Tipping the Scales: Equity and Diversity at the Bar1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Women's Voices in Ancient and Modern Times”

“Women’s Voices in Ancient and Modern Times” Speech delivered at the ANU Law Students’ Society Women in Law Breakfast 22 March 2021 I acknowledge the traditional custodians of this land and pay my respects to their elders— past, present, and emerging. I acknowledge that sovereignty over this land was never ceded. I extend my respects to all First Nations people who may be present today. I acknowledge that, in Australia over the last 30 years, at least 442 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have died in custody. It is a pleasure to be speaking to a room of young women who will be part of the next generation of Australian and international lawyers. I hope that we will also see you in politics. In my youth, a very long time ago, the aspirational statement was “a woman’s place is in the House—and in the Senate”. As recent events show, that sentiment remains aspirational today. Women’s voices are still being devalued. Today, I will speak about the voices of women in ancient and modern democracies. Women in Ancient Greece Since ancient times, women’s voices have been silenced. While we could all name outstanding male Ancient Greek philosophers, poets, politicians, and physicians, how many of us know of eminent women from that time? The few women’s voices of which we do know are those of mythical figures. In Ancient Greece, the gods and goddesses walked among the populace, and people were ever mindful of their presence. They exerted a powerful influence. Who were the goddesses? Athena was a warrior, a judge, and a giver of wisdom, but she was born full-grown from her father (she had no mother) and she remained virginal. -

Notes for Lawyers Weekly

Lawyers Weekly – Women in Law Awards Melbourne THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE RUTH McCOLL AO COURT OF APPEAL SUPREME COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY, 17 OCTOBER 2014 1 I am honoured to accept the Lasting Legacy Award this evening. 2 I am particularly honoured, in receiving the Award, to follow in the footsteps of Professor Gillian Triggs, the distinguished President of the Australian Human Rights Commission and former Dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Sydney and Sharon Cook, the Managing Partner of Henry Davis York. Both have left large footprints in contributing to gender equality in the profession, footsteps I feel I can only tiptoe in. 3 I also thank Lawyers Weekly on its initiative in conducting this Awards Ceremony which, I am sure, plays a valuable role in communicating to the legal community and perhaps further afield, the success of so many terrific recipients across the board in legal practice. 4 I accept this Award, however, not only on my own behalf, but also, I hope, on behalf of the many women both who have preceded me in campaigning for gender equality in the legal profession and those who continue that campaign. Many of the latter are present tonight of course, including our keynote speaker, Fiona McLeod SC, a noted campaigner for gender equality and a distinguished past President of Australian Women Lawyers and another distinguished past President, Dominique Hogan-Doran. 5 Looking around this room this evening at this group of clearly highly successful women legal practitioners, it would be easy perhaps to lose sight of how far women have come in the legal profession. -

SULS Education Guide 2020

EDUCATION GUIDE 2020 Studying at Law School Advice on how to stay on top of your academics during your law degree. Degree Planning A comprehensive overview of the different law degree progressions to help you plan ahead. Study and Professional Experiences Discover the opportunities offered at USYD Law from exchange to international volunteering. Acknowledgments We acknowledge the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land that the University of Sydney is built upon, the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation. We acknowledge that this was and always will be Aboriginal Land and are proud to be on the lands of one of the oldest surviving cultures in existence. We respect the knowledge that traditional elders and Aboriginal people hold and pass on from generation to generation, and acknowledge the continuous fight for constitutional reform and treaty recognition to this day. We regret that white supremacy has been used to justify Indigenous dispossession, colonial rule and violence in the past, in particular, a legal and political system that still to this date doesn’t provide Aboriginal people with justice. Many thanks to everyone who made the production and publication of the 2020 Sydney University Law Society Education Guide possible. In particular, we would like to thank Rita Shackel (Associate Dean of Education), the Sydney Law School and the University of Sydney Union for their continued support of SULS and its publications. Editors Vice-President (Education): Natalie Leung Editor-in-Chief: Vaidehi Mahapatra Editorial Team: Zachary O’Meara, -

2378.Law Society Of

2378 NSW LAW SOCIETY@125: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE The Law Society of New South Wales 125th Anniversary Dinner Sydney Hilton, 30 July 2009. The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG THE LAW SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 125TH ANNIVERSARY DINNER SYDNEY HILTON, 30 JULY 2009. NSW LAW SOCIETY@125: PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG THE PAST Depending on the starting point one selects, this is a celebration of 125 years of the organised attorneys of New South Wales. Long before that time, the attorneys of the colony were banded together in a common cause. In 1824, they joined together to attempt to stave off the attempt by Robert Wardell and William Wentworth to exclude them from advocacy in the colony and to “confine them to their own profession1”. They also banded together in 1842 to confront Governor Gipps and to create the Sydney Law Library Society under the leadership of James Norton2. However, it was the formation of the Incorporated Law Institute of New South Wales in May 18843 that is usually taken as the starting point of the institutional life of the community of lawyers in this part of Australia. It is to commemorate that event that we come together to celebrate on this occasion. Former Justice of the High Court of Australia and President of the NSW Court of Appeal; President, Institute of Arbitrators & Mediators Australia. Solicitor of the Supreme Court of NSW (1962-67). 1 Entry on “Robert Wardell” in Australian Dictionary of Biography (MUP, 1967), Vol.2, 570 at 571. 2 “A History of Service to the Law” in Law Society Journal (NSW), July 2009, 50. -

Leading from the Bench: Women Jurists As Role Models

Leading from the Bench: Women Jurists as Role Models Remarks by the Honourable Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice of Victoria on the occasion of American Chamber of Commerce in Australia ‘Women in Leadership’ Breakfast at Crown, Melbourne 12 February 2015 Précis Women currently account for about one third of the Australian judiciary; an extraordinary achievement in a relatively short time. This figure is echoed in the United States. The Hon. Chief Justice Marilyn Warren AC, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria, celebrates the women who paved the way for judicial equality and who continue to act as role models and inspire others to continue the journey. Introduction Women are a relatively recent addition to the practice of law in Australia. It was just over a century ago in 1902 that Australia saw its first female law graduate, Ada Evans.1 Legend has it that her enrolment at the Sydney Law School was aided by a small stroke of good fortune or, rather, good timing. The Dean of Law at the time would never have accepted a woman, 1 Mary Gaudron, ‘Australian Women Lawyers’ (Speech to delivered at the launch of Australian Women Lawyers, High Court of Australia, 19 September 1997). Supreme Court of Victoria 12 February 2015 however luckily for Evans he was on leave at the time and her enrolment was accepted in his absence.2 Upon his return the Dean told Evans that ‘she did not have the physique for law’.3 However it was too late; Evans was not deterred. History had been made and the trailblazing had begun. -

The Case of Edith Haynes*

CHALLENGING THE LEGAL PROFESSION A CENTURY ON: THE CASE OF EDITH HAYNES* † MARGARET THORNTON This article focuses on Edith Haynes’ unsuccessful attempt to enter the legal profession in Western Australia. Although admitted to articles as a law student in 1900, she was denied permission to sit her intermediate examination by the Supreme Court of WA (In re Edith Haynes (1904) 6 WAR 209). Edith Haynes is of particular interest for two reasons. First, the decision denying her permission to sit the exam was an example of a ‘persons’ case’, which was typical of an array of cases in the English common law world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in which courts determined that women were not persons for the purpose of entering the professions or holding public office. Secondly, as all (white) women had been enfranchised in Australia at the time, the decision of the Supreme Court begs the question as to the meaning of active citizenship. The article concludes by hypothesising a different outcome for Edith Haynes by imagining an appeal to the newly established High Court of Australia. Contents I Introduction ................................................................................................1 II Edith Haynes 1876-1963...............................................................................4 III In Re Haynes ..................................................................................................6 IV The Citizenship Conundrum ...........................................................................9 V Imagining -

The First Women to Clear the Bar in New South Wales by Jenny Chambers

| LEGAL HISTORY | The first women to clear the bar in New South Wales By Jenny Chambers Early pioneers Women to practise at the NSW Bar by 1975 In 1824, Saxe Bannister (1790–1877) became the first Year of admission person to be admitted to practise as a barrister in New 1 Sybil Morrison 1924 South Wales. His admission was concurrent with his 2 Nerida Cohen 1935 being sworn into the office of attorney general of New 3 Ann Bernard 1941 South Wales with a right of private practice at the first 4 Beatrice Bateman 1942 sitting of the Supreme Court on 17 May 1824.1 5 Klara Rudlow 1953 Almost a century would pass before a woman was 6 Elizabeth Evatt 1955 admitted to the New South Wales Bar. That woman 7 Kathleen Trevelyan 1957 was Ada Evans (1872–1947), whose admission took 8 Janet Coombs 1959 place on 12 May 1921. Ada had graduated from 9 Helen Knox 1960 the University of Sydney’s Law School in 1902 (and, 10 Susanne Schreiner 1962 incidentally, was Australia’s first female law graduate). However, before Ada Evans could be admitted to 11 Mary Cass 1963 practise, the NSW legislature had to clarify the position 12 Cecily Backhouse 1964 as to whether a woman came within the meaning 13 Anna Frenkel 1964 of a ‘person’ and, concomitantly, could therefore be 14 Helen Gerondis 1965 determined to be a ‘properly qualified person’ and a 15 Margaret O’Toole 1965 ‘fit and proper person’ as those terms were understood 16 Beatrice Gray 1968 under the Legal Practitioners Act 1898 (NSW).2 The 17 Jenny Blackman 1968 question was resolved by the enactment of the Women’s 18 Mary Gaudron 1968 Legal Status Act 1918 (NSW). -

1 100 YEARS of WOMEN in LAW in NSW the Hon Justice M J Beazley

The Hon Justice M J Beazley AO 100 Years of Women in Law Carroll & O’Dea Lawyers Sydney, Australia 18 October 2018 100 YEARS OF WOMEN IN LAW IN NSW The Hon Justice M J Beazley AO* President, New South Wales Court of Appeal 1 [SLIDE 1] In 1873, the United States Supreme Court upheld a decision refusing Myra Bradwell’s admission to the Illinois Bar. In rejecting her application, the Court declared that it was an “almost axiomatic truth” that “God designed the sexes to occupy different spheres of action, and that it belonged to men to make, apply, and execute the laws.”1 On appeal, Justice Bradley agreed with this sentiment and remarked that: “the natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life”. 2 2 It is this school of thought – that women, by reason of their sex, are unsuited to the intellectual rigour of the law – that has been debunked, albeit grindingly slowly, over the last 100 years. 3 Today, I want to step you through the key milestones for women in the legal profession over the last century, and to reflect briefly on the ongoing issues and challenges. But first, let us acknowledge the incredible contributions that women have made to the development of the legal profession to date. Indigenous Women as Lawmakers 4 In NSW, we point to 1918 as the defining moment when women were granted the right to practice law. However, women in Australia were practising law well before 1918. -

One of the 'Laws Women Need'1

| LEGAL HISTORY | One of the ‘Laws Women Need’1 Tony Cunneen discusses the passage of the The Women’s Legal Status Act of 1918. Introduction The Women’s Legal Status Act of 1918 was one of the most significant pieces of legislation affecting the New South Wales legal profession in the twentieth century. This Act gave women the legal right to become lawyers. In addition it gave women the right to be elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly. There was protracted lobbying for these rights by a number of women. The bill was eventually presented to parliament by the state attorney general and Sydney barrister, David Robert Hall. The main reason for that exclusively male enclave finally passing the Act after so much delay was that both houses believed that women had proved themselves both worthy and deserving of the right to become lawyers and parliamentarians by their energetic public activities during the First World War. The Act was one of the positive outcomes of an otherwise tragic conflict. Hockey sticks and abuse at Sydney University Ada Evans. Photo: Sydney University Archives The federation of Australia had not completely solved of the pioneer’5, but she was reportedly so embittered the problem of the limited legal status of women. and alienated by the experience of battling to be Speaking in Maitland on 17 January 1901 Australia’s first admitted to practice after she graduated in 1902 that prime minister, Edmund Barton expressed his approval she did not act as a barrister even when she finally of universal suffrage but drew the line at admitting had the right to do so.6 Sydney University was not in ‘that the granting of suffrage should entitle women to general a comfortable place for women who wanted to occupy seats in parliament if elected’.2 His comment espouse feminist causes before the First World War – in indicates the kind of grudging recognition of women’s fact it could be decidedly intimidating whether or not rights, which persisted in the federation period. -

The Honourable Justice M J Beazley AO*

99 Judicial Officers’ Bulletin Published by the Judicial Commission of NSW December 2018, Volume 30 No 11 100 years of women in the law The Honourable Justice M J Beazley AO* To acknowledge the centenary of the Women’s Legal Status Act 1918, which allowed women to practise law in NSW, the President of the Court of Appeal reflects on the slow acceptance of women into the legal profession and some of the trailblazing women who “did it first”. On 5 December 1918, the NSW legislature passed the stipendiary or police magistrate, or a justice of the peace; or Women’s Legal Status Act 1918 (NSW) (the Act). The Act was admitted and to practise as a barrister or solicitor of the NSW the culmination of protracted lobbying by women activists of Supreme Court, or to practise as a conveyancer. the time, including the English suffragette Adela Pankhurst, who visited Sydney in 1914, sisters Belle and Annie Goldring, Sixty-two years later, in 1980, Jane Mathews became the Rose Scott and Kate Dwyer. A Bill was originally introduced first woman to be appointed to the NSW District Court. into the NSW Legislative Assembly in August 1916, but She was only the second woman to have been appointed a withdrawn as it was ruled out of order. A second Bill lapsed. judge in Australia. Dame Roma Mitchell was the first, having The Women’s Legal Status Bill was eventually introduced been appointed to the South Australian Supreme Court in on 3 October 1918 by the NSW Attorney General and 1965. It is perhaps unsurprising that South Australia was the barrister, David Hall. -

Determination 2004 (No 1)

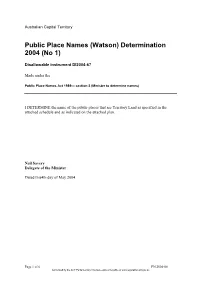

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Watson) Determination 2004 (No 1) Disallowable instrument DI2004-67 Made under the Public Place Names Act 1989— section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the name of the public places that are Territory Land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the attached plan. Neil Savery Delegate of the Minister Dated this4th day of May 2004. Page 1 of 6 PN 2004-08 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Watson) Determination2004 (No 1) Division of Watson: Judges and the legal profession NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Ada Evans Ada Emily Australian Barrister Street Evans Ada Evans was born in Wanstead, Essex in England and (1872-1947) migrated to Sydney, New South Wales in 1883. Ada graduated as a Bachelor of Arts from Sydney University in 1895 and a Bachelor of Laws in 1902 from the same University. The Dean of the Faculty of Law in the late 1880's was away on Sabbatical leave when Ada enrolled at the Law school. On his return, he was reported to have said that her stature was not appropriate for the profession of law but more appropriate for the profession of medicine. Nevertheless, she completed her course in 1902. It was not possible for her to be admitted to the Bar at that stage, as there was no precedent either in England or Australia for a woman to be admitted to the Bar. To be admitted, she had to be a "person" and this definition did not include women. -

To View a Century Downtown: Sydney University Law School's First

CENTURY DOWN TOWN Sydney University Law School’s First Hundred Years Edited by John and Judy Mackinolty Sydney University Law School ® 1991 by the Sydney University Law School This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism, review, or as otherwise permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Typeset, printed & bound by Southwood Press Pty Limited 80-92 Chapel Street, Marrickville, NSW For the publisher Sydney University Law School Phillip Street, Sydney ISBN 0 909777 22 5 Preface 1990 marks the Centenary of the Law School. Technically the Centenary of the Faculty of Law occurred in 1957, 100 years after the Faculty was formally established by the new University. In that sense, Sydney joins Melbourne as the two oldest law faculties in Australia. But, even less than the law itself, a law school is not just words on paper; it is people relating to each other, students and their teachers. Effectively the Faculty began its teaching existence in 1890. In that year the first full time Professor, Pitt Cobbett was appointed. Thus, and appropriately, the Law School celebrated its centenary in 1990, 33 years after the Faculty might have done. In addition to a formal structure, a law school needs a substantial one, stone, bricks and mortar in better architectural days, but if pressed to it, pre-stressed concrete. In its first century, as these chapters recount, the School was rather peripatetic — as if on circuit around Phillip Street.