The Perspectives of Nannies on Smart Home Surveillance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Confidentiality Agreement

CLIENT FAMILY CONFIDENTIALITY AND NON-DISCLOSURE AGREEMENT THIS CONFIDENTIALITY AND NON-DISCLOSURE AGREEMENT (the "Agreement") is made and entered into effective on ___________________ 20___ (the "Effective Date"), by and between _________________________ (the “Client Family”) and _______________________ (the “Nanny”). The Client Family and the Nanny agree as follows: 1. Acknowledgement of Private Family Information. The Nanny acknowledges that during his/her engagement with the Client Family, the Nanny will be exposed to the following secret, and confidential items that constitute the Client Family’s private family information ("Private Family Information"): family members’ medical histories and medical conditions, the Client Family’s financial information, Client Family relationships and family dynamics, family passwords, and other matters related to the Client Family. The Nanny expressly acknowledges that if the Private Family Information should become known by any individuals outside the Client Family, such knowledge would result in substantial hardship, loss, damage, and injury to the Client Family. 2. Nondisclosure of Private Family Information & Confidentiality. The Nanny agrees that the Nanny will not, during the term of the Nanny’s engagement with the Client Family or any time thereafter, directly or indirectly disclose the Client Family’s Private Family Information to any entity or any person who is not a member of the Client Family or an employee of Nannies On The Go! The Nanny hereby agrees that she/he: (i) shall not, directly or indirectly, disclose any Private Family Information in any way and (ii) shall limit access to Private Family Information solely to those persons or entities to whom such disclosure is expressly permitted by this Agreement. -

“How the Nanny Has Become La Tata”: Analysis of an Audiovisual

Università degli Studi di Padova Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Lingue Moderne per la Comunicazione e la Cooperazione Internazionale Classe LM-38 Tesi di Laurea “How The Nanny has become La Tata”: analysis of an audiovisual translation product Relatore Laureando Prof. Maria Teresa Musacchio Susanna Sacconi n° matr. 1018252 / LMLCC Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 Contents: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 – THEORY OF AUDIOVISUAL TRANSLATION 1.1 Translation: General concepts 3 1.2 Audiovisual translation 6 1.3 Audiovisual translation in Europe 10 1.4 Linguistic transfer 12 1.4.1 Classification for the current AVT modes 14 1.5 Dubbing vs Subtitling 22 CHAPTER 2 – DUBBING IN ITALIAN AUDIOVISUAL TRANSLATION 2.1 Dubbing: An introduction 27 2.2 A short history of Italian dubbing 31 2.3 The professional figures in dubbing 33 2.4 The process of dubbing 36 2.5 Quality in dubbing 40 CHAPTER 3 – DUBBING: ASPECTS AND PROBLEMS 3.1 Culture and cultural context in dubbing 43 3.2 Dialogues: their functions and their translation in films 47 3.3 Difficulties in dubbing: culture-bound terms and cultural references 51 3.3.1 Culture-bound terms 54 3.3.2 Ranzato: the analysis of cultural specific elements 55 3.4 Translation strategies in dubbing (and subtitling) 59 3.4.1 Other strategies: Venuti’s model and Toury’s laws 63 3.4.2 The choice of strategies 65 3.5 Other translation problems: humour and allocutive forms 67 3.5.1 Humour 67 3.5.2 Allocutive forms 68 3.6 Synchronization and other technical problems 70 3.6.1 Synchronization -

Making and Managing Class: Employment of Paid Domestic Workers in Russia Anna Rotkirch, Olga Tkach and Elena Zdravomyslova Intro

Making and Managing Class: Employment of Paid Domestic Workers in Russia Anna Rotkirch, Olga Tkach and Elena Zdravomyslova This text is published with minor corrections as Chapter 6 in Suvi Salmenniemi (ed) Rethinking class in Russia. London: Ashgate 2012, 129-148. Introduction1 Before, they used to say “everybody comes from the working classes”. I have had to learn these new practices from scratch. I had to understand how to organise my domestic life, how to communicate with the people who I employ. They have to learn this too. (Lidiia, housekeeper) Social class is a relational concept, produced through financial, social and symbolic exchange and acted out in the market, in work places, and also in personal consumption and lifestyle. The relations between employers and employees constitute one key dimension of social class. Of special interest are the contested interactions that lack established cultural scripts and are therefore prone to uncertainties and conflicts. Commercialised interactions in the sphere of domesticity contribute to the making of social class no less than do those in the public sphere. In this chapter, we approach paid domestic work as a realm of interactions through which class boundaries are drawn and class identity is formed. We are interested in how middle class representatives seek out their new class identity through their standards and strategies of domestic management, although we also discuss the views of the domestic workers. As the housekeeper Lidiia stresses in the introductory quotation to this chapter, both employers and employees have to learn new micro-management practices and class relations from scratch. The assertion that class is in continual production (Skeggs 2004) is especially true for the contemporary Russian situation, where stratification grids are loose and class is restructured under the pressure of political and economic changes. -

The Case of Bartu Ben

Transformation of Comedy with Streaming Services: The Case of Bartu Ben Nisa Yıldırım, Independent Scholar [email protected] Volume 8.2 (2020) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2020.300 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract Comedy has always been one of the most popular genres in Turkish cinema and television series. As the distinction between film and series has begun to blur in the post-television era, narratives are transforming according to the characteristics of the new medium. Streaming services targeting niche audience offer more freedom to creators of their content. This article aims to study the comedy series Bartu Ben (Its me, Bartu) which is one of the original series of Turkish streaming service Blu TV, in order to interpret the differences of the series from traditional television comedies, and contribution of streaming services to the transformation of the genre. Keywords: Comedy; streaming services, Turkish cinema; Turkish television series; Bartu Ben; Netflix New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press Transformation of Comedy with Streaming Services: The Case of Bartu Ben Nisa Yıldırım Introduction In the recent era, the distinction between cinematic and televisual narratives has been blurring due to the evolution of these two media with the impact of digital technologies. Streaming services have been threatening cinema and television lately in terms of both production and distribution by creating their original films and series, besides offering wide-ranging archives including films, series, and documentaries from various countries with subtitles and dubbing options. -

The Nanny Network & Sitters' Registry 318-841-6266 (NANNY)

The Nanny Network 841-Nanny (6266) Nanny Application and Agreement Thank you for your interest in The Nanny Network. Please complete the following Nanny application and the Nanny agreement and mail to Jennifer Holloway, Po Box 5824, Shreveport, La 71135. Please attach a recent picture & feel free to attach relevant information to the completed application (resume, etc.). Nanny Application & Agreement Name:____________________________________ Date: ____________________ Work Phone: __________________ Home Phone: _________________________ Cell Phone: _____________________Email: ______________________________ Current Address: __________________________________Zip:_______________ Place of Birth:________________________ D.O.B._________________________ Social Security #: ______________________ Driver’s License #_____________ State: _____________ Exp Date: ___________ Are you a US Citizen?__________ Maiden or other name, middle name____________ ____________________ Questions: 1. Explain your childcare experience and why you enjoy being a nanny. 2. What are your hobbies and areas of interest? 3. How do you describe your personality? 1 Driving/Personal Habits: List all accidents and moving violations in which you were a driver in last 3 years:__________________________________________________________________ Have you ever been convicted of a felony? ____________________________________ Explain:_________________________________________________________________ Do you have your own transportation? __________ Describe: ____________________ If a family -

What Happens When Parents and Nannies Come from Different Cultures? Comparing the Caregiving Belief Systems of Nannies and Their Employers

Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 29 (2008) 326–336 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology What happens when parents and nannies come from different cultures? Comparing the caregiving belief systems of nannies and their employers Patricia M. Greenfield ⁎, Ana Flores, Helen Davis, Goldie Salimkhan UCLA, Department of Psychology and FPR-UCLA Center for Culture, Brain, and Development, United States article info abstract Article history: In multicultural societies with working parents, large numbers of children have caregivers from Available online 8 May 2008 more than one culture. Here we have explored this situation, investigating culturally-based differences in caregiving beliefs and practices between nannies and the parents who employ Keywords: them. Our guiding hypothesis was that U.S. born employers and Latina immigrant nannies may Culture have to negotiate and resolve conflicting socialization strategies and developmental goals. Our Cultural values second hypothesis was that sociodemographics would influence the cultural orientation of Individualism nannies and mother-employers independently of ethnic background. We confirmed both Collectivism hypotheses by means of a small-scale discourse-analytic study in which we interviewed a set of Parental belief system nannies and their employers, all of whom were mothers. From an applied perspective, the Immigrant caregiver Socialization results of this study could lead to greater cross-cultural understanding between nannies and mother-employers and, ultimately, to a more harmonious childrearing environment for children and families in this very widespread cross-cultural caregiver situation. © 2008 Published by Elsevier Inc. 1. Introduction Irving Sigel pioneered the study of parental belief systems (Sigel, 1985; Sigel, McGillicuddy-De Lisi, & Goodnow, 1992). -

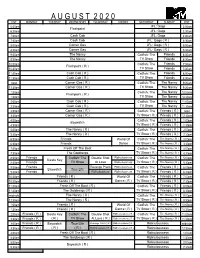

A U G U S T 2 0

A U G U S T 2 0 2 0 EST MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY PST 6:00am JFL: Gags 3:00am Flashpoint 6:30am JFL: Gags 3:30am 7:00am Cash Cab JFL: Gags 4:00am 7:30am Cash Cab JFL: Gags ( R ) 4:30am 8:00am Corner Gas JFL: Gags ( R ) 5:00am 8:30am Corner Gas JFL: Gags ( R ) 5:30am 9:00am The Nanny Catfish: The Friends 6:00am 9:30am The Nanny TV Show Friends 6:30am 10:00am Catfish: The Friends 7:00am Flashpoint ( R ) 10:30am TV Show Friends 7:30am 11:00am Cash Cab ( R ) Catfish: The Friends 8:00am 11:30am Cash Cab ( R ) TV Show Friends 8:30am noon Corner Gas ( R ) Catfish: The The Nanny 9:00am 12:30pm Corner Gas ( R ) TV Show The Nanny 9:30am 1:00pm Catfish: The The Nanny 10:00am Flashpoint ( R ) 1:30pm TV Show The Nanny 10:30am 2:00pm Cash Cab ( R ) Catfish: The The Nanny 11:00am 2:30pm Cash Cab ( R ) TV Show The Nanny 11:30am 3:00pm Corner Gas ( R ) Catfish: The Friends ( R ) noon 3:30pm Corner Gas ( R ) TV Show ( R ) Friends ( R ) 12:30pm 4:00pm Catfish: The Friends ( R ) 1:00pm Baywatch 4:30pm TV Show ( R ) Friends ( R ) 1:30pm 5:00pm The Nanny ( R ) Catfish: The Friends ( R ) 2:00pm 5:30pm The Nanny ( R ) TV Show ( R ) Friends ( R ) 2:30pm 6:00pm Friends World Of Catfish: The The Nanny ( R ) 3:00pm 6:30pm Friends Dance TV Show ( R ) The Nanny ( R ) 3:30pm 7:00pm Fresh Off The Boat Catfish: The The Nanny ( R ) 4:00pm 7:30pm The Goldbergs TV Show ( R ) The Nanny ( R ) 4:30pm 8:00pm Friends Catfish: The Double Shot Ridiculousness Catfish: The The Nanny ( R ) 5:00pm Siesta Key 8:30pm Friends TV Show At Love Ridiculousness -

Nanny Packet

Guidelines for Screening Nannies and Babysitters Check References • Ask for references from people who know the applicant. • Listen carefully for tone. • Elicit examples to support answers to interview questions. • Among other questions, ask, “Would you hire this person again to care for your children?” Do background checks (for applicants 18 years and older) • Request a background check through your local police department or online. • Check the National Sex Offender Registry to see if the applicant has been convicted of sexual assault. Check driving records • If your nanny or babysitter will be transporting your children, check his or her driving record through your local Department of Motor Vehicles. Conduct an interview • Get to know applicants by asking open ended and thought-provoking questions. • Include questions about child sexual abuse prevention—e.g., Have you ever received sexual abuse prevention education? What would you do if my child asked you to keep a secret from me? How would you respond to my children grabbing each other’s private parts while bathing? • Listen carefully for how the person responds to each question and watch body language— i.e., Is the individual warm and responsive? Does the person give examples and accept responsibility for her/his actions? • Listen to your intuition! Your gut instinct is the best and most qualified interviewer! If you have a nagging or ambivalent feeling, or find that you are talking yourself into liking the applicant, she/he isn’t the right person for the job. Get a signed agreement (see page two for sample) Conduct a trial run • Ask the sitter or nanny to supervise your children doing an activity and observe how she/he interacts with your children. -

Sample Nanny Contract Is Designed for General Informational Purposes Only

This Sample Nanny Contract is designed for general informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide, and does not constitute legal or other professional advice by Poppins Payroll, LLC. You should consult with a lawyer if you intend to enter into a legal contract. Nanny Agreement This Nanny Agreement (this “Agreement”) is entered on _______________, 20___ between __________________________ (the “Parent(s)”) and __________________ (the “Nanny”) whereby the Nanny agrees to provide care for the child or children identified below (the “Kid(s)”) commencing on _______________, 20___ in accordance with the terms and conditions set forth below: 1. Personal Information. a. Parent Information. Address: _________________________________________ City: ________________ State: ____ Zip Code: __________ Phone Numbers: ___________________________________ _________________________________________________ b. Kid Information. _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ c. Nanny’s Information. Address: _________________________________________ City: ________________ State: ____ Zip Code: __________ Phone Numbers: ___________________________________ _________________________________________________ d. Worksite Address. Same as the Parent’s address above. Address: _________________________________________ City: ________________ State: ____ Zip Code: __________ 2. Work Hours and Location. -

Live in Nanny P (^Are.Ccni Care.Com Boca Raton, FL Live in Nanny Via Care.Com

Sign in Near Boca Raton, FL JOBS SAVED ALERTS Title Location Date posted Type Company type more All Nanny Bilingual Housekeeper Sitter Live In Nanny P (^are.ccni Care.com Boca Raton, FL Live In Nanny via Care.com 0 Over 1 month ago $ 15 an hour Care.com ii.' Boca Raton, FL Nanny Job, Boca Raton 1 Spanish □ speaking live in nanny for twin boys GreatAuPair Apply on Care.com Boca Raton, FL via GreatAuPair 0 4 days ago Full-time 0 Over 1 month ago $ 15 an ho Bilingual Live In Nanny Needed For |Z| About the Job We are looking for ^omccin Infant Twin Boys In Boca Raton help with our 5-year-old and 2-yec Care.com well. Thank you! Job basics How Boca Raton. FL $15.00/hour Who we're looking f« via Care.com 3 years * 1 Child aged 4 - 6 years 3-6pm, 6-9pm • Wed: 6-9am, 9-12 (^11 days ago $ 15-25 an hour 12pm, 12-3pm, 3-6pm, 6-9pm • Fri: 5-9ar LIve-in/Llve-Out Nanny Needed □ 9am. Pragathi.com User 9-12pm. 12-3pm. 3-6pm. 6-9pm Boca Raton, FL via Pragathi.com 0 Over 1 month ago (ft Full-time O Report this listing Live-in Nanny P Care.com H Healthy Smiles Dental Indeed Turn on email alerts for this search 4.2 - 1,536 reviews Find jobs Company reviews Find salaries Upload your resume Signin Employers / Post job Full-time Live-in Nanny London Bee Premier Nanny Service - Wellington, PL Live in Where Boca Rator^fb,000 - $110,000 a year Advanced Jc Apply Now Date Posted ▼ within 50 miles Salary Job Type ▼ Location ▼ Company » Experience Level Save jobs and view them from any computer. -

Experimental Stories Anna/Paul Couldn't Wait for the Babysitter To

Experimental Stories Anna/Paul couldn't wait for the babysitter to arrive. The babysitter was a young boy/girl/teenager who always took the job seriously and got along with Anna/Paul very well. While the parents got ready to leave, Anna/Paul waited anxiously. Anna/Paul loved watching her/his parents get ready to go out. Tonight there was a big dinner party. Anna/Paul wanted her/his parents to hurry up and go out. The babysitter found himself/herself humming while walking up to the door. Was Anna/Paul going out to dinner with her/his parents? Joan/Bill was administering the final exam at the Beauty School. One beautician was an inexperienced man/woman/person who had dyed the client's hair purple. When the haircut was finished, Joan/Bill tried to maintain a straight face. Joan/Bill always had a hard time with this part of her/his job. The job required a good deal of tact and sensitivity. Joan/Bill felt badly when someone wasn't happy with how they looked. The beautician steeled himself/herself before letting the client look in a mirror. Did the beautician dye the client's hair purple? Beth/Eric watched the gypsies dancing at the fair. One gypsy, an attractive man/woman/person wearing a yellow shirt, waved his/her scarf and pulled a coin from behind Beth's/Eric’s ear. As always, Beth/Eric was entranced by the performance. Beth/Eric loved watching the elaborate routines. The dancing was often accompanied by loud music. Beth/Eric also loved the bright costumes. -

Fran Drescher and "The Nanny" Co-Star Charles Shaughnessy to Reunite for the Season Finale of TV Land's "Happily Divorced"

Fran Drescher and "The Nanny" Co-Star Charles Shaughnessy to Reunite for the Season Finale of TV Land's "Happily Divorced" SANTA MONICA, Calif., July 26, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Charles Shaughnessy ("The Nanny," "Mad Men"), who played Fran's employer-turned-husband in the popular sitcom, "The Nanny," guest stars as Gregory, a guy that both Fran and her ex-husband Peter (John Michael Higgins) want to date in the season finale of "Happily Divorced." To date, the series is averaging over 2.2 million viewers every week. Last week, "Happily Divorced" was renewed for a second season of 12 episodes. Also making a special guest appearance this season will be Fran's nosy and overbearing mother from "The Nanny," Renee Taylor, who will play Marilyn, an old friend of Fran's mother, Dori (Rita Moreno). Additionally, Angie Everhart guest stars as the sister of Fran's ex-boyfriend, Elliot (D.W. Moffett), Lou Diamond Phillips will appear as a man that chooses Judi (Tichina Arnold) over Fran, and Jennifer Holliday (Broadway's "Dreamgirls") will guest star as herself. Most recently, Ian Ziering ("Beverly Hills, 90210") guest-starred as a handsome support group leader who helps Fran realize that she has not moved on from her divorce. TV Land's "Happily Divorced" Guest Star Episode Descriptions: Wednesday 7/27/11 at 10:30pm "Someone Wants Me" Fran runs into Elliot with a beautiful woman and realizes she still isn't over him, which prompts her to try online dating. Despite many matches, she can't stop thinking about Elliot, so she decides to pursue him again - but it leads to an awkward situation.