Aquatic Habitat Conditions in the Lower Snoqualmie, Tolt, and Raging Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Riverine Thermal Regimes on Stream Networks Insights Into

Ecological Indicators 84 (2018) 11–26 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Indicators journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolind Original Articles Monitoring riverine thermal regimes on stream networks: Insights into MARK spatial sampling designs from the Snoqualmie River, WA ⁎ Amy Marshaa,b, , E. Ashley Steelb, Aimee H. Fullertonc, Colin Sowderd,b a School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98195 USA b Statistics, PNW Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 400 N 34th Street, Suite 201, Seattle, WA, 98103, USA c Northwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries Service,2725 Montlake Blvd. East, Seattle, WA, 98112 USA d Department of Statistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98195 USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Understanding, predicting, and managing the spatiotemporal complexity of stream thermal regimes requires Water temperature monitoring strategies designed specifically to make inference about spatiotemporal variability on the whole SSNM stream network. Moreover, monitoring can be tailored to capture particular facets of this complex thermal Streams landscape that may be important indicators for species and life stages of management concern. We applied Rivers spatial stream network models (SSNMs) to an empirical dataset of water temperature from the Snoqualmie River Spatial autocorrelation watershed, WA, and use results to provide guidance with respect to necessary sample size, location of new sites, Monitoring and selection of a modeling approach. As expected, increasing the number of monitoring stations improved both predictive precision and the ability to estimate covariates of stream temperature; however, even relatively small numbers of monitoring stations, n = 20, did an adequate job when well-distributed and when used to build models with only a few covariates. -

A Good Turn for the Tolt

A GGoodood TurnTurn forfor thethe TTolt:olt: LLeveeevee SSetback/Salmonetback/Salmon HHabitatabitat PProjectroject Frequently Asked Questions Question: Why restore salmon habitat? Answer: Salmon are an enduring symbol of the Pacifi c Northwest, providing direct and indirect benefi ts to our culture, economy, and environment. Healthy salmon populations mean that our region is a healthy place to live and work. Salmon have been integral to Native American culture for centuries, and federal treaties assure the tribes continued access to healthy salmon stocks. The federal government lists Puget Sound Chinook salmon, as well as bull trout, as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This means they are likely to become endangered, or at a high risk of extinction, if steps to protect them are not taken soon. Science indicates that land uses affecting the salmon’s freshwater habitat are among the primary causes for the species’ decline. Although the federal government administers the ESA, everyone shares the responsibility to protect these animals, because everyone depends on healthy land and water resources. Local governments throughout Puget Sound are implementing projects to protect and restore salmon habitat. Question: Can the Tolt River really be restored? Answer: To prevent the river from fl ooding adjacent lands, levees were constructed along the lower Tolt in the 1940s. While partially successful, the levees dramatically changed the river’s behavior and fi sh habitat. In a more natural condition, the river is connected to its fl oodplain, has more room to move back and forth, and creates meander bends and split channels. A natural river also captures large pieces of wood from trees along the bank. -

*S*->^R*>*:^" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2085-A R^C I V"*, *>*S*->^R*>*:^

Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Provenance of the Raging River Formation (Early? and Middle Eocene), King County, Washington U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2085-A r^c i V"*, *>*s*->^r*>*:^ l1^ w >*': -^- ^^1^^"g- -'*^t» *v- »- -^* <^*\ ^fl' y tf^. T^^ ?iM *fjf.-^ Cover. Steeply dipping beds (fluvial channel deposits) of the Eocene Puget Group in the upper part of the Green River Gorge near Kanaskat, southeastern King County, Washington. Photograph by Samuel Y. Johnson, July 1992. Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Provenance of the Raging River Formation (Early? and Middle Eocene), King County, Washington By Samuel Y. Johnson and Joseph T. O'Connor EVOLUTION OF SEDIMENTARY BASINS CENOZOIC SEDIMENTARY BASINS IN SOUTHWEST WASHINGTON AND NORTHWEST OREGON Samuel Y. Johnson, Project Coordinator U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 2085-A A multidisciplinary approach to research studies of sedimentary rocks and their constituents and the evolution of sedimentary basins, both ancient and modern UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, Samuel Y. Stratigraphy, sedimentology, and provenance of the Raging River Formation (Early? and Middle Eocene), King County, Washington/by Samuel Y. Johnson and Joseph T. O'Connor. p. cm. (U.S. Geological Survey bulletin; 2085) (Evolution of sedimentary basins Cenozoic sedimentary basins in southwest Washington and northwest Oregon; A) Includes bibliographical references. -

2. If the Following Recommendation Is Adopted by the King County

122-86-R Page 7 2. If the following recommendation is adopted by the King County Council, it would meet the purposes and intent of the King County Comprehensive Plan of 1985, and would be consistent with the purposes and provisions of the King County zoning code, particularly the purpose of the potential zone, a s set forth in KMngpm^|o 60 . The conditions recommended below are reasonable and necessary to meet the policies of the King County Comprehensive Plan which are specifically intended to minimize the impacts of quarrying and mining activities on adjacent and nearby land uses. 3. Approval of reclassification of the approximately 25.6 acre property adjacent to the south of the existing quarry would be consistent with the intent of the action taken by King County at the time of the Lower Snoqualmie Valley Area Zoning Study (Ordinance 1913). This reclassification will not be unreasonably incompatible with nor detrimental to surrounding properties and/or the general public. It will enable the applicant to move quarry operations to the south and southwest, which is no longer premature. 4. Reclassification of the 25.6 acre parcel adjacent to the south of the existing quarry meets the requirements of King County Code Section 20.24.190, in that the said parcel is potentially zoned for the proposed use. Reclassification of the 5.4 acre parcel to the east and of the 4.5 acre parcel to the west of the existing quarry site would be inconsistent with KCC 20.24.190. RECOMMENDATION: Approve Q-M-P for the 25.6 acre parcel adjacent to the south of the existing Q-M area, subject to the conditions set forth below, and deny reclassification of the 5.4 acres to the east (Lot 4 of King County Short Plat No. -

1. Puget Sound Rivers and Salmon Recovery

1. Puget Sound Rivers and Salmon Recovery David R. Montgomery, Derek B. Booth, and Susan Bolton A symposium on Restoration of Puget Sound Rivers at the spring 2000 meeting of the Society for Ecological Restoration’s Northwest chapter pre- sented an opportunity to synthesize regional expertise on river and stream restoration into a single volume. Largely drawn from presentations at the conference, the chapters of this book span a wide range of backgrounds and interests, including public policy, riparian forestry, stream ecology, hydrol- ogy, geomorphology, geology, and civil engineering. Chapters of the book proceed from geological and geomorphological controls on river and stream characteristics and dynamics, to the biological aspects of river systems in the region, to chapters that address social constraints and the application of flu- vial geomorphology, civil engineering, riparian ecology, and aquatic ecol- ogy to regional river restoration projects and programs. While we recognize that the material presented herein could not be comprehensive given the broad scope of the subject, these chapters have been selected to provide a com- pilation of state-of-the-art considerations and approaches for developing river restoration programs. The recent listing of various runs and stocks of Pacific salmon under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) has focused national attention on the condi- tion of rivers and streams of the Pacific Northwest (PNW). In the Puget Sound region, recent ESA listings triggered statewide efforts to improve channel habitat involving ongoing expenditure of many millions of dollars annually and resulted in preparation of a “Statewide Strategy to Recover Salmon” by the Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office (GSRO 1999). -

Assessment of Summer Temperatures and Feasibility and Design of Improved Adult Chinook Salmon Thermal Refuge Habitat in the Sammamish River

Assessment of Summer Temperatures and Feasibility and Design of Improved Adult Chinook Salmon Thermal Refuge Habitat in the Sammamish River Prepared for: Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division Auburn WA Prepared by: R2 Resource Consultants 15250 NE 95th St 1998 Photo by Roger Tabor, USFWS Adult Chinook Holding in Pool Near Marymoor Park Redmond WA 98052 December 30, 2010 Assessment of Summer Temperatures and Feasibility and Design of Improved Adult Chinook Salmon Thermal Refuge Habitat in the Sammamish River Prepared for: Holly Coccoli, Project Manager Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division Auburn WA Prepared by: Paul DeVries PhD, PE Clair Yoder PE Chiming Huang PhD, PE Glen Anderson PE Karee Oliver Mike Cooksey R2 Resource Consultants Inc. 15250 NE 95th St Redmond WA 98052 December 30, 2010 Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division Sammamish River Thermal Refuge Habitat CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ XIII 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 1.1 OVERVIEW OF FLOW AND TEMPERATURE CONDITIONS AFFECTING ADULT CHINOOK SALMON IN THE SAMMAMISH RIVER ...................................................................................3 1.1.1 Review of Flow and Temperature Gage Data .........................................................3 1.1.2 Synopsis of Other Relevant Water Quality Studies ..............................................14 -

Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin July 2021

Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin July 2021 Prepared for: Snohomish River Basin Salmon Recovery Technical Committee Prepared by: Josh Kubo, Andrew Miller, and Emily Davis. King County Water Land and Resources Division. Acknowledgements: Project Team: Emily Davis, Elissa Ostergaard, Kollin Higgins, Andrew Miller, and Josh Kubo Reviewers: Matt Baerwalde, Dave Beedle, Keith Binkley, Steve Britsch, Curtis DeGasperi, Aimee Fullerton, Kollin Higgins, Heather Kahn, Janne Kaje, Frank Leonetti, Kurt Nelson, Elissa Ostergaard, Colin Wahl. Recommended Citation: Kubo, J., A. Miller, and E. Davis. 2021. Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin. King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks, Water Land and Resources Division, Seattle, WA. July, 2021 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 3 Why is water temperature important for salmon recovery? ................................................................... 6 Drivers of Water Temperature ............................................................................................................... 10 Human Alterations to Aquatic Thermal Regimes ................................................................................... 16 Water Temperature Standards in the Snohomish River Basin ............................................................... 21 Water Temperature Conditions in the Snohomish River Basin ............................................................. -

Q4 2018 News Magazine

w w sdukNewsalbix Magazine Issue #2 Winter Quarter 2018 In This Issue: • 20th Anniversary of Re-Recognition • Celebrating Tribal Heritage With The Snoqualmie Valley YMCA • Snoqualmie Welcomes N8tive Vote • And More! Call For Submissions Tribal Member News Here we present to you, the second issue of the new quarterly news magazine. We hope you are enjoying Northwest Native American Basketweavers Association reading the content and seeing the photos that this new, extended magazine format allows us to publish! Linda Sweet Baxter, Lois Sweet Dorman and McKenna Sweet Dorman traveled But as much as we like to write and enjoy creating content, we want this magazine to belong to all Tribal to Toppenish, WA to attend the Northwest Native American Basketweavers Members. If you have a story to tell or an item of news, art or photography you want to share please contact Association’s (NNABA) 24th annual gathering in October. us. We would be very happy to include your material in an upcoming issue of the magazine. They sat with Laura Wong-Whitebear, who was teaching coil weaving with Our e-mail address and our mailing address can be found in the blue box right below this space. You can hemp cord and waxed linen. contact us using either one. Please Welcome Rémy May! Christopher Castleberry and his wife Audrey Castleberry are honored to present their newest family member, Rémy May. Table of Contents sdukwalbixw News Magazine Staff Born on Nov. 27th she is 8lbs 6oz and 20.5 inches tall. Call For Submissions 2 Michael Brunk Here, dad and daughter are pictured at Snoqualmie Falls. -

Real Progress, Real Challenges: Working Toward Salmon Recovery and Watershed Health

July 2016 SNOQUALMIE WATERSHED FORUM TEN-YEAR STATUS REPORT 2005-2015 Real Progress, Real Challenges: Working Toward Salmon Recovery and Watershed Health The Snoqualmie Watershed Forum is a partnership of elected officials, citizens and representatives from conservation organizations supporting salmon recovery and ecological health in the Snoqualmie and South Fork Skykomish Watersheds. Member governments include King County, the Snoqualmie Tribe, Tulalip Tribes, the cities of Duvall, Carnation, North Bend and Snoqualmie, and the Town of Skykomish. Since 1998, the Forum and its many partner organizations have worked to protect and restore salmon habitat and improve overall watershed health through collaborative action. From 1998-2005, the Forum played a key role in developing the Snohomish River Basin Salmon Conservation Plan, and since that time has led its implementation in the King County portion of the basin. The Forum’s work is funded by contributions from its member governments, as well as grants from the King County Flood Control District. In 2015, Forum member governments signed an interlocal agreement that renews this partnership through 2025. 3 I INTRODUCTION 4 I HOW ARE SALMON DOING IN OUR WATERSHEDS? 8 I HABITAT RESTORATION: PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES 14 I PROTECTING EXISTING HABITAT IS ALSO CRITICAL FOR FISH 16 I MONITORING EFFORTS TELL US ABOUT THE WATERSHED AND OUR RECOVERY WORK 18 I SUMMER 2015 TEMPERATURE STUDY MAY HOLD LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE 20 I WORKING ON PRIORITIES FOR FISH, FARMS AND FLOODS 22 I SUCCESSES AND FUTURE CHALLENGES 2 SNOQUALMIE WATERSHED FORUM Ten-Year Status Report 2005-2015 Skykomish Snoqualmie The encouraging gains made through restoration are still being outpaced by habitat KING COUNTY loss and degradation throughout Puget Sound. -

An Overview of the Geology and Geomorphology of the Snoqualmie River Watershed

AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE SNOQUALMIE RIVER WATERSHED Prepared by: John Bethel, Geologist Ecological Services Unit Prepared for: Fran Solomon, Ph.D., Senior Ecologist Watershed and Ecological Assessment Team April 2004 Department of Natural Resources and Parks Water and Land Resources Division Capital Projects and Open Space Acquisitions Section 201 South Jackson Street, Suite 600 Seattle, Washington 98104-3855 An Overview of the Geology and Geomorphology of the Snoqualmie River Watershed Prepared by John Bethel, Geologist Ecological Services Unit Prepared for King County Water and Land Resources Division Snoqualmie Watershed Team September 2004 Department of Natural Resources and Parks Water and Land Resources Division Capital Projects and Open Space Acquisitions Section 201 South Jackson Street, Suite 600 Seattle, Washington 98104-3855 King County Executive Ron Sims King County Council Carolyn Edmonds, District 1 Bob Ferguson, District 2 Kathy Lambert, District 3 Larry Phillips, District 4 Dwight Pelz, District 5 Rob McKenna, District 6 Pete von Reichbauer, District 7 Dow Constantine, District 8 Steve Hammond, District 9 Larry Gossett, District 10 Jane Hague, District 11 David Irons, District 12 Julia Patterson, District 13 Department of Natural Resources and Parks Pam Bissonnette, Director Water and Land Resources Division Daryl Grigsby, Division Director Contributing Staff John Bethel, Geologist Supporting Staff Fran Solomon, Ph.D., Senior Ecologist Terry Butler, Geologist Gino Lucchetti, Senior Ecologist Wendy Gable Collins, Graphic Designer and Cartographer Bob Gilland, Technical Information Processing Specialist AN OVERVIEW OF THE GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE SNOQUALMIE RIVER WATERSHED Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction..................................................................................................................1 1.1. Purpose and Scope of this Report .......................................................................1 1.2. -

DRAFT Tolt River Channel Migration Study

DRAFT Tolt River Channel Migration Study March 2017 Prepared by Department of Natural Resources and Parks Water and Land Resources Division River and Floodplain Management Section 201 South Jackson Street, Suite 600 Seattle, WA 98104 Alternate Formats Available 206-477-4800 TTY Relay: 711 DRAFT Tolt River Channel Migration Study March 2017 Submitted by: Terry Butler, Geologist King County Water and Land Resources Division Department of Natural Resources and Parks Funded by: King County Flood Control District DRAFT Tolt River Channel Migration Study Acknowledgements John Bethel, Sevin Bilir, Fred Lott and Kyle Comanor participated in fieldwork during study preparation. Jennifer Vanderhoof provided technical editing of this report. Snoqualmie River Basin Team members Chase Barton and Sally King provided review and comment on a draft of this report. Jeanne Stypula supervised the study and map preparation. Citation King County. 2017. Tolt River channel migration study. Prepared by Terry Butler and Fred Lott. King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks, Water and Land Resources Division. Seattle, Washington. King County River and Floodplain Management i March 2017 DRAFT Tolt River Channel Migration Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... vii 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. -

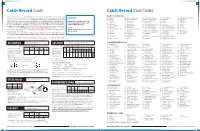

Catch Record Cards & Codes

Catch Record Cards Catch Record Card Codes The Catch Record Card is an important management tool for estimating the recreational catch of PUGET SOUND REGION sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness crab. A catch record card must be REMINDER! 824 Baker River 724 Dakota Creek (Whatcom Co.) 770 McAllister Creek (Thurston Co.) 814 Salt Creek (Clallam Co.) 874 Stillaguamish River, South Fork in your possession to fish for these species. Washington Administrative Code (WAC 220-56-175, WAC 825 Baker Lake 726 Deep Creek (Clallam Co.) 778 Minter Creek (Pierce/Kitsap Co.) 816 Samish River 832 Suiattle River 220-69-236) requires all kept sturgeon, steelhead, salmon, halibut, and Puget Sound Dungeness Return your Catch Record Cards 784 Berry Creek 728 Deschutes River 782 Morse Creek (Clallam Co.) 828 Sauk River 854 Sultan River crab to be recorded on your Catch Record Card, and requires all anglers to return their fish Catch by the date printed on the card 812 Big Quilcene River 732 Dewatto River 786 Nisqually River 818 Sekiu River 878 Tahuya River Record Card by April 30, or for Dungeness crab by the date indicated on the card, even if nothing “With or Without Catch” 748 Big Soos Creek 734 Dosewallips River 794 Nooksack River (below North Fork) 830 Skagit River 856 Tokul Creek is caught or you did not fish. Please use the instruction sheet issued with your card. Please return 708 Burley Creek (Kitsap Co.) 736 Duckabush River 790 Nooksack River, North Fork 834 Skokomish River (Mason Co.) 858 Tolt River Catch Record Cards to: WDFW CRC Unit, PO Box 43142, Olympia WA 98504-3142.