Local Places, National Spaces: Public Memory, Community Identity, and Landscape at Scotts Bluff National Monument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

History of Scotts Bluff National Monument

History of Scotts Bluff National Monument History of Scotts Bluff National Monument History of Scotts Bluff National Monument Earl R. Harris ©1962, Oregon Trail Museum Association CONTENTS NEXT >>> History of Scotts Bluff National Monument ©1962, Oregon Trail Museum Association history/index.htm — 26-Jan-2003 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/scbl/history/index.htm[7/2/2012 3:30:26 PM] History of Scotts Bluff National Monument http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/scbl/history/index.htm[7/2/2012 3:30:26 PM] History of Scotts Bluff National Monument (Contents) History of Scotts Bluff National Monument Contents Cover Foreword Geographical Setting Prehistory of the Area Prehistoric Man The Coming of the White Man Migration to the West Settlement Period The National Park Movement Custodian Maupin Custodian Mathers Era of Development Custodian Cook Custodian Randels Custodian Mattes Custodian Budlong Superintendent Anderson Mission 66 Superintendent Henneberger Appendix A: Enabling Legislation Appendix B: Annual Visitation (1936-1961) http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/scbl/history/contents.htm[7/2/2012 3:30:27 PM] History of Scotts Bluff National Monument (Contents) Appendix C: Custodians and Superintendents Appendix D: Staff Bibliography References Copyright © 1962 by the Oregon Trail Museum Association Gering, Nebraska About the Author Earl R. Harris is a native of New Brighton, Pennsylvania, where he attended public schools. In 1945 he moved to Deadwood, Souuth Dakota, and later attended Black Hills Teachers College. He is a veteran of the Korean conflict and was a professional musician for four years before becoming associated with the National Park Service, in 1953, at Mount Rushmore National Memorial, South Dakota. -

Scotts Bluff National Monument AND/OR COMMON

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE 1NTL:RIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTQRIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES ! SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC Scotts Bluff National Monument AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Three miles west of Gering on Nebraska 92 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Gering •X-. VICINITY OF Third STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Nebraska 31 Scotts Bluff 157 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT 2LPUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL 2LPARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE X-SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) Midwest Regional Office.. National Park Service STREET & NUMBER 1709 Jackson Street CITY, TOWN Omaha VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Midwest Regional Office, National Park Service STREET & NUMBER 1709 Jackson Street CITY, TOWN STATE Omaha Nebraska TITLE National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings DATE 1957-61 ^.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Qffi ce o f Archeology and Historic Preservation, National Park CITY, TOWN ~ STATE Service Washington B.C. Form No. 10-301a ieev,1Q-7>) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PROPERTY PHOTOGRAPH FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ^^^^^..^^^ _____ TYPE ALL ENTRIES ENCLOSE WITH PHOTOGRAPH NAME . HISTORIC . Scotts Bluff National Monument AND/OR COMMON LOCATION CITY, TOWN Gering _X_VICINITYOF COUNTY Scotts Bluff STATE Nebraska PHOTO REFERENCE , . -

Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska

Terrestrial Ecological Systems and Natural Communities of Nebraska (Version IV – March 9, 2010) By Steven B. Rolfsmeier Kansas State University Herbarium Manhattan, KS 66506 and Gerry Steinauer Nebraska Game and Parks Commission Aurora, NE 68818 A publication of the NEBRASKA NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM NEBRASKA GAME AND PARKS COMMISSION LINCOLN, NEBRASKA 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction..................................................................................… 1 Terrestrial Ecological System Classification…...................................................... 1 Ecological System Descriptions…………............................................................. 2 Terrestrial Natural Community Classification……………………………….….. 3 Vegetation Hierarchy………………………….………………………………… 4 Natural Community Nomenclature............................................................…........ 5 Natural Community Ranking..;……………….……….....................................…. 6 Natural Community Descriptions………….......................................................... 8 Chapter 2: Ecological Systems of Nebraska.………………………………… 10 Upland Forest, Woodland, and Shrubland Systems…………………………….. 10 Eastern Upland Oak Bluff Forest……….……………………………….. 10 Eastern Dry-Mesic Bur Oak Forest and Woodland……………………… 12 Great Plains Dry Upland Bur Oak Woodland…………………………… 15 Great Plains Wooded Draw, Ravine and Canyon……………………….. 17 Northwestern Great Plains Pine Woodland……………………………… 20 Upland Herbaceous Systems…………………………………………………….. 23 Central Tall-grass Prairie……………………………………………….. -

Geology and Ground-Water Resources of Scotts Bluff County, Nebraska

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR J. A. Krug, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director Water-Supply Paper 943 GEOLOGY AND GROUND-WATER RESOURCES OF SCOTTS BLUFF COUNTY, NEBRASKA BY L. K. WENZEL, R. C. CADY AND H. A. WAITE Prepared in cooperation with the CONSERVATION AND SURVEY DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBJRASKA ;\w UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1946 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. 8. Government Printing Office, Washington 86, D. C. Price 25 cents CONTENTS Page Abstract.................................................................................................................................. 1 History, scope, and purpose of the investigation........................................................ 2 Geography of Scotts Bluff County.................................................................................. 5 Location..... ..... ................. ................................................................................... 5 Area and population.................................................................................................... 5 Agriculture...-.......................................:......................................................................... 5 Manufacturing................................................................................................................ 6 Transportation .................................................................... .. .. .................... 6 History................................................................................................................................... -

Scotts Bluff U.S

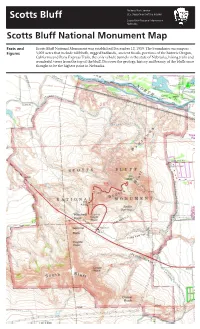

National Park Service Scotts Bluff U.S. Department of the Interior Scotts Bluff National Monument Nebraska Scotts Bluff National Monument Map Facts and Scotts Bluff National Monument was established December 12, 1919. The boundaries encompass Figures 3,003 acres that include tall bluffs, rugged badlands, ancient fossils, portions of the historic Oregon, California and Pony Express Trails, the only vehicle tunnels in the state of Nebraska, hiking trails and wonderful views from the top of the bluff. Discover the geology, history and beauty of the bluffs once thought to be the highest point in Nebraska. Oregon Trail Saddle Rock Trail Prairie View Trail Old Oregon Trail Road Hiking Trails The hiking trails at Scotts Bluff National Monument are open sunrise to sunset year round. The at the maintained trails on and around Scotts Bluff are easy to follow as most are paved. Hiking on South Monument Bluff is cross-country as there are no designated trails. Pets are allowed on a leash. Climbing on any of the named rocks is dangerous and closed to the public. Length Level of Trail Name one-way Surface Activity Special Notes Saddle Rock Trail 1.67 mi Asphalt Strenuous 435 ft (132 m) elevation gain; (2.6 km) walk through a short tunnel; views to the east and north Oregon Trail .57 mi Asphalt, Moderate Walk the original Oregon, Cali- (.92 km) dirt fornia and Pony Express Trail; visit the covered wagons and William Henry Jackson’s 1866 campsite Prairie View Trail 1.18 mi Asphalt Moderate Only trail that allows bicycles; (1.89 km) connects to the Monument Path- ways Trail in town North Overlook .74 mi Asphalt Easy to Great views of the river, badlands, (1.19 km) moderate city of Scottsbluff South Overlook .15 mi Asphalt Easy Great views of Mitchell Pass, (.24 km) South Bluff, city of Gering Historic 17 Sites in the 11 Area 8 1 9 6 10 12 7 Scotts Bluff NM 14 16 15 5 13 18 3 2 4 1. -

National Historic Trails Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide

National Trails System National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Historic Trails Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide Nebraska and Northeastern Colorado “Approaching Chimney Rock” By William Henry Jackson Chimney Rock, in western Nebraska, was one of the most notable landmarks recorded in emigrant diaries and journals. Photograph is courtesy of The Wagner Perspective. NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAILS AUTO TOUR ROUTE INTERPRETIVE GUIDE Nebraska and Northeastern Colorado Prepared by National Park Service National Trails System—Intermountain Region 324 South State Street, Suite 200 Box 30 Salt Lake City, Utah 84111 Telephone: 801-741-1012 www.nps.gov/cali www.nps.gov/oreg www.nps.gov/mopi www.nps.gov/poex NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR August 2006 Contents Introduction • • • • • • • 1 The Great Platte River Road • • • • • • • 2 From Path to Highway • • • • • • • 4 “A Whiz and a Hail” — The Pony Express • • • • • 8 A “Frayed Rope” • • • • • • • 11 The Platte Experience • • • • • • • 15 Natives and Newcomers: A Gathering Storm • • • • • • • 18 War on the Oregon & California Trails • • • • • • • 21 Corridor to Destiny • • • • • • • 24 SITES AND POINTS OF INTEREST • • • • • • • 25 Auto Tour Segment A: Odell to Kearney • • • • • • • 26 Auto Tour Segment B: Omaha-Central City-Kearney • • • • • • 35 Auto Tour Segment C: Nebraska City-Central City-Kearney • • • • • • • 41 Auto Tour Segment D: Kearney to Wyoming Border • • • • • • • 43 For More Information • • • • • • • 61 Regional Map • • • • • • • inside the back cover Auto Tour Route Interpretive Guide Nebraska IntroductIon any of the pioneer trails and other Mhistoric routes that are important in our nation’s past have been designated by Auto Tour Congress as National Historic Trails. While most of those old roads and routes are Route not open to motorized traffic, people can drive along modern highways that lie close to the original trails. -

THE GOLD TREE Thought Leader Crossword Puzzle EDM Without Reflectors 2Nd NCEES Meeting Just for Surveyors Accuracies and Errors » JERRY PENRY, PS

SEPTEMBER 2016 THE GOLD TREE Thought Leader Crossword Puzzle EDM Without Reflectors 2nd NCEES meeting Just for surveyors Accuracies and errors » JERRY PENRY, PS he Wildcat Hills are a scenic area of buttes and evidence that at certain times a military escort accompanied them canyons forested with pine and cedar located in the for protection from the Indians. Fairfield is credited as the surveyor Panhandle region of Nebraska between the North who subdivided T20N-R56W in the late summer of 1873. Platte River and Pumpkin Creek. In the 1830-60’s, On August 19, 1873, while surveying east on a random line at early emigrants passed through the northern region 6.00 chains across the north line of Section 25, Fairfield’s crew of the Wildcat Hills en route to the Pacific Northwest on the reached the western edge of a canyon which offered a magnificent now famous Oregon Trail. Unique sandstone formations rise up view of the country for many miles to the east. Just ahead, near a hundreds of feet above the surrounding landscape. Many promi- small spring fed creek, stood a cedar tree so large that it defied their nent landmarks such as Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock, Scotts imagination. At 33.00 chains, the crew tied in the tree and found it Bluff, and Mitchell Pass were reference points for travelers as they to be 2 chains south of their line. Fairfield stated in his notes that it progressed westward. was the largest cedar tree he had ever seen. The crew measured its The General Land Office surveys in this area commenced in the circumference to be 33 links (21.78’) and scribed upon it Sec. -

Foundation Document Overview, Scotts Bluff

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Scotts Bluff National Monument Nebraska Contact Information For more information about the Scotts Bluff National Monument Foundation Document, contact: [email protected] or 308-436-9700 or write to: Superintendent, Scotts Bluff National Monument PO Box 27 Gering NE 69341-0027 Purpose Significance Significance statements express why Scotts Bluff National Monument resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit and are supported by data, research, and consensus. The following significance statements have been identified for Scotts Bluff National Monument. (Please note that the sequence of the statements does not reflect the level of significance.) 1. Historic Trail Corridors – The Overland Trail ruts through Mitchell Pass at Scotts Bluff are the remnants of one of humankind’s most epic migrations to America’s western frontier. 2. Landmark – Scotts Bluff was a physical and emotional The purpose of Scotts Bluff National landmark for emigrants and had cultural significance Monument is to preserve the to American Indians. Views to and from this landmark scenic, scientific, geologic, and were critical for pioneers traveling west. historic integrity of Scotts Bluff. The 3. Topography and Trail History – The land formations monument preserves remnants of the of the area influenced the locations of historic trails, Oregon Trail through Mitchell Pass which evolved from the time of the earliest plains inhabitants 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. -

Courthouse and Jail Rocks: Landmarks on the Oregon Trail

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Courthouse and Jail Rocks: Landmarks on the Oregon Trail Full Citation: Earl R Harris, “Courthouse and Jail Rocks: Landmarks on the Oregon Trail,” Nebraska History 43 (1962): 29-51 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1962OregonTrail.pdf Date: 8/01/2016 Article Summary: Many routes to the West passed Courthouse Rock and Jail Rock. Harris lists and provides quotes from nineteenth-century pioneers’ journals commenting on the appearance of the two landmarks. Scroll down for complete article. Cataloging Information: Names: Samuel Parker, Alfred Jacob Miller Place Names: Scottsbluff [Scotts Bluff] and Bridgeport, Nebraska; Julesburg, Colorado Routes West: Oregon-California Trail, Mormon Trail, Black Hills gold rush trail Keywords: Courthouse Rock, Jail Rock, Sidney to Deadwood stagecoach line, Pony Express, Hackaday & Liggett mail coach, -

Mormon Trail Network in Nebraska, 1846-1868: a New Look

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 24 Issue 3 Article 6 7-1-1984 Mormon Trail Network in Nebraska, 1846-1868: A New Look Stanley B. Kimball Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Kimball, Stanley B. (1984) "Mormon Trail Network in Nebraska, 1846-1868: A New Look," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 24 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol24/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Kimball: Mormon Trail Network in Nebraska, 1846-1868: A New Look mormon trail network in nebraska 1846 1868 A new look stanley B kimball for more than twenty years during the mid nineteenth century between 1846 and 1868 thousands of cormonsmormons traversed southern nebraska going east and west utilizing a network of trails aggregating well over 1800 miles considerably more than the famous 1300 mile long mormon trail from nauvoo illinois to the valley of the great salt lake 1 to date interest in and knowledge of these nebraska trails has focused largely on the pioneer route of 1847 but there were many other trails and variants A new picture of mormon migration in nebraska is emerging showing that state to have been much more widely traveled by cormonsmormons than has heretofore been recognized we are just now beginning to