Dying Languages: Last of the Siletz Speakers 1/14/08 12:09 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

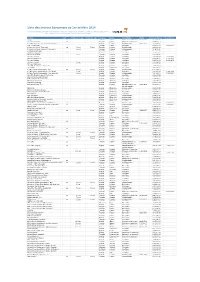

Liste Des Sources Europresse Au 1Er Octobre 2016

Liste des sources Europresse au 1er octobre 2016 Document confidentiel, liste sujette à changement, les embargos sont imposés par les éditeurs, le catalogue intégral est disponible en ligne : www.europresse.com puis "sources" et "nos sources en un clin d'œil" Source Pdf Embargo texte Embargo pdf Langue Pays Périodicité ISSN Début archives Fin archives 01 net oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 1276-519X 2005/01/10 01 net - Hors-série oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 2014/04/01 100 Mile House Free Press (South Cariboo) Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 0843-0403 2008/04/09 18h, Le (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/04 2014/02/18 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) oui 7 jours 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2013/04/09 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) (site web) 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2004/01/06 20 Minutes (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/30 24 Heures (Suisse) oui Français Suisse Quotidien 2005/07/07 24 heures Montréal 1 jour Français Canada Quotidien 2012/04/04 24 hours Calgary Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Edmonton Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Ottawa Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/02 2013/08/02 24 hours Toronto 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 hours Vancouver 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 x 7 News (Bahrain) (web site) Anglais Bahreïn Quotidien 2016/09/04 3BL Media Anglais États-Unis En continu 2013/08/23 40-Mile County Commentator, The oui 7 jours 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2001/09/04 40-Mile County Commentator, The (blogs) 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/05/08 2016/05/31 40-Mile County Commentator, The (web site) 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2011/03/02 2016/05/31 98.5 FM (Montréal, QC) (réf. -

Saginaw County Recreation Plan 2009 - 2013 52 Saginaw County Wants Community Input for Recreation Plan

. Appendix B Public Input Documentation DRAFT Saginaw County Recreation Plan 2009 - 2013 52 Saginaw County Wants Community Input for Recreation Plan FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: December 9, 2008 Saginaw County – The Saginaw County Parks and Recreation Commission wants to hear from the community about its parks and recreation facilities at a Community Input Open House held on Thursday, December 18 at the Saginaw County Governmental Center in Room LL006 from 4:30 p.m. until 6:30 p.m. Saginaw County residents are invited to stop by for a few moments to give their ideas on how the parks system can be improved. Saginaw County is in the process of updating its five year recreation plan. When completed, the plan will provide direction for the Parks and Recreation Commission and it will establish grant eligibility with the Michigan Department of National Resources. For more information about the plan or to offer input, visit http://SaginawCountyRecPlan.wordpress.com. END Contact: John Schmude, Director, Saginaw County Parks and Recreation Commission Phone: (989) 790-5280 Saginaw Home Page Page 1 of 1 ---- Department Listing ---- State Revenue Sharing 2009 Saginaw County Boater Safety Classes Parks Recreation Plan Saginaw County Recreation Plan - Online Survey Equalization LIVE Property Search Saginaw County Clean Indoor Air Regulation Clerk's Directory Home | Board of Commissioners | County Officials | Department Listing | Employee Services | Current Events | Event Center | Employment Opportunities | Related Links | Contact Information | Searches | Site Map Questions or suggestions? E-mail the webmaster here. Copyright © 2003 Saginaw County http://www.saginawcounty.com/Home.htm 1/14/2009 Page 1 of 3 http://www.saginawcounty.com/parks/ 1/14/2009 Mlive.com's Printer -Friendly Page Page 1 of 2 METRO BRIEFS Wednesday, December 17, 2008 Saginaw News Park plans forming Want a new trail to ride your bike on? Or a spinning merry go-round at a Saginaw County park? The County Parks and Recreation Department will ask for public opinion at an open house from 4:30 p.m to 6:30 p.m. -

Not for Immediate Release

Contact: Name Dan Gaydou Email [email protected] Phone 616-222-5818 DIGITAL NEWS AND INFORMATION COMPANY, MLIVE MEDIA GROUP ANNOUNCED TODAY New Company to Serve Communities Across Michigan with Innovative Digital and Print Media Products. Key Support Services to be provided by Advance Central Services Michigan. Grand Rapids, Michigan – Nov. 2, 2011 – Two new companies – MLive Media Group and Advance Central Services Michigan – will take over the operations of Booth Newspapers and MLive.com, it was announced today by Dan Gaydou, president of MLive Media Group. The Michigan-based entities, which will begin operating on February 2, 2012, will serve the changing news and information needs of communities across Michigan. MLive Media Group will be a digital-first media company that encompasses all content, sales and marketing operations for its digital and print properties in Michigan, including all current newspapers (The Grand Rapids Press, The Muskegon Chronicle, The Jackson Citizen Patriot, The Flint Journal, The Bay City Times, The Saginaw News, Kalamazoo Gazette, AnnArbor.com, Advance Weeklies) and the MLive.com and AnnArbor.com web sites. “The news and advertising landscape is changing fast, but we are well-positioned to use our talented team and our long record of journalistic excellence to create a dynamic, competitive, digitally oriented news operation,” Gaydou said. “We will be highly responsive to the changing needs of our audiences, and deliver effective options for our advertisers and business partners. We are excited about our future and confident this new company will allow us to provide superior news coverage to our readers – online, on their phone or tablet, and in print. -

LESS NEWS IS BAD NEWS the Media Crisis and New Jersey’S News Deficit

Advancing progressive policy change since 1997 October 2009 LESS NEWS IS BAD NEWS The Media Crisis and New Jersey’s News Deficit A Report from New Jersey Policy Perspective and the Sandra Starr Foundation By Scott Weingart INTRODUCTION an electorate that receives little local news coverage and has relatively little knowledge of local and state politics . To make On July 23, 2009, the Federal Bureau of Investigation matters worse, the number of professional reporters in the state announced the arrests of 44 people, including half a dozen has fallen in recent years . New Jersey public officeholders, on charges ranging from po - litical corruption to trafficking in human organs. The massive New Jersey has faced a chronic news deficit because of peculi - corruption sweep ran on network and cable news and grabbed arities of its geography and economic development. From the headlines in the next day’s papers across the country. If New time of the nation’s founding, the state has developed in the Jerseyans were surprised, it was only by the scale of the opera - shadow of the two great cities across its borders, NewYork and tion. In an October, 2007 poll, nearly two-thirds of those asked Philadelphia, and failed to develop a major urban center of its had agreed that New Jersey has “a lot” of political corruption. 1 own. Today, New Jersey’s largest city, Newark, is home to just 3.2 percent of the state’s population, and rather than serving as New Jersey has a notorious and well-deserved reputation for an independent media center, Newark falls within the larger corrupt government. -

Delivering Timely Environmental Information to Your Community

United States Office of Research and Development EPA/625/R-01/010 Environmental Protection Office of Environmental Information September 2001 Agency Washington, DC 20460 http://www.epa.gov/empact Delivering Timely Environmental Information to Your Community The Boulder Area Sustainability Information Network (BASIN) E M P A C T Environmental Monitoring for Public Access & Community Tracking Disclaimer This document has been reviewed by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and ap- proved for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute en- dorsement or recommendation of their use. EPA/625/R-01/010 September 2001 Delivering Timely Environmental Information to Your Community The Boulder Area Sustainability Information Network (BASIN) United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development National Risk Management Research Laboratory Cincinnati, OH 45268 Recycled/Recyclable Printed with vegetable- based ink on paper that contains a minimum of 50% post-consumer fiber content processed chlorine free CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Dan Petersen of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Risk Management Laboratory, served as principal author of this handbook and managed its development with support of Pacific Environmental Services, Inc., an EPA contractor. The following contributing authors represent the BASIN team and provided valuable assistance for the development of the handbook: BASIN Team Larry Barber, United States Geological Survey (USGS), Boulder, Colorado Michael -

Table 10 Papers Not Responding to the ASNE Survey Ranked by Circulation

Table 10 Papers not responding to the ASNE survey Ranked by circulation (DNR = did not report to ASNE last year, too.) Source: Report to the Knight Foundation, May 2004 by Bill Dedman and Stephen K. Doig. The full report is at http://www.asu.edu/cronkite/asne Rank Newspaper, State Weekday Ownership Circulation Staff non-white % circulation area non- for previous year white % (year-end 2002), if paper responded 1 New York Post, New York 652,426 40.3 DNR 2 Chicago Sun-Times, Illinois 481,798 Hollinger International 50.3 DNR (Ill.) 3 The Star-Ledger, Newark, New Jersey 408,672 Advance (Newhouse) 36.8 16.5 (N.Y.) 4 The Columbus Dispatch, Ohio 252,564 17.3 DNR 5 Boston Herald, Massachusetts 241,457 Herald Media (Mass.) 21.1 5.5 6 The Daily Oklahoman, Oklahoma City, 207,538 24.7 21.1 Oklahoma 7 Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Little Rock, 183,343 Wehco Media (Ark.) 22.1 DNR Arkansas 8 The Providence Journal, Rhode Island 167,609 Belo (Texas) 17.3 DNR Page 1 Rank Newspaper, State Weekday Ownership Circulation Staff non-white % circulation area non- for previous year white % (year-end 2002), if paper responded 9 Las Vegas Review-Journal, Nevada 160,391 Stephens Media Group 39.8 DNR (Donrey) (Nev.) 10 Daily Herald, Arlington Heights, 150,364 22.6 5.7 Illinois 11 The Washington Times, District of 102,255 64.3 DNR Columbia 12 The Post and Courier, Charleston, South 98,896 Evening Post Publishing 35.9 DNR Carolina (S.C.) 13 San Francisco Examiner, California 95,800 56.4 18.9 14 Mobile Register, Alabama 95,771 Advance (Newhouse) 33.0 8.6 (N.Y.) 15 The Advocate, -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

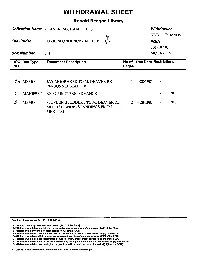

APRIL 1981 :Ii FOIA Fol-107/01 Box Number 7618 MCCARTIN 10 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages

WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name DEAVER, MICHAEL: FILES Withdrawer KDB 7/18/2005 File Folder CORRESPONDENCE-APRIL 1981 :ii FOIA FOl-107/01 Box Number 7618 MCCARTIN 10 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages i) MEMO JAY MOORHEAD TO M. DEAVER RE 1 4/28/1981 B6 PERSONNEL MATTER 2 MANIFEST RE SUMMIT PRE-ADVANCE 1 B6 B7(C) I®\ MEMO STEPHEN STUDDERT TOM. DEAVER RE 2 4/28/1981 B2 B7(E) MUTUAL UNDERSTANDINGS FROM MEETING Freedom of Information Act· [5 U.S.C. 552(b)) B·1 National security classified Information [(b)(1) of the FOIA] B-2 Release would disclose Internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA] B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA] B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial Information [(b)(4) of the FOIA] B-6 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA] B-7 Release would disclose information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA] B-8 Release would disclose Information concerning the regulation of financial Institutions [(b)(B) of the FOIA] B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA] C. Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in donor's deed of gift. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON April 28, 1981 l - ;". Dear Mr. Epple: Thank you for your kind letter and ex pression of continued support of President Reagan and his staff. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

Chette Williams « East Alabama Living

10/1/2014 Chette Williams « East Alabama Living 1. Username Username 2. Password •••••••• 3. Remember Me Remember Me 4. Log In 1. Username Username 2. E-mail E‑mail 3. A password will be e-mailed to you. 4. Register home about advertise contact us Subscribe locations articles current issue sections weddings recipes & tablescapes getaways & day trips features login register Register for free to take full advantage of this site. If you're already registered, please login. search Today is Wednesday October 1, 2014 Chette Williams http://www.eastalabamaliving.com/features/chette-williams/ 1/7 10/1/2014 Chette Williams « East Alabama Living By Ann Cipperly Snapshots of family, framed photos of Auburn Tigers praying after games, a National Championship football, signed helmet from days of playing football with Bo Jackson, and other items on shelves reveal the life story of Chaplain Chette Williams at the Auburn University Athletic Department. On a round table are copies of Williams’s two books, “Hard-Fighting Soldier” and “The Broken Road,” published this past summer. One of the most important photos leaning against the books on the shelves is a photo of a small white church, Old Mountain Top Baptist Church in Winston, Ga. Williams looks at this photo every day to remind himself of his humble beginning and where God got his attention. It is the church he attended with his mother and six brothers, where he was baptized in the creek in back, where he buried a brother and spoke at his father’s funeral. Williams grew up not far from the church. -

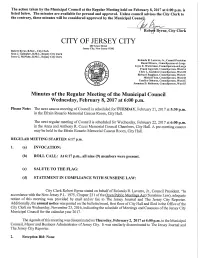

Minutes Are Available for Perusal and Approval

The action taken by the IVIunicipal Council at the Regular Meeting held on February 8, 2017 at 6:00 p.m. is listed below. The minutes are available for perusal and approval. Unless council advises the City Clerk to the contrary, these minutes will be considered approved by the Municipal Council. Robt^fc Byrne, City Clerk CITY OF JERSEY CITY 2SO Grove Street Jersey City, New Jersey 07302 Robert Byrnc, R.M.C., City Clerk Scan J. Gallagher, R.M.C., Deputy City Cicrk Irene G. McNulty, R.M.C., Deputy City Clerk Rolando R. Lavarro, Jr., Council President Daniel Rivcra, Councilpcrson-at-Large Joyce E. Watterman, Councilperson-at-Large Frank Gajewski, Councilperson, Ward A Chris L. Gadsden Councilpcrson, Ward B Richard Boggiano, Councilpcrson, Ward C Michael Yun, Councilperson, Ward D Candice Osborne, Councilperson, Ward E Jermaine D. Robinson, Councilperson, Ward F Minutes of the Regular Meeting of the Municipal Council Wednesday, February 8, 2017 at 6:00 p.m. Please Note: The next caucus meeting of Council is scheduled for TUESDAY, February 21, 2017 at 5:30 p.m. in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. The next regular meeting of Council is scheduled for Wednesday, February 22, 2017 at 6:00 p.m. in the Anna and Anthony R. Cucci Memorial Council Chambers, City Hall. A pre-meeting caucus may be held in the Efrain Rosario Memorial Caucus Room, City Hall. REGULAR MEETING STARTED: 6:17 p.m. 1. (a) INVOCATION: (b) ROLL CALL: At 6:17 p.m,, all nine (9) members were present. (c) SALUTE TO THE FLAG: (d) STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SUNSHINE LAW: City Clerk Robert Byrne stated on behalf of Rolando R. -

Table 2: Top 200 Newspapers in Circulation, Ranked by Newsroom

Table 2 Top 200 newspapers ranked by Newsroom Diversity Index (The Diversity Index is the newsroom minority percentage divided by the community minority percentage. DNR = did not report to ASNE.) Rank Newspaper, State Diversity Staff Community Source Ownership Circulation in index minority minority top 200 1 Argus Leader, Sioux Falls, South Dakota 199 12.5% 6.3% ZIP Gannett 54,147 2 Press & Sun-Bulletin, Binghamton, New York 195 13.2% 6.8% ZIP Gannett 57,576 3 Bucks County Courier Times, Levittown, Pennsylvania 183 20.0% 11.0% ZIP Calkins 67,094 4 Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, Maine 163 6.4% 3.9% ZIP Seattle Times 76,833 5 Lincoln Journal Star, Nebraska 159 12.9% 8.1% ZIP Lee 74,586 6 Lexington Herald-Leader, Kentucky 156 12.4% 7.9% COUNTIES Knight-Ridder 108,892 7 The Beacon Journal, Akron, Ohio 150 17.7% 11.8% ZIP Knight-Ridder 134,774 8 Springfield News-Leader, Missouri 148 8.8% 5.9% ZIP Gannett 62,158 9 Asheville Citizen-Times, North Carolina 138 13.3% 9.7% ZIP Gannett 55,847 10 The Des Moines Register, Iowa 124 9.0% 7.3% ZIP Gannett 152,633 11 Green Bay Press-Gazette, Wisconsin 121 10.7% 8.8% ZIP Gannett 56,943 12 The Scranton Times and The Tribune, Pennsylvania 119 4.6% 3.9% ZIP Times-Shamrock 63,230 13 The Syracuse Newspapers, New York 115 13.1% 11.3% ZIP Advance (Newhouse) 123,836 14 Florida Today, Melbourne, Florida 115 18.9% 16.5% ZIP Gannett 86,116 15 Kalamazoo Gazette, Michigan 114 15.1% 13.2% ZIP Advance (Newhouse) 55,761 16 The Tennessean, Nashville, Tennessee 114 19.9% 17.5% ZIP Gannett 184,106 17 The Boston