Real Progress, Real Challenges: Working Toward Salmon Recovery and Watershed Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

*S*->^R*>*:^" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2085-A R^C I V"*, *>*S*->^R*>*:^

Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Provenance of the Raging River Formation (Early? and Middle Eocene), King County, Washington U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2085-A r^c i V"*, *>*s*->^r*>*:^ l1^ w >*': -^- ^^1^^"g- -'*^t» *v- »- -^* <^*\ ^fl' y tf^. T^^ ?iM *fjf.-^ Cover. Steeply dipping beds (fluvial channel deposits) of the Eocene Puget Group in the upper part of the Green River Gorge near Kanaskat, southeastern King County, Washington. Photograph by Samuel Y. Johnson, July 1992. Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Provenance of the Raging River Formation (Early? and Middle Eocene), King County, Washington By Samuel Y. Johnson and Joseph T. O'Connor EVOLUTION OF SEDIMENTARY BASINS CENOZOIC SEDIMENTARY BASINS IN SOUTHWEST WASHINGTON AND NORTHWEST OREGON Samuel Y. Johnson, Project Coordinator U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2085-A A multidisciplinary approach to research studies of sedimentary rocks and their constituents and the evolution of sedimentary basins, both ancient and modern UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, Samuel Y. Stratigraphy, sedimentology, and provenance of the Raging River Formation (Early? and Middle Eocene), King County, Washington/by Samuel Y. Johnson and Joseph T. O'Connor. p. cm. (U.S. Geological Survey bulletin; 2085) (Evolution of sedimentary basins Cenozoic sedimentary basins in southwest Washington and northwest Oregon; A) Includes bibliographical references. -

2. If the Following Recommendation Is Adopted by the King County

122-86-R Page 7 2. If the following recommendation is adopted by the King County Council, it would meet the purposes and intent of the King County Comprehensive Plan of 1985, and would be consistent with the purposes and provisions of the King County zoning code, particularly the purpose of the potential zone, a s set forth in KMngpm^|o 60 . The conditions recommended below are reasonable and necessary to meet the policies of the King County Comprehensive Plan which are specifically intended to minimize the impacts of quarrying and mining activities on adjacent and nearby land uses. 3. Approval of reclassification of the approximately 25.6 acre property adjacent to the south of the existing quarry would be consistent with the intent of the action taken by King County at the time of the Lower Snoqualmie Valley Area Zoning Study (Ordinance 1913). This reclassification will not be unreasonably incompatible with nor detrimental to surrounding properties and/or the general public. It will enable the applicant to move quarry operations to the south and southwest, which is no longer premature. 4. Reclassification of the 25.6 acre parcel adjacent to the south of the existing quarry meets the requirements of King County Code Section 20.24.190, in that the said parcel is potentially zoned for the proposed use. Reclassification of the 5.4 acre parcel to the east and of the 4.5 acre parcel to the west of the existing quarry site would be inconsistent with KCC 20.24.190. RECOMMENDATION: Approve Q-M-P for the 25.6 acre parcel adjacent to the south of the existing Q-M area, subject to the conditions set forth below, and deny reclassification of the 5.4 acres to the east (Lot 4 of King County Short Plat No. -

Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin July 2021

Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin July 2021 Prepared for: Snohomish River Basin Salmon Recovery Technical Committee Prepared by: Josh Kubo, Andrew Miller, and Emily Davis. King County Water Land and Resources Division. Acknowledgements: Project Team: Emily Davis, Elissa Ostergaard, Kollin Higgins, Andrew Miller, and Josh Kubo Reviewers: Matt Baerwalde, Dave Beedle, Keith Binkley, Steve Britsch, Curtis DeGasperi, Aimee Fullerton, Kollin Higgins, Heather Kahn, Janne Kaje, Frank Leonetti, Kurt Nelson, Elissa Ostergaard, Colin Wahl. Recommended Citation: Kubo, J., A. Miller, and E. Davis. 2021. Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin. King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks, Water Land and Resources Division, Seattle, WA. July, 2021 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 3 Why is water temperature important for salmon recovery? ................................................................... 6 Drivers of Water Temperature ............................................................................................................... 10 Human Alterations to Aquatic Thermal Regimes ................................................................................... 16 Water Temperature Standards in the Snohomish River Basin ............................................................... 21 Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin ............................................................. -

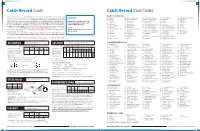

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142. -

Central Puget Sound Low Flow Survey

CENTRAL PUGET SOUND LOW FLOW SURVEY Prepared for The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife By John Lombard Steward and Associates and Dave Somers Dave Somers Consulting FINAL REPORT November 30, 2004 Steward and Associates 120 Avenue A, Suite D Snohomish, Washington 98290 Tel (360) 862-1255 Fax (360) 563-0393 www.stewardandassociates.com Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................................. 1 Definition of Low Flow Problem ........................................................................................... 2 Adopted Regulatory Instream Flows .................................................................................... 6 Climate Change....................................................................................................................... 7 Quantification of Instream Flow Needs ................................................................................ 7 Recommendations.................................................................................................................10 Summary Reports by WRIA................................................................................................ 12 STILLAGUAMISH (WRIA 5)........................................................................................... 12 Environmental Setting .................................................................................................... 12 Draft Stillaguamish – WRIA 5 Chinook Salmon Recovery Plan -

Stratigraphy of Eocene Rocks in a Part of King County, Washington

State of Washington ALBERT D. ROSELLINI, Governor Department of Conservation EARL COE, Director DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY MARSHALL T. HUNTTING, Supervisor Report of Investigations No. 21 STRATIGRAPHY OF EOCENE ROCKS IN A PART OF KING COUNTY, WASHINGTON by JAMES D. VINE U. S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California Prepared Cooperatively by the United States Geological Survey STAT£ PRINTING PLANT. OLYMPIA, WASH. 1962 For sale by Department of Conservation, Olympia, Washington. Price, 50 cents. ~ 3 CONTENTS Page Abstract . 1 Introduction . • . 2 Facies relations within the Puget Group . 4 Raging River Formation . 7 Puget Group . 12 Tiger Mountain Formation . 12 Tukwila Formation ... .. .... ... ... .. .. .. .. ..... .. .. 14 Renton Formation . 16 Summary ... .... ... ....... .. .. .. .. ..... ....... .... 17 References cited . 20 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map of part of King County, Washington, showing location of areas described . 2 2. Correlation chart showing Puget Group and equivalent forma- tions . 3 3. Stratigraphic column and index map showing position of fossil localities, King County, Washington .... ......... .......... 10 TABLES Table 1. Fossil invertebrates from the Raging River Formation, King County, Washington 9 2. Foraminiferal species from fae Raging River Formation . 11 3. Fossil leaves from the Tiger Mountain Format:on, King County, Washington . 13 4. Fossil leaves from the Tukwila Formation, King County, Wash- ington ....................... ..... ... .... ................. 15 STRATIGRAPHY OF EOCENE ROCKS IN A PART OF KING COUNTY, WASHINGTON1 By JAMrs D. VINE2 ABSTRACT Marine rocks of Eo::ene age in part of King County, Washington, are over lain by a sequence of nonmarine rocks of Eocene age including both volcanic and nonvolcanic types. The volcanic type is c~ar acterized by andesitic tuff breccia and epiclastic sandstone, whereas the nonvolcanic type is characterized by arkosic micaceous sandstcne, siltstone, and coal beds. -

The Effects of Placed Wood on the Physical Habitat and Thermal Conditions in the Raging River, WA

The Effects of Placed Wood on the Physical Habitat and Thermal Conditions in the Raging River, WA January 2017 Alternate Formats Available The Effects of Placed Wood on the Physical Habitat and Thermal Conditions in the Raging River, WA Prepared for: The Snoqualmie Watershed Forum and the King County Flood Control District Submitted by: Kate Macneale King County Water and Land Resources Division Department of Natural Resources and Parks Funded by: This study was funded by the Snoqualmie Watershed Forum through Cooperative Watershed Management grant funds and by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Cooperative Water Program. The Effects of Placed Wood on the Physical Habitat and Thermal Conditions in the Raging River, WA Acknowledgements We thank Ray Timm for developing the original proposal, for obtaining grant funding for King County, and for providing support throughout the study. We thank the following King County Water and Land Resources Division staff for their technical or field help: Bob Pendergast, Josh Kubo, Andrew Miller, Dan Lantz, Chris Gregersen, Chris Knutson, Jo Wilhelm, Kay Kitamura, and Ken Rauscher. We thank Andrew Gendaszek of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) for securing matching funds from the USGS Cooperative Water Program. We also thank Andrew Gendaszek and Chad Opatz for their collaboration, and for the operation of the fiber-optic distributed temperature sensor. We thank Josh Kubo, Josh Latterell, Andrew Miller, Beth leDoux, Kate O’Laughlin, and Deb Lester of King County Water and Land Resources Division for their helpful discussions and careful reviews of the report. Citation King County. 2016. The effects of placed wood on the physical habitat and thermal conditions in the Raging River, WA. -

2019-21 Capital Budget Proposed Compromise 2020 Local and Community Projects (Dollars in Thousands)

Capital Budget Proposed Compromise Senate Floor Striking Amendment to SHB 1102 (S-4578.1/19) April 27, 2019 Senate Committee Services Office of Program Research Debt Limit Washington State has a constitutional debt limit. The State Treasurer may not issue any bonds that would cause the debt service (principal and interest payments) on any new and existing bonds to exceed this limit. Under a constitutional amendment approved by the voters in 2012, the state debt limit is currently 8.25 percent of the average of the prior six years’ general state revenues, defined as all unrestricted state tax revenues. This limit is reduced to 8 percent beginning on July 1, 2034. Bond Capacity A model administered by the State Treasurer’s Office is used to calculate the available bond capacity for the current budgeting period and for future biennial planning purposes. The model calculates the actual debt service on outstanding bonds and is used to estimate future debt service based on certain assumptions including revenue growth, interest rates, rate of repayment, rate of bond issuance, and other factors. For the 2019–21 biennium, projected bond capacity is $3.2 billion. This bond capacity incorporates the 2019 March Economic and Revenue forecast and estimated increases in general state revenue from legislative actions. In addition, there is capacity remaining from bonds previously authorized, including from the Streamflow Restoration program, from the 2018 Supplemental Capital Budget, and from adjusting funding in the 2019 Supplemental Capital Budget. Appropriations for 2019–21 and 2019 Supplemental Budget After the enacted 2018 Supplemental Capital Budget, there was $10.8 million in bond capacity remaining. -

Water Temperature Profiles for Reaches of the Raging River During Summer Baseflow, King County, Western Washington, July 2015

Prepared in cooperation with King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks Water Temperature Profiles for Reaches of the Raging River during Summer Baseflow, King County, Western Washington, July 2015 Data Series 983 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Photograph showing large wood placements in Raging River, King County, Washington. Photograph by Andrew Gendaszek, U.S. Geological Survey, March 19, 2014. Water Temperature Profiles for Reaches of the Raging River during Summer Baseflow, King County, Western Washington, July 2015 By Andrew S. Gendaszek and Chad C. Opatz Prepared in cooperation with King County Department of Natural Resource and Parks Data Series 983 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Gendaszek, A.S., and Opatz, C.C., 2016, Water temperature profiles for reaches of the Raging River during summer baseflow, King County, western Washington, July 2015: U.S. -

Raging River Natural Area

RAGING RIVER NATURAL AREA (Leong Property) FOREST STEWARDSHIP PLAN Property Location 52.5 acres on the east side of Raging River, 2.3 miles south of the Snoqualmie River Bridge in Fall City. Legal Description King County, WA Portion NW¼ Sec. 27, T24N, R7E and Portion E½ Sec. 28,T24N, R7E Additional legal(s) on: Assessor’s Tax Parcel ID#: 272407-9024-07, 272407-9028-03, 282407-9025-08, 282407-9032-06 (See Also Attachment A) Plan Prepared By King County Resource Professionals: Bill Loeber, Forester Kirk Anderson, WRIA 7 Basin Steward Tom Eksten, Trails Coordinator Chuck Lennox, Interpretive Programs Coordinator March 2001 Forest Legacy Program Acquisition This Forest Stewardship Plan is being prepared to comply with the grant requirements of the US Forest Service Forest Legacy Program. Forest Legacy funds were used to purchase the development rights from the portion of the property referred to as the “Forest Conservation Easement ” in the legal description and on the property map. However, in order to develop appropriate resource management strategies, King County felt the plan should cover all parcels within the site. Consistent with the requirements of the Forest Legacy Program, a conservation easement is recorded on the property concurrent with the acquisition of the development rights. Any revision to the Forest Stewardship Plan would need to be consistent with the purposes and requirements of the Forest Legacy Program and approved by the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page FOREST STEWARDSHIP VISION -

Cultural Resources Report Cover Sheet

CULTURAL RESOURCES REPORT COVER SHEET DAHP Project Number: (Please contact the lead agency for the project number. If associated to SEPA, please contact [email protected] to obtain the project number before creating a new project.) Author: Alicia Valentino and F. Scott Pierson Title of Report: Ronnei-Raum House Cultural Resources Assessment, Fall City, Washington Date of Report: June 12, 2020 County(ies): King Section: 15 Township: 24N Range: 7E Quad: Fall City, WA 7.5-minute Acres: 0.32 PDF of report submitted (REQUIRED) Yes Historic Property Inventory Forms to be Approved Online? Yes No Archaeological Site(s)/Isolate(s) Found or Amended? Yes No TCP(s) found? Yes No Replace a draft? Yes No Satisfy a DAHP Archaeological Excavation Permit requirement? Yes # No Were Human Remains Found? Yes DAHP Case # No DAHP Archaeological Site #: Revised 9-26-2018 Ronnei-Raum House Cultural Resources Assessment, Fall City, Washington Prepared by: Alicia Valentino, Ph.D., RPA F. Scott Pierson, B.A. June 12, 2020 WillametteCRA Report Number 20-14 Legal description: T24N R7E S15 County: King USGS quad: Fall City Project Acreage: 0.32 Acres Surveyed: 0.32 Findings: None Fieldnotes: on file, WillametteCRA Curation: None Ronnei-Raum House Cultural Resources Assessment Fall City, Washington Prepared by: Alicia Valentino, Ph.D., RPA F. Scott Pierson, B.A. June 12, 2020 Prepared for: Historic Seattle Willamette Cultural Resources Associates, Ltd. Portland and Seattle WillametteCRA Report Number 20-14 Table of Contents Introduction and Project Description ............................................................................................................ -

Taylor Mountain Public Use Plan

Part I – Introduction and Planning Guidelines Introduction The Taylor Mountain Public Use Plan and Trails Assessment is a partnership planning project between the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (WADNR), King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks (KCDNR&P), and the City of Seattle – Cedar River Watershed. The plan is to review and determine appropriate low-impact recreational opportunities in the greater Taylor Mountain Area. Approximately 54% of the state’s population is located within an hour’s drive to the planning area. From 1990 to 2000, recreational use at Tiger Mountain State Forest increased 48%. Due to the heavy recreational use at Tiger Mountain State Forest and the public lands located along the entire Mountains to Sound Greenway/I-90 corridor, this study and resultant plan are intended to help disperse recreational use and demand to the south and the east of I-90 and State Route 18 (SR 18). Taylor Mountain is becoming more popular for low-impact recreational use. This plan addresses public use and access concerns, trail conditions and damage to natural resources across the entire planning area and across jurisdictional boundaries. It further addresses existing trail conditions and needed trail improvements, trail circulation issues and ecological impacts of recreational use. This study was funded by an Interagency Committee for Outdoor Recreation – Nonhighway and Off-road Vehicle Activities (IAC – NOVA) Grant Planning Area Description The Taylor Mountain Public Use Planning Area is located south and east of Tiger Mountain, south of I-90 and east of SR 18, between the communities of Hobart and North Bend in eastern King County (see Figure 1).