Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dying Languages: Last of the Siletz Speakers 1/14/08 12:09 PM

Newhouse News Service - Dying Languages: Last Of The Siletz Speakers 1/14/08 12:09 PM Monday January 14, 2008 Search the Newhouse site ABOUT NEWHOUSE | TOP STORIES | AROUND THE NATION | SPECIAL REPORTS | CORRESPONDENTS | PHOTOS Newhouse Newspapers Dying Languages: Last Of The Siletz Speakers Newhouse Spotlight The Ann Arbor News By NIKOLE HANNAH-JONES The Bay City Times c.2007 Newhouse News Service The Birmingham News SILETZ, Ore. — "Chabayu.'' Bud The Bridgeton News Lane presses his lips against the The Oregonian of Portland, Ore., is The Express-Times tiny ear of his blue-eyed the Pacific Northwest's largest daily grandbaby and whispers her newspaper. Its coverage emphasis is The Flint Journal Native name. local and regional, with significant The Gloucester County Times reporting teams dedicated to education, the environment, crime, The Grand Rapids Press "Ghaa-yalh,'' he beckons — business, sports and regional issues. "come here'' — in words so old, The Huntsville Times ears heard them millennia before The Jackson Citizen Patriot anyone with blue eyes walked Featured Correspondent this land. The Jersey Journal He hopes to teach her, with his Sam Ali, The Star-Ledger The Kalamazoo Gazette voice, this tongue that almost no one else understands. Bud Lane, the only instructor of Coast Athabaskan, hopes The Mississippi Press to teach the language to his 1-year-old granddaughter, Sam Ali, an award- Halli Chabayu Skauge. (Photo by Fredrick D. Joe) winning business The Muskegon Chronicle As the Confederated Tribes of writer, has spent The Oregonian Siletz Indians celebrate 30 years the past nine years since they won back tribal status from the federal government, the language of their at The Star-Ledger The Patriot-News people is dying. -

LESS NEWS IS BAD NEWS the Media Crisis and New Jersey’S News Deficit

Advancing progressive policy change since 1997 October 2009 LESS NEWS IS BAD NEWS The Media Crisis and New Jersey’s News Deficit A Report from New Jersey Policy Perspective and the Sandra Starr Foundation By Scott Weingart INTRODUCTION an electorate that receives little local news coverage and has relatively little knowledge of local and state politics . To make On July 23, 2009, the Federal Bureau of Investigation matters worse, the number of professional reporters in the state announced the arrests of 44 people, including half a dozen has fallen in recent years . New Jersey public officeholders, on charges ranging from po - litical corruption to trafficking in human organs. The massive New Jersey has faced a chronic news deficit because of peculi - corruption sweep ran on network and cable news and grabbed arities of its geography and economic development. From the headlines in the next day’s papers across the country. If New time of the nation’s founding, the state has developed in the Jerseyans were surprised, it was only by the scale of the opera - shadow of the two great cities across its borders, NewYork and tion. In an October, 2007 poll, nearly two-thirds of those asked Philadelphia, and failed to develop a major urban center of its had agreed that New Jersey has “a lot” of political corruption. 1 own. Today, New Jersey’s largest city, Newark, is home to just 3.2 percent of the state’s population, and rather than serving as New Jersey has a notorious and well-deserved reputation for an independent media center, Newark falls within the larger corrupt government. -

Workers! Unite All Forces Martin Balks Still Awaits Frankensteen Real Challenge Against the Union Wreckers! Plot Ln U.A.W

WORKERS OF THE FOR THE FOURTH Socialist Appeal INTERNATIONAL! WORLD UNITE! OFFICIAL WEEKLY ORGAN OF THE SOCIALIST WORKERS PARTY Vol. II. - No. 20. Saturday, May 14, 1938 Five Cents per Copy Hague’s Rule Workers! Unite All Forces Martin Balks Still Awaits Frankensteen Real Challenge Against the Union Wreckers! Plot ln U.A.W. By JA M E S P. C A N N O N where you will, from one end of the country to another, in one union after another, the record of internal discord Browder’s Candidate For Union Presidency Gets Farmer-Labor Congressmen, Acting On Advice Of The “ big push” of the Communist Party to take over describes the fever chart of sick unions in convulsive Stalinist I. L. D., Fail To Make Good On or smash the United Auto Workers raises a question struggles to throw off an alien poison. The name of Rebuff At Executive Board Meeting; Threat To Defy New Jersey Dictator which is rapidly coming to a head in many unions. this poison is Stalinism. Stalinists Begin to Squirm Supported by a strong press and apparatus, and with huge funds at their disposal, the Stalinists have become Crisis Aggravates Union Problems FREE SPEECH FIGHT IMPERATIVE a big factor in the trade union movement, especially The problems of the trade unions are many and UNION-BUSTERS STRIKE SNAG in the C.I.O. Catering to every prejudice of the most varied. These problems are aggravated under condi backward workers, combining with the worst types of Boss Hague, his private police force, and his army of tions of the deepening crisis. -

Vclt.Y-"Hospital, Nurses Homes ^-: X|Jersey^'City""Medical"Cetiter

;l/Jiirlfe^::VClt.y-"Hospital, Nurses Homes HABS No. NJ-891-A ■^-: x|Jersey^'City""Medical"Cetiter, Nurses Homes C:^-^fe-:;i::arid NoV 2) ";;SlI2-114- Clinton/Place - ;F jersey" City ;:-:/'.. :;/Hti4son Gpuiity -::/;&e# -Jersey r PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Mid-Atlantic Region, National Park Service Department of the Interior Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY IH-fc- JERSEY CITY HOSPITAL, NURSES HOMES HABS No. NJ-891-A (Jersey City Medical Center, Nurses Homes No. 1 and No. 2) Location: 112-114 Clifton place, Jersey City, Hudson County, New Jersey Present Owner: City of Jersey City Present Use : Demolished March, 1982; site now holds a parking facility Significance: Established in 1907, the hospital Nurses School existed until about I960, Nurses Homes No. 1 and No. 2 (occasionally called Central Hall and West Hall, respectively), built in 1918 and 1917, not only housed the hospital's nurses but also the entire Nurses School in the 1920s. Architecturally, these buildings represent the early stages of the career of John T. Rowland, the most important architect in Jersey City during the first half of the twentieth century. PART I. HISTORICAL INFORMATION A. Physical History: 1. Dates of construction: Nurses Home No. 1 - 1918; Nurses Home No. 2 - 1917 2. Architect: John T. Rowland, Jr. While no comprehensive study has been made of Rowland or his architecture, it can be stated that he was the most important architect in Jersey City, if not Hudson County, during the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Rockland County, New York, on October 20, 1872. -

Dr. Henry C. Black Dies Shepard Receives Great Freshmen Defeated in St

l'he Undergraduate Publication of ~tinitp t ' C!tolltge Volume XXIII HARTFORD, CONN., FRIDAY, M.A!R:CH 25, 1927 Number 22 DR. HENRY C. BLACK DIES SHEPARD RECEIVES GREAT FRESHMEN DEFEATED IN ST. OGILBY DISCUSSES STUDENT JUNIOR 'VARSITY HONOR. PATRICK'S DAY SCRAP. SUICIDES. BASKETBALl.. Was Recently Elected Trustee and Lays Part Blame on Church Awarded Guggenheim Fellowship S<•phomores Show Efficient Organiza Leeke's Men Make Creditable Long a Prominent Alumnus. Formalism. for 1927-28. tion. Showing. Dr. Henry Campbell Black, 67 years Formalisms of the church that run Professor Odell Shepard, Goodwin · About the seventh hour on th(> The Junior 'Varsity basketball years old, law ·author and editor of the cNmter to the experience of college .Professor of English Literature and morning of March 17, in the year o: proved to be one of the bright lights "Constitutional Review," died Satur cur Lord 1927, it befell that the mem f. tudents are partly responsible for of the basketball season. While the day afternoon at 2.45 o'clock at his head of the English department, has been awarded a Guggenheim Fellow bers of the Class of '29, duly enrolled many student suicides, in the opinion 'varsity was unable to score many 1·esidence, 2516 Fourteenth Street, of President Remsen B. Ogilby. ship for the year 1927-28. The fel 1n Trinity College, handed to the viotories to their credit the juniors Washington, D. C., after an illness of "Of grave concern to us," said Dr. lowship is one of those awarded by members of the Class of '30 what made the fine record of eleven wins three weeks. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

Minutes Are Available for Perusal and Approval

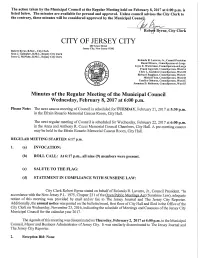

The action taken by the IVIunicipal Council at the Regular Meeting held on February 8, 2017 at 6:00 p.m. is listed below. The minutes are available for perusal and approval. Unless council advises the City Clerk to the contrary, these minutes will be considered approved by the Municipal Council. Robt^fc Byrne, City Clerk CITY OF JERSEY CITY 2SO Grove Street Jersey City, New Jersey 07302 Robert Byrnc, R.M.C., City Clerk Scan J. Gallagher, R.M.C., Deputy City Cicrk Irene G. McNulty, R.M.C., Deputy City Clerk Rolando R. Lavarro, Jr., Council President Daniel Rivcra, Councilpcrson-at-Large Joyce E. Watterman, Councilperson-at-Large Frank Gajewski, Councilperson, Ward A Chris L. Gadsden Councilpcrson, Ward B Richard Boggiano, Councilpcrson, Ward C Michael Yun, Councilperson, Ward D Candice Osborne, Councilperson, Ward E Jermaine D. Robinson, Councilperson, Ward F Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Municipal Council Wednesday, February 8, 2017 at 6:00 p.m. Please Note: The next caucus meeting of Council is scheduled for TUESDAY, February 21, 2017 at 5:30 p.m. in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. The next regular meeting of Council is scheduled for Wednesday, February 22, 2017 at 6:00 p.m. in the Anna and Anthony R. Cucci Memorial Council Chambers, City Hall. A pre-meeting caucus may be held in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. REGULAR MEETING STARTED: 6:17 p.m. 1. (a) INVOCATION: (b) ROLL CALL: At 6:17 p.m,, all nine (9) members were present. (c) SALUTE TO THE FLAG: (d) STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SUNSHINE LAW: City Clerk Robert Byrne stated on behalf of Rolando R. -

On London^ 3:30 to -4 P

lU RTEEir AU nsambers of S t Mary's Bible class ars ro<iuested to meet Sun Manoheaier ut Town day morning at nine o'clock, to St. James’ (Uacuas matters pertaining “ Date Book work ft>r the coming year. ■m ncular mantIUy meeting / Tomorrow . P__m PolUh-Ainerican AthleUc For Over Fifty Years ^ Oct. 6,—Coon trials at Manches Ik will held Monday night at Bodi/Parties E^or^ Bride Gets Gifts ter ,Coon and Fox Club grounds off MANCHEST]BR, CONN.^ MONDAY, OCTOBER 7, 1940 (FOURTEEN PAGES) ck, at the CUnton atreet Route 44 in Coventry. ididate fo r /^ le e t - M yt DONALD PUCK VOL. LX., NO. 6 (OImhUM AdvsrtWnff M rag* U) I. AU membe^ are urged At Shower Party Arthur Keating Tells of Also, Amateur Night at S t and be on time ae there John's church. an in South/Windsor I'biialneei to be dlaeuased. First Time . That He kext Week^ - , / . Took Part in ,the Sem „ Mary’s T. P. F. will bowl to- Mrs. Harry Rudeen was the Oct. 7. — First fali'meetlng With town elections being held ENaosa m m s iu t e i, s t kt at'8 o’clock at the West Slde Chamlnade Musical Club at C< in nearly alj OL the towns and The four newly appointed guest of- honor last .night at a ites; Oldest Member. ter churcb, 2:80 p. m. cities in OonneiAlcut next Monday IrS SAFE m SM M iNonEi 1 who will be In charge are mlsceUaneous shower at the home diet. -

Franklin Roosevelt, Frank Hague, and the Presidential Election of 1936 in New Jersey

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Winter 2016 120 “A Common Interest” Franklin Roosevelt, Frank Hague, and the Presidential Election of 1936 in New Jersey By Si Sheppard DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v2i1.30 The Great Depression and the New Deal forged a mutually beneficial alliance between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Mayor Frank Hague of Jersey City. Each needed the other. Hague benefited from the federal funds he was allocated by the New Deal relief agencies. Channeling this government assistance through his political machine in Jersey City enabled him to consolidate his control over Hudson County and ultimately become the dominant figure of the Democratic Party in New Jersey. In return, Hague pledged to secure New Jersey for Roosevelt in his reelection campaign. Ironically, Hague got the better of this arrangement. Roosevelt’s personal popularity would have ensured his reelection in 1936 regardless of Hague’s level of commitment. But by entrenching Hague’s authority, as the New Deal tide ebbed over the ensuing years, and elections in New Jersey became more competitive, the President became ever more dependent on the capacity of the Mayor to deliver the votes he needed. This necessitated a policy of willful indifference towards Hague’s increasingly autocratic and corrupt maladministration. New Jersey today is a loyal “Blue” state, having delivered its electoral votes to the Democratic Party’s candidate for President in every election for a generation. That was not always the case, however; when Franklin D. Roosevelt ran for reelection in 1936, New Jersey was considered a key “swing” state. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

RED BANK SECTION and Surroundlnf Town* T»M Mrlmflv and Without Bias RED BANK REGISTER ONE

AIX the NEWS of RED BANK SECTION and Surroundlnf Town* T»M mrlMflv and Without Bias RED BANK REGISTER ONE VOLUME LX1II, NO. 8. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, AUGUST 15, 1940. PAGES 1 TO 14« Shrewsbury Hoie No Reduction In Did Sapp Sock Social Service To Spoure With Saucer?, Company Opposes Interest Rate On Mrs. Vinnle T. Sapp of M5 River Dollar Days In Red Bank street was taken to Riverview hos- Hold Annual Session Fire Ordinance Taxes At Rumson pital Monday morning with bruises on her forehead and cheek and a cut on the forehead which was Chief Says New „ Finance Committee closed with one stitch, received dur- Today, Tomorrow and Sat.; Six Student Nuriet to Receive ing an argument with her husband, Law Too Elaborate- Decides to Retain Thomas Sapp. Mrs. Sapp explained that she threw Certificates September 4 To Seek Changes Eight Per Cent Rate a saucer at her husband and In some mysterious way the saucer returned Store-Wide Bargains Galore The Monmouth. County Organiza- Members of Shrewsbury Hose com- The Interest rat* on delinquent to bruise her. Mrs. Sapp refused tion (or Social Service will hold 1U pany Tueaday night went on record taxes in Rumson will remain at to aay whether Sapp caught the annual meeting Wednesday, Septem- "Abe," Boat Porter aa unanimously opposed to the new eight per cent. Councilman Sheldon aaucer and returned it on the wing Legion Meets Warning Period For Many Merchants Co- ber 4, at Brookdale Farm, Llncroft, fire ordinance which waa introduced T. Coleman, chairman of the finance or whether the recalcitrant plate home of the president of the organ- and pawed on first reading Tueaday committee, reported to the mayor boom e ran Red to damage her face.