic resources. VISION The Nebraska State Historic Preservation Office seeks to understand the historic and cultural resources that encompass aspects of our state’s history to evaluate the programs, preservation partnerships and state and federal legislation that can be used to preserve these resources and their relative successes and failures. -

Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska

Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska (Version IV – March 9, 2010) By Steven B. Rolfsmeier Kansas State University Herbarium Manhattan, KS 66506 and Gerry Steinauer Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Aurora, NE 68818 A publication of the NEBRASKA NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION LINCOLN, NEBRASKA 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction..................................................................................… 1 Terrestrial Ecological System Classification…...................................................... 1 Ecological System Descriptions…………............................................................. 2 Terrestrial Natural Community Classification……………………………….….. 3 Vegetation Hierarchy………………………….………………………………… 4 Natural Community Nomenclature............................................................…........ 5 Natural Community Ranking..;……………….……….....................................…. 6 Natural Community Descriptions………….......................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Ecological Systems of Nebraska.………………………………… 10 Upland Forest, Woodland, and Shrubland Systems…………………………….. 10 Eastern Upland Oak Bluff Forest……….……………………………….. 10 Eastern Dry-Mesic Bur Oak Forest and Woodland……………………… 12 Great Plains Dry Upland Bur Oak Woodland…………………………… 15 Great Plains Wooded Draw, Ravine and Canyon……………………….. 17 Northwestern Great Plains Pine Woodland……………………………… 20 Upland Herbaceous Systems…………………………………………………….. 23 Central Tall-grass Prairie……………………………………………….. -

Nebraska Platte-Republican Resources Area Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP)

FINAL Programmatic Environmental Assessment Nebraska Platte-Republican Resources Area Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) Farm Service Agency United States Department of Agriculture March 2005 2005 NPRRA CREP Cover Sheet Final Programmatic Environmental Assessment Cover Sheet Mandated Action: The United States Department of Agriculture, Commodity Credit Corporation (USDA/CCC) and the State of Nebraska have agreed to implement the Nebraska Platte-Republican Resources Area (NPRRA) Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), a component of the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). USDA is provided the statutory authority by the provisions of the Food Security Act of 1985, as amended (16 U.S.C. 3830 et seq.), and the regulations at 7 CFR 1410. In accordance with the 1985 Act, USDA/CCC is authorized to enroll lands through December 31, 2007. The Farm Service Agency (FSA) of USDA proposes to enter into a CREP agreement with the State of Nebraska. CREP is a voluntary land conservation program for State agricultural landowners. Type of Document: Programmatic Environmental Assessment (PEA) Lead Agency: United States Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency Sponsoring Agencies: Nebraska State Department of Agriculture and Markets; Nebraska State Department of Environmental Conservation; Nebraska State Soil and Water Conservation Committee Cooperating Agencies: United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS); Soil & Water Conservation Districts in Nebraska State; Cornell Cooperative Extension Associations For Further Information: Paul Cernik, Farm Loan Specialist Farm Service Agency 7131 A Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Phone: (402) 437-5886 Fax: (402) 437-5418 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ne.nrcs.usda.gov/ Gregory J. Reisdorff Lincoln FSA State Office 7131 A ST Lincoln, NE 68510-4202 State Office Phone: (402) 437-5581 Phone: (402) 437-5456 E-mail: [email protected] iii 2005 NPRRA CREP Cover Sheet Final Programmatic Environmental Assessment Lavaine M. -

Geology and Ground-Water Resources of Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR J. A. Krug, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 943 GEOLOGY AND GROUND-WATER RESOURCES OF SCOTTS BLUFF COUNTY, NEBRASKA BY L. K. WENZEL, R. C. CADY AND H. A. WAITE Prepared in cooperation with the CONSERVATION AND SURVEY DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBJRASKA ;\w UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1946 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. 8. Government Printing Office, Washington 86, D. C. Price 25 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................................. 1 History, scope, and purpose of the investigation........................................................ 2 Geography of Scotts Bluff County.................................................................................. 5 Location..... ..... ................. ................................................................................... 5 Area and population.................................................................................................... 5 Agriculture...-.......................................:......................................................................... 5 Manufacturing................................................................................................................ 6 Transportation .................................................................... .. .. .................... 6 History................................................................................................................................... -

Scotts Bluff U.S

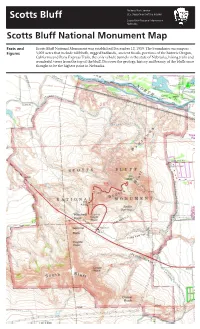

National Park Service Scotts Bluff U.S. Department of the Interior Scotts Bluff National Monument Nebraska Scotts Bluff National Monument Map Facts and Scotts Bluff National Monument was established December 12, 1919. The boundaries encompass Figures 3,003 acres that include tall bluffs, rugged badlands, ancient fossils, portions of the historic Oregon, California and Pony Express Trails, the only vehicle tunnels in the state of Nebraska, hiking trails and wonderful views from the top of the bluff. Discover the geology, history and beauty of the bluffs once thought to be the highest point in Nebraska. Oregon Trail Saddle Rock Trail Prairie View Trail Old Oregon Trail Road Hiking Trails The hiking trails at Scotts Bluff National Monument are open sunrise to sunset year round. The at the maintained trails on and around Scotts Bluff are easy to follow as most are paved. Hiking on South Monument Bluff is cross-country as there are no designated trails. Pets are allowed on a leash. Climbing on any of the named rocks is dangerous and closed to the public. Length Level of Trail Name one-way Surface Activity Special Notes Saddle Rock Trail 1.67 mi Asphalt Strenuous 435 ft (132 m) elevation gain; (2.6 km) walk through a short tunnel; views to the east and north Oregon Trail .57 mi Asphalt, Moderate Walk the original Oregon, Cali- (.92 km) dirt fornia and Pony Express Trail; visit the covered wagons and William Henry Jackson’s 1866 campsite Prairie View Trail 1.18 mi Asphalt Moderate Only trail that allows bicycles; (1.89 km) connects to the Monument Path- ways Trail in town North Overlook .74 mi Asphalt Easy to Great views of the river, badlands, (1.19 km) moderate city of Scottsbluff South Overlook .15 mi Asphalt Easy Great views of Mitchell Pass, (.24 km) South Bluff, city of Gering Historic 17 Sites in the 11 Area 8 1 9 6 10 12 7 Scotts Bluff NM 14 16 15 5 13 18 3 2 4 1. -

National Historic Trails Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide

National Trails System National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Historic Trails Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide Nebraska and Northeastern Colorado “Approaching Chimney Rock” By William Henry Jackson Chimney Rock, in western Nebraska, was one of the most notable landmarks recorded in emigrant diaries and journals. Photograph is courtesy of The Wagner Perspective. NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAILS AUTO TOUR ROUTE INTERPRETIVE GUIDE Nebraska and Northeastern Colorado Prepared by National Park Service National Trails System—Intermountain Region 324 South State Street, Suite 200 Box 30 Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 Telephone: 801-741-1012 www.nps.gov/cali www.nps.gov/oreg www.nps.gov/mopi www.nps.gov/poex NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR August 2006 Contents Introduction • • • • • • • 1 The Great Platte River Road • • • • • • • 2 From Path to Highway • • • • • • • 4 “A Whiz and a Hail” — The Pony Express • • • • • 8 A “Frayed Rope” • • • • • • • 11 The Platte Experience • • • • • • • 15 Natives and Newcomers: A Gathering Storm • • • • • • • 18 War on the Oregon & California Trails • • • • • • • 21 Corridor to Destiny • • • • • • • 24 SITES AND POINTS OF INTEREST • • • • • • • 25 Auto Tour Segment A: Odell to Kearney • • • • • • • 26 Auto Tour Segment B: Omaha-Central City-Kearney • • • • • • 35 Auto Tour Segment C: Nebraska City-Central City-Kearney • • • • • • • 41 Auto Tour Segment D: Kearney to Wyoming Border • • • • • • • 43 For More Information • • • • • • • 61 Regional Map • • • • • • • inside the back cover Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide Nebraska IntroductIon any of the pioneer trails and other Mhistoric routes that are important in our nation’s past have been designated by Auto Tour Congress as National Historic Trails. While most of those old roads and routes are Route not open to motorized traffic, people can drive along modern highways that lie close to the original trails. -

Foundation Document Overview, Scotts Bluff

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Scotts Bluff National Monument Nebraska Contact Information For more information about the Scotts Bluff National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 308-436-9700 or write to: Superintendent, Scotts Bluff National Monument PO Box 27 Gering NE 69341-0027 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Scotts Bluff National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit and are supported by data, research, and consensus. The following significance statements have been identified for Scotts Bluff National Monument. (Please note that the sequence of the statements does not reflect the level of significance.) 1. Historic Trail Corridors – The Overland Trail ruts through Mitchell Pass at Scotts Bluff are the remnants of one of humankind’s most epic migrations to America’s western frontier. 2. Landmark – Scotts Bluff was a physical and emotional The purpose of Scotts Bluff National landmark for emigrants and had cultural significance Monument is to preserve the to American Indians. Views to and from this landmark scenic, scientific, geologic, and were critical for pioneers traveling west. historic integrity of Scotts Bluff. The 3. Topography and Trail History – The land formations monument preserves remnants of the of the area influenced the locations of historic trails, Oregon Trail through Mitchell Pass which evolved from the time of the earliest plains inhabitants 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. -

Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan July 2021 Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan FOR THE COUNTIES OF BANNER, CHEYENNE, KIMBALL, MORRILL, AND SCOTTS BLUFF, NEBRASKA Photo courtesy of Justin Powell July 2021 Update Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan Map 1: Overview of the Wildcat Hills CWPP Region and fire districts located all or partly within it. ii Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan July 2021 Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan FACILITATED BY THE Nebraska Forest Service IN COLLABORATION AND COOPERATION WITH B ANNER, CHEYENNE, KIMBALL, MORRILL, AND SCOTTS BLUFF COUNTIES LOCAL VOLUNTEER FIRE DISTRICTS EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT REGIONS 2 1 AND 22 LOCAL MUNICIPAL OFFICIALS LOCAL, STATE, AND FEDERAL NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCIES AREA LANDOWNERS Prepared by Sandy Benson Forest Fuels Management Specialist and Community Wildfire Protection Plan Coordinator Nebraska Forest Service Phone 402-684-2290 • [email protected] http://nfs.unl.edu Photo courtesy of Nathan Flowers It is the policy of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln not to discriminate based upon age, race, ethnicity, color, national origin, gender, sex, pregnancy, disability, sexual orientation, genetic information, veteran’s status, marital status, religion or political affiliation. Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan July 2021 iii Wildcat Hills Region Community Wildfire Protection Plan Approved By: Banner County Board of Commissioners Signature: ____________ Title: ___________ Name _____________issioners Date: __________ _ ������...::...;::....:..:::::.=-.....::._