Context, Craft, and Kerygma: Two Thousand Years of Great Sermons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Harmony of the Life of Paul

A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul A Chronological Study Harmonizing The Book Of Acts With Paul’s Epistles This material is from ExecutableOutlines.com, a web site containing sermon outlines and Bible studies by Mark A. Copeland. Visit the web site to browse or download additional material for church or personal use. The outlines were developed in the course of my ministry as a preacher of the gospel. Feel free to use them as they are, or adapt them to suit your own personal style. To God Be The Glory! Executable Outlines, Copyright © Mark A. Copeland, 2007 Mark A. Copeland A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul Table Of Contents Paul's Life Prior To Conversion 3 The Conversion Of Paul (36 A.D.) 6 Paul’s Early Years Of Service (36-45 A.D.) 10 First Missionary Journey, And Residence In Antioch (45-49 A.D.) 13 Conference In Jerusalem, And Return To Antioch (50 A.D.) 17 Second Missionary Journey (51-54 A.D.) 20 Third Missionary Journey (54-58 A.D.) 25 Arrest In Jerusalem (58 A.D.) 30 Imprisonment In Caesarea (58-60 A.D.) 33 The Voyage To Rome (60-61 A.D.) 37 First Roman Captivity (61-63 A.D.) 41 Between The First And Second Roman Captivity (63-67 A.D.) 45 The Second Roman Captivity (68 A.D.) 48 A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul 2 Mark A. Copeland A Harmony Of The Life Of Paul Paul's Life Prior To Conversion INTRODUCTION 1. One cannot deny the powerful impact the apostle Paul had on the growth and development of the early church.. -

How Was the Sermon? Mystery Is That the Spirit Blows Where It Wills and with Peculiar Results

C ALVIN THEOLOGI C AL S FORUMEMINARY The Sermon 1. BIBLICAL • The sermon content was derived from Scripture: 1 2 3 4 5 • The sermon helped you understand the text better: 1 2 3 4 5 • The sermon revealed how God is at work in the text: 1 2 3 4 5 How Was the• The sermonSermon? displayed the grace of God in Scripture: 1 2 3 4 5 1=Excellent 2=Very Good 3=Good 4=Average 5=Poor W INTER 2008 C ALVIN THEOLOGI C AL SEMINARY from the president FORUM Cornelius Plantinga, Jr. Providing Theological Leadership for the Church Volume 15, Number 1 Winter 2008 Dear Brothers and Sisters, REFLECTIONS ON Every Sunday they do it again: thousands of ministers stand before listeners PREACHING AND EVALUATION and preach a sermon to them. If the sermon works—if it “takes”—a primary cause will be the secret ministry of the Holy Spirit, moving mysteriously through 3 a congregation and inspiring Scripture all over again as it’s preached. Part of the How Was the Sermon? mystery is that the Spirit blows where it wills and with peculiar results. As every by Scott Hoezee preacher knows, a nicely crafted sermon sometimes falls flat. People listen to it 6 with mild interest, and then they go home. On other Sundays a preacher will Good Preaching Takes Good Elders! walk to the pulpit with a sermon that has been only roughly framed up in his by Howard Vanderwell (or her) mind. The preacher has been busy all week with weddings, funerals, and youth retreats, and on Sunday morning he isn’t ready to preach. -

CH 527 COURSE SYLLABUS the MEDIEVAL CHURCH and the REFORMATION from the Rise of Charlemagne to the Council of Trent Fall, 2020

CH 527 COURSE SYLLABUS THE MEDIEVAL CHURCH and THE REFORMATION From the Rise of Charlemagne to The Council of Trent Fall, 2020. Instructor: Fr. Luke Dysinger, OSB. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 805 482-2755: office ext 1045; room ext. 1068. Office Hours (St. Katharine 318) by arrangement, COURSE WEBSITE: through Sonis, or http://ldysinger.stjohnsem.edu DESCRIPTION: This course will introduce the history, theology, and spirituality of the Christian Church from the rise of Charlemagne (c. 800) to the Council of Trent (1563). This course will provide an overview of both the theological and spiritual traditions of the Medieval Church through the time of the Catholic Reformation, culminating in the Council of Trent. The rich ethnic and cultural diversity of Christian thought during this period will be highlighted through study of primary sources from the Jewish, Roman, Greek, Celtic, Anglo- European, Slavic, Middle-Eastern (Syriac), and Egyptian (Coptic) traditions. In order to profit from the cultural and ethnic diversity of the student body, students are encouraged to bring to classroom discussion the early and medieval origins of their cultural traditions: including, for example, the theological, liturgical, and spiritual emphases that distinguish Western Catholicism from Eastern traditions such as the Maronite, Chaldean, Melchite, Malabar, and Ruthenian churches. During each class selected primary and secondary texts will be studied and discussed. A large proportion of the primary texts will be taken from the Office of Readings. In this way students’ ongoing prayerful study of these texts in the liturgy will provide a deepening re-acquaintance with patristic and early medieval sources of Christian spirituality and doctrine. -

The Healing Ministry of Jesus As Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 6-2006 The eH aling Ministry of Jesus as Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels Alvin Lloyd Maragh Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Medical Humanities Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Maragh, Alvin Lloyd, "The eH aling Ministry of Jesus as Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels" (2006). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 457. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/457 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LOMA LINDA, CALIFORNIA LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY Faculty of Religion in conjunction with the Faculty of Graduate Studies The Healing Ministry of Jesus as Recorded in the Synoptic Gospels by Alvin Lloyd Maragh A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Clinical Ministry June 2006 CO 2006 Alvin Lloyd Maragh All Rights Reserved Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in his opinion is adequate in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree Master of Arts. Chairperson Siroj Sorajjakool, Ph.D7,-PrOfessor of Religion Johnny Ramirez-Johnson, Ed.D., Professor of Religion David Taylor, D.Min., Profetr of Religion 111 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank God for giving me the strength to complete this thesis. -

University Microfilms International T U T T L E , V Ir G in Ia G R a C E

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Doctrinal Controversies of the Carolingian Renaissance: Gottschalk of Orbais’ Teachings on Predestination*

ROCZNIKI FILOZOFICZNE Tom LXV, numer 3 – 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18290/rf.2017.65.3-3 ANDRZEJ P. STEFAŃCZYK * DOCTRINAL CONTROVERSIES OF THE CAROLINGIAN RENAISSANCE: GOTTSCHALK OF ORBAIS’ TEACHINGS ON PREDESTINATION* This paper is intended to outline the main areas of controversy in the dispute over predestination in the 9th century, which shook up or electrified the whole world of contemporary Western Christianity and was the most se- rious doctrinal crisis since Christian antiquity. In the first part I will sketch out the consequences of the writings of St. Augustine and the revival of sci- entific life and theological and philosophical reflection, which resulted in the emergence of new solutions and aporias in Christian doctrine—the dispute over the Eucharist and the controversy about trina deitas. In the second part, which constitutes the main body of the article, I will focus on the presenta- tion of four sources of controversies in the dispute over predestination, whose inventor and proponent was Gottschalk of Orbais, namely: (i) the concept of God, (ii) the meaning of grace, nature and free will, (iii) the rela- tion of foreknowledge to predestination, and (iv) the doctrine of redemption, i.e., in particular, the relation of justice to mercy. The article is mainly an attempt at an interpretation of the texts of the epoch, mainly by Gottschalk of Orbais1 and his adversary, Hincmar of Reims.2 I will point out the dif- Dr ANDRZEJ P. STEFAŃCZYK — Katedra Historii Filozofii Starożytnej i Średniowiecznej, Wy- dział Filozofii Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego Jana Pawła II; adres do korespondencji: Al. -

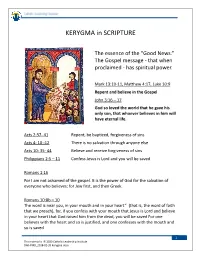

KERYGMA in SCRIPTURE

KERYGMA in SCRIPTURE The essence of the “Good News.” The Gospel message - that when proclaimed - has spiritual power. Mark 13:10-11, Matthew 4:17, Luke 10:9 Repent and believe in the Gospel John 3:16 – 17 God so loved the world that he gave his only son, that whoever believes in him will have eternal life. Acts 2:37- 41 Repent, be baptized, forgiveness of sins Acts 4: 10 -12 There is no salvation through anyone else Acts 10: 35- 44 Believe and receive forgiveness of sins Philippians 2:5 – 11 Confess Jesus is Lord and you will be saved Romans 1:16 For I am not ashamed of the gospel. It is the power of God for the salvation of everyone who believes: for Jew first, and then Greek. Romans 10:8b – 10 The word is near you, in your mouth and in your heart” (that is, the word of faith that we preach), for, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved For one believes with the heart and so is justified, and one confesses with the mouth and so is saved. 1 This material is © 2020 Catholic Leadership Institute DMI-PMD_2018-02-26 Kerygma.docx In Jesus Christ salvation is offered to all people. He is the Way. Our relationship with God was broken (though not cut off). Through Jesus’ complete outpouring of love the relationship is restored. When we accept by faith that Jesus Christ is Lord, Son of the Father, the one who conquered sin and death by love, we enter His death and resurrection (baptism) leading us to salvation. -

Commentary of Rabanus Maurus on the Book of Esther

Draft version 1.1. (c) 2015 The Herzl Institute, Jerusalem All rights reserved Commentary of Rabanus Maurus On the Book of Esther Published 836 Translated from Latin by Peter Wyetzner FOREWORD TO THE EMPRESS JUDITH The Book of Esther, which the Hebrews count among the Writings, contains in the form of mysteries many of the hidden truths of Christ and of the Church—that is, Esther herself, in a prefiguration of the Church, frees the people from danger; and after Haman—whose name is interpreted as wickedness—is killed, she assigns future generations a part in the feast and the festival day. In fact, the translator of the biblical narrative claims that he has copied this book from the documents of the Hebrews, and rendered it straightforwardly and word for word; and yet he did not omit entirely what he found in the Vulgate edition, rather after translating with complete fidelity the Hebrew original he added as an appendix to the end of the book the rest of the passages he found outside it. We have, moreover, explained in an allegorical fashion the material that has been drawn from the Hebrew source; while we have chosen to not to comment upon all the other passages that have been added to it in accordance with the language and the literature of the Greeks, and marked by an obel. But any serious reader can understand well enough the sense of these passages once he has carefully scrutinized the previous ones. And since you, noblest of queens, perceive so well the divine mysteries contained in the interpreted passages, you will no doubt arrive at a proper 1 understanding of the others. -

Theological Interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount

Supplement to Introducing the New Testament, 2nd ed. © 2018 by Mark Allan Powell. All rights reserved. 6.45 Theological Interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount The Early Church In the early church, the Sermon on the Mount was used apologetically to combat Marcionism and, polemically, to promote the superiority of Christianity over Judaism. The notion of Jesus fulfilling the law and the prophets (Matt. 5:17) seemed to split the difference between two extremes that the church wanted to avoid: an utter rejection of the Jewish matrix for Christianity, on the one hand, and a wholesale embrace of what was regarded as Jewish legalism, on the other hand. In a similar vein, orthodox interpretation of the sermon served to refute teachings of the Manichaeans, who used the sermon to support ideas the church would deem heretical. In all of these venues, however, the sermon was consistently read as an ethical document: Augustine and others assumed that its teaching was applicable to all Christians and that it provided believers with normative expectations for Christian behavior. It was not until the medieval period and, especially, the time of the Protestant Reformation that reading the sermon in this manner came to be regarded as problematic. Theological Difficulties Supplement to Introducing the New Testament, 2nd ed. © 2018 by Mark Allan Powell. All rights reserved. The primary difficulties that arise from considering the Sermon on the Mount as a compendium of Christian ethics are twofold. The first and foremost is found in the relentlessly challenging character of the sermon’s demands. Its commandments have struck many interpreters as impractical or, indeed, impossible, particularly in light of what the New Testament says elsewhere about human weakness and the inevitability of sin (including Matt. -

Hrabanus Maurus’ Post-Patristic Renovation of 1 Maccabees 1:1–8

Open Theology 2021; 7: 271–288 Research Article Christian Thrue Djurslev* Hrabanus Maurus’ Post-Patristic Renovation of 1 Maccabees 1:1–8 https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2020-0160 received April 26, 2021; accepted June 01, 2021 Abstract: In this article, I examine Hrabanus Maurus’ exegesis of the opening verses of 1 Maccabees, which preserves a concise account of Alexander the Great’s career. My main goal is to demonstrate how Hrabanus reinterpreted the representation of the Macedonian king from 1 Maccabees. To this end, I employ transfor- mation theory, which enables me to analyze the ways in which Hrabanus updated the meaning of the biblical text. I argue that Hrabanus turned the negative Maccabean narrative of Alexander into a positive representation that was attractive to contemporary readers. I support this argument by focusing on Hrabanus’ recourse to Latin sources, primarily the late antique authors Jerome, Orosius, and Justin, an epitomist of Roman history. I find that Hrabanus challenged Jerome’s interpretations, neutralized much of Orosius’ negative appraisal of Alexander, and amplified the laudatory passages of Justin, which generated a new image of the ancient king. The present article thus contributes to three fields: medieval exegesis of biblical texts, Carolingian reinterpretation of the patristic heritage, and the reception of Alexander the Great. Keywords: Alexander the Great, biblical scholarship, medieval exegesis, “Carolingian Renaissance”, historio- graphy, historical text reuse, transformation theory 1 Prelude: What is the point of reception? Miriam De Cock, the prime mover behind this special issue of Open Theology, invited contributors to reflect on how and why we conduct research into the “reception history”¹ of biblical and patristic heritage. -

Susan K. Roll

Susan K. Roll Hildegard of Bingen: a Doctor of the Church On October 7, 2012, I was privileged to be present at the outdoor papal Mass at the Vatican in which Hildegard of Bingen was officially declared a Doctor of the Church. On October 26 I was even more privileged to be invited to give the opening address at the First International Conference of the Scivias Institut. As a member of the Scivias Institut from the beginning, I was pleased that this conference took place less than three weeks after Hildegard (finally!) received public recognition of her genius and of her contribution both to the Roman Catholic Church and to human creativity and knowledge, both scientific and mystical. In this article I will give some of the background and significance of the title “Doctor of the Church,” then briefly sketch the steps involved in Hildegard’s case. We will mention briefly the loose ends that remain in ascertaining the exact motive. Finally, to expand the context somewhat, we will take a glance at a sampling of contemporary commentaries that illustrates the rather odd situation today in which a medieval nun seems to have become, if not “all things to all people,” then certainly many very different things to various groups of people who want nothing to do with each other. The first point to note is that “Doctor of the Church” is conferred as an honorary title. It is not based on original research nor on the formal academic achievements equivalent to those of a person who holds a university Doctor title today. -

Agrarian Metaphors 397

396 Agrarian Metaphors 397 The Bible provided homilists with a rich store of "agricultural" metaphors and symbols) The loci classici are passages like Isaiah's "Song of the Vineyard" (Is. 5:1-7), Ezekiel's allegories of the Tree (Ez. 15,17,19:10-14,31) and christ's parables of the Sower (Matt. 13: 3-23, Mark 4:3-20, Luke 8:5-15) ,2 the Good Seed (Matt. 13:24-30, Mark 4:26-29) , the Barren Fig-tree (Luke 13:6-9) , the Labourers in the Vineyard (Matt. 21:33-44, Mark 12:1-11, Luke 20:9-18), and the Mustard Seed (Matt. 13:31-32, Mark 4:30-32, Luke 13:18-19). Commonplace in Scripture, however, are comparisons of God to a gardener or farmer,5 6 of man to a plant or tree, of his soul to a garden, 7and of his works to "fruits of the spirit". 8 Man is called the "husbandry" of God (1 Cor. 3:6-9), and the final doom which awaits him is depicted as a harvest in which the wheat of the blessed will be gathered into God's storehouse and the chaff of the damned cast into eternal fire. Medieval scriptural commentaries and spiritual handbooks helped to standardize the interpretation of such figures and to impress them on the memories of preachers (and their congregations). The allegorical exposition of the res rustica presented in Rabanus Maurus' De Universo (XIX, cap.l, "De cultura agrorum") is a distillation of typical readings: Spiritaliter ... in Scripturis sacris agricultura corda credentium intelliguntur, in quibus fructus virtutuxn germinant: unde Apostolus ad credentes ait [1 Cor.