Empirical Estimation of Exchange Rate Movements in the New Zealand Dollar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu

Global Wire is an available payment method for the currencies listed below. This list is subject to change at any time. Currency Codes COP Colombian Peso KWD Kuwaiti Dinar RON Romanian Leu ALL Albanian Lek KMF Comoros Franc KGS Kyrgyzstan Som RUB Russian Ruble DZD Algerian Dinar CDF Congolese Franc LAK Laos Kip RWF Rwandan Franc AMD Armenian Dram CRC Costa Rican Colon LSL Lesotho Malati WST Samoan Tala AOA Angola Kwanza HRK Croatian Kuna LBP Lebanese Pound STD Sao Tomean Dobra AUD Australian Dollar CZK Czech Koruna LT L Lithuanian Litas SAR Saudi Riyal AWG Arubian Florin DKK Danish Krone MKD Macedonia Denar RSD Serbian Dinar AZN Azerbaijan Manat DJF Djibouti Franc MOP Macau Pataca SCR Seychelles Rupee BSD Bahamian Dollar DOP Dominican Peso MGA Madagascar Ariary SLL Sierra Leonean Leone BHD Bahraini Dinar XCD Eastern Caribbean Dollar MWK Malawi Kwacha SGD Singapore Dollar BDT Bangladesh Taka EGP Egyptian Pound MVR Maldives Rufi yaa SBD Solomon Islands Dollar BBD Barbados Dollar EUR EMU Euro MRO Mauritanian Olguiya ZAR South African Rand BYR Belarus Ruble ERN Eritrea Nakfa MUR Mauritius Rupee SRD Suriname Dollar BZD Belize Dollar ETB Ethiopia Birr MXN Mexican Peso SEK Swedish Krona BMD Bermudian Dollar FJD Fiji Dollar MDL Maldavian Lieu SZL Swaziland Lilangeni BTN Bhutan Ngultram GMD Gambian Dalasi MNT Mongolian Tugrik CHF Swiss Franc BOB Bolivian Boliviano GEL Georgian Lari MAD Moroccan Dirham LKR Sri Lankan Rupee BAM Bosnia & Herzagovina GHS Ghanian Cedi MZN Mozambique Metical TWD Taiwan New Dollar BWP Botswana Pula GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal -

View Currency List

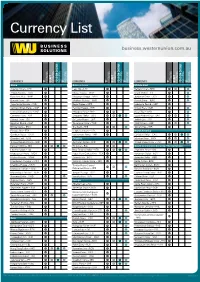

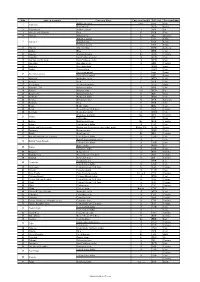

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

May 5, 2006 Technical Revisions to the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement

May 5, 2006 Technical revisions to the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement The Foreign Exchange Committee (FXC), International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. (ISDA), and EMTA, Inc. announce two technical revisions to the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions (“2005 Supplement”). The first revision suggests how to incorporate into a Barrier or Binary Option Transaction the terms of the 2005 Supplement. The relevant Confirmation of the Barrier or Binary Option Transaction should state that “the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended by the 2005 Barrier Option Supplement, as published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc., EMTA, Inc., and the Foreign Exchange Committee are incorporated into this Confirmation.” For purposes of clarity, this provision has been added to Exhibits I and II to the 2005 Supplement, which illustrate how Barrier and Binary Options may be confirmed under the terms of the 2005 Supplement and the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions (“1998 Definitions”) (see the second paragraph and footnote 2 of each Exhibit). The revised Exhibits I and II are attached to this announcement. The second revision further describes the approach taken to the conventions for stating Currency Pairs in the Currency Pair Matrix that was published with the 2005 Supplement. The Matrix is provided as a best practice to facilitate the use of standard market convention when specifying the exchange rates relating to certain terms in a Confirmation of a Barrier or Binary Option Transaction that incorporates the provisions of the 2005 Supplement. The introductory statement to the Matrix has been revised to highlight that its conventions for stating currency pairs may be different from trading conventions. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

Rupee Rises 21 Paise to Hit a Month High of 70.92

Rupee rises 21 paise to hit a month high of 70.92 “the hope of US-China deal, risk of trade war seems to be unwinding, because of which the Asian currencies have been gaining.” : MV Srinivasan, VP, Mecklai Financial Services to Financial Express The rupee was earlier trading at a six paise premium on the non-deliverable forward (NDF) market. he rupee on Friday rose 21 paise to close at a month high of 70.92 against the dollar on the back of appreciation in Asian currencies, especially in the Chinese yuan, on hope of trade talk between the US and China. The weakening Dollar Index also seemed to be contributing to the appreciation of rupee. After touching a three-year high of 99 on September 03, 2019, the Dollar Index fell to 98.14 on Friday. As a result, most of the Asian currencies appreciated against the dollar. In the last five trading sessions, the Thai baht rose 0.56%, the Malaysian ringgit rose 0.33%, the South Korean won rose 1.71%, the Indian rupee rose 1.12%, the Indonesian rupiah rose 0.96% and the Chinese renminbi rose 0.53% against the greenback. MV Srinivasan, vice-president at Mecklai Financial, said that on the hope of US-China deal, risk of trade war seems to be unwinding, because of which the Asian currencies have been gaining. “As the rupee has been following the movement in the Chinese yuan lately, the rising yuan is believed to have influenced the Indian currency,” he added. However, Sajal Gupta, head–forex, Edelweiss Securities, believes that the appreciation in the domestic currency to last only for a short duration. -

Indonesia - Indonesian Rupiah, Idr

As of March 16th 2015 INDONESIA - INDONESIAN RUPIAH, IDR Country: Indonesia Currency: Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) Phonetic Spelling: {ru: ‘pi: ah} Country Overview Abbreviation: IDR FOREIGN EXCHANGE Controlled by Bank Indonesia (Bank Sentral Repulik Indonesia), the Indonesian Etymology rupiah has been one of the best-performing emerging market currencies year-to-date The origin of the word rupiah can be traced back to the in relation to the USD. The IDR’s 20% depreciation last year prompted the regulators Hindi word rūpiya, which itself is derived from the Sanskrit to intervene in the currency market, and to implement certain measures so as to word rūpya, meaning, “wrought silver, a coin of silver”. reduce the pressure on the country’s economic benchmarks, such as curbing imports Indonesians also use the colloquial word “perak” (which and tightening monetary policy. And as the rupiah has steadily rebounded, the central means ‘silver’ in Indonesian) when referring to rupiah. bank has been able to rebuild its foreign exchange reserves, creating a period of Currency History relative stability. The rupiah has a long history that stretches back to colonial period. During the period where Indonesia was SOVEREIGN DEBT a Dutch colony, the country used the Netherlands Indies The market’s perception of Indonesia’s sovereign credit risk has been rather volatile Guilden as the national currency up until the Japanese recently, however, the IMF forecasts a further moderate decline in public debt due to invasion in 1942. The Japanese printed their own version currency appreciation, falling interest rates, and planned economic growth. Future of the Guilden, which continued to act as the currency energy subsidy reduction and tax reforms, in combination with stronger economic even after the war, although its supply dwindled due to the destruction of printing plates. -

Payment Information and Terms 2018 Revised April 2018.Pages

" Payment terms: 2.500.000,- Rp per room at the time of reservation and 45 days before arrival either. This is possible on a bank in the Netherlands in Euro or an Indonesian bank in Rupiah. In case of bank transfers, the transfer costs are for the transferring party. Please contact us for details at mailto:[email protected] It is also possible to pay the advanced payment with credit card, Visa and Master. If you choose for this option we send you an invoice by email with a secure link. From there you follow the instructions. There are no extra costs from our side for this option. Cancellations policy: In principal, deposits paid in advance, are non-refundable. However, depending on the reason of cancellation, they can remain valid until a later date. Paying options in the resort: In the resort and at the end of your stay, you will receive the invoice in Rupiah. This can be paid with cash Indonesian Rp and Euro. Also with credit card, Master and Visa (PIN required in case your card comes with one). Payments by credit card in Indonesia are by law only accepeted in Rupiah so no currency conversions are necessary. We do not charge extra for credit card payments in the resort. An alternative is an internet payment to either our European account in Euro, or our Indonesian account in Rupiah. For that you probably have to have your login information standby. In case of bank transfers, the transfer costs are for the transferring party. For exchange rate conversions we use the currency calculator as standing on the bottom of the prices page of our web site: www.lumbalumbadiving.com Why are our prices in Rupiah? Our prices changed from Euro to Indonesian Rupiah to comply with a new law that all companies have to quote their products in Indonesian Rupiah (IDR or Rp). -

Mizuho Dealer's

Mizuho Dealer’s Eye August 2018 U.S. Dollar .................................................................... 1 Chinese Yuan ............................................................. 19 Euro .............................................................................. 4 Singapore Dollar ........................................................ 22 British Pound ................................................................ 7 Thai Baht .................................................................... 25 Australian Dollar .......................................................... 9 Malaysian Ringgit ...................................................... 28 Canadian Dollar ......................................................... 11 Indonesian Rupiah ..................................................... 31 Korean Won ............................................................... 13 Philippine Peso ........................................................... 33 New Taiwan Dollar .................................................... 15 Indian Rupee .............................................................. 36 Hong Kong Dollar ..................................................... 17 Mizuho Bank, Ltd. Forex Department Mizuho Bank | Mizuho Dealer’s Eye Tomokazu Moriya, Forex Sales, Forex Department U.S. Dollar – August 2018 Expected Ranges Against the yen: JPY109.00–113.00 1. Review of the Previous Month The dollar/yen pair strengthened in July. After opening the month trading at the upper-110 yen mark on July 2, the pair then topped -

TR SEF: NDF Product Listing

Thomson Reuters (SEF) LLC 3 Times Square New York, NY 10036 March 24, 2017 VIA ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION Commodity Futures Trading Commission Three Lafayette Centre 1155 21st Street, NW Washington, DC 20581 Re: New Contract Submission 17-02.29: Rule 40.2(a) Certification of Thomson Reuters (SEF) LLC Cross-Currency Non-Deliverable Forwards Ladies and Gentlemen: Thomson Reuters (SEF) LLC (“TR SEF”) hereby notifies the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”), pursuant to CFTC Regulation 40.2(a), that it is certifying 43 Cross- Currency Non-Deliverable Forward contracts (the “Contracts”) on TR SEF’s swap execution facility platform. TR SEF’s intended listing date is April 3, 2017. Specifically, TR SEF certifies Cross-Currency NDFs in the following currencies: Deliverable Currencies Non-Deliverable Currencies AED United Arab Emirates Dirham ARS Argentine Peso AUD Australia Dollar BRL Brazilian Real BGN Bulgaria Lev CLP Chilean Peso BWP Botswana Pula CNY Chinese Renminbi CAD Canada Dollar COP Colombian Peso CHF Switzerland Franc EGP Egyptian Pound CNH Offshore Chinese Renminbi GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal CZK Czech Republic Koruna IDR Indonesian Rupiah DKK Denmark Krone INR Indian Rupee EEK Estonia Kroon KES Kenya Shilling EUR Euros KRW South Korean Won GBP United Kingdom Pound KZT Kazakh Tenge HKD Hong Kong Dollar MYR Malaysian Ringgit HRK Croatia Kuna PEN Peruvian Nuevo Sol HUF Hungary Forint PHP Philippine Peso ILS Israel Shekel PKR Pakistan Rupee ISK Iceland Krona RUB Russian Ruble JMD Jamaica Dollar THB Thai Baht JOD Jordan Dinar TWD Taiwan Dollar JPY Japan Yen UAH Ukrainian Hryvnia KWD Kuwait Dinar UYU Uruguayan Peso LKR Sri Lanka Rupee VEF Venezuelan Bolívar LVL Latvia Lats VND Vietnamese Dong MAS Morocco Dirham MUR Mauritius Rupee MXN Mexico Peso NOK Norway Krone NZD New Zealand Dollar OMR Oman Rial PLN Poland Zloty QAR Qatar Riyal RON Romania New Leu RSD Serbia Dollar SAR Saudi Arabia Riyal SEK Sweden Krona SGD Singapore Dollar SKK Slovakia Koruna TND Tunisia Dollar TRY Turkey Lira USD U.S. -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Explaining the New Currency of East Timor

Where can I change money and who determines the exchange rate? Banks and foreign exchange bureaus will provide money changing services. EXPLAINING THE The exchange rate will be determined by these institutions on the basis of supply and demand for the respective currencies. NEW CURRENCY The exchange rate may vary from one place to another. OF EAST TIMOR The Central Payments Office (CPO) will publish daily selected indicative exchange rates taken from the international financial markets. These rates will show how much the rupiah, Australian dollar, escudo, baht and Euro are worth against the US$. These rates will be posted daily in banks, airports, exchange bureaus and other public places. Questions and Will there be rules for businesses that exchange money? Yes. The CPO will license and supervise financial institutions, Answers about including currency exchange bureaus (cambio). Will East Timor have its own currency in the future and using the what will it be? The people and government of East Timor may eventually choose united states to establish their own currency, with whatever design and name. united states Until that time, the US$ will remain the legal tender. dollar (us$) UNTAET/OCPI UNITED NATIONS TRANSITIONAL ADMINISTRATION IN EAST TIMOR IC/02E 5,000 Feb 2000 Who will control prices? By Regulation 2000/7 of 24 January 2000, the United Prices will be determined through the principle of supply and demand, States dollar (US$) became the new legal tender in East and not by any government agency. Timor. This means that all official transactions must be carried out in US$. For example, payments of your For example, the price of bananas may rise if many people want to buy them (demand), but there are not enough bananas (supply).