2009 Trial Monitoring Report Azerbaijan N a J I a B R E Z A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 39176 January 2007 Proposed Multitranche Financing Facility Republic of Azerbaijan: Road Network Development Investment Program Tranche I: Southern Road Corridor Improvement Prepared by the Road Transport Service Department for the Asian Development Bank. The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. 2 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 2 January 2007) Currency Unit – Azerbaijan New Manat/s (AZM) AZM1.00 = $1.14 $1.00 = AZM0.87 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DRMU – District Road Maintenance Unit EA – executing agency EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan ESS – Ecology and Safety Sector IEE – initial environmental examination MENR – Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources MFF – multitranche financing facility NOx – nitrogen oxides PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance ROW – right-of-way RRI – Rhein Ruhr International RTSD – Road Transport Service Department SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SOx – sulphur oxides TERA – TERA International Group, Inc. UNESCO – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization WHO – World Health Organization WEIGHTS AND MEASURES C – centigrade m2 – square meter mm – millimeter vpd – vehicles per day CONTENTS MAP I. Introduction 1 II. Description of the Project 3 IIII. Description of the Environment 11 A. Physical Resources 11 B. Ecological and Biological Environment 13 C. -

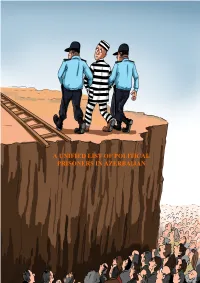

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized

MONGOLIA: Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Acknowledgements This Mongolia Strategic Country Diagnostic was led by Samuel Freije-Rodríguez (lead economist, GPV02) and Tuyen Nguyen (resident representative, IFC Mongolia). The following World Bank Group experts participated in different stages of the production of this diagnostics by providing data, analytical briefs, revisions to several versions of the document, as well as participating in several internal and external seminars: Rabia Ali (senior economist, GED02), Anar Aliyev (corporate governance officer, CESEA), Indra Baatarkhuu (communications associate, EAPEC), Erdene Badarch (operations officer, GSU02), Julie M. Bayking (investment officer, CASPE), Davaadalai Batsuuri (economist, GMTP1), Batmunkh Batbold (senior financial sector specialist, GFCP1), Eileen Burke (senior water resources management specialist, GWA02), Burmaa Chadraaval (investment officer, CM4P4), Yang Chen (urban transport specialist, GTD10), Tungalag Chuluun (senior social protection specialist, GSP02), Badamchimeg Dondog (public sector specialist, GGOEA), Jigjidmaa Dugeree (senior private sector specialist, GMTIP), Bolormaa Enkhbat (WBG analyst, GCCSO), Nicolaus von der Goltz (senior country officer, EACCF), Peter Johansen (senior energy specialist, GEE09), Julian Latimer (senior economist, GMTP1), Ulle Lohmus (senior financial sector specialist, GFCPN), Sitaramachandra Machiraju (senior agribusiness specialist, -

Turkey Into the Abyss? Suna Erdem on Whether Turkey’S Politicians Can Prevent a Catastrophe from Unfolding

Inside this issue: Out of Africa for Russian banking exile Jennings Mattoni puts the fizz into Central European waters Slovakia’s Fico told to take November 2015 www.bne.eu his trousers down GBP 4.50/USD 6.75/EUR 5.90 Turkey into the abyss? Suna Erdem on whether Turkey’s politicians can prevent a catastrophe from unfolding Special Report: Ben Aris looks at Georgian PM CEE/CIS Bank Moscow Exchange’s Garibashvili Survey 2015 revival p. 12 talks China, p. 28 Russia and trade p. 60 ISSN 2059-2736 ISSN bne November 2015 Contents I 3 Senior editorial board Ben Aris (Moscow) +7 9162903400 editor-in-chief [email protected] 20 10 James R Hammond (Boston) +1 6178525441 publisher [email protected] Nicholas Watson (Prague) +42 0731582719 managing editor [email protected] Robert Anderson (Prague) +42 0603517867 news editor [email protected] Liam Halligan (London) +44 7801799279 editor-at-large [email protected] Central Asia 15 Naubet Bisenov (Almaty) +7 7015933810 bureau chief [email protected] Eastern Europe 6 THE MONTH THAT WAS 28 SPECIAL REPORT – Nicholas Allen (Berlin) +49 15730395872 CEE/CIS Bank Survey 2015 bureau chief [email protected] Central Europe COMPANIES & MARKETS Tim Gosling (Prague) +42 0720180811 36 COVER FEATURE bureau chief [email protected] 10 Out of Africa for Russia Southeast Europe banking exile Jennings Turkey into the abyss? Clare Nuttall (Bucharest) +7 7073011495 bureau chief [email protected] 11 Russia’s central bank limits foreign shareholder voting Advertising & subscription CENTRAL EUROPE Elena Arbuzova (Moscow) +7 9160015510 business -

The Election Process of the Regional Representatives to the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan

№ 20 ♦ УДК 342 DOI https://doi.org/10.32782/2663-6170/2020.20.7 THE ELECTION PROCESS OF THE REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES TO THE PARLIAMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ВИБОРЧИЙ ПРОЦЕС РЕГІОНАЛЬНИХ ПРЕДСТАВНИКІВ У ПАРЛАМЕНТ АЗЕРБАЙДЖАНСЬКОЇ ДЕМОКРАТИЧНОЇ РЕСПУБЛІКИ Malikli Nurlana, PhD Student of the Lankaran State University The mine goal of this article is to investigate the history of the creation of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan par- liament, laws on parliamentary elections, and the regional election process in parliament. In addition, an analysis of the law on elections to the Azerbaijan Assembly of Enterprises. The article covers the periods of 1918–1920. The presented article analyzes historical processes, carefully studied and studied the process of elections of regional representatives to the Parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan. Realities are reflected in an objective approach. A comparative historical study of the election of regional representatives was carried out in the context of the creation of the parliament of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan and the holding of parliamentary elections. The scientific novelty of the article is to summarize the actions of the parliament of the first democratic republic of the Muslim East. Here, attention is drawn to the fact that before the formation of the parliament, the National Assembly, in which the highest executive power, trans- ferred its powers to the legislative body and announced the termination of its activities. It is noted that the Declaration of Independence of Azerbaijan made the Republic of Azerbaijan a democratic state. It is from this point of view that attention is drawn to the fact that the government of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic had to complete the formation of institutions capable of creating a solid legislative base in a short time. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD1591 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT PAPER FOR AN Public Disclosure Authorized ADDITIONAL LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$66.7 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN FOR THE IDP LIVING STANDARDS AND LIVELIHOODS PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized June 17, 2016 Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice Europe and Central Asia Region This document is being made publicly available prior to Board consideration. This does not imply a presumed outcome. This document may be updated following Board consideration and the updated document will be made publicly available in accordance with the Bank’s policy on Access to Information. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective May 20, 2016) Currency Unit = New Azerbaijani Manat (AZN) AZN 1.49 = US$1 US$0.71 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AF Additional Financing CPF Country Partnership Framework ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework FM Financial Management GoA Government of Azerbaijan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism GRS Grievance Redress Service IDP Internally Displaced Person IFR Interim Financial Report O&M Operations and Maintenance OM Operational Manual PDO Project Development Objective PIU Project Implementation Unit RAP Resettlement Action Plan RPF Resettlement Policy Framework SFDI Social Fund for the Development of IDPs Vice President: Cyril E Muller Country Director: Mercy Miyang Tembon Senior Global Practice Director: Ede Jorge Ijjasz-Vasquez Country Manager: Larisa Leshchenko Practice Manager: Nina Bhatt Task Team Leader: Michelle P. Rebosio Calderon REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN ADDITIONAL FINANCING TO IDP LIVING STANDARDS AND LIVELIHOODS PROJECT (P155110) CONTENTS Project Paper Data Sheet i Project Paper I. -

Oil and the Search for Peace in the South Caucasus: the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) Oil Pipeline

Oil and the Search for Peace in the South Caucasus: The Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline December 2004 Acknowledgements The following research document is a result of 18 months intensive work of International Alert’s Business & Conflict – BTC Research project team: Adam Barbolet, Davin Bremner, Phil Champain, Rachel Goldwyn, Nick Killick, Diana Klein. The team would also like to thank many other Alert staff past and present, as well as the following regional experts who significantly contributed to the project. Burcu Gultekin Ashot Khurshudyan Razi Nurullayev Zviad Shkvitaridze Arif Yunusov Staff of Himayadar- Oil Information & Resource Centre in Baku The project team is grateful to the UK government’s Global Conflict Prevention Pool (GCPP) for its generous financial support. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................ 2 Acronyms........................................................................................................................................ 5 Executive summary........................................................................................................................ 7 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 24 1.1 The contribution of the oil industry to conflict prevention – emerging conflict-sensitive management systems ............................................................................................................... -

Official Transcript.Pdf

HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN AZERBAIJAN HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 29, 2008 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 110–2–19] ( Available via http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 63–897 PDF WASHINGTON : 2013 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:13 Jan 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\WORK\072908.TXT KATIE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida, BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland, Chairman Co-Chairman LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin New York CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut MIKE McINTYRE, North Carolina HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York HILDA L. SOLIS, California JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts G.K. BUTTERFIELD, North Carolina SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GORDON SMITH, Oregon ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania RICHARD BURR, North Carolina MIKE PENCE, Indiana EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS DAVID J. KRAMER, Department of State MARY BETH LONG, Department of Defense DAVID BOHIGIAN, Department of Commerce (II) VerDate 0ct 09 2002 13:13 Jan 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\WORK\072908.TXT KATIE HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATIZATION IN AZERBAIJAN JULY 29, 2008 COMMISSIONERS Page Hon. -

Human Rights Impact Assessment of the State Response to Covid-19 in Azerbaijan

HUMAN RIGHTS IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE STATE RESPONSE TO COVID-19 IN AZERBAIJAN July 2020 Cover photo: Gill M L/ CC BY-SA 2.0/ https://flic.kr/p/oSZ9BF IPHR - International Partnership for Human Rights (Belgium) W IPHRonline.org @IPHR E [email protected] @IPHRonline BHRC - Baku Human Rights Club W https://www.humanrightsclub.net/ Bakı İnsan Hüquqları Klubu/Baku Human Rights Club Table of Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 5 BRIEF COUNTRY INFORMATION 5 Methodology 6 COVID 19 in Azerbaijan and the State’s response 7 NORMATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE PANDEMIC AND RESTRICTIVE MEASURES 7 ‘SPECIAL QUARANTINE REGIME’ 8 ‘TIGHTENED QUARANTINE REGIME’ 9 ADMINISTRATIVE AND CRIMINAL LIABILITY FOR FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH QUARANTINE RULES 10 Impact on human rights 11 IMPACT ON A RIGHT TO LIBERTY 12 IMPACT ON PROHIBITION OF ILL-TREATMENT: DISPROPORTIONATE POLICE VIOLENCE AGAINST ORDINARY CITIZENS 14 IMPACT ON FAIR TRIAL GUARANTEES 15 IMPACT ON A RIGHT TO PRIVACY 15 IMPACT ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND A RIGHT TO IMPART INFORMATION 16 IMPACT ON FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY 18 IMPACT ON HEALTH CARE AND HEALTH WORKERS 19 IMPACT ON PROPERTY AND HOUSING 20 IMPACT ON SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RIGHTS 20 IMPACT ON A RIGHT TO EDUCATION 21 IMPACT ON MOST VULNERABLE GROUPS 21 Recommendations to the government of Azerbaijan 25 Executive summary As the world has been struct by the COVID-19 outbreak, posing serious threat to public health, states resort to various extensive unprecedented measures, which beg for their assessment through the human rights perspective. This report, prepared by the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) and Baku Human Rights Club (BHRC), examines the measures taken by Azerbaijan and the impact that it has on human rights of the Azerbaijani population, including those most vulnerable during the pandemic. -

Severe Torture and Unfair Trials of Members of the Nardaran Community

Azerbaijan: Severe Torture and Unfair Trials of Members of the Nardaran Community The World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), requests your urgent intervention in the following situation in Azerbaijan. Description of the situation: The OMCT has been informed by reliable sources about severe torture and unfair trials in the cases of 18 members of the Shiite minority of Nardaran including Mr. Taleh Bagirzadeh, Mr. Jahad Balakishiev, Mr. Shamil Abdylaliev, and Mr. Bahruz Askerov. They were arrested on 26 November 2015 during a special operation of the Main Directorate for Combating Organized Crime in Nardaran in an attempt to crack down the Muslim Unity, a Shiite organisation that presents an Islamist alternative to the State. In this so-called “Nardaran case”, the arrested are charged with serious crimes including murder, terrorism, riots, illegal possession of weapons, violent seizure of power, incitement to religious hatred. According to information received by his lawyer, Mr Taleh Bagirzadeh the head of Muslim Unity, was arrested and was brought to a van where officers proceeded in hitting his face, smashing his head on the ground, trying to break his back and verbally abusing him. Mr. Bagirzadeh was subsequently brought to the offices of the Main Organized Crime Department where he was forced to lay on the ground and was severely beaten resulting in blood loss and open flesh wounds. Two to three days after his arrest, an investigator from the General Prosecutor’s office visited Mr. Bagirzadeh and expressed shock about his condition. However, no investigation was initiated. During his arbitrary detention on the premises of the Organized Crime Department, Mr. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle .............................................................................................................................................